Korean American Youth by Autumn Koo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Korean Holy Martyrs

Korean Holy Martyrs SAINT OF THE DAY 20-09-2020 “Since we cannot find any means of changing the minds of Christians, it is imperative that they die in order to destroy the germ of their madness”. This was the edict of King Sunjo in 1802, which ratified the persecutions that had already been taking place since the end of the 18th century. Just then the first Korean Christian community was born in a unique way, on the initiative of lay people. Its history deserves at least a mention. In Korea some writings by Matteo Ricci and other missionaries who had evangelized China had been circulating for about two centuries . When Yi Byeok, eager to learn more about Christianity, heard that his friend Yi Seung- hun was leaving for a diplomatic mission, he advised him to be baptized in China and begged him to return with some books. His friend followed his advice. He returned with Christian books, crucifixes and a significant baptismal name: Peter. It was 1784. Soon the number of Christians increased, but the lack of clergy was a problem. The first priest arrived from China around 1795, after the bishop of Beijing had informed the embryonic Korean community of the need for apostolic succession in order to have legitimate pastors and be in communion with the Church. The faith of the Koreans survived the persecutions of 1801, during which the only priest was also killed, and was revived from 1837 on when the first bishop, Laurent Imbert, of the Society for Foreign Missions in Paris, arrived. Monsignor Imbert suffered martyrdom two years later, but soon other bishops and missionaries entered Korea thanks also to the work of young people like Andrew Kim Taegon, who became the first indigenous priest. -

St. Simon Berneux Catholic.Net

St. Simon Berneux Catholic.net The Korean Martyrs were the victims of religious persecution against Catholic Christians during the 19th century in Korea. At least 8,000 (as many as 10,000) adherents to the faith were killed during this period, 103 of whom were canonized en masse in May 1984. Paul Yun Ji-Chung and 123 companions were declared "Venerable" on February 7, 2014, and on August 16, 2014, they were beatified by Pope Francis during the Asian Youth Day in Gwanghwamun Plaza, Seoul, South Korea. There are further moves to beatify Catholics who were killed by communists for their faith in the 20th century during the Korean War. Background At the end of the 18th century Korea was a country ruled by the Joseon Dynasty. It was a society based on Confucianism with its hierarchical, class relationships. There was a small minority of privileged scholars and nobility while the majority were commoners paying taxes, providing labour and manning the military. Below them was the slave class. Even though it was scholars who first introduced the Gospel to Korea, it was the ordinary people who flocked to the new religion. The new believers called themselves "Chonju kyo udul" literally "friends of the teaching of God of Heaven". The term "friends" was the only term in the Confucian understanding of relationships which implied equality. History During the early 17th century, Christian literature written in Chinese was imported from China to Korea. On one of these occasions, around 1777, Christian literature obtained from Jesuits in China led educated Korean Christians to study. -

Mass Schedule ~

Church Address: 941 Lexington St., Santa Clara, CA 95050 Office Address: 725 Washington St., Santa Clara, CA 95050 Office: (408) 248-7786 ~ Fax: (408) 248-8150 E-mail: [email protected] Web-site: www.stclareparish.org Emergency: (408) 904-9187 September 17th, 2017 ~ 24th Sunday In Ordinary Time ~ Mass Schedule ~ WEEKDAYS - Rectory Chapel: Mon, Wed, Fri, & Sat 8:00 am ~ Tue & Thu 5:30 pm SATURDAY: Reconciliation 4:15-4:45 pm ~ Vigil Mass 5:00 pm SUNDAY: 7:45 am (English) ~ 9:00 am (English - Family) ~ 10:30 am (Portuguese) ~ 12:00 pm (Spanish) ~ 1:30 pm (Cantonese) ~ 3:00 pm (Mandarin) ~ 5:30 pm (English) Pastoral Staff: (408) 248-7786 Pastor’s Notes Pastor: Rev. Tadeusz Terembula, x104, Dear Parishioners, [email protected] Last Thursday we have celebrated the Feast of the Exaltation of Parochial Vicar: Rev. Prosper Molengi, the Holy Cross. We live in a world where debates among strangers x105, [email protected] can rage across an Internet blog. We recognize that everyone seems to Priest in Residence: Fr. Andrew Salapata have an opinion and we accept that everyone is entitled to that opinion. Office Manager: Joanna Ayllon, x106 We applaud a broad egalitarianism where anyone can follow their own Religious Education Coordinator and heart, create their own rules, establish their own religious laws, or choose Hispanic Ministry Coordinator: to not believe anything at all. Paty Rascon, x102 But is this really okay? Is this really God’s plan of salvation? The Facility Emergencies: Scripture prescribed for day was pretty clear. Perhaps it is imperative that Matt Dutra (408) 904-9181 we look again at “the essentials.” Saint Clare School: First, Almighty God created the world and everything in it. -

