Interventional Oncology: Guidance for Service Delivery Second Edition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Medical Oncology and Breast Cancer

The Breast Center Smilow Cancer Hospital 20 York Street, North Pavilion New Haven, CT 06510 Phone: (203) 200-2328 Fax: (203) 200-2075 MEDICAL ONCOLOGY Treatment for breast cancer is multidisciplinary. The primary physicians with whom you may meet as part of your care are the medical oncologist, the breast surgeon, and often the radiation oncologist. A list of these specialty physicians will be provided to you. Each provider works with a team of caregivers to ensure that every patient receives high quality, personalized, breast cancer care. The medical oncologist specializes in “systemic therapy”, or medications that treat the whole body. For women with early stage breast cancer, systemic therapy is often recommended to provide the best opportunity to prevent breast cancer from returning. SYSTEMIC THERAPY Depending on the specific characteristics of your cancer, your medical oncologist may prescribe systemic therapy. Systemic therapy can be hormone pills, IV chemotherapy, antibody therapy (also called “immunotherapy”), and oral chemotherapy; sometimes patients receive more than one type of systemic therapy. Systemic therapy can happen before surgery (called “neoadjuvant therapy”) or after surgery (“adjuvant therapy”). If appropriate, your breast surgeon and medical oncologist will discuss the benefits of neoadjuvant and adjuvant therapy with you. As a National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Member Institution, we are dedicated to following the treatment guidelines that have been shown to be most effective. We also have a variety of clinical trials that will help us find better ways to treat breast cancer. Your medical oncologist will recommend what treatment types and regimens are best for you. The information used to make these decisions include: the location of the cancer, the size of the cancer, the type of cancer, whether the cancer is invasive, the grade of the cancer (a measure of its aggressiveness), prognostic factors such as hormone receptors and HER2 status, and lymph node involvement. -

Infection Prevention in Outpatient Oncology Settings CDC Offers Tools to Fight Back Against Infections Among Cancer Patients

Infection prevention in outpatient oncology settings CDC offers tools to fight back against infections among cancer patients. By aLICE y. GUh, MD, MPh, LiSa c. RICHARDSOn, MD, MPh, AND ANGeLa DUnBAR, BS espite advances in oncology care, infections remain a major www.preventcancerinfections.org 1-3 cause of morbidity and mortality among cancer patients. 1. What? PREPARE: Watch Out for Fever! You should take your temperature any time you blood cell count is likely to be the lowest since in that you are a cancer patient undergoing When? feel warm, flushed, chilled or not well. If you get a this is when you’re most at risk for infection chemotherapy. If you have a fever, you might temperature of 100.4°F (38°C) or higher for more (also called nadir). have an infection. This is a life threatening Several factors predispose cancer patients to developing infec- than one hour, or a one-time temperature of 101° • Keep a working thermometer in a convenient condition, and you should be seen in a short F or higher, call your doctor immediately, even if location and know how to use it. amount of time. it is the middle of the night. DO NOT wait until the • Keep your doctor’s phone numbers with you at office re-opens before you call. all times. Make sure you know what number to call when their office is open and closed. tions, including immunosuppression from their underlying You should also: • If you have to go to the emergency room, it's • Find out from your doctor when your white important that you tell the person checking you • If you develop a fever during your chemotherapy treatment it is a medical emergency. -

Welcome to the Department of Oncology-Pathology

Photo: H. Flank WELCOME TO THE DEPARTMENT OF ONCOLOGY-PATHOLOGY Photo: S. Ceder Photo: Erik Cronberg Photo: H. Flank Photo: E. H. Cheteh & S. Ceder t. Solna JohanOlof Wallins väg Wallins JohanOlof SKALA Solregnsvägen 0255075 100 125 m Solna kyrkväg Solnavägen Prostvägen 1 Prostvägen DEPARTMENT OF Fogdevreten ONCOLOGY-PATHOLOGY Prostvägen Granits väg Science for Life Laboratory We are a part of Karolinska Institutet, where we work with cancer research and offer Solna kyrkväg educational programs at undergraduate, Master and doctoral levels. Uniting more Tomtebodavägen than 30 research groups, the department´s broad focus on cancer combines basic, translational and clinical research, ranging from mechanisms of cancer development and biomarkers to development of new technologies for precision cancer medicine. Spårområde Karolinska vägen Thus, our goals are, based on fundamental discoveries, to identify and implement Nobels väg Tomtebodavägen cancer biomarkers supporting early diagnosis and improved personalized therapy, Widerströmska building and to drive drug discovery via innovative clinical trials. Further, we engage in edu-Tomtebodavägen cation of next generation scientist and healthcare professionals in these areas.P Our research teams are mainly located at two research buildings, Bioclinicum and Science for Life Laboratories (SciLifeLab), Solna, and at hospital buildings including Pathology unit and New Karolinska Hospital (NKS), Stockholm. In addition, few Scheeles väg Theorells väg research groups form satellites in Södersjukhuset, Karolinska hospital in Huddinge 3 and at Cancercentrum Karolinska, Solna. Karolinska vägen Scheeles väg Retzius väg Nobels väg Biomedicum Solnavägen Science for Life laboratories Individual research groups are part of both the department of Oncology-Pathology and Tomtebodavägen the SciLifeLabs national infrastructure. -

