Streets Apart

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Men Who Buy Sex Who They Buy and What They Know

-RKQ -DFN -DPHV &KULV 5REHUW -RKQ 7DULT -RVHSK 7RP /HUR\ 3DXO +DUU\ 0DUN -RKQ 2OLYHU 6LPRQ 5RQ $OH[ 'DQLHO 5\DQ 0(1:+2%8<6(; :KRWKH\EX\DQGZKDWWKH\NQRZ 6SHQW5HSRUW&RYHUYLQGG Men who buy sex Who they buy and what they know A research study of 103 men who describe their use of trafficked and non-trafficked women in prostitution, and their awareness of coercion and violence. Melissa Farley, Julie Bindel and Jacqueline M. Golding December 2009 Eaves, London Prostitution Research & Education, San Francisco 2 CONTENTS 1. Acknowledgements 5 2. Introduction 6 3. Methodology 7 4. Results 8 Selected comments by London men who buy sex (Table 1) 8 4.1 Sample demographics 8 4.1i Age (Table 2) 8 4.1ii Ethnic identities 9 4.1iii Family income 9 4.1iv Family educational background 9 4.1v Religion 9 4.2 Number of sex partners and number of women used in prostitution 9 4.3 Age and circumstances when first bought sex 10 4.4 Locations where men purchased sex in London 10 Table 3 11 4.5 Buying sex during service in the Armed Forces 11 4.6 Buying sex outside the UK 11 Table 4 12 4.7 Rape and prostitution myth acceptance and hostile masculinity 13 4.8 The theory that prostitution is rape prevention 13 4.9 Awareness of age at entry into prostitution 14 4.10 Awareness of minors in strip clubs and massage parlours 14 4.11 Awareness of childhood abuse 14 4.12 Awareness of homelessness 14 4.13 Awareness of the psychological damage caused by prostitution 14 4.14 Awareness of pimping, trafficking and coercive control 15 4.15 The myth of mutuality in prostitution 17 Table 5 18 Table 6 19 4.16 Reasons men offer for buying sex 20 Table 7 20 4.17 Sexualisation and commodification of race/ethnicity 21 4.18 Frequency of pornography use 21 4.19 Deterrence 22 Table 8 22 4.20 Men’s ambivalence about prostitution 23 5. -

Wrong Kind of Victim? One Year On: an Analysis of UK Measures to Protect Trafficked Persons

Northern Ireland Supriya Begum, 45 South Asia trafficked for domestic servitude Scotland Abiamu Omotoso, 20 West Africa trafficked for sexual exploitation Aberdeen▪ Stirling▪ ▪ Glasgow Dumfries ▪Londonderry ▪ /Derry ▪ Belfast Leeds ▪ Blackpool ▪ Conwy ▪ Manchester Anglesey ▪ ▪Liverpool ▪ Sheffield London Wales Swansea Newport ▪ Cardiff Slough ▪▪ Bristol ▪ Mikelis Ðíçle, 38 Bridgend▪ ▪ ▪ Dover▪ Latvia ▪Portsmouth trafficked for Torquay forced labour ▪ England Tuan Minh Sangree,16 Vietnam trafficked for forced labour in cannabis farms Wrong kind of victim? One year on: an analysis of UK measures to protect trafficked persons. June 2010 Front Cover The cases on the cover refer to real cases of trafficked persons identified in the course of the research for this report. The names were changed and ages approximated to protect the identity of these individuals. The places indicated on the map are examples of some of the locations where cases of trafficking were identified in the course of the research for this report. This is by no means an exhaustive list. This report has been produced by the Anti-Trafficking Monitoring Group with Mike Dottridge Researcher: Lorena Arocha Coordinator: Rebecca Wallace Design and layout: Jakub Sobik ISBN: 978-0-900918-76-6 © Anti-Slavery International for the Anti-Trafficking Monitoring Group Acknowledgements This report has been made possible due to the information and advice provided by the Members of the Anti-Trafficking Monitoring Group and a variety of individuals, organisations and agencies across the UK and beyond who have shared their experience of working with trafficked persons. The Monitoring Group works closely with the Anti-Trafficking Legal Project (ATLeP). Contributions were received under the agreement that names of individuals and organisations would not be cited unless specifically requested. -

