Developing Specialist Skills in Autism Practice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Simmons (2009) Vision in Autism Spectrum Disorders.Pdf

Vision Research 49 (2009) 2705–2739 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Vision Research journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/visres Review Vision in autism spectrum disorders David R. Simmons *, Ashley E. Robertson, Lawrie S. McKay, Erin Toal, Phil McAleer, Frank E. Pollick Department of Psychology, University of Glasgow, 58 Hillhead Street, Glasgow G12 8QB, Scotland, UK article info abstract Article history: Autism spectrum disorders (ASDs) are developmental disorders which are thought primarily to affect Received 11 March 2009 social functioning. However, there is now a growing body of evidence that unusual sensory processing Received in revised form 4 August 2009 is at least a concomitant and possibly the cause of many of the behavioural signs and symptoms of ASD. A comprehensive and critical review of the phenomenological, empirical, neuroscientific and theo- retical literature pertaining to visual processing in ASD is presented, along with a brief justification of a Keywords: new theory which may help to explain some of the data, and link it with other current hypotheses about Autism the genetic and neural aetiologies of this enigmatic condition. Autism spectrum disorders Ó 2009 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. Clinical vision 1. Introduction diet or lifestyle (see Altevogt, Hanson, & Leshner, 2008; Rutter, 2009; Thornton, 2006). It is likely that both genetic and environ- Autism is a developmental disorder characterized by difficulties mental factors contribute to the aetiology of ASDs, although a with social interaction, social communication and an unusually re- number of genetic disorders can result in similar symptoms (e.g. stricted range of behaviours and interests (Frith, 2003). A diagnosis Fragile-X, Tuberous Sclerosis: see Gillberg & Coleman, 2000, for of autism also requires a clinically significant delay in language more). -

Fil-B /Advisory Committee Co

Reading Comprehension Strategies In Children With High- Functioning Autism: A Social Constructivist Perspective Item Type Thesis Authors Cotter, June Ann Download date 26/09/2021 17:04:41 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/11122/9075 READING COMPREHENSION STRATEGIES IN CHILDREN WITH HIGH FUNCTIONING AUTISM: A SOCIAL CONSTRUCTIVIST PERSPECTIVE By June Ann Cotter RECOMMENDED: £> P \ - I V v^jQ JL-V% lh -i> Advisory Committee Chair a . fil-b /Advisory Committee Co Chair, Department of Communication APPROVED: Dean, College of Liberal Arts / r Dean of the Graduate School Date READING COMPREHENSION STRATEGIES IN CHILDREN WITH HIGH- FUNCTIONING AUTISM: A SOCIAL CONSTRUCTIVIST PERSPECTIVE A DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of the University of Alaska Fairbanks in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By June Ann Cotter, MSEd. Fairbanks, Alaska May 2011 © 2011 June Ann Cotter UMI Number: 3463936 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMT Dissertation Publishing UMI 3463936 Copyright 2011 by ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This edition of the work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. uestA ® ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Abstract Individuals with autism see the world, by definition of the diagnosis, in a very different way than the typical student. -

John Hersey's Awareness of One's Environment "Characters," Carol and Willie

New 'York Times Book Re'view 4/3/94 Forward From Nowhere An autistic woman resumes her tale of trying to rna,ke sense oflife. Iiams, too, participated in con terns of behavior are not inher feelings as humans do - and nected to one another ._..- a desire iOMEBODY versations by replaying scripts ent but are learned by watching that humans have feelings in a Ms. Williams did not have Just SOMEWHERE she had heard. But, as she ex others. way that objects don't. She the opposite, she writes. "I was plains, non-autistic people use When "Somebody Somewhere" stands paralyzed before a tiny allergic to words like 'we,' 'us' or 9reaking Free From the World these bits to reflect real feelings, opens, Ms. Williams is 25 years closet because she cannot bear 'together· - words depicting )fAutlsm. genuine emotions ..... at least 'in old and liVing in London. She has what she uwould have to inflict closeness" because "closeness By Donna Williams. principle. To the autistic who is given up her characters but not upon" her clothes by squeezing made earthquakes go off inside ~38 pp. New York: unaware of real feelings (for yet learned how to function in the them in. She apologizes to them of me and compelled me to run," rimes Books/ whom, in fact, emotions feel like world without them: HWillie was as she hangs them up. Realizing pnly at the end, in a special Random House. $23. death), the memorized bits are n't there to help me understand, that objects are not aware of her friendship (which she calls a all there is. -

