The Erratic Cinema of Paul Thomas Anderson by Matthew Rodrigues, BA

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kvarterakademisk

kvarter Volume 18. Spring 2019 • on the web akademiskacademic quarter From Wander to Wonder Walking – and “Walking-With” – in Terrence Malick’s Contemplative Cinema Martin P. Rossouw has recently been appointed as Head of the Department Art History and Image Studies – University of the Free State, South Africa – where he lectures in the Programme in Film and Visual Media. His latest publications appear in Short Film Studies, Image & Text, and New Review of Film and Television Studies. Abstract This essay considers the prominent role of acts and gestures of walking – a persistent, though critically neglected motif – in Terrence Malick’s cinema. In recognition of many intimate connections between walking and contemplation, I argue that Malick’s particular staging of walking characters, always in harmony with the camera’s own “walks”, comprises a key source for the “contemplative” effects that especially philo- sophical commentators like to attribute to his style. Achieving such effects, however, requires that viewers be sufficiently- en gaged by the walking presented on-screen. Accordingly, Mal- ick’s films do not fixate on single, extended episodes of walk- ing, as one would find in Slow Cinema. They instead strive to enact an experience of walking that induces in viewers a par- ticular sense of “walking-with”. In this regard, I examine Mal- ick’s continual reliance on two strategies: (a) Steadicam fol- lowing-shots of wandering figures, which involve viewers in their motion of walking; and (b) a strict avoidance of long takes in favor of cadenced montage, which invites viewers into a reflective rhythm of walking. Volume 18 41 From Wander to Wonder kvarter Martin P. -

Fiona Apple, Mit Gabriela Krapf

Jazz Collection: Fiona Apple, mit Gabriela Krapf Dienstag, 10. Oktober 2017, 21.00 - 22.00 Uhr Samstag, 14. Oktober 2017, 17.06 - 18.30 Uhr (Zweitsendung mit Bonustracks) Fiona Apple – Das Leben singen Das Werk der New Yorker Sängerin, Pianistin und Songschreiberin Fiona Apple ist mit vier Alben zwar schmal, aber es ist gewichtig. Mit 18 erhielt sie für ihr Debut einen Grammy, 22 Jahre und etwa 100 Songs später ist sie zur Ikone geworden. Irgendwie überfordert Fiona Apple alle mit ihrer Kunst, die Plattenlabels, ihre Zuhörerinnen und Zuhörer und oft genug auch sich selber. Denn Kompromisse sind nicht vorgesehen: Fiona Apple macht ihre eigene Person, ihre Verletzlichkeit, ihre psychischen Probleme und die Verwerfungen ihrer Biographie radikal zum Thema. Die Sängerin und Pianistin Gabriela Krapf ist eine grosse Bewunderin von Fiona Apple. Gemeinsam mit Annina Salis diskutiert sie ihr Werk, welches Musik und Poesie untrennbar miteinander verschmelzen lässt. Gast: Gabriela Krapf Redaktion: Beat Blaser Moderation: Annina Salis Fiona Apple: Tidal Label: Columbia Track 02: Sullen Girl Track 04: Criminal Fiona Apple: When the Pawn… Label: Epic, Clean State Track 01: On the Bound Track 05: Paper Bag Fiona Apple: Extraordinary Machine Label: Epic Track 01: Extraordinary Machine Track 05: Tymps (The Sick in the Head Song) Fiona Apple Youtube Track: Tymps (The Sick in the Head Song) Fiona Apple: The Idler Wheel Label: Epic Track 09: Anything We Want Track 10: Hot Knife Bonustracks – (nur am Samstag, 14.10.2017) Gabriela Krapf and Horns: The Great Unknown Label: Eigenvertrieb Track 03: But Then You Called Andrew Bird feat. Fiona Apple: Are You Serious Label: Decca Track 06: Left Handed Kisses Fiona Apple feat. -

