Seeing and Hearing and Smelling Is Believing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mountain Bike

Mountain Bike Trails in West Virginia County Trail Name Land Manager Length in Miles Barbour Alum Cave Audra State Park 2.7 Dayton Park Riverfront Walk Philippi 2.5 Riverside Audra State Park 2 Berkeley Hedgesville Park Martinsburg Berkeley County Parks 0.5 and Recreation Poor House Farm Park Martinsburg Berkeley County Parks 6 and Recreation Tuscarora Creek Linear Park Martinsburg Berkeley County Parks 0.5 and Recreation Braxton Billy Linger Elk River WMA 2.2 Canoe River Elk River WMA 1.8 Cherry Tree Hunting Elk River WMA 1.7 Dynamite Elk River WMA 0.5 Gibson Elk River WMA 0.45 Hickory Flats Elk River WMA 2.4 Stony Creek Hunting Elk River WMA 2.5 Tower Falls Elk River WMA 0.4 Weston to Gauley Bridge Turnpike US Army - Corps of Engineers 10 Woodell Elk River WMA 1.1 Brooke Brooke Pioneer Rail Brooke Pioneer Rail Trail Foundation 6.7 Follansbee City Park Nature Follansbee 0.3 Panhandle Rail Weirton Parks and Recreation 4 Wellsburg Yankee Rail Wellsburg 1.1 Cabell Ritter & Boulevard Parks Greater Huntington Park & Recreation 6 District Rotary Park Greater Huntington Park & Recreation 0.5 District YMCA - Kennedy Outdoor Huntington YMCA 1 Recreation Calhoun Calhoun County Park Calhoun County Commission 3.5 Page 1 of 11 Mountain Bike Trails in West Virginia County Trail Name Land Manager Length in Miles Clay Clay County Park Clay County Parks 2 Doddridge North Bend Rail North Bend State Park Fayette Brooklyn Mine NPS - New River Gorge National River - 2 Thurmond, Minden, Cunard Church Loop NPS - New River Gorge National River - 0.1 Thurmond, -

BARBOUR Audra State Park WV Dept. of Commerce $40,798 Barbour County Park Incl

BARBOUR Audra State Park WV Dept. of Commerce $40,798 Barbour County Park incl. Playground, Court & ADA Barbour County Commission $381,302 Philippi Municipal Swimming Pool City of Philippi $160,845 Dayton Park Bathhouse & Pavilions City of Philippi $100,000 BARBOUR County Total: $682,945 BERKELEY Lambert Park Berkeley County $334,700 Berkeley Heights Park Berkeley County $110,000 Coburn Field All Weather Track Berkeley County Board of Education $63,500 Martinsburg Park City of Martinsburg $40,000 War Memorial Park Mini Golf & Concession Stand City of Martinsburg $101,500 Faulkner Park Shelters City of Martinsburg $60,000 BERKELEY County Total: $709,700 BOONE Wharton Swimming Pool Boone County $96,700 Coal Valley Park Boone County $40,500 Boone County Parks Boone County $106,200 Boone County Ballfield Lighting Boone County $20,000 Julian Waterways Park & Ampitheater Boone County $393,607 Madison Pool City of Madison $40,500 Sylvester Town Park Town of Sylvester $100,000 Whitesville Pool Complex Town of Whitesville $162,500 BOONE County Total: $960,007 BRAXTON Burnsville Community Park Town of Burnsville $25,000 BRAXTON County Total: $25,000 BROOKE Brooke Hills Park Brooke County $878,642 Brooke Hills Park Pool Complex Brooke County $100,000 Follansbee Municipal Park City of Follansbee $37,068 Follansbee Pool Complex City of Follansbee $246,330 Parkview Playground City of Follansbee $12,702 Floyd Hotel Parklet City of Follansbee $12,372 Highland Hills Park City of Follansbee $70,498 Wellsburg Swimming Pool City of Wellsburg $115,468 Wellsburg Playground City of Wellsburg $31,204 12th Street Park City of Wellsburg $5,786 3rd Street Park Playground Village of Beech Bottom $66,000 Olgebay Park - Haller Shelter Restrooms Wheeling Park Commission $46,956 BROOKE County Total: $1,623,027 CABELL Huntington Trail and Playground Greater Huntington Park & Recreation $113,000 Ritter Park incl. -

