Seething Wells and the People Who Lived and Worked There

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spring 2013 Published Quarterly Since Spring 1970

81852_ISFC_SPRING inside Cover 2005 28/02/2013 11:54 Page 1 A centre dedicated to holistic & complementary healthcare for all We offer a range of therapies that will effectively treat a variety of problems. &% $#"!" #" &% ! &% $!% &% ! ! &% %# "% &% %% &% !%% &% #! &% % "%! &% &% " &% &% % # &% %% % &% !% % &% !" % Tel: 020 8941 2846 www.ClinicofNaturalMedicine.co.uk Above Kent Chemist, on 2nd Floor, 104 Walton Road, East Molesey, Surrey KT8 0DL 81852_TDT_N_Thames Ditton SPRING 2005 04/03/2013 14:37 Page 3 The Magazine of the Thames Ditton and Weston Green Residents’ Association Spring 2013 Published quarterly since Spring 1970 Editor In this Issue: Keith Evetts 6 Church Walk Thames Ditton KT7 0NW News from the Residents’ Association ………………… 7 020 8398 7320 [email protected] New Development – you decide where ………………… 17 Magazine Design Putting it to the Test (TDJS science lab) ………………… 23 Guy Holman 24 Angel Road, Thames Ditton Your Residents’ Association in Action ………………… 24 020 8398 1770 An Active County Councillor (Peter Hickman) ………… 27 Distribution Manager David Youd Admiral George Robert Lambert ………………………… 29 6 Riversdale Road, Thames Ditton KT7 0QL 020 8398 3216 Music for Spring at the Vera Fletcher Hall ……………… 35 Advertisement Manager Theatre in the Village (Noticeboard) …………………… 39 Verity Park 20 Portsmouth Avenue Spring Crossword………………………………………… 41 Thames Ditton KT7 0RT 020 8398 5926 Solution to Winter Crossword …………………………… 43 Contributors You are welcome to submit articles Services, Groups, Clubs and Societies…………………… 44 or images. Please contact the Editor well in advance of the next deadline on 8 May. The Association’s Web Site and Forum ………………… 46 Advertisers Thames Ditton Today is delivered Cover photo: Easter bunnies in Bushy Park to an influential 4000 households – photo by professional photographer, throughout Thames Ditton and resident David Spink (07966 238 341) Weston Green. -

PORTSMOUTH ROAD the Thames Landscape Strategy Review 1 9 7

REACH 03 PORTSMOUTH ROAD The Thames Landscape Strategy Review 1 9 7 Landscape Character Reach No 3 PORTSMOUTH ROAD 4.03.1 Overview 1994-2012 • Construction of new cycle/footpath along Barge Walk and the opening of views across the river • Habitat enhancement in the Home Park including restoration of acid grassland • Long-running planning process for the Seething Wells fi lter beds • TLS initiative to restore the historic Home Park water meadows. • RBKuT Kingston Town Centre Area Action Plan K+20 • RBK and TLS Integrated Moorings Business Plan • Management of riverside vegetation along the Barge Walk • Restoration of the Long Water Avenue in 2006 LANDSCAPE CHARACTER 4.03.2 The Portsmouth Road Reach runs north from Seething Wells up to Kingston. The reach has a character of wide open grassland, interrupted only by trees, park and water-works walls and the Portsmouth Road blocks of fl ats. Hampton Court Park extends over the entire Middlesex side right up to Hampton Wick, while the Surrey bank divides between the former Water Works and the Queen’s Promenade. The Portsmouth Road follows the river the length of the reach on the Surrey side. This is one of the only sections of the upstream London Thames where a road has been built alongside the river. The busy road and associated linear developments make a harsh contrast with the rhythm of parkland and historic town waterfronts which characterise the rest of the river. Portsmouth Road 4.03.3 Hampton Court Park is held in the circling sweep of the Thames, as its fl ow curves from south to north. -

Buses from Kingston Hospital (Norbiton)

