Local Government Auditor's Report – 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LISBURN & CASTLEREAGH CITY COUNCIL Island Civic Centre The

LISBURN & CASTLEREAGH CITY COUNCIL Island Civic Centre The Island Lisburn BT27 4RL 26 May, 2016 TO: The Right Worshipful the Mayor, Aldermen & Councillors of Lisburn & Castlereagh City Council The monthly meeting of Lisburn & Castlereagh City Council will be held in the Council Chamber, Island Civic Centre, The Island, Lisburn, BT27 4RL, on Tuesday, 31 May 2016 at 7.00 pm for the transaction of the business on the undernoted Agenda. You are requested to attend. Food will be available in Lighters Restaurant from 5.30 pm. DR THERESA DONALDSON Chief Executive Lisburn & Castlereagh City Council AGENDA 1 BUSINESS OF THE RIGHT WORSHIPFUL THE MAYOR 2 APOLOGIES 3 DECLARATION OF MEMBERS’ INTERESTS; (i) Conflict of interest on any matter before the meeting (Members to confirm the specific item) (ii) Pecuniary and non-pecuniary interest (Member to complete the Disclosure of Interest form) 4 COUNCIL MINUTES - Meeting of Council held on 26 April, 2016 5 MATTERS ARISING 6 DEPUTATIONS (None) 7 BUSINESS REQUIRED BY STATUTE (i) Signing of Legal Documents Northern Ireland Housing Executive of 2 Adelaide Street, Belfast to Lisburn and Castlereagh City Council – Memorandum of Sale in respect of purchase of land at Rushmore Avenue/Drive, Lisburn Lisburn and Castlereagh City Council and Mullinsallagh Limited of 28 Townhill Road, Portglenone, Ballymena, County Antrim, BT44 8AD – Contract – West Lisburn Youth Resource Centre and Laganview Enterprise Centre SIF Projects Education Authority of Forestview, Purdy’s Lane, Belfast, BT8 7AR and Lisburn and Castlereagh -

The Belfast Gazette, July 4, 1930. 837

THE BELFAST GAZETTE, JULY 4, 1930. 837 STATUTORY NOTICE BY THE MINISTRY i i No. Memorialist Amount Lands to be . Barony County. OP FINANCE, NORTHERN IRELAND. Charged. 84 William £120 Canow- 1 Upper Armagh Application has been made by the under- King mannon I Oiior mentioned for a loan under the Landed Dissents or objections, with reasons therefor, Property Improvement (Ireland) Acts (10 & 11 must be transmitted to the Ministry of Finance, Vic., Chap. 32, etc.), as made applicable to on or before the 26th July, 1930. Northern Ireland by virtue of the Government G. C. DUGGAN, of Ireland Act, 1920, and the Statutory Assistant Secretary. Orders made thereunder: — Ministry of Finance, Belfast, 26th June, 1930. PROVISIONAL LIST No. 1731. LAND PURCHASE COMMISSION, NORTHERN IRELAND. NORTHERN IRELAND LAND ACT, 1925. ESTATE OF SOLOMON HENRY DARCUS. County of Antrim. Record No. N.I. 1515. WHEREAS the above-mentioned Solomon Henry Darcus claims to be the Owner of land in the Townland of B rowndod, Barony of Lower Belfast, and of land in the Townland of Ballymena, Barony of Lower Antrim, both in the County of Antrim: Now in pursuance of the provisions of Section 17, Sub-section 2, of the above Act the Land Purchase Commission, Northern Ireland, hereby publish the following Provisional List of all land in the said Townlands of which the said Solomon Henry Darcus claims to be the Owner, which will become vested in the said Commission by virtue of Part II of the Northern Ireland Land Act, 1925, on the Appointed Day to be hereafter fixed. -