GENERAL GUIDE to the WEST VIRGINIA STATE PARKS

Campground information Special events in the Parks A full calendar of events is planned across West Virginia at state Many state parks, forests and wildlife management areas offer SiteS u e parks. From packaged theme weekends, dances and workshops, to camping opportunities. There are four general types of campsites: Campground check-out time is noon, and only one tent or trailer is ecology, history, heritage, native foods, and flora and fauna events, permitted per site. A family camping group may have only one or two you’ll find affordable fun. DeLuxe: Outdoor grill, tent pad, pull-off for trailers, picnic table, additional tents on its campsite. Camping rates are based on groups electric hookups on all sites, some with water and/or sewer hookups, of six persons or fewer, and there is a charge for each additional Wintry months include New Year’s Eve and holiday rate packages dumping station and bathhouses with hot showers, flush toilets and person above six, not exceeding 10 individuals per site. at many of the lodge parks. Ski festivals, clinics and workshops for laundry facilities. Nordic and alpine skiers are winter features at canaan valley resort All campers must vacate park campsites for a period of 48 hours after and blackwater Falls state parks. north bend’s Winter Wonder StanDarD: Same features as deluxe, with electric only available at 14 consecutive nights camping. The maximum length of stay is 14 Weekend in January includes sled rides, hikes, fireside games and some sites at some areas. Most sites do not have hookups. consecutive nights. n ature & recreation Programs indoor and outdoor sports. -

By J. Lawrence Smith Hudkins

October 2009 NON-PROFIT ORG U. S. POSTAGE Address Service Requested P A I D PERMIT NO. 1409 CHAS WV 25301 Friends of Blackwater AWP AGAIN THREATENS LOGGING IN BLACKWATER CANYON page 3 CHIEF LOGAN STATE PARK DRILLING CASE HEADED TO SUPREME COURT page 4 CANAAN VALLEY FUNDRAISER PICTORIAL page 8-9 Also Inside: Ginny Needs Your Help page 2 Congressman Rahall Blackwater Hero 2009 page 2 Second Round of Drilling Permitted on Fernow page 3 J.R. Clifford Project Welcomes Megan Lowe page 4 Cordie Hudkins Stands Up to Illegal Drilling page 5 Future Dim for Hemlock page 5 Washington: A Man of the Land page 6 NFWP Begins Work on New Thomas Trails page 7 Potomac Boat Club Fundraiser A Success! page 10 Cheerful Chickadee page 10 Dolly Sods and Uncle Sam page 11 Donor Recognition page 12 Your Comments on Blackwater Canyon page 14 In Memory and Honor page 15 Protect Chief Logan State Park page 16 Membership Form page 16 Holiday Gift Ideas page 16 Photo ©Canyon Rim Photography, Bob Jordan, see page 15 Photo ©Canyon Rim Photography, Working to protect West Virginia’s Highlands, the Blackwater River watershed and the Blackwater Canyon. 501 Elizabeth Street - Charleston, WV 25311 H 1-877-WVA-LAND H fax 304-345-3240 H www.saveblackwater.org H [email protected] October 2009 October 2009 From the Director AWP Again Threatens Logging in Blackwater Canyon On September 4, 2009 Allegheny the Forest Service gate on the Canyon Rail AWP would be violating the Endangered Board of Directors Breaking News – Ginny’s Lawyers Say Truffles Wood Products (“AWP”) notified the West Trail. -