Andrew Kim Taegon

Andrew Kim Taegon This is a Korean name; the family name is Kim. of the Catholic Church, p.118, Richardson and Son, Lon- don, 1859 Saint Kim Taegon Andrea (Hangul: , Hanja: ) (1821–1846), generally referred to as Saint An- drew Kim Taegon in English, was the first Korean-born 2 Bibliography Catholic priest and is the patron saint of Korea. In the late 18th century, Roman Catholicism began to take root • “The Lives of the 103 Korean Martyr Saints (2): slowly in Korea[1] and was introduced by laypeople. In St. Kim Tae-gon Andrew,” Catholic Bishops’ Con- 1836 Korea saw its first consecrated missionaries (mem- ference of Korea Newsletter No. 27 (Summer 1999). bers of the Paris Foreign Missions Society) arrive,[2] only to find out that the people there were already practicing Catholicism. 3 External links Born of yangban, Kim’s parents were converts and his fa- ther was subsequently martyred for practising Christian- • Andrew Kim Taegon, Paul Chong Hasang and Com- ity, a prohibited activity in heavily Confucian Korea. Af- panions ter being baptized at age 15, Kim studied at a seminary • in the Portuguese colony of Macau. He also spent time in Saint Kim Dae Gon study at Lolomboy, Bocaue, Bulacan, Philippines, where a statue of him stands in a village. He was ordained a priest in Shanghai after nine years (1844) by the French bishop Jean-Joseph-Jean-Baptiste Ferréol. He then re- turned to Korea to preach and evangelize. During the Joseon Dynasty, Christianity was suppressed and many Christians were persecuted and executed. Catholics had to covertly practise their faith. -

Archbishop Smith: 감사합니다

Archbishop Smith: 감사합니다 감사합니다 That’s “thank you” in Korean. I’ve been saying that a lot these last number of days. That’s because it is the only thing I CAN say in the Korean language. Archbishop Richard W. Smith with Archbishop Hyginus Kim Hee-jong and Auxiliary Bishop Simon Ok Hyun-jjn. In point of fact, to say 감사합니다 is the reason I’ve travelled to Korea, from where I am writing this particular blog post. For over twenty years, the Archdiocese of Gwangju, in the southwestern part of the country, has been making priests available to care for the members of St. Jung Ha Sang Parish, the Korean Catholic community in Edmonton. For years the parish has been inviting me to visit this land, and finally I have been able to make the timing work, in coordination with Archbishop Kim Hee-jong, and his Auxiliary Bishop Ok Hyun-jjn. So, for this wonderful expression of solidarity and support towards our Korean parish and our local Church in general, I am here to bring the thanks of the clergy and lay faithful of the Archdiocese of Edmonton. Archbishop Smith with Archbishop John Hung Shan-chuan, S.V.D or Taiwan. My journey began with a two-day stopover in Taiwan to visit with a friend from university days of old. It was great to see him and to catch up on what has been happening in his life. It also afforded me the opportunity to pay a visit to the Archbishop of Taipei, Most Rev. John Hung Shan-Chuan, to learn about and see a bit of what is happening in that local Church, and also to thank him for the gift of one of his priests who served our Chinese parish of Mary Help of Christians for a few years. -