Philosophy Physics Media and Film Studies

MA*E299*63 This Exploration Term project will examine the intimate relationship Number Theory between independent cinema and film festivals, with a focus on the Doug Riley Sundance Film Festival in Park City, Utah. Film festivals have been central Prerequisites: MA 231 (for mathematical maturity) to international and independent cinema since the 1930s. Sundance Open To: All Students is the largest independent film festival in the United States and has Grading System: Letter launched the careers of filmmakers like Paul Thomas Anderson, Kevin Max. Enrollment: 16 Smith, and Quentin Tarantino. During this project, students will study Meeting Times: M W Th 10:00 am–12:00 pm, 1:30 pm–3:30 pm the history of film festivals and the ways in which they have influenced the landscape of contemporary cinema. The class will then travel to the Number Theory is the study of relationships and patterns among the Sundance Film Festival for the last two weeks of the term to attend film integers and is one of the oldest sub-disciplines of mathematics, tracing screenings, panels, workshops and to interact with film producers and its roots back to Euclid’s Elements. Surprisingly, some of the ideas distributers. explored then have repercussions today with algorithms that allow Estimated Student Fees: $3200 secure commerce on the internet. In this project we will explore some number theoretic concepts, mostly based on modular arithmetic, and PHILOSOPHY build to the RSA public-key encryption algorithm and the quadratic sieve factoring algorithm. Mornings will be spent in lecture introducing ideas. PL*E299*66 Afternoons will be spent on group work and student presentations, with Philosophy and Film some computational work as well. -

A Wishy-Washy, Sort-Of-Feeling: Episodes in the History of the Wishy-Washy Aesthetic

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 8-22-2014 12:00 AM A Wishy-Washy, Sort-of-Feeling: Episodes in the History of the Wishy-Washy Aesthetic Amy Gaizauskas The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Christine Sprengler The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Art History A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Master of Arts © Amy Gaizauskas 2014 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Recommended Citation Gaizauskas, Amy, "A Wishy-Washy, Sort-of-Feeling: Episodes in the History of the Wishy-Washy Aesthetic" (2014). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 2332. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/2332 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A WISHY-WASHY, SORT-OF FEELING: EPISODES IN THE HISTORY OF THE WISHY-WASHY AESTHETIC Thesis Format: Monograph by Amy Gaizauskas Graduate Program in Art History A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Art The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada © Amy Gaizauskas 2014 Abstract Following Sianne Ngai’s Our Aesthetic Categories (2012), this thesis studies the wishy- washy as an aesthetic category. Consisting of three art world and visual culture case studies, this thesis reveals the surprising strength that lies behind the wishy-washy’s weak veneer. -

Crazy Narrative in Film. Analysing Alejandro González Iñárritu's Film

Case study – media image CRAZY NARRATIVE IN FILM. ANALYSING ALEJANDRO GONZÁLEZ IÑÁRRITU’S FILM NARRATIVE TECHNIQUE Antoaneta MIHOC1 1. M.A., independent researcher, Germany. Corresponding author: [email protected] Abstract Regarding films, many critics have expressed their dissatisfaction with narrative and its Non-linear film narrative breaks the mainstream linearity. While the linear film narrative limits conventions of narrative structure and deceives the audience’s expectations. Alejandro González Iñárritu is the viewer’s participation in the film as the one of the directors that have adopted the fragmentary narrative gives no control to the public, the narration for his films, as a means of experimentation, postmodernist one breaks the mainstream con- creating a narrative puzzle that has to be reassembled by the spectators. His films could be included in the category ventions of narrative structure and destroys the of what has been called ‘hyperlink cinema.’ In hyperlink audience’s expectations in order to create a work cinema the action resides in separate stories, but a in which a less-recognizable internal logic forms connection or influence between those disparate stories is the film’s means of expression. gradually revealed to the audience. This paper will analyse the non-linear narrative technique used by the In the Story of the Lost Reflection, Paul Coates Mexican film director Alejandro González Iñárritu in his states that, trilogy: Amores perros1 , 21 Grams2 and Babel3 . Film emerges from the Trojan horse of Keywords: Non-linear Film Narrative, Hyperlink Cinema, Postmodernism. melodrama and reveals its true identity as the art form of a post-individual society. -