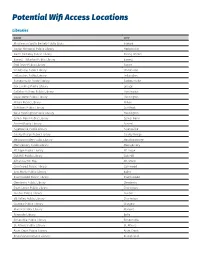

Potential Wifi Access Locations

Potential Wifi Access Locations Libraries NAME CITY Mussleman South Berkely Public Libra Inwood Naylor Memorial Public Library Hedgesville North Berkeley Public Library Falling Waters Barrett - Wharton Public Library Barrett Coal River Public Library Racine Whitesville Public Library Whitesville Follansbee Public Library Follansbee Barboursville Public Library Barboursville Cox Landing Public Library Lesage Gallaher Villiage Public Library Huntington Guyandotte Public Library Huntington Milton Public Library Milton Salt Rock Public Library Salt Rock West Huntington Public Library Huntington Center Point Public Library Center Point Ansted Public Library Ansted Fayetteville Public Library Fayetteville Gauley Bridge Public Library Gauley Bridge Meadow Bridge Public Library Meadow Bridge Montgomery Public Library Montgomery Mt Hope Public Library Mt. Hope Oak Hill Public Library Oak Hill Allegheny Mt. Top Mt. Storm Quintwood Public Library Quinwood East Hardy Public Library Baker Ravenswood Public Library Ravenswood Clendenin Public Library Clendenin Cross Lanes Public Library Charleston Dunbar Public Library Dunbar Elk Valley Public Library Charleston Glasgow Public Library Glasgow Marmet Public Library Marmet Riverside Library Belle Sissonville Public Library Sissonsville St. Albans Public Library St. Albans Alum Creek Public Library Alum Creek Branchland Outpost Library Branchland NAME CITY Fairview Public Library Fairview Mannington Public Library Mannington Benwood McMechen Public Library McMechen Cameron Public Library Cameron Sand Hill -

LAWSON HEIRS, INC., Petitioner and Intervenor Below, Appellees

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF APPEALS OF WEST VIRGINIA Case Nos. 35508 Et al. CABOT OIL & GAS CORPORATION and LAWSON HEIRS, INC., Petitioner and Intervenor Below, Appellees v. RANDY C. HUFFMAN, Cabinet Secretary, West Virginia Department of Environmental Protection, Respondent Below, Appellant, and SIERRA CLUB, INC., WEST VIRGINIA HIGHLANDS CONSERVANCY, FRIENDS OF BLACKWATER, CORDIE HUDKINS, and WEST VIRGINIA DIVISION OF NATURAL RESOURCES, Intervenors Below, Appellants. CA No. 08-C-14 Hon. Roger L.Perry Chief Judge, Seventh Judicial Circuit BRIEF OF APPELLEE, LAWSON HEIRS, INC~, IN RESPONSE TO BRIEFS BY APPELLANTS, W.VA. DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION, SIERRA CLUB, INC., W.VA. DIVISION OF NATURAL RESOURCES, CORDIE INS FRIENDS OF BLACKWATER AND· W. VA. HIGHLANDS CONSERVANCY . LARRY W. GEORGE, ESQ. (WVSB No. 1367) U Law Office of Larry W. George, PLLC ~ One Bridge Place, Suite 205 10 Hale Street . Charleston, West Virginia 25301 . RORYL,PERRYII,CLERK J(304) 556-4830 SUPREME COURT OF APPE.ALS ~ ___ OF_WEST~IR~.~!~_ COUNSEL FOR LAWSON HEIRS, INC. Intervenor Below and Appellee TABLE OF. CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION. ... .. 4 II. PROCEDURAL HISTORY .............................. 5 III. JOINDER WITH APPELLEE, CABOT OIL & GAS CORPORATION ........................... 6 IV. STATEMENT OF THE FACTS. A. History of Lawson Family Ownership ........... 6 B. "Bargain Sale" gift by the Lawson Family of the 3,271 acres of land for Chief Logan State Park................... 7 C. Reservation of the oil & gas estate from the 1960 partial gift of the lands For Chief Logan State Park............. 8 ·.D. Environmental controls on future oil & gas drilling were included in the 1960 deed for the protection of Chief Logan State Park ...................... -

Development of Outdoor Recreation Resource Amenity Indices for West Virginia

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2008 Development of outdoor recreation resource amenity indices for West Virginia Jing Wang West Virginia University Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Wang, Jing, "Development of outdoor recreation resource amenity indices for West Virginia" (2008). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 2680. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/2680 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Development of Outdoor Recreation Resource Amenity Indices for West Virginia Jing Wang Thesis submitted to the Davis College of Agriculture, Forestry, and Consumer Sciences At West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Recreation, Parks, and Tourism Resources Jinyang Deng, Ph.D., Chair Chad -