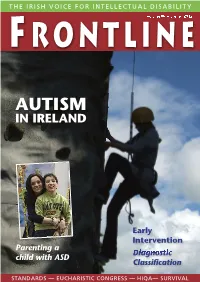

Autism in Ireland

THE IRISH VOICE FOR INTELLECTUAL DISABILITY F RONTLIVolumNe 86 • SpringE 2012 AUTISM IN IRELAND Early Intervention Parenting a Diagnostic child with ASD Classification STANDARDS — EUCHARISTIC CONGRESS — HIQA— SURVIVAL Volume 86 • Spring 2012 F RONTLINE CONTENTS FEATURE: AUTISM IN IRELAND 10 A Labyrinth? Joe McDonald attempts to answer 28 Supporting community some of the queries posed by living for adults with parents who have a child with Autism Spectrum Disorders autism . (ASD) and Developmental Disabilities (DD) 12 Applied Behaviour Analysis Nessa Hughes takes a look at (ABA) and Autism services available for adults Niall Conlon explores ABA and diagnosied with ASD. autism studies in Irish universities. 31 Our Journey 15 The future of diagnostic Maria Moran tells the story of her classification in autism daughter Jessica’s diagnosis on 04 Prof. Michael Fitzgerald comments the autism spectrum and the on the proposed new criteria for whole familys’ journey as they DSM V for autism and offers his tried to find their way through a REGULARS considered opinion of its impact on maze of treatments and opinions both parents and children. for the best method to help and care for her. 03 Editorial 16 Autism and diagnostic 04 News Update controversies Cork man’s art chosen for United Ruth Connolly explores the problem Nations stamp. of diagnostics over the wide spectrum of autism, sometimes NDA Disability shows more leading to misinformation, negative attitudes. misunderstanding and confusion. All-party agreement on disability motion on Seanad Éireann. 18 Caring for people with autism Brothers of Charity ordered to and intellectual disability pay €2 million in staff Ciaran Leonard explains why caring increments. -

Constructing Narratives and Identities in Auto/Biography About Autism

RELATIONAL REPRESENTATION: CONSTRUCTING NARRATIVES AND IDENTITIES IN AUTO/BIOGRAPHY ABOUT AUTISM by MONICA L. ORLANDO Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of English CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY May 2015 2 CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES We hereby approve the dissertation of Monica Orlando candidate for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy.* Committee Chair Kimberly Emmons Committee Member Michael Clune Committee Member William Siebenschuh Committee Member Jonathan Sadowsky Committee Member Joseph Valente Date of Defense March 3, 2015 * We also certify that written approval has been obtained for any proprietary material contained therein. 3 Dedications and Thanks To my husband Joe, for his patience and support throughout this graduate school journey. To my family, especially my father, who is not here to see me finish, but has always been so proud of me. To Kim Emmons, my dissertation advisor and mentor, who has been a true joy to work with over the past several years. I am very fortunate to have been guided through this project by such a supportive and encouraging person. To the graduate students and faculty of the English department, who have made my experience at Case both educational and enjoyable. I am grateful for having shared the past five years with all of them. 4 Table of Contents Abstract ............................................................................................................................... 5 Chapter 1: Introduction Relationality and the Construction of Identity in Autism Life Writing ........................ 6 Chapter 2 Clara Claiborne Park’s The Siege and Exiting Nirvana: Shifting Conceptions of Autism and Authority ................................................................................................. 53 Chapter 3 Transformative Narratives: Double Voicing and Personhood in Collaborative Life Writing about Autism .............................................................................................. -

Autistica Action Briefing: Adult Mental Health

Autistica Action Briefing: Adult Mental Health Harper G, Smith E, Simonoff E, Hill L, Johnson S, Davidson I. March 2019 Autistica is the UK’s autism research charity. This briefing summarises the most important scientific findings about mental health in autistic adults. It was developed in collaboration with leading researchers and autistic people with experience of the topic as an insight into the latest evidence. We strongly urge the Department of Health and Social Care, NHS policy-makers, commissioners, services and public research funders to act on this information. The evidence about mental health in autistic adults has moved on; services and policies to improve mental health must now do so as well. www.autistica.org.uk/AutismStrategy “If a neurotypical person was afraid to leave the house, that wouldn’t be seen as normal or okay. But if you’re 1 autistic you should just accept that that is the way your life is going to be.” What we know “The main problem with mental health services is that no one seems to want the responsibility 1 of putting him on their books… He keeps getting passed around departments” ▪ Almost 8 in 10 autistic adults experience a mental health problem.2 Autism is not a mental health condition itself, but mental health problems are one of the most common and serious challenges experienced by people across the spectrum. ▪ Up to 10% of adults in inpatient mental health settings are autistic,3 even though only 1% of the population is on the spectrum.4 ▪ Autistic people are often unable to access community mental health -

