To Act Or Not to Act Tiina Kikerpuu

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Dark Unknown History

Ds 2014:8 The Dark Unknown History White Paper on Abuses and Rights Violations Against Roma in the 20th Century Ds 2014:8 The Dark Unknown History White Paper on Abuses and Rights Violations Against Roma in the 20th Century 2 Swedish Government Official Reports (SOU) and Ministry Publications Series (Ds) can be purchased from Fritzes' customer service. Fritzes Offentliga Publikationer are responsible for distributing copies of Swedish Government Official Reports (SOU) and Ministry publications series (Ds) for referral purposes when commissioned to do so by the Government Offices' Office for Administrative Affairs. Address for orders: Fritzes customer service 106 47 Stockholm Fax orders to: +46 (0)8-598 191 91 Order by phone: +46 (0)8-598 191 90 Email: [email protected] Internet: www.fritzes.se Svara på remiss – hur och varför. [Respond to a proposal referred for consideration – how and why.] Prime Minister's Office (SB PM 2003:2, revised 02/05/2009) – A small booklet that makes it easier for those who have to respond to a proposal referred for consideration. The booklet is free and can be downloaded or ordered from http://www.regeringen.se/ (only available in Swedish) Cover: Blomquist Annonsbyrå AB. Printed by Elanders Sverige AB Stockholm 2015 ISBN 978-91-38-24266-7 ISSN 0284-6012 3 Preface In March 2014, the then Minister for Integration Erik Ullenhag presented a White Paper entitled ‘The Dark Unknown History’. It describes an important part of Swedish history that had previously been little known. The White Paper has been very well received. Both Roma people and the majority population have shown great interest in it, as have public bodies, central government agencies and local authorities. -

Coordination in Networks for Improved Mental Health Service

International Journal of Integrated Care – ISSN 1568-4156 Volume 10, 25 August 2010 URL:http://www.ijic.org URN:NBN:NL:UI:10-1-100957 Publisher: Igitur, Utrecht Publishing & Archiving Services Copyright: Research and Theory Coordination in networks for improved mental health service Johan Hansson, PhD, Senior Researcher, Medical Management Centre (MMC), Karolinska Institute, SE-171 77 Stockholm, Sweden John Øvretveit, PhD, Professor of Health Innovation Implementation and Evaluation, Director of Research, Medical Management Centre (MMC), Karolinska Institute, SE-171 77 Stockholm, Sweden Marie Askerstam, MSc, Head of Section, Psychiatric Centre Södertälje, Healthcare Provision, Stockholm County (SLSO), SE- 152 40 Södertälje, Sweden Christina Gustafsson, Head of Social Psychiatric Service in Södertälje Municipality, SE-151 89 Södertälje, Sweden Mats Brommels, MD, PhD, Professor in Healthcare Administration, Director of Medical Management Centre (MMC), Karolinska Institute, SE-171 77 Stockholm, Sweden Corresponding author: Johan Hansson, PhD, Senior Researcher, Medical Management Centre (MMC), Karolinska Institute, SE-171 77 Stockholm, Sweden, Phone: +46 8 524 823 83, Fax: +46 8 524 836 00, E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Introduction: Well-organised clinical cooperation between health and social services has been difficult to achieve in Sweden as in other countries. This paper presents an empirical study of a mental health coordination network in one area in Stockholm. The aim was to describe the development and nature of coordination within a mental health and social care consortium and to assess the impact on care processes and client outcomes. Method: Data was gathered through interviews with ‘joint coordinators’ (n=6) from three rehabilitation units. The interviews focused on coordination activities aimed at supporting the clients’ needs and investigated how the joint coordinators acted according to the consor- tium’s holistic approach. -

Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences Department of Forest Products, Uppsala Sustainable Urban Development Through Increas

