Multiple Shocks and Downward Mobility: Learning from the Life Histories of Rural Ugandans

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Department of Fisheries Resources Annual Report 2010/2011

Department of Fisheries Resources Annual Report 2010/2011 Item Type monograph Publisher Ministry of Agriculture, Animal Industry and Fisheries Download date 02/10/2021 06:55:34 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/1834/35373 Government of Uganda MINISTRY OF AGRICULTURE ANIMAL INDUSTRY & FISHERIES DEPARTMENT OF FISHERIES RESOURCES ANNUAL REPORT 2010/2011 Final Draft i Table of Contents LIST OF TABLES AND FIGURES ............................................................................................... iv LIST OF ACRONYMS ................................................................................................................... v FOREWORD .................................................................................................................................. vi EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................. 1 1. INTRODUCTIONp .................................................................................................................. 4 1.1 Vision of DFR .................................................................................................................. 5 1.2 Mandate of DFR ............................................................................................................... 5 1.3 Functions of DFR ............................................................................................................. 5 1.4 Legal Policy and Institutional Framework ...................................................................... -

FY 2019/20 Vote:517 Kamuli District

LG Approved Workplan Vote:517 Kamuli District FY 2019/20 Foreword In accordance with Section 36 of the Local Government Act (Cap 243), Local Governments prepare appropriate plans and documents in conformity with Central Government guidelines and formats. Pursuant to the foregoing, Kamuli District Local Government has prepared the workplan for the FY2019/20. This document takes into consideration the 5 year District Development Plan for 2015/16 DQGLVWKHODVW\HDURILPSOHPHQWDWLRQRIWKHFXUUHQWSODQ7KH3ODQIRFXVHVRQWKHIROORZLQJNH\VWUDWHJLFREMHFWLYHVImprove household incomes through increased production promote and ensure the rational and sustainable utilization, development and effective management of environment and natural resources for socio-economic development. ECD programmes and LPSURYHPHQWRITXDOLW\HTXLW\UHWHQWLRQUHOHYDQFHDQGHIILFLHQF\LQEDVLFHGXFDWLRQDevelop adequate, reliable and efficient multi modal transport network in the district increasing access to safe water in rural and urban areas increasing sanitation and hygiene levels in rural and urban areas To contribute to the production of a healthy human capital through provision of equitable, safe and sustainable health services. Enhance effective participation of communities in the development process To improve service delivery across all sectors and lower level administrative units. Integration of cross cutting issues during planning, budgeting and implementation of development programs. The district has however continued to experience low/poor service delivery levels manifested by low household incomes, poor education standards, low level of immunization coverage, high maternal mortality rate, poor road network and low access to safe water among others. This district workplan focuses on a number of interventions aimed at addressing some of these challenges above through implementation of sector specific strategies highlight in the annual plans for FY 2019/20. -

Medicines Consumer Awareness Campaign Project Report

MEDICINES CONSUMER AWARENESS CAMPAIGN PROJECT REPORT 2017 This report is made possible by the support of the American People through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents of this report are the sole responsibility of Cardno Emerging Markets USA, Ltd. and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. CONSUMER AWARENESS CAMPAIGN PROJECT REPORT Authors: Coalition for Health Promotion and Social Development (HEPS Uganda) Submitted by: Cardno Emerging Markets USA, Ltd. Submitted to: USAID/Uganda Contract No.: AID-617-C-13-00005 DISCLAIMER The author’s views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. Consumer Awareness Campaign Project Report 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS ABBREVIATION........................................................................................................................................................................ 4 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT ........................................................................................................................................................ 5 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ......................................................................................................................................................... 6 1. BACKGROUND ............................................................................................................................................................. 7 1.1 Introduction -