SPOKES Teachers Attend Retreat at Tygart Lake

NETWORKS 1 West Virginia’s Summer 2005 Literacy and Adult Education Newsletter Networks SPOKES teachers attend retreat at Tygart Lake By David Hollingsworth, DHHR special services coordinator On April 21 and 22, SPOKES (Strategic Planning in Occupational Knowledge for Employment and Success) ABE teachers from around the state met at Tygart Lake State Park outside of Grafton, WV to participate in the second annual retreat to discuss issues and plan for program improvement. Teachers from the 15 SPOKES classes in West Virginia spent nearly two full days and evenings sharing “best practices,” discussing curriculum materials and delivery styles, and reviewing proper programmatic procedures. They enjoyed learning and sharing experiences with a few invited guests. Beth Vass-Lutz, state adult education coordi- SPOKES teachers “enjoying” best practices. nator, and David Hollingsworth, RESA III coordinator for educational services specifically for DHHR, presided over the two-day retreat. Education and Workforce Development, pro- One guest speaker, Idress Gooden from RESA vided a workshop on the WorkKeys test and its VII, shared with the participants her views and correlation with the Key Train program, a insights on the culture of poverty, based upon computer-based curriculum designed for work- the Ruby Payne book and training series, A place academics. Framework for Understanding Poverty. The final activity was a panel from the Dr. Robin Asbury, also from RESA VII, Department of Health and Human Resources discussed the three levels of certification with (DHHR) — the “parent” agency that provides emphasis on requirements for awarding the top, the funding for the SPOKES program as well as work-readiness certificate. -

2019 ASD Summer Activities Guide

1 This list of possible summer activities for families was developed to generate some ideas for summer fun and inclusion. Activities on the list do not imply any endorsement by the West Virginia Autism Training Center. Many activities listed are low cost or no cost. Remember to check your local libraries, YMCA, and Boys and Girls Clubs; they usually have fun summer activities planned for all ages. North Bend Rail Trail goes through numerous counties and can offer hours of fun outdoor time with various activities. At the bottom of this document are county extension offices. You may contact them for information for Clover buds, 4-H, Energy Express, Youth Volunteers and other activities that they host throughout WV. Link for their website: https://extension.wvu.edu/ County List and Information in Alphabetical Order Barbour County • WV Blue and Gray Trail; First Land Battle of Civil War http://www.blueandgrayreunion.org • Phillipi Covered Bridge & Museum Route 250, Phillipi, WV • Adaland Mansion www.adaland.org • Barbour County Historical Museum Mummies https://bestthingswv.com/unusual-attractions/ Berkeley County • Circa Blue Fest, June 7-9 http://www.circabluefest.com/ • Wonderment Puppet Theater Martinsburg 412 W King St 304-260-9382 • For The Kids By Geopre Children’s Museum Martinsburg 229 E. Martin St. 304-264-9977 • Galaxy Skateland Martinsburg 1201 3rd St. 304-263-0369 2 • JayDee’s Family Fun Center (304) 229-4343 Boone County • Upper Big Branch Miners Memorial http://www.ubbminersmemorial.com/ • Waterways https://www.facebook.com/waterwayswv • Coal River Festival (304) 419-4417 • Boone County Heritage & Arts Center Madison, WV http://www.boonecountywv.org/PDF/Boone-Heritage-and-Arts-Center.pdf Braxton County • Burnsville Dam/ Recreational Area https://www.recreation.gov/camping/gateways/315 • Sutton Lake https://www.suttonlakemarina.com/about-sutton-lake • Falls Mill https://www.facebook.com/pages/category/Community/Falls-Mill-West-Virginia- 144887218858429/ • Bulltown Historic Area 304-853-2371 • Monster Museum, 208 Main St. -

Guide to Accessible Recreation in West Virginia (PDF)

West Virginia Assistive Technology System Alternate formats are available. Please call 800-841-8436 Contents INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................... 10 HOW TO USE THIS GUIDE............................................................................................................................ 10 TRAVELING IN WEST VIRGINIA .................................................................................................................... 12 Getting Around ....................................................................................................................................... 12 Trip Tips ................................................................................................................................................... 12 211 .......................................................................................................................................................... 12 Travel Information .................................................................................................................................. 12 CAMC Para-athletic Program .................................................................................................................. 13 Challenged Athletes of West Virginia ..................................................................................................... 13 West Virginia Hunter Education Association ......................................................................................... -