Railways: Thameslink Infrastructure Project

Railways: Thameslink infrastructure project Standard Note: SN1537 Last updated: 26 January 2012 Author: Louise Butcher Section Business and Transport This note describes the Thameslink infrastructure project, including information on how the scheme got off the ground, construction issues and the policy of successive government towards the project. It does not deal with the controversial Thameslink rolling project to purchase new trains to run on the route. This is covered in HC Library note SN3146. The re- let of the Thameslink passenger franchise is covered in SN1343, both available on the Railways topical page of the Parliament website. The Thameslink project involves electrification, signalling and new track works. This will increase capacity, reduce journey times and generally expand the current Thameslink route through central London and across the South East of England. On completion in 2018, up to 24 trains per hour will operate through central London, reducing the need for interchange onto London Underground services. The project dates back to the Conservative Government in the mid-1990s. It underwent a lengthy public inquiry process under the Labour Government and has been continued by the Coalition Government. However, the scheme will not be complete until 2018 – 14 years later than its supporters had hoped when the scheme was initially proposed. Contents 1 Where things stand: Thameslink in 2012 2 2 Scheme generation and development, 1995-2007 3 2.1 Transport and Works Act (TWA) Order application, 1997 5 2.2 Revised TWA Order application, 1999 6 2.3 Public Inquiry, 2000-2006 6 2.4 New Thameslink station at St Pancras 7 This information is provided to Members of Parliament in support of their parliamentary duties and is not intended to address the specific circumstances of any particular individual. -

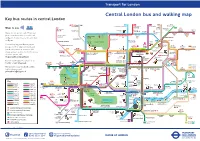

Central London Bus and Walking Map Key Bus Routes in Central London

General A3 Leaflet v2 23/07/2015 10:49 Page 1 Transport for London Central London bus and walking map Key bus routes in central London Stoke West 139 24 C2 390 43 Hampstead to Hampstead Heath to Parliament to Archway to Newington Ways to pay 23 Hill Fields Friern 73 Westbourne Barnet Newington Kentish Green Dalston Clapton Park Abbey Road Camden Lock Pond Market Town York Way Junction The Zoo Agar Grove Caledonian Buses do not accept cash. Please use Road Mildmay Hackney 38 Camden Park Central your contactless debit or credit card Ladbroke Grove ZSL Camden Town Road SainsburyÕs LordÕs Cricket London Ground Zoo Essex Road or Oyster. Contactless is the same fare Lisson Grove Albany Street for The Zoo Mornington 274 Islington Angel as Oyster. Ladbroke Grove Sherlock London Holmes RegentÕs Park Crescent Canal Museum Museum You can top up your Oyster pay as Westbourne Grove Madame St John KingÕs TussaudÕs Street Bethnal 8 to Bow you go credit or buy Travelcards and Euston Cross SadlerÕs Wells Old Street Church 205 Telecom Theatre Green bus & tram passes at around 4,000 Marylebone Tower 14 Charles Dickens Old Ford Paddington Museum shops across London. For the locations Great Warren Street 10 Barbican Shoreditch 453 74 Baker Street and and Euston Square St Pancras Portland International 59 Centre High Street of these, please visit Gloucester Place Street Edgware Road Moorgate 11 PollockÕs 188 TheobaldÕs 23 tfl.gov.uk/ticketstopfinder Toy Museum 159 Russell Road Marble Museum Goodge Street Square For live travel updates, follow us on Arch British -