WHO UGANDA BULLETIN February 2016 Ehealth MONTHLY BULLETIN

WHO UGANDA BULLETIN February 2016 eHEALTH MONTHLY BULLETIN Welcome to this 1st issue of the eHealth Bulletin, a production 2015 of the WHO Country Office. Disease October November December This monthly bulletin is intended to bridge the gap between the Cholera existing weekly and quarterly bulletins; focus on a one or two disease/event that featured prominently in a given month; pro- Typhoid fever mote data utilization and information sharing. Malaria This issue focuses on cholera, typhoid and malaria during the Source: Health Facility Outpatient Monthly Reports, Month of December 2015. Completeness of monthly reporting DHIS2, MoH for December 2015 was above 90% across all the four regions. Typhoid fever Distribution of Typhoid Fever During the month of December 2015, typhoid cases were reported by nearly all districts. Central region reported the highest number, with Kampala, Wakiso, Mubende and Luweero contributing to the bulk of these numbers. In the north, high numbers were reported by Gulu, Arua and Koti- do. Cholera Outbreaks of cholera were also reported by several districts, across the country. 1 Visit our website www.whouganda.org and follow us on World Health Organization, Uganda @WHOUganda WHO UGANDA eHEALTH BULLETIN February 2016 Typhoid District Cholera Kisoro District 12 Fever Kitgum District 4 169 Abim District 43 Koboko District 26 Adjumani District 5 Kole District Agago District 26 85 Kotido District 347 Alebtong District 1 Kumi District 6 502 Amolatar District 58 Kween District 45 Amudat District 11 Kyankwanzi District -

Jinja District Local Government Councils' Scorecard FY 2018/19

jinja DISTRICT LOCAL GOVERNMENT council SCORECARD assessment FY 2018/19 jinja DISTRICT LOCAL GOVERNMENT council SCORECARD assessment FY 2018/19 L-R: Ms. Rose Gamwera, Secretary General ULGA; Mr. Ben Kumumanya, PS. MoLG and Dr. Arthur Bainomugisha, Executive Director ACODE in a group photo with award winners at the launch of the 8th Local Government Councils Scorecard Report FY 2018/19 at Hotel Africana in Kampala on 10th March 2020 1.0 Introduction 1.2 The Local Government Councils Scorecard Initiative (LGCSCI) This brief was developed from the scorecard report The main building blocks in LGCSCI are the principles titled, “The Local Government Councils Scorecard and core responsibilities of Local Governments FY 2018/19. “The Next Big Steps: Consolidating as set out in Chapter 11 of the Constitution of the Gains of Decentralisation and Repositioning the Republic of Uganda, the Local Governments Act Local Government Sector in Uganda.” The brief (CAP 243) under Section 10 (c), (d) and (e). The provides key highlights of the performance of district scorecard comprises of five parameters based on elected leaders and the Council of Jinja District the core responsibilities of the local government Local Government (JDLG) during FY 2018/19. Councils, District Chairpersons, Speakers and 1.1 About the District Individual Councillors. These are classified into five categories: Financial management and oversight; Jinja District is located approximately 87 kilometres Political functions and representation; Legislation by road, east of Kampala, comprising one of the nine and related functions; Development planning and (9) districts of Busoga region with its Headquarters constituency servicing and Monitoring service located at Busoga Square within Jinja Municipality. -

Kampala, Uganda; Telephone: (256-414) 7060000 Fax: (256-414) 237553/230370; E-Mail: [email protected]; Website

2014 NPHC - Main Report National Population and Housing Census 2014 Main Report 2014 NPHC - Main Report This report presents findings from the National Population and Housing Census 2014 undertaken by the Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS). Additional information about the Census may be obtained from the Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS), Plot 9 Colville Street, P.O. box 7186 Kampala, Uganda; Telephone: (256-414) 7060000 Fax: (256-414) 237553/230370; E-mail: [email protected]; Website: www.ubos.org. Cover Photos: Uganda Bureau of Statistics Recommended Citation Uganda Bureau of Statistics 2016, The National Population and Housing Census 2014 – Main Report, Kampala, Uganda 2014 NPHC - Main Report FOREWORD Demographic and socio-economic data are The Bureau would also like to thank the useful for planning and evidence-based Media for creating awareness about the decision making in any country. Such data Census 2014 and most importantly the are collected through Population Censuses, individuals who were respondents to the Demographic and Socio-economic Surveys, Census questions. Civil Registration Systems and other The census provides several statistics Administrative sources. In Uganda, however, among them a total population count which the Population and Housing Census remains is a denominator and key indicator used for the main source of demographic data. resource allocation, measurement of the extent of service delivery, decision making Uganda has undertaken five population and budgeting among others. These Final Censuses in the post-independence period. Results contain information about the basic The most recent, the National Population characteristics of the population and the and Housing Census 2014 was undertaken dwellings they live in. -