103 Korean Martyr Saints Testimoni Biografiedalmondo

Korean Martyr Saints - http://english.cbck.or.kr/Saints103 - http://www.cbck.or.kr/page/saint_kr_list.asp?p_code=K3400 * In consideration of the status, ecclesial role and family relationship, we selected 18 saints among 103 Martyr Saints, as follows: [List] <1>1 Andreas Kim Tae-gon, Priest (1821-1846) <2> Paulus Chong Ha-sang (1795-1839) <11> Lucia Pak Hui-sun (1801-1839)/ <25> Maria Pak Kun-a-gi (1786-1839)2 <30> Agnes Kim Hyo-ju (1816-1839)/ <44> Columba Kim Hyo-im (1814-1839)3 <31> Franciscus Choe Kyong-hwan (1805-1839) <32> Laurentius Imbert, Bishop (1797-1839) <33> Petrus Maubant, Priest (1803-1839) <35> Auguestinus Yu Chin-gil (1791-1839) <49> Caecilia Yu So-sa (1761-1839) <54> Elisabeth Chong Chong-hye (1797-1839) <72> Carolus Hyon Song-mun (1799-1846) <85> Ioannes B. Nam Chong-sam (1812-1866) <90> Antonius Daveluy (1818-1866) <93> Ioseph Chang Chu-gi (1802-1866) <94> Lucas Hwang Sok-tu (1811-1866) <103> Ioannes Yi Yun-il (1812-1867) 1 The number shown in front of the name of the saints is the serial number given to him or her among 103 Mar- tyr Saints. 2 The biography of these two saints is written in one. 3 The biography of these two saints is written in one. <1> Andreas Kim Tae-gon, Priest (1821-1846) 1) Family Background Kim Tae-gon Andrew was born on August 21st, 1821, in Solmae, Naepo, Chungchong Prov- ince. His great-grandfather, Kim Chin-hu Pius, was the son of a famous noble family in Sol- mae and once was an official of the regional government. -

Knightly News

KNIGHTLY NEWS JUNE 2017 ISSUE ST. STEPHEN COUNCIL 14084 From Our Worthy A Spectacular Opening Grand Knight Time for Preparing t’s hard to believe the fraternal year has gone by. When I Ithink of all of the things we accomplished and participated in, it is quite a lot. Every month our directors have been running multiple events that have added up to many hours of service, dollars raised, and entertaining social events. At our business meeting, I was proud to recognize some of our best supporting Knights who completed the Grand Knight’s Challenge this he Cross and the Light musical, Columbiettes and Squires were front-and- year. These are some of the Knights which premiered at St. Stephen center to helping The Cross and the Light that have supported a majority of last month, was more than be the spectacular event that it was. our programs. Faithful Knight just a grand show – it was an Parking support is one of the ways the pins were awarded to Brothers Topportunity to reach out and evangelize. It Knights have traditionally supported the Jerry Coffey, Bob Haley, Mark was a way to make a difference by opening efforts of our parish. And the musical was Lovejoy, Rich Sarnowski, Randy our new church to the community. It was no exception. Tim Donahue spearheaded Lee, and Bruce Czaja. It is not a way to unite parishioners in stewardship, the scheduling of a large number of parking too late to receive yours! If you which was evident by the over 300 volunteers who were instrumental in have completed 7 out of the 10 volunteers who came in droves to be part moving hundreds of automobiles in and out categories of Church, Community, of this opportunity. -

