Whatever Happened to Carolyn M. Rodgers?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ishmael Reed Interviewed

Boxing on Paper: Ishmael Reed Interviewed by Don Starnes [email protected] http://www.donstarnes.com/dp/ Don Starnes is an award winning Director and Director of Photography with thirty years of experience shooting in amazing places with fascinating people. He has photographed a dozen features, innumerable documentaries, commercials, web series, TV shows, music and corporate videos. His work has been featured on National Geographic, Discovery Channel, Comedy Central, HBO, MTV, VH1, Speed Channel, Nerdist, and many theatrical and festival screens. Ishmael Reed [in the white shirt] in New Orleans, Louisiana, September 2016 (photo by Tennessee Reed). 284 Africology: The Journal of Pan African Studies, vol.10. no.1, March 2017 Editor’s note: Here author (novelist, essayist, poet, songwriter, editor), social activist, publisher and professor emeritus Ishmael Reed were interviewed by filmmaker Don Starnes during the 2014 University of California at Merced Black Arts Movement conference as part of an ongoing film project documenting powerful leaders of the Black Arts and Black Power Movements. Since 2014, Reed’s interview was expanded to take into account the presidency of Donald Trump. The title of this interview was supplied by this publication. Ishmael Reed (b. 1938) is the winner of the prestigious MacArthur Fellowship (genius award), the renowned L.A. Times Robert Kirsch Lifetime Achievement Award, the Lila Wallace-Reader's Digest Award, a Guggenheim Fellowship, and a Rosenthal Family Foundation Award from the National Institute for Arts and Letters. He has been nominated for a Pulitzer and finalist for two National Book Awards and is Professor Emeritus at the University of California at Berkeley (a thirty-five year presence); he has also taught at Harvard, Yale and Dartmouth. -

Sangamon State University a Springfield, IL 62708

s~'$$$ Sangamon State University a Springfield, IL 62708 Volume 3, Number 1 Office of University Relations August 28,1986 PAC 569 786-6716 CONVOCOM To Air Soccer Game Welcome The SSU TV Office will tape coverage of The SSU WEEKLY staff extends greetings to the Prairie StarsIQuincy College soccer game all new and returning students, faculty and on Friday, September 5, at Quincy for later staff at the beginning of this fall semester. broadcast on CONVOCOM. The game will air on The WEEKLY contains stories about faculty, three CONVOCOM channels, WJPT in Jackson- staff and studqnts and various University ville, WQEC in Quincy and WIUM-TV in Macomb, events and activities. beginning at 8:30 p.m. on Friday, September Please send news items to your program 5, and 8 p.m. on Saturday, September 6 (The coordinator or unit administrator to be game actually begins at 7 p.m. on Sep- submitted to SSU WEEKLY, PAC 569, by the tember 5). Springfield area residents will Monday prior to the publication date. The be able to see the game on WJPT, cable WEEKLY is printed every Thursday. If you channel 23. have any questions regarding the SSU WEEKLY, The game is part of a four-team call 786-6716. tournament. Southern Illinois University at Edwardsville will play the Air Force Academy Reminders at 5 p.m. on September 5. *The University will be closed Monday, Amnesty Program September 1, for the observance of Labor Day. The University will be open Tuesday, In an effort to reduce the number and September 2, but no classes are scheduled. -

