Spillovers and Substitutability in Production

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A's News Clips, Thursday, March 3, 2011 A's Outfielder Coco Crisp

A’s News Clips, Thursday, March 3, 2011 A's outfielder Coco Crisp arrested on suspicion of DUI By Joe Stiglich Oakland Tribune A's center fielder Coco Crisp was arrested on suspicion of driving under the influence of alcohol early Wednesday morning, according to an A's news release. Crisp was detained and taken to City of Scottsdale Jail before being released Wednesday morning. He showed up to Phoenix Municipal Stadium on time to join the team for pre-game drills and was in uniform -- but not in the lineup -- for a game against the Cleveland Indians. Crisp declined to comment when asked about the situation, saying he would address the media "in due time." "The A's are aware of the situation and take such matters seriously," the A's statement read. "The team and Coco will have no further comment until further details are available." Crisp, 31, is in his second season with the A's and is slated to play center field and be the leadoff hitter. Ironically, the A's held a security meeting with Major League Baseball officials before taking the field Wednesday. A message that is stressed in the annual meeting is having awareness of the off-field dangers that exist for professional athletes. Crisp signed with the A's as a free agent in December 2009. He hit .279 with eight homers and 38 RBIs last season but played in just 75 games because of a fractured pinkie and strained rib cage muscle. Crisp posts frequently on his Twitter account and often makes reference to his nighttime socializing. -

Boston Baseball Dynasties: 1872-1918 Peter De Rosa Bridgewater State College

Bridgewater Review Volume 23 | Issue 1 Article 7 Jun-2004 Boston Baseball Dynasties: 1872-1918 Peter de Rosa Bridgewater State College Recommended Citation de Rosa, Peter (2004). Boston Baseball Dynasties: 1872-1918. Bridgewater Review, 23(1), 11-14. Available at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/br_rev/vol23/iss1/7 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. Boston Baseball Dynasties 1872–1918 by Peter de Rosa It is one of New England’s most sacred traditions: the ers. Wright moved the Red Stockings to Boston and obligatory autumn collapse of the Boston Red Sox and built the South End Grounds, located at what is now the subsequent calming of Calvinist impulses trembling the Ruggles T stop. This established the present day at the brief prospect of baseball joy. The Red Sox lose, Braves as baseball’s oldest continuing franchise. Besides and all is right in the universe. It was not always like Wright, the team included brother George at shortstop, this. Boston dominated the baseball world in its early pitcher Al Spalding, later of sporting goods fame, and days, winning championships in five leagues and build- Jim O’Rourke at third. ing three different dynasties. Besides having talent, the Red Stockings employed innovative fielding and batting tactics to dominate the new league, winning four pennants with a 205-50 DYNASTY I: THE 1870s record in 1872-1875. Boston wrecked the league’s com- Early baseball evolved from rounders and similar English petitive balance, and Wright did not help matters by games brought to the New World by English colonists. -

San Francisco Giants

SAN FRANCISCO GIANTS 2016 END OF SEASON NOTES 24 Willie Mays Plaza • San Francisco, CA 94107 • Phone: 415-972-2000 sfgiants.com • sfgigantes.com • sfgiantspressbox.com • @SFGiants • @SFGigantes • @SFG_Stats THE GIANTS: Finished the 2016 campaign (59th in San Francisco and 134th GIANTS BY THE NUMBERS overall) with a record of 87-75 (.537), good for second place in the National NOTE 2016 League West, 4.0 games behind the first-place Los Angeles Dodgers...the 2016 Series Record .............. 23-20-9 season marked the 10th time that the Dodgers and Giants finished in first and Series Record, home ..........13-7-6 second place (in either order) in the NL West...they also did so in 1971, 1994 Series Record, road ..........10-13-3 (strike-shortened season), 1997, 2000, 2003, 2004, 2012, 2014 and 2015. Series Openers ...............24-28 Series Finales ................29-23 OCTOBER BASEBALL: San Francisco advanced to the postseason for the Monday ...................... 7-10 fourth time in the last sevens seasons and for the 26th time in franchise history Tuesday ....................13-12 (since 1900), tied with the A's for the fourth-most appearances all-time behind Wednesday ..................10-15 the Yankees (52), Dodgers (30) and Cardinals (28)...it was the 12th postseason Thursday ....................12-5 appearance in SF-era history (since 1958). Friday ......................14-12 Saturday .....................17-9 Sunday .....................14-12 WILD CARD NOTES: The Giants and Mets faced one another in the one-game April .......................12-13 wild-card playoff, which was added to the MLB postseason in 2012...it was the May .........................21-8 second time the Giants played in this one-game playoff and the second time that June ...................... -

