Don Draper Lies, Cheats, and Steals, and We’Re Supposed to Be Okay with That?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mad Men Is MEN MAD MEN Unquestionably One of the Most Stylish, Sexy, and Irresistible Shows on Television

PHILOSOPHY/POP CULTURE IRWIN SERIES EDITOR: WILLIAM IRWIN EDITED BY Is DON DRAPER a good man? ROD CARVETH AND JAMES B. SOUTH What do PEGGY, BETTY, and JOAN teach us about gender equality? What are the ethics of advertising—or is that a contradiction in terms? M Is ROGER STERLING an existential hero? AD We’re better people than we were in the sixties, right? With its swirling cigarette smoke, martini lunches, skinny ties, and tight pencil skirts, Mad Men is MEN MAD MEN unquestionably one of the most stylish, sexy, and irresistible shows on television. But the series and PHILOSOPHY becomes even more absorbing once you dig deeper into its portrayal of the changing social and political mores of 1960s America and explore the philosophical complexities of its key Nothing Is as It Seems characters and themes. From Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle to John Kenneth Galbraith, Milton and Friedman, and Ayn Rand, Mad Men and Philosophy brings the thinking of some of history’s most powerful minds to bear on the world of Don Draper and the Sterling Cooper ad agency. You’ll PHILOSOPHY gain insights into a host of compelling Mad Men questions and issues, including happiness, freedom, authenticity, feminism, Don Draper’s identity, and more—and have lots to talk about the next time you fi nd yourself around the water cooler. ROD CARVETH is an assistant professor in the Department of Communications Media at Fitchburg State College. Nothing Is as It Seems Nothing Is as JAMES B. SOUTH is chair of the Philosophy Department at Marquette University. -

The Cross-Country/Cross-Class Drives of Don Draper/Dick Whitman: Examining Mad Men’S Hobo Narrative

Journal of Working-Class Studies Volume 2 Issue 1, 2017 Forsberg The Cross-Country/Cross-Class Drives of Don Draper/Dick Whitman: Examining Mad Men’s Hobo Narrative Jennifer Hagen Forsberg, Clemson University Abstract This article examines how the critically acclaimed television show Mad Men (2007- 2015) sells romanticized working-class representations to middle-class audiences, including contemporary cable subscribers. The television drama’s lead protagonist, Don Draper, exhibits class performatively in his assumed identity as a Madison Avenue ad executive, which is in constant conflict with his hobo-driven born identity of Dick Whitman. To fully examine Draper/Whitman’s cross-class tensions, I draw on the American literary form of the hobo narrative, which issues agency to the hobo figure but overlooks the material conditions of homelessness. I argue that the hobo narrative becomes a predominant but overlooked aspect of Mad Men’s period presentation, specifically one that is used as a technique for self-making and self- marketing white masculinity in twenty-first century U.S. cultural productions. Keywords Cross-class tensions; television; working-class representations The critically acclaimed television drama Mad Men (2007-2015) ended its seventh and final season in May 2015. The series covered the cultural and historical period of March 1960 to November 1970, and followed advertising executive Don Draper and his colleagues on Madison Avenue in New York City. As a text that shows the political dynamism of the mid-century to a twenty-first century audience, Mad Men has wide-ranging interpretations across critical camps. For example, in ‘Selling Nostalgia: Mad Men, Postmodernism and Neoliberalism,’ Deborah Tudor suggests that the show offers commitments to individualism through a ‘neoliberal discourse of style’ which stages provocative constructions of reality (2012, p. -