The Black Arts Enterprise and the Production of African American Poetry

0/-*/&4637&: *ODPMMBCPSBUJPOXJUI6OHMVFJU XFIBWFTFUVQBTVSWFZ POMZUFORVFTUJPOT UP MFBSONPSFBCPVUIPXPQFOBDDFTTFCPPLTBSFEJTDPWFSFEBOEVTFE 8FSFBMMZWBMVFZPVSQBSUJDJQBUJPOQMFBTFUBLFQBSU $-*$,)&3& "OFMFDUSPOJDWFSTJPOPGUIJTCPPLJTGSFFMZBWBJMBCMF UIBOLTUP UIFTVQQPSUPGMJCSBSJFTXPSLJOHXJUI,OPXMFEHF6OMBUDIFE ,6JTBDPMMBCPSBUJWFJOJUJBUJWFEFTJHOFEUPNBLFIJHIRVBMJUZ CPPLT0QFO"DDFTTGPSUIFQVCMJDHPPE The Black Arts Enterprise and the Production of African American Poetry The Black Arts Enterprise and the Production of African American Poetry Howard Rambsy II The University of Michigan Press • Ann Arbor First paperback edition 2013 Copyright © by the University of Michigan 2011 All rights reserved Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America c Printed on acid-free paper 2016 2015 2014 2013 5432 No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher. A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Rambsy, Howard. The black arts enterprise and the production of African American poetry / Howard Rambsy, II. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-472-11733-8 (cloth : acid-free paper) 1. American poetry—African American authors—History and criticism. 2. Poetry—Publishing—United States—History—20th century. 3. African Americans—Intellectual life—20th century. 4. African Americans in literature. I. Title. PS310.N4R35 2011 811'.509896073—dc22 2010043190 ISBN 978-0-472-03568-7 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-472-12005-5 (e-book) Cover illustrations: photos of writers (1) Haki Madhubuti and (2) Askia M. Touré, Mari Evans, and Kalamu ya Salaam by Eugene B. Redmond; other images from Shutterstock.com: jazz player by Ian Tragen; African mask by Michael Wesemann; fist by Brad Collett. -

Alternative Perspectives of African American Culture and Representation in the Works of Ishmael Reed

ALTERNATIVE PERSPECTIVES OF AFRICAN AMERICAN CULTURE AND REPRESENTATION IN THE WORKS OF ISHMAEL REED A thesis submitted to the faculty of San Francisco State University In partial fulfillment of Zo\% The requirements for IMl The Degree Master of Arts In English: Literature by Jason Andrew Jackl San Francisco, California May 2018 Copyright by Jason Andrew Jackl 2018 CERTIFICATION OF APPROVAL I certify that I have read Alternative Perspectives o f African American Culture and Representation in the Works o f Ishmael Reed by Jason Andrew Jackl, and that in my opinion this work meets the criteria for approving a thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree Master of Arts in English Literature at San Francisco State University. Geoffrey Grec/C Ph.D. Professor of English Sarita Cannon, Ph.D. Associate Professor of English ALTERNATIVE PERSPECTIVES OF AFRICAN AMERICAN CULTURE AND REPRESENTATION IN THE WORKS OF ISHMAEL REED Jason Andrew JackI San Francisco, California 2018 This thesis demonstrates the ways in which Ishmael Reed proposes incisive countemarratives to the hegemonic master narratives that perpetuate degrading misportrayals of Afro American culture in the historical record and mainstream news and entertainment media of the United States. Many critics and readers have responded reductively to Reed’s work by hastily dismissing his proposals, thereby disallowing thoughtful critical engagement with Reed’s views as put forth in his fiction and non fiction writing. The study that follows asserts that Reed’s corpus deserves more thoughtful critical and public recognition than it has received thus far. To that end, I argue that a critical re-exploration of his fiction and non-fiction writing would yield profound contributions to the ongoing national dialogue on race relations in America. -

Publishing Blackness: Textual Constructions of Race Since 1850

0/-*/&4637&: *ODPMMBCPSBUJPOXJUI6OHMVFJU XFIBWFTFUVQBTVSWFZ POMZUFORVFTUJPOT UP MFBSONPSFBCPVUIPXPQFOBDDFTTFCPPLTBSFEJTDPWFSFEBOEVTFE 8FSFBMMZWBMVFZPVSQBSUJDJQBUJPOQMFBTFUBLFQBSU $-*$,)&3& "OFMFDUSPOJDWFSTJPOPGUIJTCPPLJTGSFFMZBWBJMBCMF UIBOLTUP UIFTVQQPSUPGMJCSBSJFTXPSLJOHXJUI,OPXMFEHF6OMBUDIFE ,6JTBDPMMBCPSBUJWFJOJUJBUJWFEFTJHOFEUPNBLFIJHIRVBMJUZ CPPLT0QFO"DDFTTGPSUIFQVCMJDHPPE publishing blackness publishing blackness Textual Constructions of Race Since 1850 George Hutchinson and John K. Young, editors The University of Michigan Press Ann Arbor Copyright © by the University of Michigan 2013 All rights reserved This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher. Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America c Printed on acid- free paper 2016 2015 2014 2013 4 3 2 1 A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Publishing blackness : textual constructions of race since 1850 / George Hutchinson and John Young, editiors. pages cm — (Editorial theory and literary criticism) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978- 0- 472- 11863- 2 (hardback) — ISBN (invalid) 978- 0- 472- 02892- 4 (e- book) 1. American literature— African American authors— History and criticism— Theory, etc. 2. Criticism, Textual. 3. American literature— African American authors— Publishing— History. 4. Literature publishing— Political aspects— United States— History. 5. African Americans— Intellectual life. 6. African Americans in literature. I. Hutchinson, George, 1953– editor of compilation. II. Young, John K. (John Kevin), 1968– editor of compilation PS153.N5P83 2012 810.9'896073— dc23 2012042607 acknowledgments Publishing Blackness has passed through several potential versions before settling in its current form. -