Buses from Kingston Hospital (Norbiton) 24 hour 85 service Putney Bridge Queen’s Road 371 Station Approach Richmond Hill Richmond Richmond Richmond North Sheen Putney Bus Station George Street Manor Circus Roehampton Putney Heath Petersham Alton Road Green Man The Dysarts RICHMOND River Thames Sandy Lane K3 PUTNEY Roehampton Vale ASDA Kingston Vale Streatham Streatham Hill Ashburnham Road 24 hour Robin Hood Way Shops St Leonard's Church Telford Avenue 57 service Mitcham Lane River Thames K5 HAM Kingston Hill Southcroft Road Streatham Hill Clapham Ham Kingston University Dukes Avenue Bowness Crescent Park Atkins Road Kingston Hill Tooting Broadway Cardinal Avenue Tudor Kingston Lodge STREATHAM Latchmere Lane Drive Colliers Wood Q U E E Schools N S D R Canbury A O Merton Abbey K5 O A P R ES D Wych Elm A D NC OA RI ǰ R R R P AD Morden MA O G AG K R Hail & Ride section D H A Coombe Wood G ǯ R U RO L O South Wimbledon BO S Golf Course Kingston A Leask W D D R ǫ O WIMBLEDON Hail & Ride ROA O Centre section MORDEN Cromwell Road LE CK A R VIL I D N Ǵ W L T Ǯ GLE S L Merton Park Bus Station N I H RU H W Wimbledon B Kingston Y Circle Gardens O C D N OA R L R O L Hospital ǭ N O I TO T V F EL dz S E A T G W R O N D O I T Worple Road Kingston Road N K L O KINGSTON ǵ S E R N Nelson Hospital Y O C A A L D TE V O Raynes Park Kingston Norbiton GA S R R E Coombe Lane NO E M A N Eden Street Church O Ǫ Wimbledon A U West D E ǥ Ƕ Chase G AD O BE RO R COOM Ǩ Coombe Lane D ǽ D O A R N Ǥ D Kingston By-Pass 371 O O ǧ OA A C Ǽ Route finder R Ƿ R O D C L B L N H -

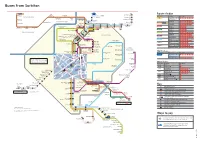

Buses from Surbiton

Buses from Surbiton 281 N65 K3 Hounslow Teddington continues to Roehampton Vale Fulwell Ealing Broadway Bus Station Stanley Road Lock ASDA Richmond Robin Hood Way HOUNSLOW Broad Street Hampton Shops for Teddington Wick Hounslow Wood Street Bowness Crescent Treaty Centre for Bentall Centre Kingsgate Pertersham Road The Dysart Kingston Hill Twickenham Green TEDDINGTON Hounslow Kingston Cromwell Road London Road Kingston Kingston University Bus Station Tifn School Norbiton Hospital High Street Guildhall/Rose Theatre Kingston Hill Kingston High Street George Road London Road Whitton Twickenham Twickenham East Lane 71 406 418 K2 Admiral Nelson Stadium Norbiton Church 465 K1 K4 Buses from Surbiton Kingston Hall Road TWICKENHAM Eden Penrhyn Road Kingston Crown Court Street /Kingston College KINGSTON 281 Penrhyn Road Kingston University/County Hall Brook Street N65 K3 Penrhyn Road Kingston University continues to Hounslow Fulwell Teddington Roehampton Vale Bus Station Ealing Broadway ASDA Stanley Road Surbiton RoadLock HOUNSLOW Milestone House Richmond Robin Hood Way Broad Street Hampton Faireld South Surbiton Hill Park Shops for Teddington Wick Villiers Road Pembroke Avenue Hounslow Wood Street Bowness Crescent Treaty Centre PertershamDawson Road Surbiton Road for Bentall Centre Kingsgate Road The DysartVilliers Road TEDDINGTONPenrhyn Road Surbiton Road Athelstan Park Kingston Hill Twickenham Green Maplehurst Close Raeburn Avenue Kingston University Hounslow Kingston Cromwell Road London Road Berrylands The RoystonsKingston Bus StationVilliers -