Examining Mad Men's Hobo Narrative

Journal of Working-Class Studies Volume 2 Issue 1, 2017 Forsberg The Cross-Country/Cross-Class Drives of Don Draper/Dick Whitman: Examining Mad Men’s Hobo Narrative Jennifer Hagen Forsberg, Clemson University Abstract This article examines how the critically acclaimed television show Mad Men (2007- 2015) sells romanticized working-class representations to middle-class audiences, including contemporary cable subscribers. The television drama’s lead protagonist, Don Draper, exhibits class performatively in his assumed identity as a Madison Avenue ad executive, which is in constant conflict with his hobo-driven born identity of Dick Whitman. To fully examine Draper/Whitman’s cross-class tensions, I draw on the American literary form of the hobo narrative, which issues agency to the hobo figure but overlooks the material conditions of homelessness. I argue that the hobo narrative becomes a predominant but overlooked aspect of Mad Men’s period presentation, specifically one that is used as a technique for self-making and self- marketing white masculinity in twenty-first century U.S. cultural productions. Keywords Cross-class tensions; television; working-class representations The critically acclaimed television drama Mad Men (2007-2015) ended its seventh and final season in May 2015. The series covered the cultural and historical period of March 1960 to November 1970, and followed advertising executive Don Draper and his colleagues on Madison Avenue in New York City. As a text that shows the political dynamism of the mid-century to a twenty-first century audience, Mad Men has wide-ranging interpretations across critical camps. For example, in ‘Selling Nostalgia: Mad Men, Postmodernism and Neoliberalism,’ Deborah Tudor suggests that the show offers commitments to individualism through a ‘neoliberal discourse of style’ which stages provocative constructions of reality (2012, p. -

Mad Men, Episode 10, "Hands & Knees" Tim Anderson Old Dominion University, [email protected]

Old Dominion University ODU Digital Commons Communication & Theatre Arts Faculty Communication & Theatre Arts Publications 9-29-2010 "Listen. Do You Want to Know a Secret?": Mad Men, Episode 10, "Hands & Knees" Tim Anderson Old Dominion University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/communication_fac_pubs Part of the Television Commons Repository Citation Anderson, Tim, ""Listen. Do You Want to Know a Secret?": Mad Men, Episode 10, "Hands & Knees"" (2010). Communication & Theatre Arts Faculty Publications. 27. https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/communication_fac_pubs/27 Original Publication Citation Anderson, T. (2010, September 29). "Listen. Do you want to know a secret?": Mad Men, episode 10, "Hands & Knees" [Blog post]. Retrieved from http://blog.commarts.wisc.edu/2010/09/29/listen-do-you-want-to-know-a-secret-mad-men-episode-10-hands- knees/ This Blog is brought to you for free and open access by the Communication & Theatre Arts at ODU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Communication & Theatre Arts Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of ODU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “Listen. Do You Want to Know a Secret?”: Mad Men, Episode 10, “Hands & Knees” September 29, 2010 By Tim Anderson | The most striking use of pop music in this season of Mad Men appears at the beginning of episode eight, “The Summer Man”. Opening with a montage of Don Draper after he has begun to reclaim his life we hear The Rolling Stones 1965 summer release, “(I can’t get no) Satisfaction”. Arguably their signature song of the 1960s, the Stones’ three minutes and forty four seconds of audible discontent is layered onto a somewhat rehabilitated Draper who swims and takes on writing exercises. -

Stoneback Thesis.Pdf

“Women Usually Want to Please”: A Linguistic Analysis of Femininity and Power in Mad Men by Stephanie Stoneback A thesis presented for the B.A. degree with Honors in The Department of English University of Michigan Winter 2019 © 2019 Stephanie Christine Stoneback To my mom. Acknowledgments First of all, I would like to thank my thesis advisor, Anne Curzan, for her unwavering support, guidance, and understanding throughout this process. Anne, without your encouragement, listening ear, criticism, and patience, I would have never been able to produce such exciting analysis that I am proud of. To me, you embody what it means to be a powerful woman and you are such an inspiration as I complete my undergraduate work and enter a new phase of life. Thank you so much for that. Next, I must thank our program director, Adela Pinch, for her helpful tips and constant reminders that everything was going to be okay. Adela, in many ways, you have shaped my education as an English major at the University of Michigan—you taught me the Introduction to Literary Studies course, a course on Jane Austen, and both semesters of Thesis Writing. Thank you so much for the years of engaged learning, critical thinking, and community building. I would also like to thank some of the staff members of the New England Literature Program, who helped instill in me a confidence in my writing and in my self that I never knew I was capable of. Aric Knuth, Ryan Babbitt, Mark Gindi, Maya West, and Kristin Gilger, each of you had a distinct and lasting impact on me, in some unspoken and perhaps sacred ways. -