Jugador Y Mánager Exitoso; Miembro Del Recinto Sagrado Del Beisbol Mexicano

E D I T O R I A L José Ignacio Peña M. DIRECTORIO Tomás Alonso López R. Carla Bustamante José Ignacio Peña Molina Dr. Tomás Alonso López Ríos Edwin “Kako” Vázquez ([email protected]) SUB-DIRECTOR Jesús Alberto Rubio DIRECTOR GENERAL Alejandro Arellano D.G. Patrizio Caro Aragón Tony Menéndez L.I. Luis Gilberto Muñoz Haro ([email protected]) Priscilla Mungarro ADMINISTRADOR DISEÑO on el paso de los días, el béisbol de verano va acercándose a la Francisco Martínez recta final. COLABORADORES De hecho la Liga Mexicana de Beisbol ya está a menos de 15 días de Cllegar al final de su rol regular, dando entrada a los emocionantes play offs. Las Grandes Ligas ya iniciaron la segunda mitad, después del Juego de Estrellas. Todavía le queda mucha cuerda al mejor béisbol del mundo. En el clásico de media temporada, la Liga Nacional apaleó a la Americana 8- 0. Melky Cabrera fue nombrado el “Jugador más valioso” del encuentro CONTENIDO estelar. Por ello decidimos que fuera el pelotero de la portada de esta EL BATE DE PINKSTON LO HIZO INMORTAL 4 edición. LAS NUEVAS GENERACIONES (EXPOS) 6 FOTOS DEL RECUERDO 9 También, conforme avanza el verano, el béisbol de estufa de LMP se va JORGE FITCH 10 poniendo más caliente. Los movimientos en los equipos empiezan a volverse HERMOSILLO Y EL FORMATO DE SC 14 más intensos. GRANDES NOMBRES LATINOS EN GL 16 EL INICIO DE UN GRAN SUEÑO 19 Al celebrarse el draft de LMP, como nunca había sucedido, algunos equipos “EL CABALLO DE HIERRO”: LOU GEHRIG 20 se deshicieron de importantes peloteros veteranos para dar paso a la sangre TONY PÉREZ 25 joven. -

Article Title

General Admission Ragtime Baseball in New Orleans by S. Derby Gisclair Member, Society for American Baseball Research Ragtime was a new, syncopated music style born in the saloons and “sporting houses” of New Orleans’ Storyville district, an area named after city councilman Sidney Story, who in 1898 authored the legislation establishing the district. It was bounded by Iberville, Basin, St. Louis, and Robertson streets. At the same time that ragtime was gaining popularity throughout the South, the parallel popularity of the city’s professional baseball club, the New Orleans Pelicans, was gaining momentum as well. During the post-Civil War years the center of the baseball world in the South was New Orleans. The city boasted fifteen teams that had joined the National Association, the largest contingent from any southern city. Among these was an amateur team formed in 1865 known as the Pelicans. The city’s first professional team in 1887 as part of the Southern League, the Pelicans became a more stable enterprise in the reconstituted Southern Association that began play in 1901. The early Southern Association operated in a period in baseball known as the Deadball Era, so called primarily because of the type of ball used, but also because of the style of play at the time. It was a game which employed the General Admission scientific method – today known as “small ball” – bunts, hit an run plays, and base stealing. Hitters would choke up on their heavy wooden bats and would try to punch or slash a hit over the infield. Baseball entered the mainstream of the American cultural landscape in the early 20th century and the game’s popularity soared due to increased coverage in newspapers and periodicals. -

PHR Local Website Update 4-25-08

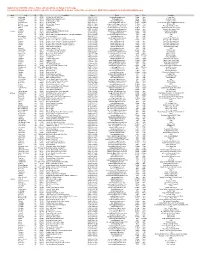

Updated as of 4/25/08 - Dates, Times and Locations are Subject to Change For more information or to confirm a specific local competition, please contact the Local Host or MLB PHR Headquarters at [email protected] State City ST Zip Local Host Phone Email Date Time Location Alaska Anchorage AK 99508 Mt View Boys & Girls Club (907) 297-5416 [email protected] 22-Apr 4pm Lions Park Anchorage AK 99516 Alaska Quakes Baseball Club (907) 344-2832 [email protected] 3-May Noon Kosinski Fields Cordova AK 99574 Cordova Little League (907) 424-3147 [email protected] 26-Apr 10am Volunteer Park Delta Junction AK 99737 Delta Baseball (907) 895-9878 [email protected] 6-May 4:30pm Delta Junction City Park HS Baseball Field Eielson AK 99702 Eielson Youth Program (907) 377-1069 [email protected] 17-May 11am Eielson AFB Elmendorf AFB AK 99506 3 SVS/SVYY (907) 868-4781 [email protected] 26-Apr 10am Elmendorf Air Force Base Nikiski AK 99635 NPRSA 907-776-8800x29 [email protected] 10-May 10am Nikiski North Star Elementary Seward AK 99664 Seward Parks & Rec (907) 224-4054 [email protected] 10-May 1pm Seward Little League Field Alabama Anniston AL 36201 Wellborn Baseball Softball for Youth (256) 283-0585 [email protected] 5-Apr 10am Wellborn Sportsplex Atmore AL 36052 Atmore Area YMCA (251) 368-9622 [email protected] 12-Apr 11am Atmore Area YMCA Atmore AL 36502 Atmore Babe Ruth Baseball/Atmore Cal Ripken Baseball (251) 368-4644 [email protected] TBD TBD TBD Birmingham AL 35211 AG Gaston -