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Epsilon Archive for Student Projects Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences Faculty of Forest Sciences Department of Forest Products, Uppsala Sustainable urban development through increased construction in wood? - A study of municipalities’ cooperation in major construction projects in Sweden Hållbar stadsutveckling genom ökad byggnation i trä? - En studie om kommuners samverkan vid större byggprojekt i Sverige Fredrik Sjöström Master Thesis ISSN 1654-1367 No 203 Uppsala 2018 Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences Faculty of Forest Sciences Department of Forest Products, Uppsala Sustainable urban development through increased construction in wood? - A study of municipalities’ cooperation in major construction projects in Sweden Hållbar stadsutveckling genom ökad byggnation i trä? - En studie om kommuners samverkan vid större byggprojekt i Sverige Fredrik Sjöström Keywords: building materials, climate, collaboration, construction pro- ject, multi-family housing, qualitative, semi structured, sustainability, wood construction Master Thesis, 30 ECTS credit Advanced level in Forest Sciences MSc in Forestry 13/18 (EX0833) Supervisor SLU, Department of Forest Products: Anders Lindhagen Examiner SLU, Department of Forest Products: Cecilia Mark-Herbert Abstract The increased awareness of the construction industry's impact on the global climate combined with the current housing shortage in Sweden has contributed to an increasing ask for more wood in construction amongst stakeholders, municipalities and politicians. In order to meet Sweden's climate goals it is necessary that new materials, technologies and working methods continue to evolve. Knowledge, cooperation and communication are described as important elements in order to develop the work towards increased sustainability in the construction sector in Sweden. -

“Our Customers and Locations Are Central in Everything We Do.” Contents 2010 in Brief

Annual Report 2010 “Our customers and locations are central in everything we do.” Contents 2010 in brief Introduction 2010 in brief 1 This is Fabege 2 Message from the CEO 4 Solna The business Strategic focus 6 Stockholm Opportunities and risks 9 Financing 10 The business 12 Property portfolio 20 Hammarby Property valuation 24 Sjöstad Market review 26 Fabege markets Stockholm inner city 28 Solna 30 Concentrated portfolio Hammarby Sjöstad 32 During the year, Fabege sold 54 properties for List of properties 34 SEK 4,350m. Accordingly, Fabege has concluded Responsible enterprise 40 the streamlining of its portfolio to its prioritised submarkets. The concentration has resulted in 98 per Financial reports The 2010 fi nancial year 48 cent of Fabege’s properties now being located within Directors’ report 50 fi ve kilometres of Stockholm’s centre. The divestments have freed capital with which to increase project in- The Group Profi t and loss accounts 56 vestments in the proprietary portfolio, and to acquire Balance sheets 57 properties offering favourable growth potential. Statement of changes in equity 58 Cash fl ow statement 59 Fabege’s heat consumption is The parent company Profi t and loss accounts 60 Balance sheets 60 40 per cent below national Statement of changes in equity 61 Cash fl ow statement 61 average. Fabege’s climate work began in 2002 with a project to replace Notes 62 old oil-fi red boilers with district heating. After that Fabege initiated Corporate governance report 74 a systematic effort to optimize the use of energy, and Fabege cur- Board of Directors 80 rently consumes 40 per cent less heat than the national average. -

Facts About Botkyrka –Context, Character and Demographics (C4i) Förstudie Om Lokalt Unesco-Centrum Med Nationell Bäring Och Brett Partnerskap

Facts about Botkyrka –context, character and demographics (C4i) Förstudie om lokalt Unesco-centrum med nationell bäring och brett partnerskap Post Botkyrka kommun, 147 85 TUMBA | Besök Munkhättevägen 45 | Tel 08-530 610 00 | www.botkyrka.se | Org.nr 212000-2882 | Bankgiro 624-1061 BOTKYRKA KOMMUN Facts about Botkyrka C4i 2 [11] Kommunledningsförvaltningen 2014-05-14 The Botkyrka context and character In 2010, Botkyrka adopted the intercultural strategy – Strategy for an intercultural Botkyrka, with the purpose to create social equality, to open up the life chances of our inhabitants, to combat discrimination, to increase the representation of ethnic and religious minorities at all levels of the municipal organisation, and to increase social cohesion in a sharply segregated municipality (between northern and southern Botkyrka, and between Botkyrka and other municipalities1). At the moment of writing, the strategy, targeted towards both the majority and the minority populations, is on the verge of becoming implemented within all the municipal administrations and the whole municipal system of governance, so it is still to tell how much it will influence and change the current situation in the municipality. Population and demographics Botkyrka is a municipality with many faces. We are the most diverse municipality in Sweden. Between 2010 and 2012 the proportion of inhabitants with a foreign background increased to 55 % overall, and to 65 % among all children and youngsters (aged 0–18 years) in the municipality.2 55 % have origin in some other country (one self or two parents born abroad) and Botkyrka is the third youngest population among all Swedish municipalities.3 Botkyrka has always been a traditionally working-class lower middle-class municipality, but the inflow of inhabitants from different parts of the world during half a decade, makes this fact a little more complex. -

