A Strategy for Public Open Space in Middlesbrough 2007-2012

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Supporting Your Local Businesses Our Valued Customers Provide Essential and Well-Used Services for Us All in the Heart of Our Communities

Supporting your local businesses Our valued customers provide essential and well-used services for us all in the heart of our communities. From small businesses such as hairdressers and bakeries to pharmacies and newsagents. We know that every one of them works incredibly hard to run a successful business, which they’re very proud of, and we can all play a part to help them maintain their success. Each business is unique and their success is so important to us. By supporting local businesses, you’re not only helping to support local entrepreneurs, you’re helping to make a valued contribution to the local economy. Contents Middlesbrough 3-4 Hartlepool 5-7 Stockton 7-9 East Cleveland 9 North Yorkshire 9 2 Middlesbrough Food and Hospitality Pete’s Pantry - Sandwich Shop DJ’s Pizzeria - Takeaway 28 Rothbury Road 43 Marshall Avenue Berwick Hills Brambles Farm Middlesbrough Middlesbrough TS3 7NW TS3 9AX 01642 244910 The Coffee Bean 23 Shelton Court Popin Pizza - Takeaway Thorntree 19 Shelton Court Middlesbrough Thorntree Piccos Pizza TS3 9PD Middlesbrough Hot Food Takeaway TS3 9PD 32 Rothbury Road Park Plaice Fish & Chips 01642 222324 Berwick Hills 265 Cargo Fleet Lane Middlesbrough Cargo Fleet Food-U-Like - Fish and Chip TS3 7NW Middlesbrough Shop 01642 211666 TS3 8EX 38 Broughton Avenue 01642 251808 Easterside Parkend Pizzeria - Takeaway Middlesbrough 8 Bourton Court TS4 3PZ Park End Middlesbrough TS3 7DT 01642 913940 Hair and Beauty Teasdale Academy of Egyptian Sun Tanning Salon Hair & Beauty 17 The Gardens 5 Shelton Court Beechwood Thorntree -

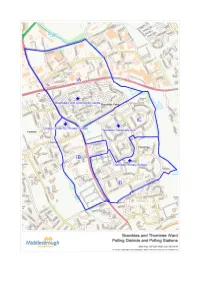

Middlesbrough Ward: Brambles and Thorntree Polling District: IA

Electoral Division: Middlesbrough Parliamentary Constituency: Middlesbrough Ward: Brambles and Thorntree Polling District: IA POLLING STATION LOCATION: Brambles Farm Community Centre, Marshall Avenue, TS3 9AY TOTAL ELECTORS: 1888 TURNOUT: Combination of 2 existing stations, so no direct comparison. STREETS COVERED (See attached map): Cargo Fleet Lane, Falcon Road, Hawk Road, Kestrel Avenue, Longlands Road, Merlin Road, Alexander Terrace, Aston Avenue, Barrass Grove, Berwick Hills Avenue, Burnholme Avenue, Cherwell Terrace, College Road, Cranfield Avenue, Ferndale Avenue, Ferndale Court, Grimwood Avenue, Hanson Grove, Hatherley Court, Hopkins Avenue, Ings Avenue, Kedward Avenue, Lilac Grove, Lowfield Avenue, Marshall Avenue, Marshall Court, Matford Avenue, Millbrook Avenue, Northfleet Avenue, Pallister Avenue, Pallister Court, Thorntree Avenue, Tomlinson Way, Turford Avenue, Villa Road, Weston Avenue, Winslade Avenue. ELECTORAL OFFICERS COMMENTS: Location & suitability Existing station familiar to residents. Centrally located within the residential area of the polling district. The previous mobile station on Cargo Fleet Lane has been combined into this station as this served a very small number of electors (283). Mobile stations cost approximately 3 times the cost of a station located within a public building. Parking Nearby on street parking Access Fully accessible Facilities for staff Satisfactory Recommendation Most suitable building within polling district. RETURNING OFFICERS COMMENTS: This polling station has been used for several -

