Linguistics 101 Language Acquisition Language Acquisition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Second Language Acquisition Through Neurolinguistic Programming: a Psychoanalytic Approach

International Journal of Engineering & Technology, 7 (4.36) (2018) 624-629 International Journal of Engineering & Technology Website: www.sciencepubco.com/index.php/IJET Research paper Second Language Acquisition Through Neurolinguistic Programming: A Psychoanalytic Approach A. Delbio1*, M. Ilankumaran2 1Research Scholar in English, Noorul Islam Centre for Higher Education, Kumaracoil. 2Professor of English, Noorul Islam Centre for Higher Education, Kumaracoil, Thuckalay, Tamilnadu, India. E-mail:[email protected] *Corresponding author E-mail: [email protected] Abstract English is the only lingua-franca for the whole world in present age of globalization and liberalization. English language is considered as an important tool to acquire a new and technical information and knowledge. In this situation English learners and teachers face a lot of problems psychologically. Neuro linguistic studies the brain mechanism and the performance of the brain in linguistic competences. The brain plays a main role in controlling motor and sensory activities and in the process of thinking. Studies regarding development of brain bring some substantiation for psychological and anatomical way of language development. Neuro-Linguistic Programming (NLP) deals with psychological and neurological factors. It also deals with the mode of brain working and the way to train the brain to achieve the purpose. Many techniques are used in the NLP. It improves the fluency and accuracy in target language. It improves non-native speaker to improve the LSRW skills. This paper brings out the importance of the NLP in language learning and teaching. It also discusses the merits and demerits of the NLP in learning. It also gives the solution to overcome the problems and self-correction is motivated through neuro-linguistic programming. -

Statistical Language Learning: Learning-Oriented Theories Is That Mechanisms and Constraints Such Accounts Seem at Odds with One of the Central Observations 1 Jenny R

110 VOLUME 12, NUMBER 4, AUGUST 2003 most important arguments against Statistical Language Learning: learning-oriented theories is that Mechanisms and Constraints such accounts seem at odds with one of the central observations 1 Jenny R. Saffran about human languages. The lin- Department of Psychology and Waisman Center, University of Wisconsin–Madison, guistic systems of the world, de- Madison, Wisconsin spite surface differences, share deep similarities, and vary in non- arbitrary ways. Theories of language Abstract guage, it seems improbable that chil- acquisition that focus primarily on What types of mechanisms dren could ever discern its structure. preexisting knowledge of language underlie the acquisition of hu- The process of acquiring such a sys- do provide an elegant explanation man language? Recent evidence tem is likely to be nearly as com- for cross-linguistic similarities. suggests that learners, includ- plex as the system itself, so it is not Such theories, which are exempli- ing infants, can use statistical surprising that the mechanisms un- fied by the seminal work of Noam properties of linguistic input to derlying language acquisition are a Chomsky, suggest that linguistic uni- discover structure, including matter of long-standing debate. One versals are prespecified in the child’s sound patterns, words, and the of the central focuses of this debate linguistic endowment, and do not re- beginnings of grammar. These concerns the innate and environ- quire learning. Such accounts gener- abilities appear to be both pow- mental contributions to the lan- ate predictions about the types of erful and constrained, such that guage-acquisition process, and the patterns that should be observed some statistical patterns are degree to which these components cross-linguistically, and lead to im- more readily detected and used draw on information and abilities portant claims regarding the evolu- than others. -

Language Acquisition Device and the Origin of Language Briana Sobecks

Language Acquisition Device and the Origin of Language Briana Sobecks In the early twentieth century, psychologists re- a particular language, the universal grammar can be refined alized that language is not just understanding words, but to fit a specific language. Even if some children may hear a also requires learning grammar, syntax, and semantics. specific language pattern more than others, the fact that all Modern language is incredibly complex, but young chil- children know it indicates a poss ble innate language sense. dren can understand it remarkably well. This idea supports One of Chomsky’s main tenants in his LAD theory Chomsky’s idea that language learning is innate. According is the Poverty of Stimulus argument. Though children do to his hypothesis, young children receive “primary linguistic collect data to learn a language, it is unlikely that the data data” from what is spoken around them, which helps them they are exposed to is enough to master an entire lan- develop knowledge of that specific language (Cowie 2008). guage. Instead, they must infer grammatical rules through Children passively absorb language from adults, peers, an internal sense. There are several cognitive factors that and exposure to media. However, this data is not sufficient support this argument. Underdetermination states that the to explain how children can learn unique constructions finite data is applicable in infinite situations. In context, of words and grammar patterns. Previously structuralists this means that children utilize the finite amount of data created a list of “phrase structure rules” to generate all they hear to generate any possible sentence. -

Similarities and Differences Between Simultaneous and Successive Bilingual Children: Acquisition of Japanese Morphology