Adaptation to Extreme Heat in Stockholm County, Sweden’

opinion & comment 1 6. Moberg, A., Bergström, H., Ruiz Krisman, J. & 10. Fouillet, A. et al. Int. J. Epidemiol. 37, 309–317 (2008). Cato Institute, 1000 Massachusetts Svanerud, O. Climatic Change 53, 171–212 (2002). 11. Palecki, M. A., Changnon, S. A. & Kunkel, K. E. Ave, NW, Washington DC 20001, USA, Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 82, 1353–1367 (2001). 7. Sutton, R. T. & Dong, B. Nature Geosci. 5, 288–292 (2012). 2 8. Statistics Sweden (accessed 28 October 2013); IntelliWeather, 3008 Cohasset Rd Chico, http://www.scb.se/ 1 1 California 95973, USA. 9. Oudin Åström, D., Forsberg, B., Edvinsson, S. & Rocklöv, J. Paul Knappenberger *, Patrick Michaels 2 Epidemiology 24, 820–829 (2013). and Anthony Watts *e-mail: [email protected] Reply to ‘Adaptation to extreme heat in Stockholm County, Sweden’ Oudin Åström et al. reply — We approach of comparing patterns over 30-year studies cited by Knappenberger et al., thank Knappenberger and colleagues time periods. The observed changes are the socio-economic development, epidemiological for their interest in our research1. Their result of natural processes, including regional transitions and health system changes were correspondence expresses two concerns: a climate variability, and anthropogenic and continue to be the main drivers of possible bias in the temperature data2 and influences, including urbanization3. changes in population sensitivity — not appropriate consideration of adaptation Our method of comparing the climate explicit, planned actions to prepare for to extreme-heat events over the century. during two 30-year periods is valid for climate change impacts. These changes also To clarify, we estimated the impacts of any two periods. -

Case Study Sweden

TSFEPS Project Changing Family Structures and Social Policy: Child Care Services in Europe and Social Cohesion Case Study Sweden Victor Pestoff Peter Strandbrink with the assistance of Joachim Andersson, Nina Seger and Johan Vamstad 2 Small children in a big system. A case study of childcare in Stockholm and Östersund th Swedish case study for the 5 framework research EU-project TSFEPS Final revised version, March 29 2004 * * * * * Victor Pestoff Peter Strandbrink Department of political science Department of political science Mid-Sweden university Södertörn University College SE-831 25 Östersund, SWEDEN SE-141 89 Huddinge, SWEDEN email: [email protected] email: [email protected] phone: +46-63-165763 phone: +46-8-6084581 Research assistant, Östersund Research assistants, Stockholm Nina Seger Joachim Andersson Johan Vamstad 3 Contents 1 Introduction 5 2 Methodology 10 3 Empirical analysis 20 3.1 Stockholm: city-wide level 20 3.2 Stockholm: the Maria-Gamla Stan ward 38 3.2.1 User experience of municipal childcare in Maria-Gamla Stan 47 3.2.2 User experience of co-operative childcare in Maria-Gamla Stan 50 3.2.3 User experience of corporate childcare in Maria-Gamla Stan 52 3.3 Stockholm: the Skärholmen ward 56 3.3.1 Local managerial level in municipal childcare in Skärholmen 63 3.3.2 User experience of municipal childcare in Skärholmen 68 3.3.3 Local managerial level in co-operative childcare in Skärholmen 70 3.3.4 User experience of co-operative childcare in Skärholmen 77 3.3.5 Local managerial level in for-profit childcare in Skärholmen 79 3.3.6 User experience of for-profit childcare in Skärholmen 85 3.4 Stockholm: the Bromma ward 87 3.5 Östersund 92 4 Conclusion: social cohesion and Swedish childcare 100 References 107 Interviews 107 Tables Table 1. -