Slow Sand Filtration

From London Soup to clear and palatable v1.0 From London Soup and “chimera dire” to clear, bright, agreeable and palatable By Simon Tyrrell Slow sand filtration – a quest for cleaner water How two enterprising water companies extended and improved the public supply of clean water Why they chose to move to Seething Wells to do it What’s known about what happened, and when What everything did, and why … … and the physical legacy it all left behind Slow sand filtration 1804: First known instance of water filtration John Gibbs‟ bleachery in Paisley, Scotland experimental slow sand filter surplus treated water sold to the public at halfpenny a gallon Greenock 1827 (Quest for pure water, Baker, 1949) 1 From London Soup to clear and palatable v1.0 Existence of pathogenic bacteria was unknown. Slow sand filtration considered a mechanical means of removing suspended solids. James Simpson also tramped 2000 miles in 1827 to inspect existing filters (in Scotland and North and East England) and experimented with a small scale plant in 1828. 1829: slow sand filtration first adopted for public water supply by James Simpson at the Chelsea Water Company in Pimlico and subsequently used by both Lambeth and Chelsea at Seething Wells. The materies morbi that Snow suggested transmitted infection from previous cholera cases through water could be removed, with other solids, through filtration avoided by drawing supply upstream of sewer discharge 1858: Regular examination of water supplies started in London and included chemical analysis. 1885 -

Download: Inspector's Report on the Core Strategy

Appendix A – Changes proposed by the Council to make the Core Strategy sound These Council Changes (CC) are proposed by the Council in response to points raised and suggestions discussed during the Examination and they are required to make the plan sound. The changes below are expressed either in the conventional form of strikethrough for deletions and underlining for additions of text, or by specifying the change in words in italics. The page numbers and paragraph numbering below refer to the submission CS, and do not take account of the deletion or addition of text. Policy / No. Page Change Paragraph CC3 7 2.5 New sentence at the end: Figure 1 shows the structure of the Core Strategy guidance and how it links to the Kingston Plan and to the mechanisms to deliver the strategy. Insert Figure 1 as shown in the revised Figures. CC1 14 3.28 The Core Strategy must take account of and follow national planning policy, as set out in Planning Policy Statements (PPSs) and Planning Policy Guidance Notes (PPGs), or any future national guidance prepared by the government. CC4 20-21 Objectives Insert amended list of Objectives as shown in Schedule 1. CC3 20 4.3 Add to the end: Further guidance on how these objectives will be applied locally is set out in paragraphs 4.4 and 4.5 and regard should be given to these paragraphs when applying these objectives. The policies and guidance in the Core Strategy has taken account of both the objectives and the guidance in paragraphs 4.4 and 4.5 CC3 25-51 Neighbour- See Schedule 2 for details of changes to Neighbourhoods CC6 & 59- hoods and and Tolworth and Kingston Town Centre Key Areas of 69 Key Areas Changes. -

Riverside South (Kingston) Conservation Area

Riverside South (Kingston) Conservation Area The Riverside South Conservation Area (designated in February 2003) covers a linear area consisting of 240 properties situated along the east bank of the River Thames. It is within a Strategic Area of Special Character and is visible from Hampton Court Palace Gardens, Kingston Bridge and the barge path on the opposite bank. The residential strip along Portsmouth Road, the Queens Promenade (the river walk with associated riverside uses), and the former Seething Wells with Water Works are three recognizable character areas where the prevailing and historic uses have variously influenced the plan form and the building types of the area. Map and view of the Riverside conservation area. © Royal Borough of Kingston The interest of the Riverside South Conservation Area (CA) is associated with the ancient riverside estates and later Victorian benefactors. The domestic scale, rhythm and townscape quality of mainly pre-war or earlier buildings alongside or near the river frontage also adds to the architectural interest. Also of importance is the quality of the 19th century public works that established Queens Promenade as a place of recreation, together with the industrial/public health buildings and structures at Seething Wells Water Works. Brick is the dominant building material of the CA with red clay tile or slate roofing, stucco, white render and stone on the east side, complemented by the Arcadian planting along the west side of Portsmouth Road. More recently however, the landscape has suffered from poor maintenance and footways have become downgraded to tarmac on both sides of the road as is the surface of Queens Promenade. -