Covid Management of Liquid Oncology Patients

CELLICONE VALLEY ‘21: THE FUTURE OF CELL AND GENE THERAPIES COVID MANAGEMENT OF LIQUID ONCOLOGY PATIENTS Abbey Walsh, MSN, RN, OCN – Clinical Practice Lead, Outpatient Infusion Therapy Angela Rubin, BSN, RN, OCN – Clinical Nurse III, Outpatient Infusion Therapy May 6th, 2021 Disclosures: ‣ Both presenters have disclosed no conflicts of interests related to this topic. 2 Objectives: ‣ Describe the evolution of COVID management for oncology patients being treated in ambulatory care. ‣ Identity the role of EUA monoclonal antibody treatments for COVID + oncology patients. ‣ Review COVID clearance strategies: past and present. ‣ Explain Penn Medicine's role in COVID vaccinations for oncology patients. ‣ Explain COVID – 19 special care considerations for oncology patients: • Emergency Management • Neutropenic Fevers/Infectious Work-ups • Nurse-Driven Initiatives • Cancer Center Initiatives to enhance patient safety and infection risk 3 Evolution of COVID Management for Oncology Patients in Ambulatory Care Late March – Early April 2020: COVID Testing Strategies “COLD” Testing “HOT” Testing • Assume these patients are COVID Negative. • Actively COVID + or suspicious for COVID/PUI • No need for escort in and out of the building (Patient under investigation) • Maintain Droplet Precautions: • Require RN/CNA escort in and out of building. • Enhanced PPE for COVID swab only • Enhanced precautions: • Patients who are asymptomatic but require • (Enhanced) Droplet + Contact COVID testing: • Upgrade to N95 during aerosolizing • Pre-admission procedures • Pre-procedural • (PUIs)-COVID testing indicated because of: New Symptoms, Recent Travel, Recent known exposure to Covid + individual • Examples: Port placement, starting radiation treatment, CarT therapy, Stem • Example: Liquid oncology patient arrives Cell/Bone Marrow Transplant patients for chemo treatment, but reports new cough and fevers up to 101 over the last • Exlcusion: pre-treatment outpatient anti- few days. -

Oncology 101 Dictionary

ONCOLOGY 101 DICTIONARY ACUTE: Symptoms or signs that begin and worsen quickly; not chronic. Example: James experienced acute vomiting after receiving his cancer treatments. ADENOCARCINOMA: Cancer that begins in glandular (secretory) cells. Glandular cells are found in tissue that lines certain internal organs and makes and releases substances in the body, such as mucus, digestive juices, or other fluids. Most cancers of the breast, pancreas, lung, prostate, and colon are adenocarcinomas. Example: The vast majority of rectal cancers are adenocarcinomas. ADENOMA: A tumor that is not cancer. It starts in gland-like cells of the epithelial tissue (thin layer of tissue that covers organs, glands, and other structures within the body). Example: Liver adenomas are rare but can be a cause of abdominal pain. ADJUVANT: Additional cancer treatment given after the primary treatment to lower the risk that the cancer will come back. Adjuvant therapy may include chemotherapy, radiation therapy, hormone therapy, targeted therapy, or biological therapy. Example: The decision to use adjuvant therapy often depends on cancer staging at diagnosis and risk factors of recurrence. BENIGN: Not cancerous. Benign tumors may grow larger but do not spread to other parts of the body. Also called nonmalignant. Example: Mary was relieved when her doctor said the mole on her skin was benign and did not require any further intervention. BIOMARKER TESTING: A group of tests that may be ordered to look for genetic alterations for which there are specific therapies available. The test results may identify certain cancer cells that can be treated with targeted therapies. May also be referred to as genetic testing, molecular testing, molecular profiling, or mutation testing. -