International Journal of Applied Linguistics & English Literature E-ISSN: 2200-3452 & P-ISSN: 2200-3592 www.ijalel.aiac.org.au Similarities and Differences between Simultaneous and Successive Bilingual Children: Acquisition of Japanese Morphology Yuki Itani-Adams1, Junko Iwasaki2, Satomi Kawaguchi3* 1ANU College of Asia & the Pacific, The Australian National University, Canberra, ACT, 2601, Australia 2School of Arts and Humanities, Edith Cowan University, 2 Bradford Street, Mt Lawley WA 6050, Australia 3School of Humanities and Communication Arts, Western Sydney University, Bullecourt Ave, Milperra NSW 2214, Australia Corresponding Author: Satomi Kawaguchi , E-mail: [email protected] ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history This paper compares the acquisition of Japanese morphology of two bilingual children who had Received: June 14, 2017 different types of exposure to Japanese language in Australia: a simultaneous bilingual child Accepted: August 14, 2017 who had exposure to both Japanese and English from birth, and a successive bilingual child Published: December 01, 2017 who did not have regular exposure to Japanese until he was six years and three months old. The comparison is carried out using Processability Theory (PT) (Pienemann 1998, 2005) as a Volume: 6 Issue: 7 common framework, and the corpus for this study consists of the naturally spoken production Special Issue on Language & Literature of these two Australian children. The results show that both children went through the same Advance access: September 2017 developmental path in their acquisition of the Japanese morphological structures, indicating that the same processing mechanisms are at work for both types of language acquisition. However, Conflicts of interest: None the results indicate that there are some differences between the two children, including the rate Funding: None of acquisition, and the kinds of verbal morphemes acquired. -

A Linguistic Perspective on the Acquisition of German As an L2

i A Linguistic Perspective on the Acquisition of German as an L2 A thesis submitted to the Miami University Honors Program in partial fulfillment of the requirements for University Honors with Distinction by Nicholas D. Stoller (December 2006) Oxford, Ohio ii ABSTRACT A LINGUISTIC PERSPECTIVE ON THE ACQUISITION OF GERMAN AS AN L2 by Nicholas D. Stoller It is obvious that the setting of acquisition, the amount and type of input, and the motivation of learners play a large role in adult second language (L2) acquisition. Many of the theories of L2 acquisition unfortunately fail to adequately take these variables into account. This thesis gives an overview of the current and past theories, including evidence for and against each theory. This is supplemented by an error analysis of second year Miami University students to see if this can give support to any of the current theories. Once that is completed, I examine the relation between input and the possibility of a language learning device such as UG and then move on to pedagogical application of my findings. iii Contents Chapter Page 1 Introduction 1 2 2 The Basis of the Study of L2 Acquisition 2 3 Linguistic Theories of L2 Acquisition 7 3.1 Theories without UG 7 3.1.1 Contrastive Analysis Hypothesis 7 3.1.2 Markedness Difference Hypothesis 8 3.1.3 Fundamental Difference Hypothesis 9 3.1.4 Information Processing Approach 10 3.2 Theories with Partial UG 13 3.2.1 Transfer Hypothesis 13 3.2.2 Krashen’s Comprehension Hypothesis 14 3.3 Theories with Full UG use 19 3.3.1 Identity Hypothesis 19 3.3.2 Full Transfer/Full Access Hypothesis 20 3.4 Overview of the Theories 21 4 Error Analysis and Miami University 2nd 22 Year Students 4.1 Errors of Cases Following Verbs 23 4.2 Errors of Gender of Nouns 25 4.3 Errors of Verb Form 26 4.4 Errors of Umlaut Usage 29 5 Relation of UG and Input 30 6.1 Problems with Input in Classroom Instruction 33 6.2 Pedagogy and L2 Acquisition 35 7 Conclusion 40 Bibliography 42 iv 1 A Linguistic Perspective on the Acquisition of German as an L2 1. -

Part 1: Introduction to The

PREVIEW OF THE IPA HANDBOOK Handbook of the International Phonetic Association: A guide to the use of the International Phonetic Alphabet PARTI Introduction to the IPA 1. What is the International Phonetic Alphabet? The aim of the International Phonetic Association is to promote the scientific study of phonetics and the various practical applications of that science. For both these it is necessary to have a consistent way of representing the sounds of language in written form. From its foundation in 1886 the Association has been concerned to develop a system of notation which would be convenient to use, but comprehensive enough to cope with the wide variety of sounds found in the languages of the world; and to encourage the use of thjs notation as widely as possible among those concerned with language. The system is generally known as the International Phonetic Alphabet. Both the Association and its Alphabet are widely referred to by the abbreviation IPA, but here 'IPA' will be used only for the Alphabet. The IPA is based on the Roman alphabet, which has the advantage of being widely familiar, but also includes letters and additional symbols from a variety of other sources. These additions are necessary because the variety of sounds in languages is much greater than the number of letters in the Roman alphabet. The use of sequences of phonetic symbols to represent speech is known as transcription. The IPA can be used for many different purposes. For instance, it can be used as a way to show pronunciation in a dictionary, to record a language in linguistic fieldwork, to form the basis of a writing system for a language, or to annotate acoustic and other displays in the analysis of speech. -

