Flooded Jellyskin (Leptogium Rivulare)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Red List of Estonian Lichens: Revision in 2019

Folia Cryptog. Estonica, Fasc. 56: 63–76 (2019) https://doi.org/10.12697/fce.2019.56.07 Red List of Estonian lichens: revision in 2019 Piret Lõhmus1, Liis Marmor2, Inga Jüriado1, Ave Suija1,3, Ede Oja1, Polina Degtjarenko1,4, Tiina Randlane1 1University of Tartu, Institute of Ecology and Earth Sciences, Lai 40, 51005 Tartu, Estonia. E-mail: [email protected] 2E-mail: [email protected] 3University of Tartu, Natural History Museum, Vanemuise 46, 51014 Tartu, Estonia 4Swiss Federal Research Institute WSL, Biodiversity and Conservation Biology, Zürcherstrasse 111, 8903 Birmensdorf, Switzerland Abstract: The second assessment of the threat status of Estonian lichens based on IUCN system was performed in 2019. The main basis for choosing the species to be currently assessed was the list of legally protected lichens and the list of species assigned to the Red List Categories RE–DD in 2008. Species that had been assessed as Least Concern (LC) in 2008 were not evaluated. Altogether, threat status of 229 lichen species was assessed, among them 181 were assigned to the threatened categories (CR, EN, VU), while no species were assigned to the LC category. Compared to the previous red list, category was deteriorated for 58% and remained the same for 32% of species. In Estonia, threatened lichens inhabit mainly forests (particularly dry boreal and nemoral deciduous stands), alvar grasslands, sand dunes and various saxicolous habitats. Therefore, the most frequent threat factors were forest cutting and overgrowing of alvars and dunes (main threat factor for 96 and 70 species, respectfully). Kokkuvõte: 2019. aastal viidi läbi teistkordne IUCN süsteemil põhinev Eesti samblike ohustatuse hindamine. -

Leptogium Teretiusculum Species Fact Sheet

SPECIES FACT SHEET Common Name: shrubby vinyl Scientific Name: Leptogium teretiusculum (Wallr.) Arnold Division: Ascomycota Class: Ascomycetes Order: Lecanorales Family: Collemataceae Technical Description: Thallus gelatinous, tiny, forming minute brownish to brownish-grey cushions or tufts 0.5mm to 2 cm wide, composed of many small brown, cylindrical, knobby isidia that become very branched (coralloid), either attached directly to the substrate or attached to very small foliose lobes that are obscured by the isidia and difficult to see. Medulla of isodiametric fungal cells resembling parenchyma (requires a very thin cross-section examined under a compound scope), cells to 2:1. Photosynthetic partner (photosymbiont) the cyanobacterium Nostoc. Isidia constricted at places along their length, giving a segmented, knobby look, 0.03-0.1 mm in diameter. European specimens of L. teretiusculum have an overall gray color with some browning at the tips, with thin knobby isidia that become wider and flatter as they mature, resembling a tiny Opuntia cactus, the isidia eventually becoming small foliose lobes with new isidia attached. Some European specimens are flattened, lying parallel to the substrate Chemistry: all spot tests negative. Distinctive Characters: Tiny thalli composed of cylindrical, knobby isidia, the medulla parenchyma-like. Similar species: Leptogium cellulosum looks very similar but has cylindrical isidia with dimpled tips. Martin et al. (2002) discuss at length the morphological distinctions between L. teretiusculum and L. cellulosum. Stone and Ruchty (2006) also discuss the distinctions and show photographs. Other descriptions and illustrations: Stone & Ruchty (2006); Sierk (1964); McCune & Geiser (2009): 183; Goward et al. (1994): p. 68; Purvis et al. (1992): p.356. -