Violence Against Women Uk

CEDAW Thematic Shadow Report on Violence Against Women in the UK VIOLENCE AGAINST WOMEN IN THE UK SHADOW THEMATIC REPORT For the COMMITTEE ON THE ELIMINATION OF ALL FORMS OF DISCRIMINATION AGAINST WOMEN DR PURNA SEN PROFESSOR LIZ KELLY LONDON SCHOOL OF ECONOMICS LONDON METROPOLITAN UNIVERSITY 2007 1 CEDAW Thematic Shadow Report on Violence Against Women in the UK THE AUTHORS Purna Sen, Development Studies Institute, London School of Economics Liz Kelly, Child and Woman Abuse Studies Unit, London Metropolitan University ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The authors would like to extend their appreciation to all those individuals and organisations involved in the consultation process and those who gave feedback and comments on the document. Thanks also to the Women’s National Commission for their support and facilitation of the consultation process. Particular thanks go to the Child and Woman Studies Unit, which has funded the writing of this report and its publication through a donation by the Roddick Foundation. DEDICATION This report is dedicated to the memory of Dame Anita Roddick, who passionately supported work against violence against women. Her legacy enabled this report to be produced. ORGANISATIONS THAT HAVE CONTRIBUTED TO OR ENDORSED THIS REPORT Amnesty UK Northern Ireland Women’s Aid Federation Domestic Violence Research Group, Poppy Project University of Bristol Rainbo Eaves Housing for Women Rape and Sexual Abuse Centre, Equality Now Merseyside End Violence Against Women Rape Crisis Scotland FORWARD Refugee Women’s Resource Project Greater -

Header 1, No Bigger Than 48 Point

STREET TALK: An evaluation of a counselling service for women involved in street based prostitution and victims of trafficking By Sarah Anderson, Esther Dickie and Caroline Parker November 2013 With thanks to Hannah Douglas and Turshia Park www.revolving-doors.org.uk Street Talk Evaluation Contents 1 Executive Summary 3 2 Background 16 3 Evaluation aims and methodology 17 3.1 Evaluation aims 17 3.2 Methodology 17 4 Literature review 20 5 Process evaluation: Results 26 5.1 Street Talk model 26 5.2 Client profiles 29 5.3 Client needs 30 5.3.1 Case file analysis 30 5.3.2 Stakeholder interviews 35 5.4 Interventions provided 41 5.4.1 Case file analysis 41 5.4.2 Stakeholder interviews 42 5.5 Effectiveness of service operation 49 5.5.1 Strengths 49 5.5.2 Model and implementation challenges 56 5.5.3 Areas for improvement 57 6 Outcome evaluation: Results 63 6.1 Primary outcomes 63 6.2 Secondary outcomes 68 7 Developing a Theory of Change 73 8 Conclusion and recommendations 74 9 Appendices 75 2 www.revolving-doors.org.uk Street Talk Evaluation 1 – Executive Summary Background Street Talk is a small charity providing psychological interventions (‘talking therapies’) alongside practical support, primarily to two groups of women: women who have been the victims of trafficking and those women involved in or exiting street based prostitution. Street Talk’s Mission Statement is: To provide professional and specialised mental health care of the highest quality to vulnerable women, including those in street based prostitution and those who have been the victims of trafficking. -

Sexed’ Regulation and the Disregarded Worker: an Overview of the Impact of Sexual Entertainment Policy on LapDancing Club Workers

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Lincoln Institutional Repository Social Policy and Society http://journals.cambridge.org/SPS Additional services for Social Policy and Society: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here Over ‘Sexed’ Regulation and the Disregarded Worker: An Overview of the Impact of Sexual Entertainment Policy on LapDancing Club Workers Rachela Colosi Social Policy and Society / FirstView Article / January 2006, pp 1 12 DOI: 10.1017/S1474746412000462, Published online: Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S1474746412000462 How to cite this article: Rachela Colosi Over ‘Sexed’ Regulation and the Disregarded Worker: An Overview of the Impact of Sexual Entertainment Policy on LapDancing Club Workers. Social Policy and Society, Available on CJO doi:10.1017/S1474746412000462 Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/SPS, IP address: 82.9.217.212 on 07 Oct 2012 Social Policy & Society: page 1 of 12 C Cambridge University Press 2012 doi:10.1017/S1474746412000462 Over ‘Sexed’ Regulation and the Disregarded Worker: An Overview of the Impact of Sexual Entertainment Policy on Lap-Dancing Club Workers Rachela Colosi School of Social Sciences, University of Lincoln E-mail: [email protected] In England and Wales, with the introduction of Section 27 of the Policing and Crime Act 2009, lap-dancing clubs can now be licensed as Sexual Entertainment Venues. This article considers such, offering a critique of Section 27, arguing that this legislation is not evidence-based, with lap-dancing policy, like other sex-work policies, often associated with crime, deviance and immorality. -

Technician North Carolina State University's Student Newspaper Since 1920 Volume LXLIL Number 8 Edward Robertson Makes a Telep

