Competitive Strategy of Private Equity: Boundary of the Investment Firm

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oil and the Financial Sector; Private Equity Perspective Gary R

Oil and the Financial Sector; Private Equity Perspective Gary R. Petersen Managing Partner & Founder, EnCap Investments November 18, 2016 Overview of EnCap Investments • Leading provider of private growth capital across upstream and midstream oil and gas • Raised aggregate capital commitments of approximately ~$27 billion across 19 institutional funds since 1988 • Exceptional track record of 2.4x ROI and 52% IRR on 174 realized investments across 19 funds • Investment strategy revolves around partnering with seasoned oil and gas executives with demonstrable track records of success Upstream - EnCap Investments Midstream - EnCap Flatrock • Core funds started in 1988 Oklahoma City • 2nd business line started in 2008 • 16 funds totaling ~$21 billion • 3 funds totaling ~$6 billion Houston Office Dallas • 21 total employees • 49 Employees San Antonio Office Houston • 19 Investment Staff San Antonio • 11 Investment Staff • 5 Technical Professionals Oklahoma City Office Dallas Office • 3 Investment Staff • 16 Employees Houston Office • 11 Investment Staff • 2 Investment Staff • 1 Technical Professional Confidential 2 Fund History • Long history of helping companies grow and create shareholder value – Provided growth capital to 242 oil and gas companies – 174 realized investments EnCap Energy EnCap Energy EnCap Energy EnCap Energy Capital Fund III Capital Fund V Capital Fund VII Capital Fund IX $405,000,000 $815,000,000 $2,500,000,000 $5,000,000,000 August 1997 July 2004 December 2007 January 2013 Reserve Acquisition Mezz. Debt Funds I- EnCap -

Draper Fisher Jurvetson

TEAM PORTFOLIO NEWS ABOUT DFJ DFJ NETWORK HOME BACK DRAPER FISHER JURVETSON, DFJ FRONTIER, AND ZONE VENTURES AWARD $250,000 TO NEUROVIGIL IN FOURTH ANNUAL DFJ VENTURE CHALLENGE Draper Fisher Jurvetson, DFJ Frontier, and Zone Ventures Award $250,000 to NeuroVigil in Fourth Annual DFJ Venture Challenge By: Press Release May. 28, 2008 UC San Diego Startup Bests 16 Teams from 12 Universities in Competition for Seed Funding MENLO PARK, Calif ‐‐ Leading early‐stage venture capital firms Draper Fisher Jurvetson (DFJ) and its network partners DFJ Frontier and Zone Ventures hosted the fourth annual DFJ Venture Challenge in Menlo Park on Wednesday. With a grand prize of $250,000 in seed stage funding, the competition is believed to be the largest winner‐take‐all business plan competition for university students. During the morning session, 16 teams from 12 universities on the West Coast presented business plans to a panel of 10 judges, comprised of venture capitalists from the DFJ Network. Six teams were selected as finalists and presented extended versions of their business plans and answered further questions from the judges in a second round of competition in the afternoon. Following the final round of judging, NeuroVigil was awarded $250,000 in seed funding. NeuroVigil is poised to revolutionize brain analysis and plans to target the sleep, transportation, and pharmaceutical industries. The company, which comprises several Nobel Laureates and leading business strategists, was founded in 2007 by Dr. Philip Low, who, as a graduate student at the Salk Institute, developed a new way to analyze brain activity using a single non‐invasive probe. -

Map of Funding Sources for EU XR Technologies

This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme under Grant Agreement N° 825545. XR4ALL (Grant Agreement 825545) “eXtended Reality for All” Coordination and Support Action D5.1: Map of funding sources for XR technologies Issued by: LucidWeb Issue date: 30/08/2019 Due date: 31/08/2019 Work Package Leader: Europe Unlimited Start date of project: 01 December 2018 Duration: 30 months Document History Version Date Changes 0.1 05/08/2019 First draft 0.2 26/08/2019 First version submitted for partners review 1.0 30/08/2019 Final version incorporating partners input Dissemination Level PU Public Restricted to other programme participants (including the EC PP Services) Restricted to a group specified by the consortium (including the EC RE Services) CO Confidential, only for members of the consortium (including the EC) This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme under Grant Agreement N° 825545. Main authors Name Organisation Leen Segers, Diana del Olmo LCWB Quality reviewers Name Organisation Youssef Sabbah, Tanja Baltus EUN Jacques Verly, Alain Gallez I3D LEGAL NOTICE The information and views set out in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official opinion of the European Union. Neither the European Union institutions and bodies nor any person acting on their behalf may be held responsible for the use which may be made of the information contained therein. © XR4ALL Consortium, 2019 Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. D5.1 Map of funding sources for XR technologies - 30/08/2019 Page 1 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................ -