Page 1.308.Indd

BOSTON RED SOX SPRING TRAINING GAME NOTES Boston Red Sox (2-5-1) at Baltimore Orioles (5-2) • 1:05 p.m. • Ed Smith Stadium, Sarasota, FL Boston Red Sox vs. Baltimore Orioles • 7:05 p.m. • JetBlue Park, Fort Myers, FL SPLITTING UP: The Red Sox and Orioles play split-squad THE CHAMPIONSHIP SEASON: The 2013 Red Sox led ON THE ROSTER: Boston has 58 games against each other today...They begin the day with a the AL and tied for the best record in MLB at 97-65 (.599) 1:05 p.m. contest at Ed Smith Stadium in Sarasota and play en route to the franchise’s 8th World Series Championship. players in Major League Spring Train- at JetBlue Park in Fort Myers at 7:05 p.m. ing Camp, including 18 non-roster The Red Sox won the deciding Game 6 of the 2013 invitees...The breakdown: 30 pitchers This is the 1st of 2 split-squad dates for the Red Sox... World Series over STL in Boston on 10/30, 120 days (11 invitees), 6 catchers (1 invitee), 13 They also split up on Tuesday (3/11) with a pair of 1:05 ago...It was the club’s 1st WS clinch at home in 95 p.m. games, with one back in Sarasota against the infi elders (5 invitees), and 9 outfi elders years, since Game 6 of the 1918 World Series at (1 invitee). Orioles and the other at home against the Marlins. Fenway Park (2-1 over CHC). CHECKING THE SLATE: Today’s contests vs. -

Page 1.311.Indd

BOSTON RED SOX SPRING TRAINING GAME NOTES Tuesday, March 11, 2014 Boston Red Sox (4-7-1) at Baltimore Orioles (9-2) • Ed Smith Stadium, Sarasota, FL Boston Red Sox (4-7-1) vs. Miami Marlins (7-3) • JetBlue Park, Fort Myers, FL CHECKING THE SLATE: Today’s contests at Baltimore THE CHAMPIONSHIP SEASON: The 2013 Red Sox led ON THE ROSTER: Boston has 58 and against the Rays are the Red Sox’ 13th and 14th of the AL and tied for the best record in MLB at 97-65 (.599) 31 Grapefruit League games over 30 days from 2/28-3/29. en route to the franchise’s 8th World Series Championship. players in Major League Spring Train- ing Camp, including 18 non-roster Today marks Boston’s last of 2 split-squad dates... The Red Sox won the deciding Game 6 of the 2013 invitees...The breakdown: 30 pitchers The Sox were swept in a day/night split-squad World Series over STL in Boston on 10/30, 120 days (11 invitees), 6 catchers (1 invitee), 13 doubleheader on Saturday at BAL’s Ed Smith Stadium ago...It was the club’s 1st WS clinch at home in 95 (7-3) and against BAL at JetBlue Park (13-2). infi elders (5 invitees), and 9 outfi elders years, since Game 6 of the 1918 World Series at (1 invitee). Tomorrow the Sox will enjoy the club’s only off-day of Fenway Park (2-1 over CHC). the spring. THREE OUT OF TEN: The Red Sox have won the World Se- HOW THEY WERE OBTAINED FACING THE O’S: Today’s game in Sarasota marks the 4th ries in 3 of the last 10 years -- 2004, 2007, 2013 -- following RED SOX 40-MAN ROSTER of 6 match-ups between these clubs this spring, with the an 86-year Championship drought...It marks the most titles Amateur Draft Picks (14): Bradley Sox taking 1 of their 1st 3 meetings...They will play next on among MLB teams in the new century. -