The Three Faces of Mad Men

Cultural Studies Review volume 18 number 2 September 2012 http://epress.lib.uts.edu.au/journals/index.php/csrj/index pp. 151–68 Melissa Jane Hardie 2012 The Three Faces of Mad Men Middlebrow Culture and Quality Television MELISSA JANE HARDIE UNIVERSITY OF SYDNEY —THE REJUVENATOR An association between pleasure and the machine anchors the eleventh episode of Mad Men’s first season. Peggy Olsen is tasked with writing copy for a weight-loss contraption (the Rejuvenator) that she discovers operates more efficiently as a vibrator. A distant goal of reduction is supplanted by a more immediate satisfaction and amplification. Her slogan, ‘You’ll Love the Way It Makes You Feel’, alludes to the potential for pleasure the Rejuvenator holds, substituting feeling, and positive feelings at that, for the purported function of the device, streamlining the disciplinary regime of bodily reduction. The Rejuvenator models temporal reversion as the euphemistic pretext for self-pleasure: rejuvenation re-engineers a nostalgic version of the past as a future event. Within the parameters of a period drama this modelling has the collateral effect of demarcating Mad Men’s modus operandi as typically modernist, a utopian streamlining of history with incidental benefit for current pleasures. At the same time it offers a frame for the series itself as a form of nostalgic revision that pits ISSN 1837-8692 representations of the sluggish or reactionary past against its own modernising propaganda. It introduces feminine sexual pleasure as a metonym for the aesthetic, identifying another concern mid-century, the market dominance of certain kinds of women’s texts, and instating an allegory for the contemporary place of twenty-first century ‘quality’ television and shows like Mad Men as rejuvenated forms of the pleasing bestseller. -

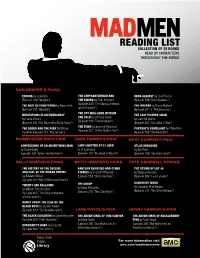

Reading List Collection of 25 Books Read by Characters Throughout the Series

READING LIST COLLECTION OF 25 BOOKS READ BY CHARACTERS THROUGHOUT THE SERIES DON DRAPER’S PICKS EXODUS by Leon Uris THE CHRYSANTHEMUM AND ODDS AGAINST by Dick Francis (Episode 106 “Babylon”) THE SWORD by Ruth Benedict (Episode 509 “Dark Shadows”) (Episode 405 “The Chrysanthemum THE BEST OF EVERYTHING by Rona Jaffe THE INFERNO by Dante Alighieri and the Sword”) (Episode 106 “Babylon”) (Episode 601-2 “The Doorway”) THE SPY WHO CAME IN FROM MEDITATIONS IN AN EMERGENCY THE LAST PICTURE SHOW by John Le Carre by Frank O’Hara THE COLD by Larry McMurtry (Episode 413 “Tomorrowland”) (Episode 201 “For Those Who Think Young”) (Episode 607 “Man With a Plan”) THE FIXER by Bernard Malamud THE SOUND AND THE FURY by William PORTNOY’S COMPLAINT by Philip Roth (Episode 507 “At the Codfish Ball”) Faulkner (Episode 211 “The Jet Set”) (Episode 704 “The Monolith”) ROGER STERLING’S PICK JOAN HARRIS’S PICK BERT COOPER’S PICK CONFESSIONS OF AN ADVERTISING MAN LADY CHATTERLEY’S LOVER ATLAS SHRUGGED by David Ogilvy D. H. Lawrence by Ayn Rand (Episode 307 “Seven Twenty Three”) (Episode 103 "Marriage of Figaro") (Episode 108 “The Hobo Code”) SALLY DRAPER’S PICKS BETTY DRAPER’S PICKS PETE CAMPBELL’S PICKS THE HISTORY OF THE DECLINE BABYLON REVISITED AND OTHER THE CRYING OF LOT 49 AND FALL OF THE ROMAN EMPIRE STORIES by F. Scott Fitzgerald by Thomas Pynchon by Edward Gibbon (Episode 204 “Three Sundays”) (Episode 508 “Lady Lazarus”) (Episode 303 “My Old Kentucky Home”) GOODNIGHT MOON TWENTY ONE BALLOONS THE GROUP by Mary McCarthy by Margaret Wise Brown by William Pene -