Community Stepping Stones Games Afternoon 21

1 On Sunday 17th March, Age UK Teesside held our first Zumbathon to fight loneliness in Teesside. Instructor Glyn Stinchcombe (below, right) developed the routine with his Zumba class, members of which took part on the day, and led the group for a 2-hour dance through time. Everyone who took part did an amazing job and helped raise money to reduce loneliness and isolation in our community. Thank you to our instructor Glyn, all of the dancers and everyone who sponsored them for supporting your local Age UK and enabling us to support local older people. (More photographs on page 3) 2 Zumbathon 3 Meet: Ellie Lowther 4 Bungee Jump 2019 5 Strollers & Straggler 6-7 Fundraising 8 Bark in the Park (Summer) 9 Lasting Power of Attorney 10 Music in Hospitals: Pop-Up Cafes 11 Dementia Cafes 12 BHBW Group Schedule 13 Phoenix Group Schedule 14-15 Phoenix Easter Bonnet Competition 16 Phoenix Friendship Friday 17 Phoenix Lunch & Social 18 The Big Knit 18-19 Redcar Extended Service 20 Community Stepping Stones Games Afternoon 21 Redcar Befriending Service 22-23 Befriending Roadshow 24 Middlesbrough Befriending Service 25 Hartlepool Befriending Network 26 Puffin Group 27 Peer Support Groups 28 Information Event 29 Community Hub Advice Service 30 Useful Information 31 3 Zumbathon (continued) Whilst our fundraisers danced away, staff showed their support and snapped the following photographs. Thank you once again to everyone involved and brought such wonderful energy on the day. 4 Ellie Lowther Age UK Teesside are delighted to welcome Ellie Lowther, founder of Trans Aware & Essential Learning Curve Ltd as our new Equality and Diversity Officer. -

Community Conversations: the Responses

Community Conversations: The Responses August 2018 Hannah Roderick Middlesbrough Voluntary Development Agency Community Conversations March - July 2018 Contents Introduction 1 Who responded? 2 How did they respond? 6 Question one 7 What is life like in Middlesbrough for you and your family? Question two 11 What could be done to improve life in Middlesbrough For you, your family and others around you Question three 19 What could your role in that be? Question four 22 What would help you to do this? Question five 25 How would we know that things were improving for people in Middlesbrough? Next steps 30 2 Community Conversations March - July 2018 Introduction This report brings together the initial analysis of the responses from the Middlesbrough Community Conversations, that were hosted between March - July 2018. Volunteers or staff members from 42 different voluntary and community organisations (VCOs) asked people in their communities to answer five questions: 1. What is life like in Middlesbrough for you and your family? 2. What could be done to improve life in Middlesbrough For you, your family and others around you 3. What could your role in that be? 4. What would help you to do this? 5. How would we know that things were improving for people in Middlesbrough? 3 Community Conversations March - July 2018 Who responded? In the period March to June, the 42 VCOs spoke to 1765 people, from across all the Middlesbrough postcode areas. From May to July, members of the public, Councillors and Middlesbrough Council employees were also invited to host conversations. This resulted in a further 110 responses. -