20150920.Pdf

Good Shepherd Parish 2021 Decherd Blvd Phone (931) 967-0961 Website: goodshepherdtn.com Decherd, TN 37324 [email protected] Emergency Contact Number—931-636-2742 Fr. Jean-Baptiste Kyabuta, Pastor Sat 5:00 pm Deacon Philip Johnson, DRE Sun 8:00 am St. Margaret Mary Caroline Woods, Dir. Admin. Services 10:30 am Patty Davidson, Religious Ed Coordinator/ 2:00 pm Spanish Mass Youth Minister Tue 9:00 am David Gallagher, Bookkeeper Wed 9:00 am Communion Service Karen Herget, Safe Environment Coordinator Thu 9:00 am Marie Habbick, Volunteer Secretary 7:00 pm Spanish Mass Fri 9:00 am Parish Council Finance Board Holy Day Masses at Good Shepherd Ron Fernandez Deacon Philip Johnson 10:00 am & 7:00 pm Anne-Marie Pender John Nauseef Subject to change. Please check Upcoming Events/Page 1 Mercy Hall Bob Knies Linda Holcomb Linda Holcomb Deacon Philip Johnson Bruce Rawson Sacraments Baptism: Please contact the Church Office to Caroline Woods determine how to begin the process of planning a John Casey Ex-Officio baptism. Marie Robey David Gallagher Burt Barrett First Communion: Please contact our DRE, Deacon Philip Johnson at the Church Office, for Diane Holcomb more information. Pam Wiedemer Mike Wiedemer Reconciliation: Confessions are heard at 4:00 p.m. RCIA on Saturday or by appointment. Bruce Rawson Please contact Angel Amador Deacon Philip Johnson Confirmation: Please contact our DRE, Deacon Philip Johnson, at the Church Office for more Patty Davidson 931-924-4511 information. RCIA: Rite of Christian Initiation of Adults: Contact: Deacon Philip Johnson (931) 924-4511. Good Shepherd Mission Statement Matrimony: Please contact the Parish Office at We, the members of Good Shepherd Parish, are joined least six months before the proposed date. -

St. Andrew Kim Taegon Catholic.Net

St. Andrew Kim Taegon Catholic.net Andrew Kim Tae-gon was born on 21 August 1821, in Chungchong Province, Korea. His parents, being converts to Catholicism, were subject to persecution, to avoid which they moved to Kyonggi Province. At 15 years old, Kim Tae-gon was chosen by a visiting priest to be a seminarian, and was sent with two other seminarians to Macao. He arrived in 1873 and began his studies with the missionaries of the Far Eastern Procure of the Parish Foreign Mission Society. In 1842 Kim Tae-gon left Macao as an interpreter for a French admiral aboard a warship. When the admiral returned to France, Kim Tae-gon tried to return to his homeland through the strictly guarded norther frontier, but he failed. He was ordained a deacon in China in 1844 and managed to return to Korea the next year, arriving in Seoul early in 1845. He then led the French missionaries by sea to Shanghai, where Bishop Ferreol ordained him the first Korean priest in the Church’s 60-year history in Korea. He returned to Korea with Bishop Ferreol, reaching Chungchong Province in October of the same year. In his home town and vicinity, he catechized the faithful, until Bishop Ferreol summoned him to Seoul. At the Bishop's command, he tried to introduce French missionaries from China into Korea, enlisting the aid of Chinese fishermen. For this, Father Kim Tae-gon was arrested and sent to the central prison in Seoul, where was charged as the ringleader of a heretical sect and traitor to his country. -

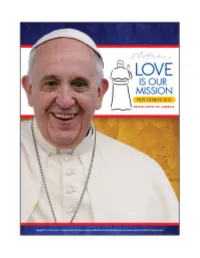

The Moving Pictures of Pope Francis in South Korea Remind Us, Once

20th Sunday (A) 17 th August 2014 the 18 th /19th c. in Korea was an era of outstanding witness ‘The blood of Martyrs is the seed of the Church ’ to Christ. It’s borne fruit in Korea today, such that the Is 56: I will bring foreigners to my holy mountain Ps 66: May … the ends of the earth revere Him Rom 11: Israel’s disobedience, and pagan obedience. Church there has grown by 70% in ten years: there are over Mt 15: 21–28: cure of Canaanite woman. 5m Catholics in that country, and almost 5000 priests! The moving pictures of Pope Francis in South Korea The Church has often said, since way back in the remind us, once again, of the global reach of the Catholic persecutions and martyrdoms in Rome under the Roman Church — the one true ‘world religion,’ reaching as it does Emperors, that “the blood of the martyrs is the seed of the to all the parts of the world. The Church in Korea is Church.” Far from discouraging conversion, the witness of relatively young: the first known baptized Catholic in that a life given for Christ is a great spur to know that faith is country was from the end of the 18 th c. And yet, in the meaningful, life-giving, important. Faith is more important course of the 19 th c., the Church there grew, but was than preserving one’s earthly life. “What does it profit a persecuted mercilessly by the state, on account of the fact man to keep his life, but lose his soul?” says Jesus. -