Whole Language Instruction Vs. Phonics Instruction: Effect on Reading Fluency and Spelling Accuracy of First Grade Students

Whole Language Instruction vs. Phonics Instruction: Effect on Reading Fluency and Spelling Accuracy of First Grade Students Krissy Maddox Jay Feng Presentation at Georgia Educational Research Association Annual Conference, October 18, 2013. Savannah, Georgia 1 Abstract The purpose of this study is to investigate the efficacy of whole language instruction versus phonics instruction for improving reading fluency and spelling accuracy. The participants were the first grade students in the researcher’s general education classroom of a non-Title I school. Stratified sampling was used to randomly divide twenty-two participants into two instructional groups. One group was instructed using whole language principles, where the children only read words in the context of a story, without any phonics instruction. The other group was instructed using explicit phonics instruction, without a story or any contextual influence. After four weeks of treatment, results indicate that there were no statistical differences between the two literacy approaches in the effect on students’ reading fluency or spelling accuracy; however, there were notable changes in the post test results that are worth further investigation. In reading fluency, both groups improved, but the phonics group made greater gains. In spelling accuracy, the phonics group showed slight growth, while the whole language scores decreased. Overall, the phonics group demonstrated greater growth in both reading fluency and spelling accuracy. It is recommended that a literacy approach should combine phonics and whole language into one curriculum, but place greater emphasis on phonics development. 2 Introduction Literacy is the fundamental cornerstone of a student’s academic success. Without the skill of reading, children will almost certainly have limited academic, economic, social, and even emotional success in school and in later life (Pikulski, 2002). -

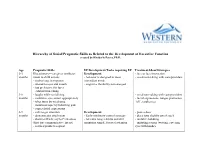

Hierarchy of Social/Pragmatic Skills As Related to the Development of Executive Function Created by Kimberly Peters, Ph.D

Hierarchy of Social/Pragmatic Skills as Related to the Development of Executive Function created by Kimberly Peters, Ph.D. Age Pragmatic Skills EF Development/Tasks requiring EF Treatment Ideas/Strategies 0-3 Illocutionary—caregiver attributes Development: - face to face interaction months intent to child actions - behavior is designed to meet - vocal-turn-taking with care-providers - smiles/coos in response immediate needs - attends to eyes and mouth - cognitive flexibility not emerged - has preference for faces - exhibits turn-taking 3-6 - laughs while socializing - vocal turn-taking with care-providers months - maintains eye contact appropriately - facial expressions: tongue protrusion, - takes turns by vocalizing “oh”, raspberries. - maintains topic by following gaze - copies facial expressions 6-9 - calls to get attention Development: - peek-a-boo months - demonstrates attachment - Early inhibitory control emerges - place toys slightly out of reach - shows self/acts coy to Peek-a-boo - tolerates longer delays and still - imitative babbling (first true communicative intent) maintains simple, focused attention - imitating actions (waving, covering - reaches/points to request eyes with hands). 9-12 - begins directing others Development: - singing/finger plays/nursery rhymes months - participates in verbal routines - Early inhibitory control emerges - routines (so big! where is baby?), - repeats actions that are laughed at - tolerates longer delays and still peek-a-boo, patta-cake, this little piggy - tries to restart play maintain simple, -

Linguistic Scaffolds for Writing Effective Language Objectives

Linguistic Scaffolds for Writing Effective Language Objectives An effectively written language objective: • Stems form the linguistic demands of a standards-based lesson task • Focuses on high-leverage language that will serve students in other contexts • Uses active verbs to name functions/purposes for using language in a specific student task • Specifies target language necessary to complete the task • Emphasizes development of expressive language skills, speaking and writing, without neglecting listening and reading Sample language objectives: Students will articulate main idea and details using target vocabulary: topic, main idea, detail. Students will describe a character’s emotions using precise adjectives. Students will revise a paragraph using correct present tense and conditional verbs. Students will report a group consensus using past tense citation verbs: determined, concluded. Students will use present tense persuasive verbs to defend a position: maintain, contend. Language Objective Frames: Students will (function: active verb phrase) using (language target) . Students will use (language target) to (function: active verb phrase) . Active Verb Bank to Name Functions for Expressive Language Tasks articulate defend express narrate share ask define identify predict state compose describe justify react to summarize compare discuss label read rephrase contrast elaborate list recite revise debate explain name respond write Language objectives are most effectively communicated with verb phrases such as the following: Students will point out similarities between… Students will express agreement… Students will articulate events in sequence… Students will state opinions about…. Sample Noun Phrases Specifying Language Targets academic vocabulary complete sentences subject verb agreement precise adjectives complex sentences personal pronouns citation verbs clarifying questions past-tense verbs noun phrases prepositional phrases gerunds (verb + ing) 2011 Kate Kinsella, Ed.D. -