Technician North Carolina State University’s Student Newspaper Since 1920 Volume LXLIL Number 8 Friday, November 6. 181 Raleigh, North Carolina Phone 737-2411,-2412 UAB passes student fee increase by Gina Blackwaed “This increase is a result of infla» bills 53 percent and postage 38.5 per- “This fee increase would most likely Staff Writer tion. basically." Associate Dean of Stu- cent. keep us out of the red for the next four dent Affairs Henry Bowers said. “We years." Covington said. “This increase Union Activities Board members have been hit by it just like everybody However. according to Lee is projected to give us break-even voted Wednesday to raise student else. Careful consideration went into McDonald. there has been no increase balances. not a surplus of funds." fees 86 per semester and $2 per sum-. this decision (to ask for a fee in student activity fees for the UAB mer session. ' ‘ increasei." since 1978 when a 35 increase was The predicted increase will keep The increase must meet Provost enacted. services at their current level and will and Acting Chancellor Nash “The increase will benefit the not increase services due to the rising Winstead's approval before it is put operating budget of the Student At the Oct. 28 University Student costs of inflation. according to the into effect. It would raise the present Center. not the UAB itself." Cov- Center board ol directors meeting. minutes from the last UAB board of N.C. resident's tuition and fees to ing'ton said. “It will be used to pay McDonald presented two alternatives directors meeting. -

P&C Music Record Store Day 2017 – Remaining Stock

P&C MUSIC RECORD STORE DAY 2017 – REMAINING STOCK This list is dated 16 June 2017 ARTIST / TITLE PRODUCT INFO £ 1. 12 STONE TODDLER: Does it scare you? / Scheming 2 picture disc LPs in back-to-back packaging, first time on vinyl. 31.99 2. 999: Live and loud LP, yellow vinyl, 1000 hand-numbered copies with insert. 999 kicked off in 1977 with I’m Alive and 21.99 Nasty, Nasty, two riotous singles that established them alongside the Pistols, Clash and The Damned. This release reproduces the original background liners and includes rare archival photos. 3. AIR: Le soleil 12” single, splattered vinyl. Includes Le soleil est près de moi, J'ai dormi sous l'eau, Le soleil est 23.99 près de moi (Automator remix) and J'ai dormi sous l'eau (Chateau Flight Remix). 4. AIRBOURNE: It’s all for rock and roll / It’s never too 12” single on 180g opaque bronze vinyl. A side was written as a tribute to Lemmy from 16.49 loud for me Motorhead! BACK IN STOCK! 5. ALICE IN CHAINS: What the hell have I + 3 more Double gatefold containing 2 x 7” singles, containing four tracks. 500 copies for UK. 15.99 BACK IN STOCK! 6. ALTERED IMAGES: Happy birthday 2LP on 180g vinyl, re-mastered ltd edn. Contains a bonus disc of seven extra tracks. 31.99 7. ANDERSON, Brett: Live at Koko, 2011 LP, dark green vinyl. The inner sleeve features previously unpublished photos from the rehearsal 27.99 sessions. 8. ANIMALS, THE: Five animals don’t stop no show LP. -

158-160 Pentonville Rd Committe Report

Development Management Service PLANNING COMMITTEE REPORT Planning and Development Division Environment and Regeneration Department Town Hall Upper Street LONDON N1 2UD PLANNING COMMITTEE AGENDA ITEM NO:1 Date: 23 April 2020 Application number P2019/2290/FUL Application type Full Planning Application Ward Barnsbury Listed building n/a Conservation area n/a Strategic Central Activities Zone Kings Cross & Pentonville Road Key Area Employment Growth Area Article 4 Direction – A1 (Retail) to A2 (Professional and Financial Services) Article 4 Direction – B1c (Light Industrial) to C3 (Residential) CrossRail 2 Safeguarding Zone London Underground Zone of Interest (Tunnels) Licensing Implications n/a Site Address 158-160 Pentonville Road, London, N1 9JL Proposal Demolition of existing single storey building and erection of part one, part 4 storey plus basement office (Use Class B1(a)) with associated works (Departure from Development Plan)) Case Officer Simon Roberts Applicant Korbe Ltd Agent GML Architects Ltd 1. RECOMMENDATION 1.1. The Committee is asked to resolve to GRANT planning permission: subject to the conditions set out in Appendix 1; and conditional upon the prior completion of a Deed of Planning Obligation made under section 106 of the Town and Country Planning Act 1990 securing the heads of terms as set out in Appendix 1. 2. SITE LOCATION AND PHOTOS Figure 1: Site Plan (outlined in red) Figure 2: Aerial view from the south Figure 3: Aerial view from the north Figure 4: Photograph of the front elevation of the building from Pentonville Road Figure 5: Photograph showing the access from Cumming Street Figure 6: Photograph of the rear of the site 3. -