The Soraya Joins Martha Graham Dance Company and Wild up for the June 19 World Premiere of a Digital Dance Creation

The Soraya Joins Martha Graham Dance Company and Wild Up for the June 19 World Premiere of a Digital Dance Creation Immediate Tragedy Inspired by Martha Graham’s lost solo from 1937, this reimagined version will feature 14 dancers and include new music composed by Wild Up’s Christopher Rountree (New York, NY), May 28, 2020—The ongoing collaboration by three major arts organizations— Martha Graham Dance Company, the Los Angeles-based Wild Up music collective, and The Soraya—will continue June 19 with the premiere of a digital dance inspired by archival remnants of Martha Graham’s Immediate Tragedy, a solo she created in 1937 in response to the Spanish Civil War. Graham created the solo in collaboration with composer Henry Cowell, but it was never filmed and has been considered lost for decades. Drawing on the common experience of today’s immediate tragedy – the global pandemic -- the 22 artists creating the project are collaborating from locations across the U.S. and Europe using a variety of technologies to coordinate movement, music, and digital design. The new digital Immediate Tragedy, commissioned by The Soraya, will premiere online Friday, June 19 at 4pm (Pacific)/7pm (EST) during Fridays at 4 on The Soraya Facebook page, and Saturday, June 20 at 11:30am/2:30pm at the Martha Matinee on the Graham Company’s YouTube Channel. In its new iteration, Immediate Tragedy will feature 14 dancers and 6 musicians each recorded from the safety of their homes. Martha Graham Dance Company’s Artistic Director Janet Eilber, in consultation with Rountree and The Soraya’s Executive Director, Thor Steingraber, suggested the long-distance creative process inspired by a cache of recently rediscovered materials—over 30 photos, musical notations, letters and reviews all relating to the 1937 solo. -

Scene and Heard: a Profile of Laura Colella

Scene and Heard: A Profile of Laura Colella She sits quietly in a coffee shop, waiting. She is of small stature, and fine boned. She has striking eyes and a beautiful face, one that easily could be in front of the camera. Providence born and raised, no one she knew ever talked about becoming a filmmaker. She is definitely under the radar – but is soaring very high. This is Laura Colella. In her 44 years, she has managed to impress some very important people in the film world. One of those folks is Paul Thomas Anderson – the same Paul Thomas Anderson who wrote and directed The Master, There Will Be Blood, Boogie Nights and my personal favorite (and I believe his), Magnolia. Last February, he hosted a screening of her film Breakfast with Curtis in LA, and held a lengthy Q & A session afterward. In the same month, at the Independent Spirit Awards, the film was nominated for the John Cassavetes Award for Best Feature made for under $500,000, and won a $50,000 distribution grant from Jameson. Her love of film started early. She grew up heavily involved in theater, was in a few productions at Trinity Rep, and worked there as a production assistant. “My first year in college at Harvard, my boyfriend took me to the end-of-year film screenings at RISD, which opened up that world of possibility for me. I discovered the excellent film department at Harvard, which centered on 16MM production, became totally immersed in it, and never looked back.” Laura now has three features under her belt – Tax Day, her first, for which she received a special equipment grant through the Sundance Institute, portrays two women on their way to the post office on that dreaded day, April 15. -