254 the Belfast Gazette, 31St July, 1964 Inland Revenue

254 THE BELFAST GAZETTE, 31ST JULY, 1964 townlands of Castlereagh and Lisnabreeny in the Armagh County Council, 1, Charlemont Place, County of Down (hereinafter referred to as "the Armagh. Castlereagh substation"). Down County Council, Courthouse, Downpatrick. 2. A double circuit 275 kV tower line from the Co. Down. 275/110 kV transforming substation to be estab- Belfast County Borough Council, City Hall, Bel- lished at Tandragee under the No. 11 Scheme, fast, 1. 1962, to the Castlereagh substation via the north Antrim Rural District Council, The Steeple, side of Banbridge, the south east side of Dromore Antrim. and the west side of Carryduff. Banbridge Rural District Council, Linenhall Street, 3. A double circuit 275 kV tower line from the Banbridge, Co. Down. 275/110 kV transforming substation within the Castlereagh Rural District Council, 368 Cregagh boundaries of the power station to be established Road, Belfast, 6. at Ballylumford, Co. Antrim, under the No. 12 Hillsborough Rural District Council, Hillsborough, Scheme, 1963, to the Castlereagh substation via Co. Down. the west side of Islandmagee, the north side of Larne Rural District Council, Prince's Gardens, Ballycarry, the south east side of S'traid, the east Larne, Co. Antrim. side of Hyde Park, the east and south east sides Lisburn Rural District Council, Harmony Hill, of Divis Mountain, the west side of Milltown and Lisburn, Co. Antrim. the south side of Ballyaghlis. Tandragee Rural District Council, Linenhall 4. Two double circuit 110 kV lines from the Castle- Street, Banbridge, Co. Down. reagh substation to connect with points on the existing double circuit 110 kV line between the Electricity Board for Northern Ireland, Danes- Finaghy and Rosebank 110/33 kV transforming fort, 120 Malone Road, Belfast, 9. -

Heart of the Glens Landscape Partnership Industrial Heritage Audit

Heart of the Glens Landscape Partnership Industrial Heritage Audit March 2013 Contents 1. Background to the report 3 2. Methodology for the research 5 3. What is the Industrial Heritage of the Antrim Coast and Glens? 9 4. Why is it important? 11 5. How is it managed and conserved today? 13 6. How do people get involved and learn about the heritage now? 15 7. What opportunities are there to improve conservation, learning and participation? 21 8. Project Proposals 8.1 Antrim Coast Road driving route mobile app 30 8.2 Ore Mining in the Glens walking trail mobile app 35 8.3 Murlough Bay to Ballycastle Bay walking trail mobile app 41 8.4 MacDonnell Trail 45 8.5 Community Archaeology 49 8.6 Learning Resources for Schools 56 8.7 Supporting Community Initiatives 59 Appendices A References 67 B Gazetteer of industrial sites related to the project proposals 69 C Causeway Coast and Glens mobile app 92 D ‘History Space’ by Big Motive 95 E Glenarm Regeneration Plans 96 F Ecosal Atlantis Project 100 2 1. Background to the report This Industrial Heritage Audit has been commissioned by the Causeway Coast and Glens Heritage Trust (CCGHT) as part of the development phase of the Heart of the Glens Landscape Partnership Scheme. The Causeway Coast and Glens Heritage Trust is grateful for funding support by the Heritage Lottery Fund for Northern Ireland and the NGO Challenge Fund to deliver this project. CCGHT is a partnership organisation involving public, private and voluntary sector representatives from six local authorities, the community sector, and the environment sector together with representatives from the farming and tourism industries. -

Northern Ireland

Status: This is the original version (as it was originally made). This item of legislation is currently only available in its original format. STATUTORY RULES OF NORTHERN IRELAND 1996 No. 474 ROAD TRAFFIC AND VEHICLES Roads (Speed Limit) (No. 7) Order (Northern Ireland) 1996 Made - - - - 7th October 1996 Coming into operation 18th November 1996 The Department of the Environment, in exercise of the powers conferred on it by Article 50(4)(c) of the Road Traffic (Northern Ireland) Order 1981(1) and of every other power enabling it in that behalf, hereby makes the following Order: Citation and commencement 1. This Order may be cited as the Roads (Speed Limit) (No. 7) Order (Northern Ireland) 1996 and shall come into operation on 18th November 1996. Speed restrictions on certain roads 2. The Department hereby directs that each of the roads and lengths of road specified in Schedule 1 shall be a restricted road for the purposes of Article 50 of the Road Traffic (Northern Ireland) Order 1981. Revocations 3. The provisions described in Schedule 2 are hereby revoked. Sealed with the Official Seal of the Department of the Environment on 7th October 1996. L.S. J. Carlisle Assistant Secretary (1) S.I.1981/154 (N.I. 1); see Article 2(2) for the definition of “Department” Document Generated: 2019-11-19 Status: This is the original version (as it was originally made). This item of legislation is currently only available in its original format. SCHEDULE 1 Article 2 Restricted Roads 1. Ballynafie Road, Route A42, Ahoghill, from its junction with Glebe Road, Route B93, to a point approximately 510 metres south-west of that junction. -