Linguistics As a Resouvce in Language Planning. 16P

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 095 698 FL 005 720 AUTHOR Garvin, Paul L. TITLE' Linguistics as a Resouvce in Language Planning. PUB DATE Jun 73 NOTE 16p.; PaFPr presented at the Symposium on Sociolinguistics and Language Planning (Mexico City, Mexico, June-July, 1973) EPRS PPICE MF-$0.75 HC-$1.50 PLUS POSTAGE DESCRIPTORS *Applied Linguistics; Language Development; *Language Planning; Language Role; Language Standardization; Linguistics; Linguistic Theory; Official Languages; Social Planning; *Sociolinguistics ABSTPACT Language planning involves decisions of two basic types: those pertaining to language choice and those pertaining to language development. linguistic theory is needed to evaluate the structural suitability of candidate languages, since both official and national languages mast have a high level of standardizaticn as a cultural necessity. On the other hand, only a braodly conceived and functionally oriented linguistics can serve as a basis for choosiag one language rather than another. The role of linguistics in the area of language development differs somewhat depending on whether development is geared in a technological and scientific or a literary, artistic direction. In the first case, emphasis is on the development of terminologies, and in the second case, on that of grammatical devices and styles. Linguistics can provide realistic and practical arguments in favor of language development, and a detailed, technical understanding of such development, as well as methodological skills. Linguists can and must function as consultants to those who actually make decisions about language planning. For too long linguists have pursued only those aims generated within their own field. They must now broaden their scope to achieve the kind of understanding of language that is necessary for a productive approach to concrete language problems. -

New Paradigm for the Study of Simultaneous V. Sequential Bilingualism

New Paradigm for the Study of Simultaneous v. Sequential Bilingualism Suzanne Flynn1, Claire Foley1 and Inna Vinnitskaya2 1MIT and 2University of Ottawa 1. Introduction Mastering multiple languages is a commonplace linguistic achievement for most of the world’s population. Chomsky (in Mukherji et al. 2000) notes that “In most of human history and in most parts of the world today, children grow up speaking a variety of languages…” Clearly, multilingualism “is just a natural state of the human mind.” Notably, most of this language learning occurs in untutored, naturalistic settings and throughout the lifespan of an individual. The false sense of language homogeneity and monolingualism that is often heralded in the United States, at least in certain regional sections, is clearly a historical artifact. As Chomsky notes: Even in the United States the idea that people speak one language is not true. Everyone grows up hearing many different languages. Sometimes they are called “dialects or stylistic variants or whatever” but they are really different languages. It is just that they are so close to each other that we don’t bother calling them different languages (Chomsky, in Mukherji et al., 2000:19 ) A conclusion is that every individual, by virtue of living within a community, is bilingual1 in some sense. Further, this means that in the same sense there is essentially universal multilingualism in the world. Despite the centrality of multilingualism to the human experience, however, questions persist concerning how learners construct new language -

1 the Story of Language Acquisition: from Words to World and Back

The story of language acquisition: From words to world and back again Amy Pace Temple University Dani F. Levine Temple University Giovanna Morini University of Delaware Kathy Hirsh-Pasek Temple University Roberta Michnick Golinkoff University of Delaware Pace, A., Levine, D., Morini, G., Hirsh-Pasek, K. & Golinkoff, R.M. (2016) The story of language acquisition: From words to world and back again. In L. Balter and C. Tamis-LeMonda C. (Eds.), Child Psychology: A Handbook of Contemporary Issues, 3rd Edition. 43-79. 1 Introduction Imagine an infant visiting the zoo with her mother. From her stroller, she observes a troop of capuchins on a nearby tree. Her mother points to the scene and says, “Look! The monkeys are grooming each other!” How might she come to understand that her mother’s arbitrary auditory signals represent something about a scene that she is witnessing? How does she parse the continuous actions of the apes to derive appropriate units of meaning such as agents or actions from this complex, dynamic event? And how might she make the correct assumptions about how the words relate to the unfolding events before her? Despite recent advances, much of the current debate centers on the classical questions of how infants map words onto the dazzling array of sights and sounds in their world and how this process is guided by development and experience. Indeed, the field is still pondering the classic gavagai story that was introduced in 1960 by Quine. Given the complexity of the world, how is a language learner to know that the foreign word gavagai uttered while a rabbit scurries by, refers to the entire rabbit rather than to the fur, ears, or ground on which it thumps.