The Highlands Voice

West Virginia Highlands Conservancy PO. Box 306 Non-Profit Org. Charleston, WV 25321 U.S. Postage PAID Permit No. 2831 Charleston, WV The Highlands Voice Since 1967, The Monthly Publication of the West Virginia Highlands Conservancy Volume 51 No. 8 August, 2018 We Have Wilderness; Now We Need to By George E. Beetham Jr.Work to Keep It Wilderness On October 13, 1746, Thomas Lewis, a surveyor from the the time we entered the swamp I did not see a plane big Shenandoah Valley of Virginia was a member of a survey team enough for a man to lie on or horse to stand…” headed by Peter Jefferson, father of Thomas. The party’s mission Leaving the plateau, he noted in his journal, was to survey the boundaries of Lord Fairfax’s large estate. Near “Never was any poor creature in such a condition as the ridgeline of Allegheny Mountain they encountered a 16-foot high we were in, nor ever was a criminal more glad by having cliff. They managed to get to the top. What they found surprised made his escape out of prison as we were to get rid of them. It was a wide plateau, not a standard ridgeline. There were those accursed laurels.” flat rocks and a marsh. A little more than a hundred years later, not much had Farther across the plateau they encountered: changed. David Hunter Strother, who wrote under the pen name “Laurel and Ivy as thick as they can grow whose Porte Crayon (French for pencil case), wrote in 1852: branches growing of an extraordinary length are so well “In Randolph County, Virginia, is a tract of country woven together that without cutting it away it would be containing from seven to nine hundred square miles, impossible to force through them … from the beginning of entirely uninhabited, and so savage and inaccessible that it (More on p. -

Performance Review Division of Natural Resources the Park System

September 2018 PE 18-07-613 PERFORMANCE REVIEW DIVISION OF NATURAL RESOURCES THE PARK SYSTEM AUDIT OVERVIEW The West Virginia Park System Continues to Lack the Necessary Resources to Adequately Reduce the Number of Deferred Maintenance and Capital Improvement Projects. WEST VIRGINIA LEGISLATIVE AUDITOR PERFORMANCE EVALUATION & RESEARCH DIVISION JOINT COMMITTEE ON GOVERNMENT OPERATIONS Senate House of Delegates Agency/ Citizen Members Ed Gaunch, Chair Gary G. Howell, Chair Keith Rakes Mark Maynard, Vice-Chair Danny Hamrick Vacancy Ryan Weld Zack Maynard Vacancy Glenn Jeffries Richard Iaquinta Vacancy Corey Palumbo Isaac Sponaugle Vacancy JOINT COMMITTEE ON GOVERNMENT ORGANIZATION Senate House of Delegates Ed Gaunch, Chair Gary G. Howell, Chair Tony Paynter Mark Maynard, Vice-Chair Danny Hamrick, Vice-Chair Terri Funk Sypolt Greg Boso Michael T. Ferro, Minority Chair Guy Ward Charles Clements Phillip W. Diserio, Minority Vice-Chair Scott Brewer Mike Maroney Chanda Adkins Mike Caputo Randy Smith Dianna Graves Jeff Eldridge Dave Sypolt Jordan C. Hill Richard Iaquinta Tom Takubo Rolland Jennings Dana Lynch Ryan Weld Daniel Linville Justin Marcum Stephen Baldwin Sharon Malcolm Rodney Pyles Douglas E. Facemire Patrick S. Martin John Williams Glenn Jeffries Zack Maynard Corey Palumbo Pat McGeehan Mike Woelfel Jeffrey Pack WEST VIRGINIA LEGISLATIVE AUDITOR PERFORMANCE EVALUATION & RESEARCH DIVISION Building 1, Room W-314 State Capitol Complex Charleston, West Virginia 25305 (304) 347-4890 Aaron Allred John Sylvia Brandon Burton Keith Brown Noah Browning Legislative Auditor Director Research Manager Senior Research Analyst Referencer Note: On Monday, February 6, 2017, the Legislative Manager/Legislative Audi- tor’s wife, Elizabeth Summit, began employment as the Governor’s Deputy Chief Counsel.