Middlesbrough Boundary Special Protection Area Potential Special

Middlesbrough Green and Blue Infrastructure Strategy Middlesbrough Council Middlesbrough Cargo Fleet Stockton-on-Tees Newport North Ormesby Brambles Farm Grove Hill Pallister Thorntree Town Farm Marton Grove Berwick Hills Linthorpe Whinney Banks Beechwood Ormesby Park End Easterside Redcar and Acklam Cleveland Marton Brookfield Nunthorpe Hemlington Coulby Newham Stainton Thornton Hambleton 0 1 2 F km Map scale 1:40,000 @ A3 Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright and database right 2020 CB:KC EB:Chamberlain_K LUC 11038_001_FIG_2_2_r0_A3P 08/06/2020 Source: OS, NE, MC Figure 2.2: Biodiversity assets in and around Middlesbrough Middlesbrough boundary Local Nature Reserve Special Protection Area Watercourse Potential Special Protection Area Priority Habitat Inventory Site of Special Scientific Interest Deciduous woodland Ramsar Mudflats Proposed Ramsar No main habitat but additional habitats present Ancient woodland Traditional orchard Local Wildlife Site Middlesbrough Green and Blue Infrastructure Strategy Middlesbrough Council Middlesbrough Cargo Fleet Stockton-on-Tees Newport North Ormesby Brambles Farm Grove Hill Pallister Thorntree Town Farm Marton Grove Berwick Hills Linthorpe Whinney Banks Beechwood Ormesby Park End Easterside Redcar and Acklam Cleveland Marton Brookfield Nunthorpe Hemlington Coulby Newham Stainton Thornton Hambleton 0 1 2 F km Map scale 1:40,000 @ A3 Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright and database right 2020 CB:KC EB:Chamberlain_K LUC 11038_001_FIG_2_3_r0_A3P 29/06/2020 Source: OS, NE, EA, MC Figure 2.3: Ecological Connection Opportunities in Middlesbrough Middlesbrough boundary Working With Natural Processes - WWNP (Environment Agency) Watercourse Riparian woodland potential Habitat Networks - Combined Habitats (Natural England) Floodplain woodland potential Network Enhancement Zone 1 Floodplain reconnection potential Network Enhancement Zone 2 Network Expansion Zone. -

Middlesbrough Bus Station

No Public Services Until 2200 Only: 10, 13, 13A, 13B, 14 Longlands, Linthorpe, Tollesby, West Lane Hospital, James Cook University Hospital, Easterside, Marton Manor, Acklam, Until 2200 Only: 39 Trimdon Avenue, Brookfield, Stainton, Hemlington, Coulby Newham North Ormesby, Berwick Hills, Park End Until 2200 Only: 12 Until 2200 Only: 62, 64, 64A, 64B Linthorpe, Acklam, Hemlington, Coulby Newham North Ormesby, Brambles Farm, South Bank, Low Grange Farm, Teesville, Normanby, Bankfields, Eston, Grangetown, Dormanstown, Lakes Estate, Redcar, Ings Farm, New Marske, Marske No Public Services Until 2200 Only: X3, X3A, X4, X4A Until 2200 Only: 36, 37, 38 Dormanstown, Coatham, Redcar, The Ings, Marske, Saltburn, Skelton, Newport, Thornaby Station, Stockton, Norton Road, Norton Grange, Boosbeck, Lingdale, North Skelton, Brotton, Loftus, Easington, Norton, Norton Glebe, Roseworth, University Hospital of North Tees, Staithes, Hinderwell, Runswick Bay, Sandsend, Whitby Billingham, Greatham, Owton Manor, Rift House, Hartlepool No Public Services Until 2200 Only: X66, X67 Thornaby Station, Stockton, Oxbridge, Hartburn, Lingfield Point, Great Burdon, Whinfield, Harrowgate Hill, Darlington, (Cockerton, Until 2200 Only: 28, 28A, 29 Faverdale) Linthorpe, Saltersgill, Longlands, James Cook University Hospital, Easterside, Marton Manor, Marton, Nunthorpe, Guisborough, X12 Charltons, Boosbeck, Lingdale, Great Ayton, Stokesley Teesside Park, Teesdale, Thornaby Station, Stockton, Durham Road, Sedgefield, Coxhoe, Bowburn, Durham, Chester-le-Street, Birtley, Until -

Operation Box Clever Cleveland Police

OPERATION BOX CLEVER CLEVELAND POLICE LANGBAURGH DISTRICT CONTACT OFFICER SGT 1248 Dave Lister Management Support Dawson House Ridley Street Redcar Cleveland TS101TT Tel. (01642) 302008 Fax. (01642) 302725 E-mail [email protected] TILLEY AWARD 2000, SUBMISSION SUMMARY PROJECTTITLE- OPERATION BOX CLEVER The Crime and Disorder Audit for the Redcar and Cleveland Borough Council and Langbaurgh District Police identified the alarming fact that the district of Redcar and Cleveland had the highest levels of arson and hoax calls within the U.K. The two adjacent wards of South Bank and Grangetown were the worst affected, and could justifiably be recognised as "the arson capital of the U.K." The Fire Brigade provided evidence of the twenty-five worst performing enumeration districts across the Cleveland area, ten of these were in the South Bank and Grangetown area. Research by the Fire Brigade identified young hoax callers, if unchallenged, can encourage others to make calls. Some hoax callers will progress to fire play and ultimately fire setting. It was further identified that areas with significant social deprivation also had the highest levels of hoax calls and arson. The Fire Brigade had access to a `one to one education service for referred fire-setters, which had a proven success rate in breaking the offending cycle. Historically, the dispatching of Police resources has always been prioritised. Hoax calls made predominantly by children below the age of criminal responsibility were never afforded the necessary commitment or investigative process and very few were identified. The response to the problem would include arson and hoax calls as a priority within the Community Safety Strategy for the district. -