Office of the Auditor General the Republic of Uganda

OFFICE OF THE AUDITOR GENERAL THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA REPORT OF THE AUDITOR GENERAL ON THE FINANCIAL STATEMENTS OF BUYENDE DISTRICT LOCAL GOVERNMENT FOR THE YEAR ENDED 30TH JUNE 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................ 5 2.0 AUDIT OBJECTIVES .................................................................................................................. 5 3.0 AUDIT METHODOLOGY ........................................................................................................... 6 4.0 ENTITY FINANCING ................................................................................................................. 7 5.0 FINDINGS................................................................................................................................... 7 5.1 Categorization of findings ........................................................................................................ 7 5.2 Summary of audit findings ...................................................................................................... 7 6.0 Detailed Audit Findings ............................................................................................................ 8 6.1 Unaccounted for funds ......................................................................................................... 8 6.2 Unsupported Pension payments ............................................................................................ -

Impact of Nutrition Education Centers on Food and Nutrition Security in Kamuli District, Uganda Samuel Ikendi Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Graduate Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2019 Impact of nutrition education centers on food and nutrition security in Kamuli District, Uganda Samuel Ikendi Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd Part of the Agriculture Commons Recommended Citation Ikendi, Samuel, "Impact of nutrition education centers on food and nutrition security in Kamuli District, Uganda" (2019). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 17032. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd/17032 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Impact of nutrition education centers on food and nutrition security in Kamuli District, Uganda by Samuel Ikendi A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF COMMUNITY AND REGIONAL PLANNING MASTER OF SCIENCE Co-majors: Community and Regional Planning; Sustainable Agriculture Program of Study Committee: Francis Owusu, Major Professor Carmen Bain Ann Oberhauser The student author, whose presentation of the scholarship herein was approved by the program of study committee, is solely responsible for the content of this thesis. The Graduate College will ensure this thesis is globally accessible and will not permit alterations after a degree is conferred. Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2019 Copyright © Samuel Ikendi, 2019. All rights reserved. ii DEDICATION To the NECs hosts, NEC Trainers, and my mum Christine Lubaale, may the Gracious Lord reward you all abundantly for your generosity. -

Network Analysis Kamuli District

Research Report Research Report Sustainable WASH Systems Learning Partnership NETWORK ANALYSIS OF ACTORS AFFECTING RURAL WATER SERVICE DELIVERY IN KAMULI DISTRICT, UGANDA Duncan McNicholl and Adriana Verkerk, Whave Solutions May 2018 PHOTO CREDIT: DUNCAN MCNICHOLL/WHAVE CREDIT: PHOTO Front cover: Nairuba Margrete partakes in a network mapping exercise in Ndalike Parish, Namwendwa Sub- county, Uganda. Photo Credit: Duncan McNicholl, Whave About the Sustainable WASH Systems Learning Partnership: The Sustainable WASH Systems Learning Partnership is a global United States Agency for International Development (USAID) cooperative agreement to identify locally-driven solutions to the challenge of developing robust local systems capable of sustaining water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) service delivery. This report is made possible by the generous support of the American people through USAID under the terms of the Cooperative Agreement AID-OAA-A-16-00075. The contents are the responsibility of the Sustainable WASH Systems Learning Partnership and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. For more information, visit www.globalwaters.org/SWS, or contact Elizabeth Jordan ([email protected]). 2 Table of Contents List of Figures ........................................................................................................................................................ 4 List of Tables ........................................................................................................................................................ -

Kamuli District

National Population and Housing Census 2014 Area Specific Profiles Kamuli District April 2017 National Population and Housing Census 2014 Area Specific Profiles – Kamuli District This report presents findings of National Population and Housing Census (NPHC) 2014 undertaken by the Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS). Additional information about the Census may be obtained from the UBOS Head Office, Statistics House. Plot 9 Colville Street, P. O. Box 7186, Kampala, Uganda; Telephone: +256-414 706000 Fax: +256-414 237553; E-mail: [email protected]; Website: www.ubos.org Cover Photos: Uganda Bureau of Statistics Recommended Citation Uganda Bureau of Statistics 2017, The National Population and Housing Census 2014 – Area Specific Profile Series, Kampala, Uganda. National Population and Housing Census 2014 Area Specific Profiles – Kamuli District FOREWORD Demographic and socio-economic data are useful for planning and evidence-based decision making in any country. Such data are collected through Population Censuses, Demographic and Socio-economic Surveys, Civil Registration Systems and other Administrative sources. In Uganda, however, the Population and Housing Census remains the main source of demographic data, especially at the sub-national level. Population Census taking in Uganda dates back to 1911 and since then the country has undertaken five such Censuses. The most recent, the National Population and Housing Census 2014, was undertaken under the theme ‘Counting for Planning and Improved Service Delivery’. The enumeration for the 2014 Census was conducted in August/September 2014. The Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS) worked closely with different Government Ministries, Departments and Agencies (MDAs) as well as Local Governments (LGs) to undertake the census exercise. -