Surrey. I:Ingston-Upon-Thames

DIRECTORY.] SURREY. I:INGSTON-UPON-THAMES. 1357 Savage Henry, tailor, 23 Brook street Stone J. & Co. tailors, 4I Market place SaY&ge James, assistant turncock to the Lambeth water Strange George, cooper, Wood street works, Union street , Stratton, Gentry & Co. coal merchants, 4 Richmond road & Sawyer Charles, shopkeeper & beer retailer, Elm crescent Railway wharf, Cromwell road Scammell William, butcher. 70 Richmond road Stray & Sons, boot stores, 82 Richmond road Scott Joseph & William, carmen, Elm crescent Street Wm. & Co. mineral water manufactrs. Ashdown rd Scott James, grocer, 42 Thames street Street Charles, tobacconist, Fairfield road Scott William, carma-n, see Scott Joseph & William Stroud Charles, shopkeeper, Acre road Seabrook Daniel, butcher, 40 Thames street Stroud James, timber dealer, Acre road Searle Montague, linen draper, 39 Richmond road Strutt James, tailor, London street Searle William, beer retailer, Cowleaze road, Richmond rd Sully John, Crown & Thistle P.H. 2 Clarence street Sedgfield Russell, photog-rapher, Park road, Norbiton SUMMERS .JABEZ & SON, builders, contractors, builde"'rs• Segrove James, baker, Elm road & general ironmongers, Park road, Norbiton Sell & 'frounson, fancy repository, 7 Surbiton Park terrace, Summers Herbert J. bottle merchant, Fairfield west Surbiton road - Summers Mary Ann (Mrs.), dress maker, East road Sell Elizabeth (Mrs.),laundress, I Sedan villas, King's road Summers William, baker, Cambridge road, Norbiton Sergeant James W. slate, lime, cement & builders' mer- Sumner Charles, jun. cab proprietor, Portland road chant, 34 Clarence street Sumner James H. Three Jolly Sailors P.H. London street Seward Frederick, Albion P.H. Fa,irfield road Surbiton Cycle Depot (Ford & Co. proprietors), 6 & 7 Sewell Edwin, carpenter &c. -

Royal Borough of Kingston Upon Thames Locations Where Moving

ROYAL BOROUGH OF KINGSTON UPON THAMES LOCATIONS WHERE MOVING TRAFFIC CONTRAVENTIONS MAY OCCUR Location and Description TMO No. Restriction Surbiton and South of the Borough Neighbourhoods Davis Rd (junction Cox Lane) 1968-384 One Way Working Dunton Close - barrier (in unnamed road, between no. 9 & 'Monaro Cottage' Dunton Cl). 1990-05 No Vehicles The un-named road between Dunton Close & Southborough Road - barrier (in unnamed road, 1990-05 No Vehicles between no. 9 & 'Monaro Cottage' Dunton Cl). Gladstone Road, Surbiton - One-Way Working (eastern arm, w-e only). 1985-484 One Way Working Gladstone Road, Surbiton - One-Way Working (between Haycroft Rd & w-e arm, s-n only). 1985-484 One Way Working Haycroft Road, Surbiton - One-Way Working (between Gladstone Rd & Hook Rd, e-w only). 1985-484 One Way Working Herne Road - no right turn into Hook Road. 2004-62 Banned Turn Herne Road - no vehicles south-west of island site jcn Hook Road. 2004-62 No Vehicles Hook Road - no left turn into Herne Road. 2004-62 Banned Turn Width (to be Cox Lane – between Sanger Avenue and Oakcroft Road 1997-37 amended) Moor Lane - eastbound, no U turn (Gilders Rd). 2004-33 Banned Turn Moor Lane - Article 3 - no vehicles (service road, common boundary of No. 110 & Blackamoor's 1993-13 No Vehicles Head). Moor Lane - Article 3 - no vehicles (forecourt of Blackamoor's Head). 1993-13 No Vehicles (Weight limit 7.5 tonnes - Clayton) 1990-07 Weight Limit (Weight limit 7.5 tonnes - Chessington) 1987-05 Weight Limit Ashlyns Way - road blocked (junction Merritt Gdns) 2000-05 No Vehicles Bridge Road, Chessington - One-Way Working (opp nos 118-182, eastward only). -