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center ROOD, RICHARD #1117 September 1989 - June 1997 Biography: Richard Roud ( 1929-1989), as director of both the New York and London Film Festivals, was responsible for both discovering and introducing to a wider audience many of the important directors of the latter half th of the 20 - century (many of whom he knew personally) including Bernardo Bertolucci, Robert Bresson, Luis Buiiuel, R.W. Fassbinder, Jean-Luc Godard, Werner Herzog, Terry Malick, Ermanno Ohni, Jacques Rivette and Martin Scorsese. He was an author of books on Jean-Marie Straub, Jean-Luc Godard, Max Ophuls, and Henri Langlois, as well as the editor of CINEMA: A CRITICAL DICTIONARY. In addition, Mr. Roud wrote extensive criticism on film, the theater and other visual arts for The Manchester Guardian and Sight and Sound and was an occasional contributor to many other publications. At his death he was working on an authorized biography of Fran9ois Truffaut and a book on New Wave film. Richard Roud was a Fulbright recipient and a Chevalier in the Legion of Honor. Scope and contents: The Roud Collection (9 Paige boxes, 2 Manuscript boxes and 3 Packages) consists primarily of book research, articles by RR and printed matter related to the New York Film Festival and prominent directors. Material on Jean-Luc Godard, Francois Truffaut and Henri Langlois is particularly extensive. Though considerably smaller, the Correspondence file contains personal letters from many important directors (see List ofNotable Correspondents). The Photographs file contains an eclectic group of movie stills. -

Steve Mcqueen – Filmaker and Director

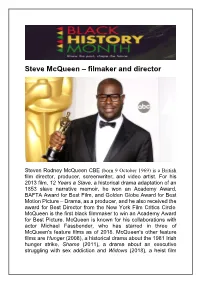

Steve McQueen – filmaker and director Steven Rodney McQueen CBE (born 9 October 1969) is a British film director, producer, screenwriter, and video artist. For his 2013 film, 12 Years a Slave, a historical drama adaptation of an 1853 slave narrative memoir, he won an Academy Award, BAFTA Award for Best Film, and Golden Globe Award for Best Motion Picture – Drama, as a producer, and he also received the award for Best Director from the New York Film Critics Circle. McQueen is the first black filmmaker to win an Academy Award for Best Picture. McQueen is known for his collaborations with actor Michael Fassbender, who has starred in three of McQueen's feature films as of 2018. McQueen's other feature films are Hunger (2008), a historical drama about the 1981 Irish hunger strike, Shame (2011), a drama about an executive struggling with sex addiction and Widows (2018), a heist film about a group of women who vow to finish the job when their husbands die attempting to do so. McQueen was born in London and is of Grenadianand Trinidadian descent. He grew up in Hanwell, West London and went to Drayton Manor High School. In a 2014 interview, McQueen stated that he had a very bad experience in school, where he had been placed into a class for students believed best suited "for manual labour, more plumbers and builders, stuff like that." Later, the new head of the school would admit that there had been "institutional" racism at the time. McQueen added that he was dyslexic and had to wear an eyepatch due to a lazy eye, and reflected this may be why he was "put to one side very quickly". -

Anthropocenema: Cinema in the Age of Mass Extinctions 2016

Repositorium für die Medienwissenschaft Selmin Kara Anthropocenema: Cinema in the Age of Mass Extinctions 2016 https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/13476 Veröffentlichungsversion / published version Sammelbandbeitrag / collection article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Kara, Selmin: Anthropocenema: Cinema in the Age of Mass Extinctions. In: Shane Denson, Julia Leyda (Hg.): Post-Cinema. Theorizing 21st-Century Film. Falmer: REFRAME Books 2016, S. 750– 784. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/13476. Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Creative Commons - This document is made available under a creative commons - Namensnennung - Nicht kommerziell - Keine Bearbeitungen 4.0/ Attribution - Non Commercial - No Derivatives 4.0/ License. For Lizenz zur Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu dieser Lizenz more information see: finden Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ 6.2 Anthropocenema: Cinema in the Age of Mass Extinctions BY SELMIN KARA Alfonso Cuarón’s sci-fi thriller Gravity (2013) introduced to the big screen a quintessentially 21st-century villain: space debris. The spectacle of high- velocity 3D detritus raging past terror-struck, puny-looking astronauts stranded in space turned the Earth’s orbit into not only a site of horror but also a wasteland of hyperobjects,[1] with discarded electronics and satellite parts threatening everything that lies in the path of their ballistic whirl (see Figure 1). While the film made no environmental commentary on the long-term effect of space debris on communication systems or the broader ecological problem of long-lasting waste materials, it nevertheless projected a harrowing vision of technological breakdown, which found a thrilling articulation in the projectile aesthetics of stereoscopic cinema. -