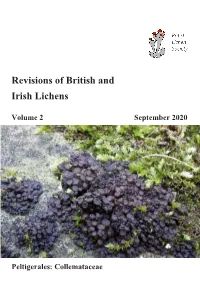

Revisions of British and Irish Lichens

Revisions of British and Irish Lichens Volume 2 September 2020 Peltigerales: Collemataceae Cover image: Scytinium turgidum, on a limestone grave monument, Abney Park cemetery, Stoke Newington, Middlesex, England. Revisions of British and Irish Lichens is a free-to-access serial publication under the auspices of the British Lichen Society, that charts changes in our understanding of the lichens and lichenicolous fungi of Great Britain and Ireland. Each volume will be devoted to a particular family (or group of families), and will include descriptions, keys, habitat and distribution data for all the species included. The maps are based on information from the BLS Lichen Database, that also includes data from the historical Mapping Scheme and the Lichen Ireland database. The choice of subject for each volume will depend on the extent of changes in classification for the families concerned, and the number of newly recognized species since previous treatments. To date, accounts of lichens from our region have been published in book form. However, the time taken to compile new printed editions of the entire lichen biota of Britain and Ireland is extensive, and many parts are out-of-date even as they are published. Issuing updates as a serial electronic publication means that important changes in understanding of our lichens can be made available with a shorter delay. The accounts may also be compiled at intervals into complete printed accounts, as new editions of the Lichens of Great Britain and Ireland. Editorial Board Dr P.F. Cannon (Department of Taxonomy & Biodiversity, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, Surrey TW9 3AB, UK). Dr A. -

MACROLICHENS of EOA GENUS SPECIES COMMON NAME Ahtiana

MACROLICHENS OF EOA GENUS SPECIES COMMON NAME Ahtiana aurescens Eastern candlewax lichen Anaptychia palmulata shaggy-fringe lichen Candelaria concolor candleflame lichen Canoparmelia caroliniana Carolina shield lichen Canoparmelia crozalsiana shield lichen Canoparmelia texana Texas shield lichen Cladonia apodocarpa stalkless cladonia Cladonia caespiticia stubby-stalked cladonia Cladonia cervicornis ladder lichen Cladonia coniocraea common powderhorn Cladonia cristatella british soldiers Cladonia cylindrica Cladonia didyma* southern soldiers Cladonia fimbriata trumpet lichen Cladonia furcata forked cladonia Cladonia incrassata powder-foot british soldiers Cladonia macilenta lipstick powderhorn Cladonia ochrochlora Cladonia parasitica fence-rail cladonia Cladonia petrophila Cladonia peziziformis turban lichen Cladonia polycarpoides peg lichen Cladonia rei wand lichen Cladonia robbinsii yellow-tongued cladonia Cladonia sobolescens peg lichen Cladonia squamosa dragon cladonia Cladonia strepsilis olive cladonia Cladonia subtenuis dixie reindeer lichen Collema coccophorum tar jelly lichen Collema crispum Collema fuscovirens Collema nigrescens blistered jelly lichen Collema polycarpon shaly jelly lichen Collema subflaccidum tree jelly lichen Collema tenax soil jelly lichen Dermatocarpon muhlenbergii leather lichen Dermatocarpon luridum xerophilum Dibaeis baeomyces pink earth lichen Flavoparmelia baltimorensis rock greenshield lichen Flavoparmelia caperata common green shield lichen Flavopunctelia soredica Powdered-edge speckled Heterodermia obscurata -

Diversity and Distribution Patterns of Endolichenic Fungi in Jeju Island, South Korea

sustainability Article Diversity and Distribution Patterns of Endolichenic Fungi in Jeju Island, South Korea Seung-Yoon Oh 1,2 , Ji Ho Yang 1, Jung-Jae Woo 1,3, Soon-Ok Oh 3 and Jae-Seoun Hur 1,* 1 Korean Lichen Research Institute, Sunchon National University, 255 Jungang-Ro, Suncheon 57922, Korea; [email protected] (S.-Y.O.); [email protected] (J.H.Y.); [email protected] (J.-J.W.) 2 Department of Biology and Chemistry, Changwon National University, 20 Changwondaehak-ro, Changwon 51140, Korea 3 Division of Forest Biodiversity, Korea National Arboretum, 415 Gwangneungsumok-ro, Pocheon 11186, Korea; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +82-61-750-3383 Received: 24 March 2020; Accepted: 1 May 2020; Published: 6 May 2020 Abstract: Lichens are symbiotic organisms containing diverse microorganisms. Endolichenic fungi (ELF) are one of the inhabitants living in lichen thalli, and have potential ecological and industrial applications due to their various secondary metabolites. As the function of endophytic fungi on the plant ecology and ecosystem sustainability, ELF may have an influence on the lichen diversity and the ecosystem, functioning similarly to the influence of endophytic fungi on plant ecology and ecosystem sustainability, which suggests the importance of understanding the diversity and community pattern of ELF. In this study, we investigated the diversity and the factors influencing the community structure of ELF in Jeju Island, South Korea by analyzing 619 fungal isolates from 79 lichen samples in Jeju Island. A total of 112 ELF species was identified and the most common species belonged to Xylariales in Sordariomycetes. -