Interventional Radiology in the Diagnosis and Treatment of Solid Tumors

THE ROLE OF INTERVENTIONAL RADIOLOGY IN THE DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT OF SOLID TUMORS Victoria L. Anderson, MSN, CRNP, FAANP OBJECTIVES •Using Case Studies and Imaging examples: 1) Discuss the role interventional (IR) procedures to aid in diagnosing malignancy 2) Current and emerging techniques employed in IR to cure and palliate solid tumor malignancies will be explored Within 1 and 2 will be a discussion of research in the field of IR Q+A NIH Center for Interventional Oncology WHAT IS INTERVENTIONAL RADIOLOGY? • Considered once a subspecialty of Diagnostic Radiology • Now its own discipline, it serves to offer minimally invasive procedures using state-of- the-art modern medical advances that often replace open surgery (Society of Interventional Radiology) NIH Center for Interventional Oncology CHARLES T. DOTTER M.D. (1920-1985) • Father of Interventional Radiologist • Pioneer in the Field of Minimally Invasive Procedures (Catheterization) • Developed Continuous X-Ray Angio- Cardiography • Performed First If a plumber can do it to pipes, we can do it to blood vessels.” Angioplasty (PTCA) Charles T. Dotter M.D. Procedure in 1964. • Treated the first THE ROOTS OF patient with catheter assisted vascular INTERVENTIONAL dilation RADIOLOGY NIH Center for Interventional Oncology THE “DO NOT FIX” CONSULT THE DO NOT FIX PATIENT SCALES MOUNT HOOD WITH DR. DOTTER 1965 NIH Center for Interventional Oncology •FIRST EMBOLIZATION FOR GI BLEEDING •ALLIANCE WITH •FIRST BALLOON BILL COOK •HIGH SPEED PERIPHERAL DEVELOPED RADIOGRAPHY ANGIOPLASTY-- NUMEROUS -

Unique Issues Facing Primary Care Providers

What is Primary Care Oncology? Unique Issues Facing Primary Care Providers Amy E. Shaw, MD Medical Director, Cancer Survivorship and Primary Care Oncology Annadel Medical Group Santa Rosa, California January 16, 2016 The Breast Cancer Journey: Together with Primary Care Bellingham, Washington This CME presentation was developed independent of any commercial influences Trends in Incidence Rates for Selected Cancers, United States, 1975 - 2011. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians Volume 65, Issue 1, JAN 2015 Trends in Death Rates Overall and for Selected Sites, United States, 1930 - 2011 CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians Volume 65, Issue 1, pages 5-29, 5 JAN 2015 Trend in 5-Year Survival 1971-2005 Source: The State of Cancer Care in America: 2014; ASCO * Due to earlier detection and more effective treatments. 2005: Cancer Survivor care lacking • 10 million cancer survivors • Institute of Medicine report: • From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition • Identified a discontinuity (“gap”) in care between acute cancer care and primary care • Proposed solutions, set goals 1. Surveillance and screening • Cancer recurrence, new primary cancers, complications of cancer treatment 2. Prevention of late effects of cancer treatment or second cancers 3. Promotion of Healthy Lifestyle • Risk reduction counseling and interventions 4. Coordination of care and communication • Continuity of care between specialists and primary care physicians 5. Treatment • Of ongoing or late-onset physical and psychological symptoms of cancer or cancer therapies (NOT TREATMENT OF CANCER) Institute of Medicine. From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition. 2005 2015: 10 years later How are we doing? 2015: CDC Report • Now 15 million cancer survivors • 24 million cancer survivors by 2025 • Survivorship Programs in many hospitals • Medical care of survivors still lacking • Example: 60% of breast cancer patients report cognitive impairment after cancer treatment. -