View Annual Report

“ Our customers and locations are central in everything we do.” Annual Report 2009Ä P L Ä Ä G E N Contents Highlights of 2009 Introduction 2009 in brief 1 This is Fabege 2 Message from the CEO 4 Financial highlights The business Strategic focus 6 • Earnings after tax for the year increased by SEK The business 10 936m from SEK –511m to SEK +425m. The lower Property portfolio 15 net interest expenses added SEK +244m and re- Market valuation 18 duced negative value adjustments brought another The investment market 19 Market review 20 SEK +1,753m, while the effective tax rate increased Fabege markets by SEK – 1,084m. Stockholm inner city 23 • Earnings before tax were SEK 561m (–1,285) Solna 24 in Property Management and SEK 119m (–55) in Hammarby sjöstad and Other markets 27 Improvement Projects. List of properties 28 • The profit from property management increased to Responsible enterprise 34 SEK 838m (568) while rental income decreased Financial reports Directors’ report 42 to SEK 2,194m (2,214) due to sales of properties. The Group Profit and loss account 48 • The surplus ratio increased to 67 per cent (65%). Balance sheet 49 Statement of changes in equity 50 • Earnings per share were SEK 2.59 (–3.07) and Cash flow statement 51 equity per share was SEK 61 (60). The parent company Profit and loss account 52 • The Board proposes a dividend of SEK 2.00 per Balance sheet 52 share (2.00). Statement of changes in equity 53 Statement of Cash flows 53 Notes 54 Signing of the Annual Report 66 www.fabege.se Audit report 67 More information about Fabege and our operations Corporate governance report 68 is available on the Group’s website. -

Health Systems in Transition : Sweden

Health Systems in Transition Vol. 14 No. 5 2012 Sweden Health system review Anders Anell Anna H Glenngård Sherry Merkur Sherry Merkur (Editor) and Sarah Thomson were responsible for this HiT Editorial Board Editor in chief Elias Mossialos, London School of Economics and Political Science, United Kingdom Series editors Reinhard Busse, Berlin University of Technology, Germany Josep Figueras, European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies Martin McKee, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, United Kingdom Richard Saltman, Emory University, United States Editorial team Sara Allin, University of Toronto, Canada Jonathan Cylus, European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies Matthew Gaskins, Berlin University of Technology, Germany Cristina Hernández-Quevedo, European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies Marina Karanikolos, European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies Anna Maresso, European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies David McDaid, European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies Sherry Merkur, European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies Philipa Mladovsky, European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies Dimitra Panteli, Berlin University of Technology, Germany Bernd Rechel, European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies Erica Richardson, European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies Anna Sagan, European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies Sarah Thomson, European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies Ewout van Ginneken, Berlin University of Technology, Germany International -

Interim Report Q3 2017

STRONG OPERATING PROFIT IN A CAUTIOUS MARKET INTERIM REPORT Q3 2017 Mattias Roos, President & CEO Casper Tamm, Director of Finance Stockholm, November 15, 2017 Q3 HIGHLIGHTS • An eventful quarter – Strategic JV with Partners Group, project valued at 7.6 SEKbn • High interest in our projects – 1,100 sales starts to mid-Nov 2017 – 27.7% more units sold in first 9 months – 97.1% sales rate in projects in production end-Q3 • Solid financial profile, well above financial targets – Debt/equity ratio of 57.8% • Highly equipped for continued growth and earnings performance ACQUIRED BUILDING RIGHTS AS PER NOVEMBER 15, 2017 Building Municipality Acquired rights Täby Turf 180 Täby Q1 Täby Market 90 Täby Q1 Bromma Boardwalk 260 Stockholm Q1 East Side Spånga 250 Stockholm Q2 Akalla City 175 Stockholm Q2 Spånga Studios 60 Stockholm Q2 Ritsalen, Rotebro 150 Sollentuna Q3 Riddarplatsen, Jakobsberg 370 Järfälla Q3 Hägersten 250 Stockholm Q4 Managed entirely by SSM Municipality Off market SOLID PORTFOLIO PROVIDES CONFIDENCE IN LONG-TERM STABLE GROWTH No. of building rights 58% OF PORTFOLIO IN STOCKHOLM MUNICIPALITY Jakobsberg Sundbyberg Sollentuna Täby Solna 6,677 Stockholm Nacka Portfolio split by municipality in Greater Stockholm as per November 15, 2017. Bromma Boardwalk STRONG PIPELINE & PLATFORM WITH POTENTIAL FOR FURTHER GROWTH No. of building rights and units in construction Bulding rights in construction phase Building rights in planning phase % sold apartments under construction 8,000 100% 80% 6,000 60% 4,000 5,013 40% 2,000 20% 1,414 0 0% dec -