The Code of Practice for Film Production in Northern Ireland

THE CODE OF PRACTICE FOR FILM PRODUCTION IN NORTHERN IRELAND Northern Ireland Screen promotes Northern Ireland nationally and internationally as an important location for the production of films for cinema and television. Northern Ireland Screen provides a fully comprehensive information service, free of charge, to film and television producers from all over the world. WHY A CODE OF PRACTICE? Northern Ireland Screen is here to help complete projects safely and efficiently. We bring together all bodies affected by film-making and work with them and the general public to ensure a more film friendly environment. The creation of a code of practice for production companies to follow when filming on location in Northern Ireland will ensure closer co-operation with the public and better management on the ground. The object of this code of practice is to maximise Northern Ireland’s potential as a location while safe guarding the rights of its residents. Northern Ireland Screen encourages all feature film producers to agree to abide by this code of practice. NB: This Code of Practice is not intended for news and documentary crews of five persons or less. Whenever this document refers to film and film production, the term includes all other visual media such as television, commercials, corporate and music videos, cable, satellite etc. This document contains a declaration that all producers are requested to sign. NORTHERN IRELAND SCREEN 3rd Floor, Alfred House, 21 Alfred Street, Belfast BT2 8ED T: +44 28 9023 2444 F: +44 28 9023 9918 E: [email protected] -

Action Points from NILGA OB Meeting 2Nd March 2021

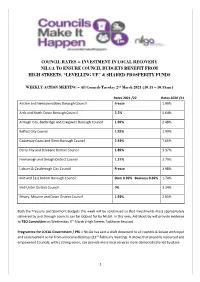

COUNCIL RATES = INVESTMENT IN LOCAL RECOVERY NILGA TO ENSURE COUNCIL BUDGETS BENEFIT FROM HIGH STREETS, “LEVELLING UP” & SHARED PROSPERITY FUNDS WEEKLY ACTION MEETING – All Councils Tuesday 2nd March 2021 (10.15 – 10.55am) Rates 2021 /22 Rates 2020 /21 Antrim and Newtownabbey Borough Council Freeze 1.99% Ards and North Down Borough Council 2.2% 5.64% Armagh City, Banbridge and Craigavon Borough Council 1.99% 2.48% Belfast City Council 1.92% 1.99% Causeway Coast and Glens Borough Council 2.49% 7.65% Derry City and Strabane District Council 1.89% 3.37% Fermanagh and Omagh District Council 1.37% 2.79% Lisburn & Castlereagh City Council Freeze 3.98% Mid and East Antrim Borough Council Dom 0.99% Business 0.69% 1.74% Mid Ulster District Council 0% 3.24% Newry, Mourne and Down District Council 1.59% 2.85% Both the Treasury and Stormont Budgets this week will be scrutinised so that investments most appropriately delivered by and through councils can be lobbied for by NILGA. In this vein, Ald Moutray will provide evidence to TEO Committee on Wednesday 3rd March (High Streets Taskforce Session). Programme for LOCAL Government / PfG – NILGA has sent a draft document to all councils & Solace with input and endorsement so far from all local authorities (22nd February meeting). It shows that properly resourced and empowered Councils, with a strong vision, can provide more local services more democratically led by place. 1 Economy - In May 2021, NILGA Full Members will be invited to an event to look at the new economic environment and councils’ roles in driving enterprise locally. -