11/3/2019 Hawkwind on Television and Film File:///C:/Users/Stephen

11/3/2019 Hawkwind on television and film Do Not Panic - Film & Television List - DVD Trading ------ Galleries: Albums - Tickets - Programmes - DVD Artwork THE HAWKWIND ALBUMS There is no shortage of Hawkwind material on CD - official, semi-official & bootlegs of studio and live sessions. Not to mention countless compilations and repackaged discs which look exciting but turn out to be Wembley 1973 again. Here is my take on the major 'Official' releases followed by a collection of live CDs. You can pretty much ignore the rest - I don't know who advised Hawkwind that such wide-scale licensing was a good idea but it has devalued the core catalogue and made it difficult for new fans to know where to start. some of it is so dire it has probably deterred many who would otherwise have got into the quality we all know is there. 14 August 1970 - Hawkwind - 1st album released Hurry On Sundown / The Reason Is? / Be Yourself / Paranoia (part 1) / Paranoia (part 2) / Seeing It As You Really Are / Mirror Of Illusion Dave Brock - John Harrison - Nik Turner - Terry Ollis - Dik Mik - Huw Lloyd Langton - Mick Slattery 8 October 1971- In Search of Space - 2nd album released You Shouldn't Do That / You Know You're Only Dreaming / Master Of The Universe / We Took the Wrong Step Years Ago / Adjust Me / Children Of The Sun Nik Turner - Dave Brock - Dave Anderson - Del Dettmar - Terry Ollis - Dik Mik 24 November 1972 - Doremi Fasol Latido - 3rd album released Brainstorm / Space Is Deep / One Change / Lord Of Light / Down Through The Night / Time We Left This World Today / The Watcher Dave Brock - Nik Turner - Lemmy - Dik Mik - Del Dettmar - Simon King 11 May 1973 - Space Ritual Alive - 4th album released Earth Calling / Born To Go / Down Through The Night / The Awakening / Lord Of Light / The Black Corridor / Space Is Deep / Electronic No. -

Refugee Council the Vulnerable Women's Project

Refugee Council The Vulnerable Women’s Project Refugee and Asylum Seeking Women Affected by Rape or Sexual Violence Literature Review February 2009 Refugee Council The Vulnerable Women’s Project Refugee and Asylum Seeking Women Affected by Rape or Sexual Violence Literature Review February 2009 Acknowledgements Thanks go to Sarah Cutler, Gemma Juma, Nancy Kelley and Richard Williams (consultant), as well as Elena Hage and Andy Keefe from the Vulnerable Women’s Project, for their contributions to this report. We are grateful to Comic Relief for funding the Vulnerable Women’s Project and the publication of this literature review. 2 Refugee Council report 2009 Contents Executive Summary 4 Chapter One – Introduction 8 Chapter Two – The Refugee Council’s vulnerable women’s project 9 Chapter Three – Definitions 11 Chapter Four – How many refugee women are affected by rape, sexual assault or sexual exploitation? 13 Chapter Five – Sexual violence and exploitation in the UK 26 Chapter Six – Access to Justice 34 Chapter Seven – Access to health care 52 Chapter Eight – Conclusion 54 Bibliography 55 Appendix 1 62 The Vulnerable Women’s Project 3 Executive Summary Refugee women are more affected by violence form of violence in their lifetime – sexual assault, against women than any other women’s population stalking, or domestic violence. Although in most in the world and all refugee women are at risk of cases the perpetrator is an intimate partner, 20% – rape or other forms of sexual violence. Sexual 40% of women have experienced sexual assault by violence is regarded the UN as one of the worst men other than partners in their adult lifetime.