Kingston University (2736).Pdf

Vice-Chancellor Hind Court Professor Steven Spier 106-114 London Road Hon FRIAS BDA FHEA FRSA Kingston upon Thames www.kingston.ac.uk KT2 6TN Sadiq Khan (Mayor of London) BY EMAIL [email protected] New London Plan GLA City Hall London Plan Team Post Point 18 FREEPOST RTJC-XBZZ-GJKZ London, SE1 2AA 27 February 2018 Draft London Plan Representations Kingston University has a vitally important educational and economic role within Greater London through the provision of high quality teaching for its students and as a major employer within the Royal Borough of Kingston upon Thames (RBK). There are approximately 15,000 students studying at the University’s four main campuses. The University also manages three residential sites within RBK (Clayhill, Seething Wells and Middle Mill). We welcome the opportunity to be involved in commenting on the draft London Plan. These representations provide feedback in relation to the policies proposed within the consultation document and are predominantly focused on Kingston, and on policies relating to educational use, recreation, design, conservation, affordable student accommodation and low cost workspaces and Metropolitan Open Land (MOL). We set out our comments on the draft London Plan below. Supporting London’s Growth/Opportunity Areas Kingston University supports the designation of the Kingston Opportunity Area and the recognition of Kingston as an area capable of accommodating development, including by intensification to provide leisure, cultural and night-time activity. The Royal Borough of Kingston upon Thames and Kingston Town Centre are key locations in which to focus the future growth of the capital. It is understood that Kingston First (Kingston’s Business Improvement District) supports this growth where it is appropriately balanced, and where there is appropriate mitigation against any adverse impacts. -

Seething Wells Halls of Residence, Portsmouth Road, Surbiton, Kt6 5Pj

Development Control Committee 11 July 2019 A3 & A4 Register No: 19/01207/FUL & 19/01212/LBC Address: SEETHING WELLS HALLS OF RESIDENCE, PORTSMOUTH ROAD, SURBITON, KT6 5PJ (c) Crown Copyright. All right reserved. Royal Borough of Kingston 2007. Licence number 100019285. [Please note that this plan is intended to assist in locating the development it is not the site plan of the proposed development which may have different boundaries. Please refer to the application documents for the proposed site boundaries.] Ward: St Marks Description of Proposal: Alterations and extensions of existing student Seething Wells Campus to provide additional student accommodation and ancillary facilities. Rooftop extensions to existing buildings to provide 159 new student rooms, alterations to Listed Buildings to provide a café, flexible meeting and recreation spaces and other ancillary facilities Plan Type: Full Application Expiry Date: Planning Policy and Guidance National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) National Planning Practice Guidance (web-based resource) Development Plan: Mayor for London London Plan March 2016 (consolidated with alterations since 2011) LDF Core Strategy Adopted April 2012 Kingston Town Centre AAP 2008 Policies LONDON PLAN (2016) LP 3.18 Education facilities LP 3.3 Increasing housing supply LP 3.4 Optimising housing potential LP 3.5 Quality and design of housing development LP 5.13 Sustainable drainage LP 5.2 Minimising carbon dioxide emissions LP 5.3 Sustainable design and construction LP 6.13 Parking LP 6.9 Cycling LP 7.4 Local -

Surrey History XII 2013

CONTENTS Seething Wells, Surbiton The Reeds of Oatlands: A Tudor Marriage Settlement The suppression of the Chantry College of St Peter, Lingfield Accessions of Records in Surrey History Centre, 2012 Index to volumes VIII to XII VOLUME XII 2013 SurreyHistory - 12 - Cover.indd 1 15/08/2013 09:34 SURREY LOCAL HISTORY COMMITTEE PUBLICATIONS SURREY ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY Chairman: Gerry Moss, 10 Hurstleigh Drive, Redhill, Surrey, RH1 2AA The former Surrey Local History Council produced Surrey History for many years and the majority of the back numbers are still available. In addition the following extra publications are in print: The Surrey Local History Committee, which is a committee of the Surrey Views of Surrey Churches Archaeological Society, exists to foster an interest in the history of Surrey. It does by C.T. Cracklow this by encouraging local history societies within the county, by the organisation (reprint of 1826 views) of meetings, by publication and also by co-operation with other bodies, to discover 1979 £7.50 (hardback) the past and to maintain the heritage of Surrey, in history, architecture, landscape and archaeology. Pastors, Parishes and People in Surrey The meetings organised by the Committee include a one-day Symposium on by David Robinson a local history theme and a half-day meeting on a more specialised subject. The 1989 £2.95 Committee produces Surrey History annually and other booklets from time to time. See below for publications enquires. Old Surrey Receipts and Food for Thought Membership of the Surrey Archaeological Society, our parent body, by compiled by Daphne Grimm local history societies, will help the Committee to express with authority the 1991 £3.95 importance of local history in the county.