Educational Inclusion for Children with Autism in Palestine. What Opportunities Can Be Found to Develop Inclusive Educational Pr

EDUCATIONAL INCLUSION FOR CHILDREN WITH AUTISM IN PALESTINE. What opportunities can be found to develop inclusive educational practice and provision for children with autism in Palestine; with special reference to the developing practice in two educational settings? by ELAINE ASHBEE A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of Education University of Birmingham November 2015 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Amendments to names used in thesis The Amira Basma Centre is now known as Jerusalem Princess Basma Centre Friends Girls School is now known as Ramallah Friends Lower School ABSTRACT This study investigates inclusive educational understandings, provision and practice for children with autism in Palestine, using a qualitative, case study approach and a dimension of action research together with participants from two educational settings. In addition, data about the wider context was obtained through interviews, visits, observations and focus group discussions. Despite the extraordinarily difficult context, education was found to be highly valued and Palestinian educators, parents and decision–makers had achieved impressive progress. The research found that autism is an emerging field of interest with a widespread desire for better understanding. -

About the National Autistic Society the National Autistic Society (NAS) Is the UK’S Leading Charity for People Affected by Autism

Getting on? Growing older with autism A policy report 2 3 Contents Foreword by Baroness Greengross OBE 4 Background 5 Acknowledgements 7 Introduction 8 Chapter 1: Diagnosis 10 Under-diagnosis and referral for assessment The assessment process The impact of diagnosis Chapter 2: Research on autism in older age 14 Chapter 3: Health in older age 16 Identifying health problems Accessing healthcare Chapter 4: Preparing for the future 19 Reliance on families The support families provide Filling the gap: possible solutions Planning for transition in services Chapter 5: Ensuring appropriate services and support are available 24 Autism-friendly mainstream services Age-appropriate autism services Commissioning-appropriate services Conclusion 29 Summary of recommendations 30 Glossary and abbreviations 34 Methodology 35 Written by Anna Boehm This report would not have been possible without the generous support of The Clothworkers’ Foundation. 2 3 Foreword: Baroness Greengross I have worked in older people’s policy for over thirty years. During this time I’ve seen dramatic increases in life expectancy, debates over care funding moving to the fore of our national politics, and significant improvements in the legal protections we offer against age discrimination. During the same period, society’s understanding of autism has taken great steps forward. However, national and local policy-makers, as well as the media, very often concentrate on the effect of the disability on children. Only in the past four or five years has any real attention been paid to adults, and the needs of older adults with autism are yet to get a real look-in. So I was very pleased to chair the Autism and Ageing Commission which has worked with The National Autistic Society to develop the policy recommendations contained in this report. -

Danish and British Protection from Disability Discrimination at Work - Past, Present and Future

University of Huddersfield Repository Lane, Jackie and Videbaek Munkholm, Natalie Danish and British Protection from Disability Discrimination at Work - Past, Present and Future. Original Citation Lane, Jackie and Videbaek Munkholm, Natalie (2015) Danish and British Protection from Disability Discrimination at Work - Past, Present and Future. The International Journal of Comparative Labour law and Industrial Relations, 31 (1). pp. 91-112. ISSN 0952-617X This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/23332/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ Danish and British protection from disability discrimination at work – past, present and future Jackie Lane and Natalie Videbæk Munkholm* Disability discrimination in Denmark and Britain] Abstract: Denmark and the United Kingdom both became members of what is now the European Union in 1973 and are thus equally matched in terms of opportunity to bring their anti-discrimination laws into line with those of the EU and other supra- national bodies such as the United Nations and the Council of Europe. -