Blues Tribute Poems in Twentieth- and Twenty-First Century American Poetry Emily Rutter

Duquesne University Duquesne Scholarship Collection Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2014 Constructions of the Muse: Blues Tribute Poems in Twentieth- and Twenty-First Century American Poetry Emily Rutter Follow this and additional works at: https://dsc.duq.edu/etd Recommended Citation Rutter, E. (2014). Constructions of the Muse: Blues Tribute Poems in Twentieth- and Twenty-First Century American Poetry (Doctoral dissertation, Duquesne University). Retrieved from https://dsc.duq.edu/etd/1136 This Immediate Access is brought to you for free and open access by Duquesne Scholarship Collection. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Duquesne Scholarship Collection. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CONSTRUCTIONS OF THE MUSE: BLUES TRIBUTE POEMS IN TWENTIETH- AND TWENTY-FIRST-CENTURY AMERICAN POETRY A Dissertation Submitted to the McAnulty College of Liberal Arts Duquesne University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Emily Ruth Rutter March 2014 Copyright by Emily Ruth Rutter 2014 ii CONSTRUCTIONS OF THE MUSE: BLUES TRIBUTE POEMS IN TWENTIETH- AND TWENTY-FIRST-CENTURY AMERICAN POETRY By Emily Ruth Rutter Approved March 12, 2014 ________________________________ ________________________________ Linda A. Kinnahan Kathy L. Glass Professor of English Associate Professor of English (Committee Chair) (Committee Member) ________________________________ ________________________________ Laura Engel Thomas P. Kinnahan Associate Professor of English Assistant Professor of English (Committee Member) (Committee Member) ________________________________ ________________________________ James Swindal Greg Barnhisel Dean, McAnulty College of Liberal Arts Chair, English Department Professor of Philosophy Associate Professor of English iii ABSTRACT CONSTRUCTIONS OF THE MUSE: BLUES TRIBUTE POEMS IN TWENTIETH- AND TWENTY-FIRST-CENTURY AMERICAN POETRY By Emily Ruth Rutter March 2014 Dissertation supervised by Professor Linda A. -

The Progressive Stages of the Black Aesthetic in Literature

Notes 1. TOTAL LIFE IS WHAT WE WANT: THE PROGRESSIVE STAGES OF THE BLACK AESTHETIC IN LITERATURE 1. This was the problem of nomenclature that had bogged down some of Douglass' thoughts toward the correction of racism. He was tom, as was true of many black leaders, between a violent response to white violence and arrogance, and his own Christian principles. Yet this dissonance did not lead to inaction: cf., the commentary preceding The Life and Times of Frederick Douglass' in Early American Negro Writers, edited by Benjamin Brawley (New York: Dover, 1970). 2. Although I have chosen as the focus of my inquiry Major, Baker, Gayle, and Baraka because of the quantity and quality of their comments, and because of their association with Reed, it is still an arbitrary choice which excludes many other critics who were import ant to the formation of the new black aesthetic. Certainly Hoyt Fuller, the former editor of Black World, deserves his place among the leading black aestheticians, as does Larry Neal. An excellent reference for a more full discussion of other personalities in the new black aesthetic is Propaganda and Aesthetics: The Literary Politics of Afro-American Maga zines in the Twentieth Century, by Abby A. Johnson and Ronald Mayberry Johnson (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1979). 3. This method of delivery was one of the mainstays of effective communication for those obsessed with the power of the word in the 1960s: Baraka, Cleaver, Sonia Sanchez, even Jane Fonda. Ntozake Shange would write in 1980 that blacks had so claimed 'the word' that it hardly mattered who spoke or what was said; the listener was immediately comfortable with simply the grace and rhythm of the words issuing forth. -