Development Brief Introduction

DEVELOPMENT OPPORTUNITY AT THE ATLANTIC LINK ENTERPRISE CAMPUS PORTSTEWART ROAD, COLERAINE, CO. DERRY~LONDONDERRY, NORTHERN IRELAND. DEVELOPMENT BRIEF INTRODUCTION Causeway Coast and Glens Borough and sustainable economic use, Council is releasing 12 acres of land at with appropriate digital and creative the Atlantic Link Enterprise Campus, development schemes that are in Portstewart Road, Coleraine for accordance with Council’s vision development. and the Area Plan; thus supporting prosperity, economic development Interested parties are invited to and job creation within a satisfactory submit their proposals for the site timeframe. in accordance with the information presented in this document. In addition, Causeway Coast and Glens Borough Council is required to ensure Bid proposals in respect of this that it secures a sound financial return development opportunity are to be in any asset release. submitted on the basis of up to a 124 year leasehold. Interested parties are requested to read the submission requirements The prime objective in providing this and bid evaluation criteria which are opportunity is for Council to secure presented after the site information quality development that brings this overleaf. vacant opportunity site into viable 2 3 LOCATION CAMPUS The 12 acre site occupies a highly prominent position fronting Portstewart Road on the main road from Coleraine to Portstewart. The site is within the Planning Development Limit and benefits from close proximity to the amenities of Coleraine Town. Development on the site began in 2017 with anchor tenant 5NINES opening their first carrier neutral data centre in Northern Ireland. Londonderry Coleraine Ballymena Antrim 2 Omagh Belfast Lisburn Dungannon Armagh Newry 4 5 TITLE RATES The 20 acre site is held by way of a 125 No rates will be payable prior to completion of each year Leasehold from Ulster University. -

Councillor B Hanve

Lisburn and Castlereagh City Council Dr. Theresa Donaldson Chief Executive Island Civic Centre, The Island, Lisburn, BT27 4RL Tel: 028 9250 9451 Email: [email protected] www.lisburncity.gov.uk www.castlereagh.gov.uk Island Civic Centre The Island LISBURN BT27 4RL 26 March 2015 Chairman: Councillor B Hanvey Vice-Chairman: Councillor T Mitchell Councillors: Councillor N Anderson, Councillor J Baird, Councillor B Bloomfield, Councillor P Catney, A Givan, Councillor J Gray, Alderman T Jeffers, Councillor A McIntyre, Councillor T Morrow, Councillor J Palmer, Councillor L Poots, Alderman S Porter, Councillor R Walker Ex Officio Presiding Member, Councillor T Beckett Deputy Presiding Member, Councillor A Redpath The monthly meeting of the Environmental Services Committee will be held in the Chestnut Room, Island Civic Centre, The Island, Lisburn, on Wednesday, 1 April 2015, at 5.30 pm, for the transaction of business on the undernoted agenda. Please note that hot food will be available prior to the meeting from 5.00 pm. You are requested to attend. DR THERESA DONALDSON Chief Executive Lisburn and Castlereagh City Council Agenda 1. Apologies 2. Declarations of Interest 3. Minutes of the Environmental Services Committee meeting held on 11 March 2015 4. Report from Director of Environmental Services 1. Sub-Regional Animal Welfare Arrangements 2. Rivers Agency – Presentation on Flood Maps on Northern Ireland 3. Bee Safe 4. Dog Fouling Blitz 5. Service Delivery for the Environmental Health Service 6. Relocation of the Garage from Prince Regent Road 7. Adoption of Streets under the Private Streets (NI) Order 1980 as amended by the Private Streets (Amendment) (NI) Order 1992 8. -

Antrim, Ballymena & Moyle Area Plan 2016/2017

Education Authority Youth Service Local Assessment of Need 2018/2020 Causeway Coast and Glens Division 1 Causeway Coast and Glens Council 2018 Contents 1. Introduction .............................................................................................. 1 2. Policy Context ........................................................................................... 3 Introduction ........................................................................................................................................ 3 Draft Programme for Government 2016-2021 ................................................................................... 3 Department of Education ................................................................................................................... 4 Department of Education Business Plan ............................................................................................. 4 Priorities for Youth .............................................................................................................................. 5 Community Relations, Equality and Diversity (CRED) and CRED Addendum ..................................... 6 Shared Education ................................................................................................................................ 7 Rural Needs Act Northern Ireland 2016.............................................................................................. 8 3. Current Delivery ........................................................................................ -