What Are Your Ex-Employees Taking with Them? Publication 3.13.13

What Are Your Ex-Employees Taking with Them? Publication 3.13.13 Decades ago, it was reasonable to imagine that one could work for the same company from the start of one’s career to the end. Think about the world portrayed in Mad Men. Don Draper has mostly worked with the same fictional co-workers – Roger Sterling, Pete Campbell, Joan Harris, Bert Cooper, etc. – for the better part of a decade. This is not just a function of Matthew Weiner keeping the same actors around; it’s a relatively accurate portrayal of work in the 1960s. Times are different now. Workers change jobs (and often careers) with far more regularity than they did in the years following World War II. Medical practices are no different. They experience turnover just like other businesses. Each time an employee leaves – whether voluntarily or otherwise – he or she can depart with valuable information and patient relationships. The higher an employee’s perch in a practice, the more likely it is that he or she can go to a competitor and move patients in the process. Thus, the prudent medical practice decision-maker prepare for this possibility. The advice that you give patients on the proverbial ounce of prevention applies just as much to taking steps to prevent employees from taking your confidential information and patient relationships when they leave. Here are some best practices to follow before and immediately after an employee defects: 1. Have agreements in place 2. Think through your key information and take steps to protect it 3. Make clear that employees cannot misuse the practice’s computer system 4. -

Matthew Weiner's Mad

EXHIBITION FACT SHEET Matthew Weiner’s Mad Men March 14–September 6, 2015 (third-floor changing exhibitions gallery) Overview This new exhibition, about the creative process behind the television series Mad Men, features large-scale sets, memorable costumes, hundreds of props, advertising art used in the production of the series, and personal notes and research material from Matthew Weiner, the show’s creator, head writer, and executive producer. The exhibition offers unique insight into the series’ origins, and how its exceptional storytelling and remarkable attention to period detail resulted in a vivid portrait of an era and the characters who lived through it. Matthew Weiner’s Mad Men marks the first time objects relating to the production of the series will be shown in public on this scale. The exhibition was accompanied by a film series, Required Viewing: Mad Men’s Movie Influences, which featured ten films selected by Matthew Weiner that inspired the show. It ran March 14 through April 26, 2015. The exhibition coincides with the series’ final seven episodes, which aired on AMC from April 5–May 17, 2015. Highlights include: Two large-scale sets, including Don Draper’s SC&P office and the Draper family kitchen from their Ossining home. These sets were transported from Los Angeles where Mad Men was shot, and installed at the Museum using the original props from the show. Ellen Freund, who served as property master on Mad Men for seasons four through seven, dressed the sets for the Museum’s installation. A recreation of the writers’ room where Weiner and his team crafted story ideas and scripts for the series, complete with story notes for the first half of season seven listed on a white board, and index cards, research material, and other elements created and used by Mad Men’s writers. -

ENG 1131: Writing About American Prestige TV (Sec 4841)