New Species and New Records of American Lichenicolous Fungi

DHerzogiaIEDERICH 16: New(2003): species 41–90 and new records of American lichenicolous fungi 41 New species and new records of American lichenicolous fungi Paul DIEDERICH Abstract: DIEDERICH, P. 2003. New species and new records of American lichenicolous fungi. – Herzogia 16: 41–90. A total of 153 species of lichenicolous fungi are reported from America. Five species are described as new: Abrothallus pezizicola (on Cladonia peziziformis, USA), Lichenodiplis dendrographae (on Dendrographa, USA), Muellerella lecanactidis (on Lecanactis, USA), Stigmidium pseudopeltideae (on Peltigera, Europe and USA) and Tremella lethariae (on Letharia vulpina, Canada and USA). Six new combinations are proposed: Carbonea aggregantula (= Lecidea aggregantula), Lichenodiplis fallaciosa (= Laeviomyces fallaciosus), L. lecanoricola (= Laeviomyces lecanoricola), L. opegraphae (= Laeviomyces opegraphae), L. pertusariicola (= Spilomium pertusariicola, Laeviomyces pertusariicola) and Phacopsis fusca (= Phacopsis oxyspora var. fusca). The genus Laeviomyces is considered to be a synonym of Lichenodiplis, and a key to all known species of Lichenodiplis and Minutoexcipula is given. The genus Xenonectriella is regarded as monotypic, and all species except the type are provisionally kept in Pronectria. A study of the apothecial pigments does not support the distinction of Nesolechia and Phacopsis. The following 29 species are new for America: Abrothallus suecicus, Arthonia farinacea, Arthophacopsis parmeliarum, Carbonea supersparsa, Coniambigua phaeographidis, Diplolaeviopsis -

Dozens of New Lichen Species Discovered in East African Mountain Forests 22 February 2021

Dozens of new lichen species discovered in East African mountain forests 22 February 2021 Thousands of lichen specimens were collected from Kenya and Tanzania in 2009-2017, including nearly 600 Leptogium specimens. DNA analyses revealed that the dataset on Leptogium included more than 70 different species, of which no more than a dozen or so are previously known. DNA analyses were necessary, as species identification based on thallus structure is notoriously difficult in this group. "The morphological differences between species are often subtle and open to interpretation, and the outer appearances of individual species can also vary greatly depending on environmental factors. The name of the genus Leptogium alludes to a thin but Even chemical characteristics cannot be used as uniform cortex covering the outer surface of the thallus an aid for identification to the extent to which they of these lichens, in contrast to many of their relatives. are used with many other groups of lichens," When dry, the lobes of many jelly lichens are paper-thin, Rikkinen notes. often covered with skinlike wrinkles, but they swell markedly when moist.The morphological differences Due to problems in species delimitation and between Leptogium species are often subtle and open to identification, Leptogium specimens with a more or interpretation, and the outer appearances of individual species can also vary greatly depending on less similar outer appearance collected from environmental factors. Even chemical characteristics different parts of the world have traditionally been cannot be used as an aid for identification to the extent assigned to the same species. For example, to which they are used with many other groups of Leptogium cyanescens and Leptogium rivulare, lichens. -