NE Connected No.1

connected.co.uk ne #1 | may/june 2016 New Construction Firm Lands First Major Contract CAIRN HOTEL HARNESSES GLOBAL TALENT Westray Expands After New Contract Win LEIGH DAY FORMS STRATEGIC IT PARTNERSHIP #NorthEastHeroes ACADEMICS PREPARING SELF-HEALING CONCRETE Tour de Yorkshire 2016 HILL CARE SUPPORTS 120-MILE CHARITY CYCLE RIDE Pilot schools share over £50,000 WORKING WITH YOU, FOR YOU Father and daughter team up at family dealership DARLINGTON BUSINESSMAN IS GOING NOWHERE SUPERFAST Boro Taxis makes airport fares pledge EXPERTISE YOUNG CYSTIC FIBROSIS SUFFERERS Businesses Hold Future of Stockton in Their Hands SUPPORTED LIVING SCHEME CELEBRATES FIRST ANNIVERSARY Acklam Hall welcomes extra special VIP visitor welcome contents Construction neconnected.co.uk 3 New Construction Firm Lands First Major Contract North East Connected is a news Our aim with North East Business portal created to announce all the Connected is two-fold, great things that are happening in 4 Cairn Hotel Newcastle Continues To Harness Global Talent • To provide North East the North East. We are fiercely 5 Westray Expands After New Contract Win businesses with a medium to proud of our heritage and our Digital share their successes, promote region, with so much to shout 6 Leigh Day forms strategic IT partnership to support growth their company and talk about about, we are a medium to get great news. Social Media those positive stories out there 7 #NorthEastHeroes and a forum to share the good • And to make people living Education and the great. outside of our region aware of 8 Teesside University academics preparing self-healing concrete all the great opportunities Sport within the North East. -

Literacy and Life Expectancy

A National Literacy Trust research report Literacy and life expectancy An evidence review exploring the link between literacy and life expectancy in England through health and socioeconomic factors Lisa Gilbert, Anne Teravainen, Christina Clark and Sophia Shaw February 2018 All text © The National Literacy Trust 2018 T: 020 7587 1842 W: www.literacytrust.org.uk Twitter: @Literacy_Trust Facebook: nationalliteracytrust The National Literacy Trust is a registered charity no. 1116260 and a company limited by guarantee no. 5836486 registered in England and Wales and a registered charity in Scotland no. SC042944. Registered address: 68 South Lambeth Road, London SW8 1RL Table of contents Introduction............................................................................................................................ 3 Summary of key findings ........................................................................................................ 4 Literacy and life expectancy in England ................................................................................. 6 Exploring the link between literacy and life expectancy through socioeconomic factors .... 8 Literacy and socioeconomic factors ................................................................................... 8 Socioeconomic factors and life expectancy ..................................................................... 11 How are literacy, socioeconomic factors and life expectancy linked? ............................. 12 Exploring the link between literacy and life -