ENG 1131: Writing About American Prestige TV (sec 4841) Milt Moise MWF/R: Period 4: 10:40-11:30; E1-E3: 7:20-10:10 Classroom: WEIL 408E Office Hours: W, R Per. 7-8, or by appointment, TUR 4342 Course Website: CANVAS Instructor Email: [email protected] Twitter account: @milt_moise Course Description, Objectives, and Outcomes: This course examines the emergence of what is now called “prestige TV,” and the discourse surrounding it. Former FCC chairman Newton N. Minow, in a 1961 speech, once called TV “a vast wasteland” of violence, formulaic entertainment, and commercials. Television has come a long way since then, and critics such as Andy Greenwald now call our current moment of television production “the golden age of TV.” While television shows containing the elements Minow decried decades ago still exist, alongside them we now find television characterized by complex plots, moral ambiguity, excellent production value, and outstanding writing and acting performances. In this class, our discussions will center around, but not be limited to the aesthetics of prestige TV, and how AMC’s Mad Men and TBS’s Search Party conform to or subvert this framework. Students will learn to visually analyze a television show, and develop their critical reading and writing skills. By the end of the semester, students will be able to make substantiated arguments about the television show they have seen, and place it into greater social and historical context. They will also learn how to conduct formal research through the use of secondary sources and other relevant material to support their theses, analyses and arguments. -

Mad Men: Study of the Show "Mad Men" and Its Influence on Retro-Sexism in Advertising and Media

InPrint Volume 2 Issue 1 June, 2013 Article 9 2013 The World of Mad Men: Study of the Show "Mad Men" and its Influence on Retro-Sexism in Advertising and Media Michaela Hordyniec Follow this and additional works at: https://arrow.tudublin.ie/inp Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Hordyniec, Michaela (2013) "The World of Mad Men: Study of the Show "Mad Men" and its Influence on Retro-Sexism in Advertising and Media," InPrint: Vol. 2: Iss. 1, Article 9. Available at: https://arrow.tudublin.ie/inp/vol2/iss1/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Ceased publication at ARROW@TU Dublin. It has been accepted for inclusion in InPrint by an authorized administrator of ARROW@TU Dublin. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 4.0 License The world of Mad Men Study of the show Mad Men and its influence on retro-sexism in advertising and media Michaela Hordyniec “Sexism in advertising. It sounds almost quaint. The very words have a retro ring to them, conjuring up, on the one hand, scenes of be-aproned housewives serving casseroles to hungry husbands, and on the other, posters of leggy models in platform boots and hotpants with—and this is a key image in the scenario—feminists in dungarees slapping ‘this degrades women’ stickers all over them. For sexism isn’t just a phenomenon, it’s an idea: and has no currency as such without people who actually hold it, discuss it and apply it. -

Race, Religion, and Rights: Otherness Gone Mad Tracy Lucht Iowa State University, [email protected]

Journalism Publications Greenlee School of Journalism and Communication 2014 Race, Religion, and Rights: Otherness Gone Mad Tracy Lucht Iowa State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/jlmc_pubs Part of the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Gender, Race, Sexuality, and Ethnicity in Communication Commons, History of Gender Commons, Journalism Studies Commons, Social History Commons, United States History Commons, and the Women's History Commons The ompc lete bibliographic information for this item can be found at http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ jlmc_pubs/4. For information on how to cite this item, please visit http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ howtocite.html. This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the Greenlee School of Journalism and Communication at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journalism Publications by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Race, Religion, and Rights: Otherness Gone Mad Abstract Inevitable yet often unnamed, the looming political radicalism of the late 1960s acts as something like a silent partner in the Mad Men narrative, relying on viewers' historical knowledge of the social tension outside Sterling Cooper to underscore the contrived nature of the world within it. Just as the series spans the period between the emergence of liberal and radical white feminist discourses, it also bridges key moments in the civil rights movement, from the boycotts, otv er registration drives, and sweeping oratory of the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., to the assassinations of civil rights leaders and activists; rioting in Watts nda other cities; and the emergence of a black power movement.