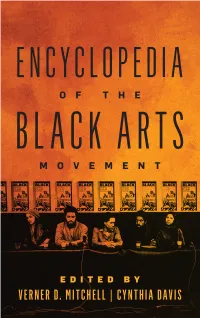

Here May Is Not Rap Be Music D in Almost Every Major Language,Excerpted Including Pages Mandarin

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF THE BLACK ARTS MOVEMENT ed or printed. Edited by istribut Verner D. Mitchell Cynthia Davis an uncorrected page proof and may not be d Excerpted pages for advance review purposes only. All rights reserved. This is ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD Lanham • Boulder • New York • London 18_985_Mitchell.indb 3 2/25/19 2:34 PM ed or printed. Published by Rowman & Littlefield An imprint of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc. 4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706 istribut www.rowman.com 6 Tinworth Street, London, SE11 5AL, United Kingdom Copyright © 2019 by The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Mitchell, Verner D., 1957– author. | Davis, Cynthia, 1946– author. Title: Encyclopedia of the Black Arts Movement / Verner D. Mitchell, Cynthia Davis. Description: Lanhaman : uncorrectedRowman & Littlefield, page proof [2019] and | Includes may not bibliographical be d references and index. Identifiers:Excerpted LCCN 2018053986pages for advance(print) | LCCN review 2018058007 purposes (ebook) only. | AllISBN rights reserved. 9781538101469This is (electronic) | ISBN 9781538101452 | ISBN 9781538101452 (cloth : alk. paper) Subjects: LCSH: Black Arts movement—Encyclopedias. Classification: LCC NX512.3.A35 (ebook) | LCC NX512.3.A35 M58 2019 (print) | DDC 700.89/96073—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018053986 The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992. -

American Book Awards 2004

BEFORE COLUMBUS FOUNDATION PRESENTS THE AMERICAN BOOK AWARDS 2004 America was intended to be a place where freedom from discrimination was the means by which equality was achieved. Today, American culture THE is the most diverse ever on the face of this earth. Recognizing literary excel- lence demands a panoramic perspective. A narrow view strictly to the mainstream ignores all the tributaries that feed it. American literature is AMERICAN not one tradition but all traditions. From those who have been here for thousands of years to the most recent immigrants, we are all contributing to American culture. We are all being translated into a new language. BOOK Everyone should know by now that Columbus did not “discover” America. Rather, we are all still discovering America—and we must continue to do AWARDS so. The Before Columbus Foundation was founded in 1976 as a nonprofit educational and service organization dedicated to the promotion and dissemination of contemporary American multicultural literature. The goals of BCF are to provide recognition and a wider audience for the wealth of cultural and ethnic diversity that constitutes American writing. BCF has always employed the term “multicultural” not as a description of an aspect of American literature, but as a definition of all American litera- ture. BCF believes that the ingredients of America’s so-called “melting pot” are not only distinct, but integral to the unique constitution of American Culture—the whole comprises the parts. In 1978, the Board of Directors of BCF (authors, editors, and publishers representing the multicultural diversity of American Literature) decided that one of its programs should be a book award that would, for the first time, respect and honor excellence in American literature without restric- tion or bias with regard to race, sex, creed, cultural origin, size of press or ad budget, or even genre. -

Biographical Description for the Historymakers® Video Oral History with Angela Jackson