13B Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

13B bus time schedule & line map 13B Newham Grange - Hemlington View In Website Mode The 13B bus line Newham Grange - Hemlington has one route. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Hemlington: 6:47 AM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 13B bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 13B bus arriving. Direction: Hemlington 13B bus Time Schedule 66 stops Hemlington Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 6:47 AM Nightingale Drive, Newham Grange Hebburn Road, Stockton-On-Tees Tuesday 6:47 AM Humbledon Road, Newham Grange Wednesday 6:47 AM Humbledon Road, Stockton-On-Tees Thursday 6:47 AM The Vale, Newham Grange Friday 6:47 AM Darlington Lane, Stockton-On-Tees Saturday Not Operational Norwich Avenue, Elm Tree Clover Court, Stockton-On-Tees Felton Lane, Fairƒeld Darlington Back Lane, Stockton-On-Tees 13B bus Info Direction: Hemlington Fordwell Road, Fairƒeld Stops: 66 Trip Duration: 81 min Torwell Drive, Fairƒeld Line Summary: Nightingale Drive, Newham Grange, Rimswell Road, Stockton-On-Tees Humbledon Road, Newham Grange, The Vale, Newham Grange, Norwich Avenue, Elm Tree, Felton Rimswell Road South End, Fairƒeld Lane, Fairƒeld, Fordwell Road, Fairƒeld, Torwell Drive, Fairƒeld, Rimswell Road South End, Fairƒeld, The The Rimswell, Fairƒeld Rimswell, Fairƒeld, Bishopton Court, Fairƒeld, The Avenue, Fairƒeld, Castle Close, Elm Tree, Sixth Form Bishopton Court, Fairƒeld College, Newtown, Loweswater Crescent, St Mark's Close, Stockton-On-Tees Grangeƒeld, Spennithorne Road, Grangeƒeld, Ambulance -

DYING BEFORE OUR TIME? Achieving Longer and Healthier Lives in Middlesbrough

DYING BEFORE OUR TIME? ACHIEVING LONGER AND HEALTHIER LIVES IN MIDDLESbrougH Middlesbrough DPH Annual Report 2016/17 middlesbrough.gov.uk DYING BEFORE OUR TIME? ACHIEVING LONGER AND HEALTHIER LIVES IN MIDDLESbrougH Middlesbrough DPH Annual Report 2016/17 CONTENTS Foreword ............................................................................................................................. 04 Progress against 2015/16 recommendations ............................................................ 05 Chapter 1 ....................................................................................................................... 06 Overview of life expectancy and healthy life expectancy in Middlesbrough Chapter 2 Cancer ......................................................................................................... 18 Chapter 3 Circulatory diseases ................................................................................ 27 Chapter 4 Respiratory diseases ................................................................................ 33 Chapter 5 External causes ......................................................................................... 38 (accidents and injuries, suicide, alcohol and drugs misuse) Chapter 6 Infant mortality and child deaths ......................................................... 49 Chapter 7 Excess winter mortality ........................................................................... 52 Chapter 8 Recommendations .................................................................................. -

Brookfield-Woods-Brochure-Spread

tory OMES WELCOME TO YOUR BROOKFIELD WOODS SANCTUARY STORY HOMES IS RENOWNED FOR ITS HIGH SPECIFICATION, QUALITY HOMES Whether you’re looking for your first home, or you need more space for a growing family, you’ll be spoilt for choice at Brookfield Woods, where you’ll discover a fantastic selection of 3, 4 and 5-bedroomed properties. As well as offering an unrivalled choice of property location, house types and sizes, we always strive to go that extra mile, and that isn’t just when we build your new home; it starts from the very first design meeting. We mix property types and external finishes to create beautiful and unique street scenes. A Story Homes development looks as good now as it did when it was built, even if that was 20 years ago. We’ve won many awards along the way and we are proud that our buyers can boast that they live on award-winning developments. Our homes combine practical features with 21st century design incorporating fully fitted kitchens and contemporary bathrooms. Our kitchens are spacious, usually with a dining area, whilst bi-fold doors in most properties allow the living space to be continued with easy access to the garden, effectively extending the usable space for your family to enjoy. And remember we include many extras as standard in your new home too (see ‘The Finer Details’ page). A VIBRANT LOCATION MIDDLESBROUGH IS A LARGE TOWN SITUATED ON THE SOUTH BANK OF THE RIVER TEES, A STONE’S THROW FROM THE NORTH YORKSHIRE DALES. Brookfield Woods is located in Stainsby, a sought after area that is already home to our popular Kingsbrook Wood development and is ideally located for sights, amenities and transport links.