Symbiotic Cyanobacteria in Lichens

Symbiotic Cyanobacteria in Lichens Jouko Rikkinen Faculty of Biological and Environmental Sciences, Department of Biosciences, University of Helsinki, Viikinkaari 1, 65 Helsinki, Finland Abstract Cyanolichens are obligate symbioses between fungi and cyanobacteria. They occur in many types of environments ranging from Arctic tundra and semi-deserts to tropical rainforests. Possibly even a majority of their global species diversity has not yet been described. Symbiotic cyanobacteria provide both photosynthate and fixed nitrogen to the fungal host and the relative importance of these functions differs in different cyanolichens. The cyanobiont can either be the sole photosynthetic partner or a secondary symbiont in addition to a primary green algal photobiont. In addition, the cyanolichen thallus may incorporate a plethora of other microorganisms. The fungal symbionts in cyanolichens are almost exclusively ascomycetes. Nostoc is by far the most commonly encountered cyanobacterial genus. While the cyanobacterial symbionts are presently not readily identifiable to species, molecular methods work well on the generic level and offer practical means for identifying symbiotic cyanobacterial genotypes. The present diversity of lichen cyanobionts may partly reflect the evolutionary effects of their lichen-symbiotic way of life and dispersal. 1 1. Introduction Cyanobacteria are ancient monophyletic lineage of unicellular and multicellular prokaryotes that possess chlorophyll a and are capable of oxygenic photosynthesis. Prokaryotic fossils morphologi- cally resembling modern cyanobacteria have been found from Archean deposits and it is generally believed that cyanobacterial photosynthesis raised oxygen levels in the atmosphere around 2.5–2.3 billion years ago, hence establishing the basis for the evolution of aerobic respiration. Recent findings suggest that the non-photosynthetic ancestors of cyanobacteria were anaerobic, motile and obligately fermentative (Di Rienzi et al., 2014). -

Leptogium Cyanescens Species Fact Sheet

SPECIES FACT SHEET Common Name: blue vinyl, blue jellyskin, blue oilskin Scientific Name: Leptogium cyanescens Division: Ascomycota Class: Lecanoromycetes Order: Peltigerales Family: Collemataceae Technical Description: Thallus foliose, gelatinous, 1-5 cm in diameter, with distinct upper and lower surfaces (cortices), blue-gray to occasionally turquoise in deeply shaded habitats, lacking brownish or blackish coloring, lower cortex often slightly paler than upper cortex. Photosynthetic partner (photosymbiont) the cyanobacterium Nostoc. Lobes rounded, 1-12 mm broad, margins entire to dentate to isidiate, matte, smooth to occasionally roughened but not wrinkled; lobes thin, especially near the edge of the thallus, about 50 – 70 µm near the edge and up to about 110 µm farther in. Thallus attached to substrate by scattered tufts of white hairs. Upper cortex of a single layer of cells with approximately even sides (isodiametric) 5-8 µm in diameter, up to 10 rows thick beneath apothecia. Isidia the same color as the thallus, usually abundant on the lobe surface and also developing along the lobe margins, cylindrical and often branching with age, or flattened into club-shaped lobules; marginal isidia appearing as fine teeth along the lobe edges. Isidia emerging from the thallus as small, light-colored rounded bumps becoming round-topped cylinders. Medulla made of tightly packed hyphae, giving the impression of being woven (visible only in very thin cross-sections, 1-2 cells thick, viewed at 400x). Nostoc chains are scttered throughout the medulla. Lower cortex bare except for scattered tufts of whitish hairs attaching thallus to substrate. Apothecia not common, and not seen in specimens from the Pacific Northwest; sessile to short stipitate on the upper surface of the thallus, 0.5 – 2.0 mm across, plane to convex, light brown or reddish brown; the gray margin of the apothecium entire to abundantly isidiate, light grey to cream colored. -

Flooded Jellyskin (Leptogium Rivulare)

Species at Risk Act Recovery Strategy Series Recovery Strategy for the Flooded Jellyskin Lichen (Leptogium rivulare) in Canada Flooded Jellyskin Lichen 2013 Recommended citation: Environment Canada. 2013. Recovery Strategy for the Flooded Jellyskin Lichen (Leptogium rivulare) in Canada. Species at Risk Act Recovery Strategy Series. Environment Canada, Ottawa. iv + 23 pp. For copies of the recovery strategy, or for additional information on species at risk, including COSEWIC Status Reports, residence descriptions, action plans, and other related recovery documents, please visit the Species at Risk (SAR) Public Registry (www.sararegistry.gc.ca). Cover illustration: ©Robert E. Lee Également disponible en français sous le titre « Programme de rétablissement du leptoge des terrains inondés (Leptogium rivulare) au Canada » © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, represented by the Minister of the Environment, 2013. All rights reserved. ISBN 978-1-100-21189-3 Catalogue no. En3-4/147-2013E-PDF Content (excluding the illustrations) may be used without permission, with appropriate credit to the source. Recovery Strategy for the Flooded Jellyskin Lichen 2013 PREFACE The federal, provincial, and territorial government signatories under the Accord for the Protection of Species at Risk (1996) agreed to establish complementary legislation and programs that provide for effective protection of species at risk throughout Canada. Under the Species at Risk Act (S.C. 2002, c.29) (SARA), the federal competent ministers are responsible for the preparation of recovery strategies for listed Extirpated, Endangered, and Threatened species and are required to report on progress within five years. The Minister of the Environment is the competent minister for the recovery of the Flooded Jellyskin Lichen and has prepared this strategy, as per section 37 of SARA. -