Asu/Sun Devil Softball Camps Softball Coaches Clinic

A 5153 85281- Tempe, AZ 2402 E.5 Sun DevilSoftballCamps,LLC ASU HOME GAMES ddress Correction Required 2008 th St.#1537 Feb 14 Western Kentucky ASU/SUN DEVIL Feb 15-17 Kajikawa Classic Feb 18 Southern Utah SOFTBALL CAMPS Feb 22-24 Littlewood Classic Feb 26 Canadian Olympic Team SOFTBALL Feb 29 March 1-2 Wilson/DeMarini Invitational March 4 Creighton COACHES CLINIC March 7-9 Diamond Devil Invitational March 13-15 Santa Clara March 25 Marshall April 11 UCLA April 12 Washington April 13 Washington January 18 – 19, 2008 April 15 UNLV Friday/Saturday April 18 Arizona April 19 Arizona April 25 Oregon State April 26 Oregon April 27 Oregon May 8 Stanford May 9 Cal May 10 Cal Group tickets are available for as low as $2.00 each. For more information about group tickets please contact Sarah Pavelko at: 480 727-7446 e mail [email protected] E mail: [email protected] Phone: 480 727 7312 GO DEVILS! Web site: www.freewebs.com/sdscamps/ www.thesundevils.com REGISTRATION Featured Speakers SCHEDULE Name FRIDAY JANUARY 18 Address Clint Myers- ASU Head Coach 4:00 – 6:00 Observe ASU Practice/ Registration Has guided the Sun Devils to a 107-32 City State Zip record and two consecutive trips to the 6:00 – 6:45 Hitting Fundamentals- Rob Wagner Phone Womens College World Series in his first 6:50 – 7:35 Pitching Fundamentals- Kirsten Voak two years. E-mail 7:40 – 8:25 Defense the ASU Way- Clint Myers Team/Organization Robert Wagner- ASU Assistant Coach 8:30 – 9:00 Panel Discussion- All Coaches Every season during his time at Utah, Make $175.00 check payable to Sun Washington and ASU his teams have 9:00 Coaches Social sponsored by Devil Softball Camps, LLC and return broken numerous school and NCAA hitting Pitching Essentials and Baseball Mental with this form to: th records. -

Analyzing the Parallelism Between the Rise and Fall of Baseball in Quebec and the Quebec Secession Movement Daniel S

Union College Union | Digital Works Honors Theses Student Work 6-2011 Analyzing the Parallelism between the Rise and Fall of Baseball in Quebec and the Quebec Secession Movement Daniel S. Greene Union College - Schenectady, NY Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses Part of the Canadian History Commons, and the Sports Studies Commons Recommended Citation Greene, Daniel S., "Analyzing the Parallelism between the Rise and Fall of Baseball in Quebec and the Quebec Secession Movement" (2011). Honors Theses. 988. https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses/988 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at Union | Digital Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Union | Digital Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Analyzing the Parallelism between the Rise and Fall of Baseball in Quebec and the Quebec Secession Movement By Daniel Greene Senior Project Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation Department of History Union College June, 2011 i Greene, Daniel Analyzing the Parallelism between the Rise and Fall of Baseball in Quebec and the Quebec Secession Movement My Senior Project examines the parallelism between the movement to bring baseball to Quebec and the Quebec secession movement in Canada. Through my research I have found that both entities follow a very similar timeline with highs and lows coming around the same time in the same province; although, I have not found any direct linkage between the two. My analysis begins around 1837 and continues through present day, and by analyzing the histories of each movement demonstrates clearly that both movements followed a unique and similar timeline. -

Scores, Statistics and Standings

SCORES, STATISTICS AND STANDINGS Scores, Statistics and Standings TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS .............................................................................................. 2 PRE-SCORING CHECKLIST ...................................................................................... 3 GAME SCORES* ....................................................................................................... 3 Add Game Scores ....................................................................................................................... 3 Edit Game Scores........................................................................................................................ 3 Delete Game Scores .................................................................................................................. 3 STATISTICS* ........................................................................................................... 4 Configure Statistics ................................................................................................................... 4 Update Program Sport Setting ....................................................................................................4 Enable/Disable Statistics ............................................................................................................4 Add Statistics ............................................................................................................................... 4 Edit Statistics .............................................................................................................................. -

Front Office Directory Brad Mohr

FRONT OfficE DIRECTORY Brad Mohr ................................................................................................ Manager, Baseball Operations Willie Jenks .................................................................................................Visiting Clubhouse Manager OFFICERS Steve Walters .......................................................................................... Coordinator, Ballpark Services Lawrence J. Dolan ................................................................................ Owner & Chief Executive Officer Gloria Carter ........................................................................................... Assistant, Ballpark Operations Paul J. Dolan ............................................................................................................................ President Kenny Campbell ...................................................................................................Main Lobby Reception Mark Shapiro ...................................................................... Executive Vice President, General Manager Louis Pavlick .......................................................................................................Maintenance/Custodial Dennis Lehman ................................................................................Executive Vice President, Business Ray Branham .......................................................................................................Maintenance/Custodial Victor Gregovits ....................................................................