The Terminator by John Wills

The Terminator By John Wills “The Terminator” is a cult time-travel story pitting hu- mans against machines. Authored and directed by James Cameron, the movie features Arnold Schwarzenegger, Linda Hamilton and Michael Biehn in leading roles. It launched Cameron as a major film di- rector, and, along with “Conan the Barbarian” (1982), established Schwarzenegger as a box office star. James Cameron directed his first movie “Xenogenesis” in 1978. A 12-minute long, $20,000 picture, “Xenogenesis” depicted a young man and woman trapped in a spaceship dominated by power- ful and hostile robots. It introduced what would be- come enduring Cameron themes: space exploration, machine sentience and epic scale. In the early 1980s, Cameron worked with Roger Corman on a number of film projects, assisting with special effects and the design of sets, before directing “Piranha II” (1981) as his debut feature. Cameron then turned to writing a science fiction movie script based around a cyborg from 2029AD travelling through time to con- Artwork from the cover of the film’s DVD release by MGM temporary Los Angeles to kill a waitress whose as Home Entertainment. The Library of Congress Collection. yet unborn son is destined to lead a resistance movement against a future cyborg army. With the input of friend Bill Wisher along with producer Gale weeks. However, critical reception hinted at longer- Anne Hurd (Hurd and Cameron had both worked for lasting appeal. “Variety” enthused over the picture: Roger Corman), Cameron finished a draft script in “a blazing, cinematic comic book, full of virtuoso May 1982. After some trouble finding industry back- moviemaking, terrific momentum, solid performances ers, Orion agreed to distribute the picture with and a compelling story.” Janet Maslin for the “New Hemdale Pictures financing it. -

Har Sinai Temple Bulletin

HAR SINAI TEMPLE BULLETIN FOUNDED 1857 TammuzlAvlElul5754 Vol. CXXXVII No.1 lIAR SINAI INSTALLS 1994-1995 Summer services began in late June and will continue through July EXECUTIVE BOARD & and August until the beginning of the High Holy Days. Summer ---- BOARD OF TRUSTEES ---- services begin at 8:00 P.M. and are held in Har Sinai's air-conditioned Social Hall. Dress is casual and congregants are encouraged to participate in the services. If you are interested in delivering a Dvar Torah or a short sermon or helping to lead the service, contact the rabbi or the cantor. Pictured above at the June 20th Annual Meeting is the 1994-95 Har Sinai Executive Board: Front, left to right, are Ariel Perelmuter, Dr. Don Millner, • Lauren Schor, Roberta Frank, and in back are Dr. Howard Welt, Nancy Frost, Simon Kimmelman, and Dr. Steve Sussman. Photo by Don Lowing New Executive Board Members Howard Welt, Treasurer A native of New York City, Howard has lived in Yardley for the past twenty two years. He is a Phi Beta Kappa graduate of Cornell University and graduated from the New York University School of Medicine where he was elected to the Alpha Omega Alpha Medical Honor Society. Howard is a senior partner and Secretary of Radiology Affiliates of Central New Jersey, P.A. He has been the Chairman of the Department of Radiology of the Robert Wood Johnson University Hospital at Hamilton for the past 14 years. He is also an Attending Radiologist on the staffs of St. Francis Medical Center, St. Mary Hospital in Langhorne, and St.