Report of the Third WHO Stakeholders Meeting on Rhodesiense Human African Trypanosomiasis

Report of the third WHO stakeholders meeting on rhodesiense human African trypanosomiasis Geneva, Switzerland, 10–11 April 2019 789240 012936 Report of the third WHO stakeholders meeting on rhodesiense human African trypanosomiasis Geneva, Switzerland, 10–11 April 2019 Report of the third WHO stakeholders meeting on rhodesiense human African trypanosomiasis, Geneva, Switzerland, 10–11 April 2019 ISBN 978-92-4-001293-6 (electronic version) ISBN 978-92-4-001294-3 (print version) © World Health Organization 2020 Some rights reserved. This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- ShareAlike 3.0 IGO licence (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc- sa/3.0/igo). Under the terms of this licence, you may copy, redistribute and adapt the work for non-commercial purposes, provided the work is appropriately cited, as indicated below. In any use of this work, there should be no suggestion that WHO endorses any specific organization, products or services. The use of the WHO logo is not permitted. If you adapt the work, then you must license your work under the same or equivalent Creative Commons licence. If you create a translation of this work, you should add the following disclaimer along with the suggested citation: “This translation was not created by the World Health Organization (WHO). WHO is not responsible for the content or accuracy of this translation. The original English edition shall be the binding and authentic edition”. Any mediation relating to disputes arising under the licence shall be conducted in accordance with the mediation rules of the World Intellectual Property Organization (http://www.wipo.int/amc/en/mediation/ rules/). -

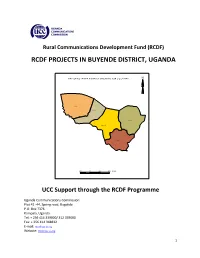

Rcdf Projects in Buyende District, Uganda

Rural Communications Development Fund (RCDF) RCDF PROJECTS IN BUYENDE DISTRICT, UGANDA MAP O F BU YEN D E D ISTR IC T SH O W IN G SU B C O UN TIES N Kid era Nko nd o Kag ul u Buye nd e Bug ay a 20 0 20 40 Km s UCC Support through the RCDF Programme Uganda Communications Commission Plot 42 -44, Spring road, Bugolobi P.O. Box 7376 Kampala, Uganda Tel: + 256 414 339000/ 312 339000 Fax: + 256 414 348832 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.ucc.co.ug 1 Table of Contents 1- Foreword……………………………………………………………….……….………..…..…....….…3 2- Background…………………………………….………………………..…………..….….……..….…4 3- Introduction………………….……………………………………..…….…………….….……….…..4 4- Project profiles……………………………………………………………………….…..…….……...5 5- Stakeholders’ responsibilities………………………………………………….….…........…12 6- Contacts………………..…………………………………………….…………………..…….……….13 List of tables and maps 1- Table showing number of RCDF projects in Buyende district………….…..……..5 2- Map of Uganda showing Buyende district………..………………….………...……….14 10- Map of Buyende district showing sub counties………..…………………………….15 11- Table showing the population of Buyende district by sub counties………...15 12- List of RCDF Projects in Buyende district…………………………………….…….……16 Abbreviations/Acronyms UCC Uganda Communications Commission RCDF Rural Communications Development Fund USF Universal Service Fund MCT Multipurpose Community Tele-centre PPDA Public Procurement and Disposal Act of 2003 POP Internet Points of Presence ICT Information and Communications Technology UA Universal Access MoES Ministry of Education and Sports MoH Ministry of Health DHO District Health Officer CAO Chief Administrative Officer RDC Resident District Commissioner 2 1. Foreword ICTs are a key factor for socio-economic development. It is therefore vital that ICTs are made accessible to all people so as to make those people have an opportunity to contribute and benefit from the socio-economic development that ICTs create.