A Listing of PSERS' Investment Managers, Advisors, and Partnerships

Pennsylvania Public School Employees’ Retirement System Roster of Investment Managers, Advisors, and Consultants As of March 31, 2015 List of PSERS’ Internally Managed Investment Portfolios • Bloomberg Commodity Index Overlay • Gold Fund • LIBOR-Plus Short-Term Investment Pool • MSCI All Country World Index ex. US • MSCI Emerging Markets Equity Index • Risk Parity • Premium Assistance • Private Debt Internal Program • Private Equity Internal Program • Real Estate Internal Program • S&P 400 Index • S&P 500 Index • S&P 600 Index • Short-Term Investment Pool • Treasury Inflation Protection Securities • U.S. Core Plus Fixed Income • U.S. Long Term Treasuries List of PSERS’ External Investment Managers, Advisors, and Consultants Absolute Return Managers • Aeolus Capital Management Ltd. • AllianceBernstein, LP • Apollo Aviation Holdings Limited • Black River Asset Management, LLC • BlackRock Financial Management, Inc. • Brevan Howard Asset Management, LLP • Bridgewater Associates, LP • Brigade Capital Management • Capula Investment Management, LLP • Caspian Capital, LP • Ellis Lake Capital, LLC • Nephila Capital, Ltd. • Oceanwood Capital Management, Ltd. • Pacific Investment Management Company • Perry Capital, LLC U.S. Equity Managers • AH Lisanti Capital Growth, LLC Pennsylvania Public School Employees’ Retirement System Page 1 Publicly-Traded Real Estate Securities Advisors • Security Capital Research & Management, Inc. Non-U.S. Equity Managers • Acadian Asset Management, LLC • Baillie Gifford Overseas Ltd. • BlackRock Financial Management, Inc. • Marathon Asset Management Limited • Oberweis Asset Management, Inc. • QS Batterymarch Financial Management, Inc. • Pyramis Global Advisors • Wasatch Advisors, Inc. Commodity Managers • Black River Asset Management, LLC • Credit Suisse Asset Management, LLC • Gresham Investment Management, LLC • Pacific Investment Management Company • Wellington Management Company, LLP Global Fixed Income Managers U.S. Core Plus Fixed Income Managers • BlackRock Financial Management, Inc. -

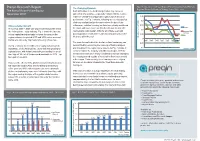

Preqin Research Report Fig

Preqin Research Report Fig. 3 Comparison of Private Equity Performance by Fund Primary The Changing Dynamic Regional Focus for Funds of Vintage Years 1995 - 2007 The Rise of Asian Private Equity Such diffi culties in the fundraising market may come as November 2010 somewhat of a surprise – especially considering the relative resilience of Asia-focused private equity funds in terms of 0.25 performance. As Fig. 3 shows, following an extended period 0.2 of strong median fund performance since the turn of the Unprecedented Growth millennium, vehicles focusing on Asia have clearly weathered 0.15 the storm with more success than their European and US Europe The period 2003 – 2008 saw unprecedented growth within 0.1 the Asian private equity industry. Fig. 1 shows the increase counterparts, with median IRRs for all vintage years still Asia and Rest of World posting positive results while funds focusing primarily on the 0.05 in total capital raised annually by funds focusing on the US region between the period 2003 and 2008, when a record West are still in the red. IRR Median Net-to-LP 0 $91bn was raised by 194 funds achieving a fi nal close. 1995 1997 1999 2001 2003 2005 2007 The main factors behind the decline in Asia fundraising can -0.05 As Fig. 2 shows, the record level of capital raised saw the be identifi ed by examining the make-up of fund managers -0.1 Vintage Year importance of the Asian private equity industry growing on and investors in the region more closely. As Fig. -