Biographical Description for The HistoryMakers® Video Oral History with Angela Jackson PERSON Jackson, Angela, 1951- Alternative Names: Angela Jackson; Life Dates: July 25, 1951- Place of Birth: Greenville, Mississippi, USA Residence: Chicago, IL Occupations: Playwright; Poet Biographical Note Angela Jackson, poet, playwright and fictionist, was born July 25, 1951, in Greenville, Mississippi. Her father, George Jackson, Sr. and mother, Angeline Robinson Jackson moved to Chicago where Jackson attended St. Anne’s Catholic School. Fascinated with books, Jackson frequented the Kelly Branch Library and admired Chicago’s Gwendolyn Brooks. She graduated from Loretto Academy in 1968 with a pre- med scholarship to Northwestern University. In 1977, Jackson received her B.A. degree from Northwestern University and went on to earn her M.A. degree from Jackson received her B.A. degree from Northwestern University and went on to earn her M.A. degree from the University of Chicago. At Northwestern University, Jackson joined FMO, the black student union. Influenced by artist Jeff Donaldson and visiting poet Margaret Walker, she was invited by Johnson Publishing’s Black World magazine editor, Hoyt W. Fuller, to join the Organization for Black American Culture (OBAC), where she stayed as a member for twenty years. At OBAC, Fuller mentored young black writers like Haki Madhubuti (Don L. Lee), Carolyn Rodgers, Sterling Plumpp and others. Jackson was praised as a reader and performer on Chicago’s burgeoning black literary scene. First published nationally in Black World in 1971, Jackson’s first book of poetry, Voodoo Love Magic was published by Third World Press in 1974. She won the eighth Conrad Kent Rivers Memorial Award in 1973; the Academy of American Poets Award from Northwestern University in 1974; the Illinois Art Council Creative Writing Fellowship in Fiction in 1979; a National Endowment For the Arts Creative Writing Fellowship in Fiction in 1980; the Hoyt W. -

Angela Jackson

This program is partially supported by a grant from the Illinois Arts Council, a state agency. ANGELA JACKSON A renowned Chicago poet, novelist, play- wright, and biographer, Angela Jackson published her first book while still a stu- dent at Northwestern University. Though Jackson has achieved acclaim in multi- ple genres, and plans in the near future to add short stories and memoir to her oeuvre, she first and foremost considers herself a poet. The Poetry Foundation website notes that “Jackson’s free verse poems weave myth and life experience, conversation, and invocation.” She is also renown for her passionate and skilled Photo by Toya Werner-Martin public poetry readings. Born on July 25, 1951, in Greenville, Mississippi, Jackson moved with her fam- ily to Chicago’s South Side at the age of one. Jackson’s father, George Jackson, Sr., and mother, Angeline Robinson, raised nine children, of which Angela was the middle child. Jackson did her primary education at St. Anne’s Catholic School and her high school work at Loretto Academy, where she earned a pre-medicine scholar- ship to Northwestern University. Jackson switched majors and graduated with a B.A. in English and American Literature from Northwestern University in 1977. She later earned her M.A. in Latin American and Caribbean studies from the University of Chicago, and, more recently, received an M.F.A. in Creative Writing from Bennington College. While at Northwestern, Jackson joined the Organization for Black American Culture (OBAC), where she matured under the guidance of legendary literary figures such as Hoyt W Fuller. -

Montana Kaimin, October 11, 1979 Associated Students of the University of Montana

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Associated Students of the University of Montana Montana Kaimin, 1898-present (ASUM) 10-11-1979 Montana Kaimin, October 11, 1979 Associated Students of the University of Montana Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/studentnewspaper Recommended Citation Associated Students of the University of Montana, "Montana Kaimin, October 11, 1979" (1979). Montana Kaimin, 1898-present. 6865. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/studentnewspaper/6865 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Associated Students of the University of Montana (ASUM) at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Montana Kaimin, 1898-present by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Common Cause chief blasts energy politics the bill for environmentally un By CATHY KRADOLFER that fluctuated between 25 and 75 and marketing of power in the power plant projects. As part of the Montana Kalmln Reporter persons attended the forum spon Pacific Northwest. Its ad agreement, the BPA would sound policies" such as strip sored by th.e Student Action ministrator is appointed by the guarantee that it would provide a mining and synthetic fuel produc Government agencies and of Center as part of the week-long president. market for the electricity produced tion. He charged that the Carter ad ficials are trying to "subvert" "Conference on the Environment." Senate Bill 885, which has pass by the plant. ministration's energy policy is citizen participation in energy ed the Senate and will soon be The legislation, Richards said, policy decisions, the state director Blasts BPA bill considered by the House of would give the BPA an "open door” backed by business interests such of Common Cause said in Richards said legislation before Representatives, will allow the to build more coal-fired generating as oil companies.