Retracing the Historical Social Care Context of Autism: a Narrative Overview

Retracing the historical social care context of autism: a narrative overview Article (Accepted Version) D'Astous, Valerie, Manthorpe, Jill, Lowton, Karen and Glaser, Karen (2016) Retracing the historical social care context of autism: a narrative overview. The British Journal of Social Work, 46 (3). pp. 789-807. ISSN 0045-3102 This version is available from Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/id/eprint/54127/ This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies and may differ from the published version or from the version of record. If you wish to cite this item you are advised to consult the publisher’s version. Please see the URL above for details on accessing the published version. Copyright and reuse: Sussex Research Online is a digital repository of the research output of the University. Copyright and all moral rights to the version of the paper presented here belong to the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. To the extent reasonable and practicable, the material made available in SRO has been checked for eligibility before being made available. Copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. http://sro.sussex.ac.uk Retracing the historical social care context of autism: A narrative overview Valerie D’Astous1*, JillManthorpe2, Karen Lowton1, and Karen Glaser1 1 Social Science, Health & Medicine, King’s College London, Strand Campus, London, WC2R 2LS, UK 2 Social Care Workforce Research Unit, King’s College London, UK *Correspondence to Valerie D’Astous, Social Science, Health & Medicine, King’s College London, Strand, London, WC2R 2LS, UK. -

Autism Spectrum Disorder Briefing Paper No 5/2013 by Lenny Roth

Autism Spectrum Disorder Briefing Paper No 5/2013 by Lenny Roth RELATED PUBLICATIONS Government policy and services to support and include people with disabilities, Briefing Paper No. 1/2007 by Lenny Roth ISSN 1325-5142 ISBN 978-0-7313-1901-5 June 2013 © 2013 Except to the extent of the uses permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this document may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means including information storage and retrieval systems, without the prior consent from the Manager, NSW Parliamentary Research Service, other than by Members of the New South Wales Parliament in the course of their official duties. Autism Spectrum Disorder by Lenny Roth NSW PARLIAMENTARY RESEARCH SERVICE Gareth Griffith (BSc (Econ) (Hons), LLB (Hons), PhD), Manager, Politics & Government/Law .......................................... (02) 9230 2356 Lenny Roth (BCom, LLB), Senior Research Officer, Law ....................................................... (02) 9230 2768 Lynsey Blayden (BA, LLB (Hons)), Research Officer, Law ................................................................. (02) 9230 3085 Talina Drabsch (BA, LLB (Hons)), Research Officer, Social Issues/Law ........................................... (02) 9230 2484 Jack Finegan (BA (Hons), MSc), Research Officer, Environment/Planning..................................... (02) 9230 2906 Daniel Montoya (BEnvSc (Hons), PhD), Research Officer, Environment/Planning ..................................... (02) 9230 2003 John Wilkinson (MA, PhD), Research Officer, Economics ...................................................... (02) 9230 2006 Should Members or their staff require further information about this publication please contact the author. Information about Research Publications can be found on the Internet at: http://www.parliament.nsw.gov.au/prod/parlment/publications.nsf/V3LIstRPSubject Advice on legislation or legal policy issues contained in this paper is provided for use in parliamentary debate and for related parliamentary purposes. -

NAS Richmond Info Pack December 2020

AUTISM: A SPECTRUM CONDITION AUTISM, ASPERGER’S SYNDROME AND SOCIAL COMMUNICATION DIFFICULTIES AN INFORMATION PACK A GUIDE TO RESOURCES, SERVICES AND SUPPORT FOR AUTISTIC PEOPLE OF ALL AGES; THEIR FAMILIES, FRIENDS, ASSOCIATES AND PROFESSIONALS Produced by the National Autistic Society’s Richmond Branch. Online edition December 2020 Introduction 1 Introduction AN INTRODUCTION: WHAT WE OFFER The Richmond Branch of The National Autistic Society is a friendly parent-led group aiming to support families and autistic people in the borough. We hold coffee mornings, liaise with other groups and provide regular updates through emails and our Branch website. We are also working with our local authority and other professionals to improve access to health, social services and educational provision. Our core objectives are: Awareness, Support, Information Our present activities: Awareness and liaison. Networking and partnering with other local organisations, sharing expertise and working with them to improve services. Raising awareness and representing families and individuals affected by autism by involvement in the local authority’s implementation of the Autism Strategy, SEND plus other autism interest/pan-disability rights groups. Family and individual support. This is offered primarily via email support, plus our coffee mornings. Information. We aim to help and inform families and autistic people, and do so via: • Our Branch website. This gives details of our Branch and NAS Head Office’s activities, other groups, general activities and events, plus the online Information Pack. • The NAS Richmond Branch Information Pack. An essential guide to autism services and support. Written by local parents, the Information Pack aims to help anyone affected by autism or Asperger syndrome, including parents, carers and anyone else who provides support.