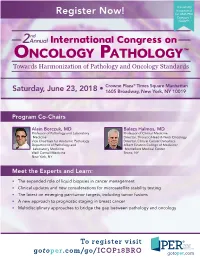

ONCOLOGY PATHOLOGY™ Towards Harmonization of Pathology and Oncology Standards

This activity is approved Register Now! for AMA PRA Category 1 Credit™. nd 2 Annual International Congress on ONCOLOGY PATHOLOGY™ Towards Harmonization of Pathology and Oncology Standards Crowne Plaza® Times Square Manhattan Saturday, June 23, 2018 • 1605 Broadway, New York, NY 10019 Program Co-Chairs Alain Borczuk, MD Balazs Halmos, MD Professor of Pathology and Laboratory Professor of Clinical Medicine Medicine Director, Thoracic/Head & Neck Oncology Vice Chairman for Anatomic Pathology Director, Clinical Cancer Genomics Department of Pathology and Albert Einstein College of Medicine/ Laboratory Medicine Montefiore Medical Center Weill Cornell Medicine Bronx, NY New York, NY Meet the Experts and Learn: • The expanded role of liquid biopsies in cancer management • Clinical updates and new considerations for microsatellite stability testing • The latest on emerging pan-tumor targets, including tumor fusions • A new approach to prognostic staging in breast cancer • Multidisciplinary approaches to bridge the gap between pathology and oncology To register visit gotoper.com/go/ICOP18BRO Meeting Overview The 2nd Annual International Congress on Oncology Pathology™: Towards Harmonization of Pathology and Oncology Standards will provide the latest information on key topics in pathology that can readily be applied to clinical practice in a variety of settings. This congress will bring together oncologists and pathologists to facilitate awareness of recent advancements in the field of cancer pathology and enhance multidisciplinary collaboration. -

Advances in Radiation Oncology

Advances in Radiation Oncology COVID-19 infection prevention and control practices in Wuhan radiotherapy --Manuscript Draft-- Manuscript Number: ADVANCESRADONC-D-20-00120R1 Article Type: Letter to the Editor Section/Category: Clinical Investigation - Other Corresponding Author: Steven J Chmura, MD, PhD University of Chicago Chicago, IL United States First Author: Cheng Chen, M.Sc. Order of Authors: Cheng Chen, M.Sc. Zhengkai Liao, M.D., Ph.D. Steven J Chmura, MD, PhD Ralph R. Weichselbaum, M.D. Abstract: Radiotherapy outcomes depend on the presence of skilled technical staff. There is concern as to how to protect staff and patients when receiving daily radiotherapy. In Wuhan, during the COVID-19 outbreak from January 28 2020 to March 10 2020, 153 patients with 1,752 visits underwent radiotherapy in Zhongnan Hospital. Of 39 staff personnel none as yet have developed symptoms and / or molecular indication of COVID-19 infection, including SARS-Cov-2 Real-time RT-PCR, IgM, and IgG. To achieve these results, we implemented the measures outlined below (Figure 1). Powered by Editorial Manager® and ProduXion Manager® from Aries Systems Corporation Title Page (WITH Author Details) COVID-19 infection prevention and control practices in Wuhan radiotherapy Cheng Chen, M.Sc.1, Zhengkai Liao, M.D., Ph.D.1*, Steven J. Chmura, M.D., Ph.D.2, Ralph R. Weichselbaum, M.D.2 1 Department of Radiation and Medical Oncology, and Hubei Cancer Clinical Study Center, Zhongnan Hospital of Wuhan University, Wuhan, Hubei 430070, China 2 Department of Radiation and Cellular Oncology, and the Ludwig Center for Metastasis Research, University of Chicago Medicine, Chicago IL 60637 * Correspondence: Zhengkai Liao, M.D., Ph.D. -

Analysis of Body Mass Index and Mortality in Patients with Colorectal Cancer Using Causal Diagrams

Research JAMA Oncology | Original Investigation Analysis of Body Mass Index and Mortality in Patients With Colorectal Cancer Using Causal Diagrams Candyce H. Kroenke, ScD; Romain Neugebauer, PhD; Jeffrey Meyerhardt, MD; Carla M. Prado, PhD; Erin Weltzien, BA; Marilyn L. Kwan, PhD; Jingjie Xiao, MS; Bette J. Caan, DrPH Editorial page 1127 IMPORTANCE Physicians and investigators have sought to determine the relationship Supplemental content between body mass index (BMI [calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared]) and colorectal cancer (CRC) outcomes, but methodologic limitations including sampling selection bias, reverse causality, and collider bias have prevented the ability to draw definitive conclusions. OBJECTIVE To evaluate the association of BMI at the time of, and following, colorectal cancer (CRC) diagnosis with mortality in a complete population using causal diagrams. DESIGN, SETTING, AND PARTICIPANTS This retrospective observational study with prospectively collected data included a cohort of 3408 men and women, ages 18 to 80 years, from the Kaiser Permanente Northern California population, who were diagnosed with stage I to III CRC between 2006 and 2011 and who also had surgery. EXPOSURES Body mass index at diagnosis and 15 months following diagnosis. MAIN OUTCOMES AND MEASURES Hazard ratios (HRs) for all-cause mortality and CRC-specific mortality compared with normal-weight patients, adjusted for sociodemographics, disease severity, treatment, and prediagnosis BMI. RESULTS This study investigated a cohort of 3408 men and women ages 18 to 80 years diagnosed with stage I to III CRC between 2006 and 2011 who also had surgery. At-diagnosis BMI was associated with all-cause mortality in a nonlinear fashion, with patients who were underweight (BMI <18.5; HR, 2.65; 95% CI, 1.63-4.31) and patients who were class II or III obese (BMI Ն35; HR, 1.33; 95% CI, 0.89-1.98) exhibiting elevated mortality risks, compared with patients who were low-normal weight (BMI 18.5 to <23). -