Regional District Heating in Stockholm

Dick Magnusson, PhD Student Department of Thematic Studies: Technology and Social Change Linköping University, Sweden [email protected] +46(0)13-282503 Planning for a sustainable city region? - Regional district heating in Stockholm Abstract District heating is an old and established energy system in Sweden, accounting for 9 % of the national energy balance. The systems have traditionally been built, planned and managed by the municipalities and over the years the district heating systems in Stockholm have grown into each other and later been interconnected. This have led to that there today are three large systems with eight energy companies and the system can be considered a regional system. The strategy to create a regional system has existed for a long time from regional planning authorities. However, since the municipalities have planning monopoly the regional planning is weak. The overall aim for this study is to analyse the planning and development of an important regional energy system, the district heating system in Stockholm, to understand how the municipal and regional planning have related to each other. The study is conducted through studying municipal and regional plans in Stockholm’s county between 1978 and 2010. The results show that district heating has been considered important all along and that a regional, or rather inter-municipal, perspective has existed throughout the period, although with large differences between different municipalities. Regional strategies for an interconnected system and combined heat and power plants have been realised gradually and district heating have throughout the period been considered important for different environmental reasons. 1 Introduction In Sweden, district heating (DH) is an important part of the energy system, accounting for approximately 55 TWh of the annual energy supply of 612 TWh, and a 55% share of the total heating market.1 In some cities, the district heating systems are old, well-established, and have developed into regional energy systems, with Stockholm being the foremost example. -

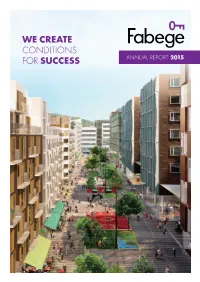

WE CREATE CONDITIONS for SUCCESS ANNUAL REPORT 2015 This Document Is a Translation of the Original, Published in Swedish

WE CREATE CONDITIONS FOR SUCCESS ANNUAL REPORT 2015 This document is a translation of the original, published in Swedish. In cases of any discrepancies between the Swedish and English version, or in any other context, the Swedish original shall have precedence. FABEGE CREATES CONDITIONS FOR SUCCESS INTRODUCTION This is Fabege 1 Highlights of the year 2 Message from the CEO 4 Business concept, strategy and value chain 6 Business model 8 Targets 10 OPERATIONS Overview of operations 12 Property Management 14 Property Development 18 ATTRACTIVE Transactions 22 Valuation 24 LOCATIONS Market overview 26 Fabege’s properties are located in a Stockholm inner city 28 number of the fastest growing areas in Hammarby Sjöstad 30 Stockholm all of which offer excellent Solna 32 Arenastaden 34 transport facilities. Sustainability work 36 Stakeholder dialogue 38 Material issues 39 Employees 40 Business ethics 44 Social involvement 46 CONCENTRATED MODERN Awards and nominations 47 PORTFOLIO PROPERTIES FINANCIAL Directors’ Report 49 Concentrated portfolios facilitate market Modern, sustainable offi ces REPORTING Risks and opportunities 56 awareness and provide opportunities to in attractive locations in terms of Group meet customer requirements. This means the transport links and good surrounding Statement of comprehensive income 63 Statement of fi nancial position 64 company is well placed to infl uence the services are increasingly in demand. Statement of changes in equity 65 development of entire city districts and Fabege offers modern, fl exible and Statement