Knights of Columbus

JUN 17 E COVERS 5_12.qxp_Layout 1 5/12/17 2:42 PM Page 1 JUNE 2017 KNIGHTSOFCOLUMBUS COLUMBIA June Columbia 2017 ENG V1_Layout 1 5/12/17 12:48 PM Page 1 # in Overall Shopping Experience* ## in Overall Purchasing Experience* *Study: LIMRA CxP Customer Experience Find an agent at kofc.org Benchmarking Program, November 2016 or 1-800-345-5632 LIFE INSURANCE DISABILITY INSURANCE LONG-TERM CARE INSURANCE RETIREMENT ANNUITIES JUN 17 E 5_15 FINAL.qxp_Mar E 12 5/15/17 4:09 PM Page 1 KNIGHTSOFCOLUMBUS j u n e 2 0 1 7 ♦ V o l u m e 9 7 ♦ n u m b e r 6 COLUMBIA FEATURES 8 Calling for Peace in Egypt Pope Francis addresses persecuted Christians and gov- ernment leaders during his apostolic journey to Egypt. BY JOHN L. ALLEN JR. 14 Korea’s Martyred Mothers Seoul’s ‘Mothers’ Shrine’ celebrates the faith of women killed in one of Korea’s great persecutions. BY ALEX JENSEN 18 Generations of Brotherhood For many Knights, service to the Church and the Order is a family tradition uniting fathers, sons and grandsons. BY MATT HADRO 22 A ‘Miraculous Way’ for Student Moms North Carolina Knights support a unique residence for single mothers pursuing a college education. BY SUEANN HOWELL Jewels of office held by members of the Hassan family, which includes four generations of grand knights and district deputies, are pictured at the Hassan family home in Warrenton, Va. (see article on p. 8). DEPARTMENTS 36Building a better world Knights of Columbus News 13 Fathers for Good Our Order’s presence in Korea has Supreme Knight Meets With Our children need to learn that given the Knights an extraordinary Knights, Leaders in South Korea the wonders of the Catholic faith opportunity to serve the Church. -

Homily for September 20, 20171 the First Native Korean Priest, Andrew Kim Taegon Was the Son of Christian Converts

1 Homily for September 20, 20171 The first native Korean priest, Andrew Kim Taegon was the son of Christian converts. Following his baptism at the age of 15, Andrew traveled 2100 kilometres to the seminary in Macao, China. After six years, he managed to return to his country through Manchuria. That same year he crossed the Yellow Sea to Shanghai and was ordained a priest. Back home again, he was assigned to arrange for more missionaries to enter by a water route that would elude the border patrol. He was arrested, tortured, and finally beheaded at the Han River near Seoul, the capital at the age of 25. Andrew’s father Ignatius Kim, was martyred during the persecution of 1839, and was beatified in 1925. Paul Chong Hasang, a lay apostle and married man, also died in 1839 at age 45. Among the other martyrs in 1839 was Columba Kim, an unmarried woman of 26. She was put in prison, pierced with hot tools and seared with burning coals. She and her sister Agnes were disrobed and kept for two days in a cell with condemned criminals, but were not molested. After Columba complained about the indignity, no more women were subjected to it. The two were beheaded. Peter Ryou, a boy of 13, had his flesh so badly torn that he could pull off pieces and throw them at the judges. He was killed by strangulation. Protase Chong, a 41-year-old nobleman, apostatized under torture and was freed. Later he came back, confessed his faith and was tortured to death.