Is Interventional Oncology Ready to Stand on Its Own? Interventional Oncology Sets Aim on Becoming the Fourth Pillar in the Treatment of Cancer

INTERVENTIONAL ONCOLOGY Point/Counterpoint: Is Interventional Oncology Ready to Stand on Its Own? Interventional oncology sets aim on becoming the fourth pillar in the treatment of cancer. Yes, it is! LEADING GROWTH IN IR FOR 20 YEARS The economic engine of IR for the past 2 decades has BY MICHAEL C. SOULEN, MD, FSIR, FCIRSE been IO, outstripping growth in other vascular and non- vascular IR disciplines. Furthermore, IO procedures have have been practicing interventional oncology (IO) for higher revenue per relative value unit than vascular inter- almost 25 years (most interventional radiologists prob- ventions, so a full-time equivalent in IO is more valuable ably have to a greater or lesser extent). The treatment of than one focusing on arterial diseases. IO is also a driver cancer by interventional radiologists dates back to the of growth for industry—interventional oncologists I1950s, even before interventional radiology (IR) was rec- consume 10 times more product than interventional ognized as a discipline.1 Our “founding fathers” published radiologists from the same group who do not have an extensively on minimally invasive, image-guided cancer oncologic practice (Figure 1). IO is spurring the surge of therapy through the 1960s and ‘70s.2-4 Tumor emboliza- interest in IR among medical students and residents. tion has been a standard of care for 3 decades, and tumor ablation has been common practice for the past 15 years. A Fortuitous Convergence Palliative procedures for management of cancer-related The evolution of IO from “something we do” into a obstruction, pain management, and provision of enteral full clinical discipline was born from the convergence of and venous access are routine IR practice. -

Ablation in Pancreatic Cancer: Past, Present and Future

cancers Review Ablation in Pancreatic Cancer: Past, Present and Future Govindarajan Narayanan 1,2,3,*, Dania Daye 4, Nicole M. Wilson 3, Raihan Noman 3, Ashwin M. Mahendra 5 and Mehul H. Doshi 6,7 1 Miami Cancer Institute, Baptist Health South Florida, Miami, FL 33176, USA 2 Miami Cardiac and Vascular, Baptist Health South Florida, Miami, FL 33176, USA 3 Herbert Wertheim College of Medicine, Florida International University, Miami, FL 33199, USA; nwils027@med.fiu.edu (N.M.W.); rnoma001@med.fiu.edu (R.N.) 4 Division of Vascular and Interventional Radiology, Department of Radiology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Harvard University, Boston, MA 02114, USA; [email protected] 5 Pratt School of Engineering, Duke University, Durham, NC 27708, USA; [email protected] 6 Department of Radiology, Cleveland Clinic Florida, Weston, FL 33331, USA; [email protected] 7 Charles E. Schmidt College of Medicine, Florida Atlantic University, Boca Raton, FL 33431, USA * Correspondence: [email protected] Simple Summary: Despite advancements in surgical oncology and chemoradiation therapies, pancre- atic cancer still has one of the lowest 5-year survival rates in the United States. The silent progression of this disease often leads to it being identified after it has already reached an advanced and often unresectable stage. The field of interventional oncology has yielded ablation strategies with the potential to downstage and increase survival rates in patients suffering from locally advanced pan- creatic cancer. This review examines the treatment strategies for locally advanced pancreatic cancer, discussing current results and future directions. Citation: Narayanan, G.; Daye, D.; Abstract: The insidious onset and aggressive nature of pancreatic cancer contributes to the poor Wilson, N.M.; Noman, R.; Mahendra, treatment response and high mortality of this devastating disease.