FULLTEXT01.Pdf

PhD-thesis © Lena Dahlman, 2003. Resource acquisition and allocation in Lichens Department of Ecology and Environmental Science Umeå University SE-901 87 Umeå Front cover, designed by Lena Dahlman showing a section through the tripartite lichen Lobaria pulmonaria. The dark lump is a cephalodium, containing the cyanobacte- rial photobiont and the crown-shaped structure on the right is a fungal vegetative reproductive structure called the soralium with little ball-shaped soredia on top. The green layer is the colony of the photobiont Dictyochloropsis located in the medulla. This lichen’s nitrogen acquisition is studied in paper V, and the resource allocation patterns of tripartite lichens are more thoroughly investigated in papers I, II, and III Tryckeri Print & Media, Umeå University, 309012 Papper Omslag: Silverblade Matt 300g Inlaga: Cream 90 ISBN 91-7305-496-8 2 PhD-thesis © Lena Dahlman Department of Ecology and Environmental Science Umeå University SE-901 87 Umeå ISBN 91-7305-496-8 Abstract Lichens are fascinating symbiotic systems, where a fungus and a unicellular alga, most often green (bipartite green algal lichens; 90% of all lichens), or a fi lamentous cyanobacterium (bipartite cyano- bacterial lichens; 10% of all lichens) form a new entity (a thallus) appearing as a new and integrated organism: in about 500 lichens the fungus is associated with both a cyanobacterium and an alga (tripartite lichens). In the thallus, the lichen bionts function both as individual organisms, and as a symbiont partner. Hence, in lichens, the participating partners must both be able to receive and acquire resources from the other partner(s) in a controlled way. -

Lichens in the New Red List of Estonia

Folia Cryptog. Estonica, Fasc. 44: 113–120 (2008) Lichens in the new Red List of Estonia Tiina Randlane1, Inga Jüriado1, Ave Suija2, Piret Lõhmus1 & Ede Leppik1,2 1Department of Botany, Institute of Ecology & Earth Sciences, University of Tartu, 38 Lai St., 51005 Tartu, Estonia. E-mail: [email protected] 2 Botanical and Mycological Museum, Natural History Museum of the University of Tartu, 38 Lai St., 51005 Tartu, Estonia Abstract: The compilation of the current Red List of Estonia took place during 2006–2008; the IUCN system of categories and criteria (vers. 6.1), which is accepted worldwide, was applied. Out of the 1019 lichenized, lichenicolous and closely allied fungal species recorded in Estonia in 2006, 464 species (45.5%) were evaluated while 555 species remained not estimated – in the category Not Evaluated (NE). Of the evaluated species, 213 were assigned to the so-called red-listed categories: Regionally Extinct (RE), Critically Endangered (CR), Endangered (EN), Vulnerable (VU), Near Threatened (NT) and Data Deficient (DD). 113 of them were classified as threatened (belonging to the categories CR, EN, VU). 251 species were assigned to the category Least Concerned (LC). The full enumeration of the red-listed lichens of Estonia with appropriate category and criteria is presented. Kokkuvõte: Samblikud Eesti uues punases raamatus Eesti uue punase raamatu koostamine kestis 2006–2008; kasutati IUCN’i kategooriate ja kriteeriumite laialdaselt tunnustatud süsteemi (versioon 6.1). 1019 samblikuliigist (Eesti 2006. a nimekirja järgi) hinnati 464 liigi (45,5%) ohustatuse seisundit ning 555 liiki jäid hindamata; samblikena on sealjuures tinglikult käsitletud lihheniseerunud ja lihhenikoolseid seeni ning neile süstemaatiliselt lähedasi liike.