Belfast MIPIM 2020 Delegation Programme

Delegation Programme Tuesday 10th March 09:00 Belfast Stand 10:00 - 10:45 Belfast Stand 11:00 – 11:45 Belfast Stand 12:00 - 14:00 Belfast Stand Opens Belfast Potential: Perfectly Positioned Belfast: City of Innovation - Investor Lunch Where Ideas Become Reality Tea, Coffee & Pastries Suzanne Wylie, Chief Executive, Belfast City Council By Invitation Only Speakers Scott Rutherford, Director of Research and Enterprise, Queen’s University Belfast Thomas Osha, Senior Vice President, Innovation & Economic Development, Wexford Science & Technology Petr Suska, Chief Economist and Head of Urban Economy Innovation, Fraunhofer Innovation Network Chair Suzanne Wylie, Chief Executive, Belfast City Council 14:15 – 14:55 Belfast Stand 15:00 – 15:45 Belfast Stand 16:00 Belfast Stand 18:00 Belfast Stand Sectoral focus on film and Our Waterfront Future: Keynote with Belfast Stand Closes Belfast Stand Reopens creative industries in Belfast Wayne Hemingway & Panel Discussion On-stand Networking Speakers Speakers James Eyre, Commercial Director, Titanic Quarter Wayne Hemingway, Founder, HemingwayDesign Joe O’Neill, Chief Executive, Belfast Harbour Scott Wilson, Development Director, Belfast Harbour Nick Smith, Consultant, Belfast Harbour Film Studios James Eyre, Commercial Director, Titanic Quarter Tony Wood, Chief Executive, Buccaneer Media Cathy Reynolds, Director of City Development and Regeneration, Belfast City Council Chair Stephen Reid, Chief Executive, Ards and North Down Borough Nicola Lyons, Production Manager, Northern Ireland Screen Council Chair -

Home Delivery of Groceries Ballymoney Area Spar Supermarket

Home Delivery of Groceries Ballymoney Area Spar Supermarket - Ballymoney 22 John Street, Ballymoney, BT53 6DS 028 2766 3150 . £20 and over around Ballymoney £3.50 charge if less than £20 order phone through order and pay cash. Ballymoney Town only at present. Brooklands Today’s Local - Ballymoney 1 Balnamore Road, Ballymoney, County Antrim, BT53 7PJ 02827662109 . 2mile radius Ballymoney and Balnamore minimum spends £20 Spar - Stranocum 2, Main Street, Stranocum, Ballymoney, BT53 8PE 028 2074 1245, Fax - 01303 261400 www.spar.co.uk [email protected] . Deliveries within a 3mile radius £20 minimum Spend Mace Dunloy 26 Main St, Dunloy, Ballymena, BT44 9AA 028 2765 7269 . Free delivery within a 4mile radius around Dunloy. Gas and coal delivery. Deliveries a few times a week. Will assess minimum spend case by case. Brollys Butchers Cloughmills 3 Main Street, Cloughmills 028 2763 8660 . Deliveries of meat/fresh produce to you to Older, Vulnerable and Isolating households. Fullan’s Spar - Rasharkin 27 - 33 Main Street, Rasharkin, BT44 8PU 028 2957 1211 . Home delivery in the local area around 1 mile radius. Free delivery for reasonable orders, will assess case by case. Order to be placed over the phone and cash paid on delivery. Costcutter - Kilrea Maghera Street, Kilrea 028 2954 0437 . Free delivery in a 3 mile radius. McAtamneys Butchers Home Delivery Ballymoney 028 276 68848 Meat products and ready made fresh meals . Call your local store to arrange delivery or collection, minimum spend £20 Sydney B Scott Delivery of Fruit Veg. And Essentials Essentials of fruit, veg, milk, butter and bread in readymade boxes.