Future Finance & Investment Chapter

FUTURE FINANCE & INVESTMENT CHAPTER MEMBERS FUTURE FINANCE & INVESTMENT CHAPTER MEMBERS OF THE GRI GLOBAL COMMITTEE FUTURE FINANCE & INVESTMENT CHAIRPERSON VICE-CHAIR Audrey Klein Peter Plaut Head of Investor Relations (Funds) Executive Director Kennedy Wilson Wimmer Family Office Investor Relations (Funds) Investor - Family Office Kennedy Wilson is a global real estate operator. We focus Wimmer Family Office offers both bespoke investment portfolio on multifamily, office and industrial properties located in the solutions for family offices and high net worth individuals as Western U.S., U.K., Ireland and Spain. Headquartered in Beverly well as its core investment trend following strategy through the Wimmer Wealth Protection Fund. Hills, CA, and London, UK, Kennedy Wilson has 16 global offices. Audrey Klein is the Head of Fundraising for Kennedy Wilson Europe. Prior to Peter Plaut is an Executive Director at Wimmer Family Office focused on origination, this she held Head of Fundraising roles at several firms but is best known for researching and structuring private debt and equity transactions across a broad range starting the European business out of London for the Park Hill Real Estate of industries including specializing in real estate across the residential, office and hotel Group, a Division of Blackstone, which she ran for 9 yrs. Prior to joining Park and hospitality sectors. Minimum transaction size is $100mm to well over $1 billion. Hill, she ran her own business for 5 yrs marketing alternative asset funds Mr. Plaut is consistently recognized as a leader in the industry. Among his many across all asset classes including private equity, real estate and hedge funds achievements and awards, he was ranked as one of the Top 20 Rising Stars of Hedge to European investors comprised of pension funds, banks, family offices and Funds during the 2008 financial crisis –a recognition of his ability to manage through high net worth individuals. -

Oral History of William H. Draper III

Oral History of William H. Draper III Interviewed by: John Hollar Recorded: April 14, 2011 Mountain View, California CHM Reference number: X6084.2011 © 2011 Computer History Museum Oral History of William H. Draper III Hollar: So Bill, here I think is the challenge. There's been a great oral history done of you at Berkeley; and then you've written your book. So there's a lot of great information about you on the record. So what I thought we would try to— Draper: That's scary. I hope I say it the same way. Hollar: Well, your version of it is on the record, that's for sure. So I wanted to cover about eight areas in the hour and a half that we have. Draper: Okay. Hollar: Which is quite a bit. But I guess that's also a way of saying—we can go into as much or as little detail as you want to. But the eight areas that I was most interested in covering are your early life and your education; your early career—and with that I mean Inland Steel and meeting Pitch Johnson, and Draper, Gaither & Anderson, that section. Draper: Good. Hollar: Then Draper & Johnson—you and Pitch really getting into it together; then, of course, Sutter Hill and that very incredible fifteen-year period. Draper: Yeah, that was a good period. Hollar: A little bit of what you call "the lost decade." Draper: Okay. Hollar: Then what I call the Draper Richards Renaissance. Draper: Good. Hollar: And kind of the second chapter of venture capital for you. -

Private Equity Spotlight January 2007 / Volume 3 - Issue 1

Private Equity Spotlight January 2007 / Volume 3 - Issue 1 Welcome to the latest edition of Private Equity Spotlight, the monthly newsletter from Private Equity Intelligence, providing insights into private equity performance, investors and fundraising. Private Equity Spotlight combines information from our online products Performance Analyst, Investor Intelligence and Funds in Market. FEATURE ARTICLE page 01 INVESTOR SPOTLIGHT page 10 Overhang, what overhang? The favourable market and difficulty of getting allocations to With 2006’s $404 billion smashing all previous records for top quartile funds has led to increased LP interest in Asian private equity fund raising, some commentators are suggesting focused funds. We look at LPs investing in these funds. that there is now an ‘overhang’ of committed capital that the industry may struggle to invest. The facts suggest otherwise. • How do LPs perceive Asian focused funds? PERFORMANCE SPOTLIGHT page 05 • Who is making the most Growth in distributions to LPs and the rate of call-ups are significant investments? driving the fundraising market. Performance Spotlight looks at the trends. • Which types of investor are the most active? FUND RAISING page 06 After a record breaking year for fundraising in 2006, we • How much is being committed examine the latest news for venture and buyout funds, as well to the region? as examining the market for first-time fund vehicles. No. of Funds on INVESTOR NEWS page 12 US Europe ROW Road All the latest news on investors in private equity: Venture 202 97 83 382 • State of Wisconsin Investment Board posts high returns Buyout 100 48 36 184 boosted by its private equity portfolio Funds of Funds 65 47 12 124 • Somerset County Council Pension Fund seeks new fund of Other 129 31 42 202 funds manager • LACERA looks for new advisor Total 496 223 173 892 • Indiana PERF is set to issue real estate RFPs SUBSCRIPTIONS If you would like to receive Private Equity Spotlight each month • COPERA close to appointing new alternatives chief. -

Private Equity 05.23.12

This document is being provided for the exclusive use of SABRINA WILLMER at BLOOMBERG/ NEWSROOM: NEW YORK 05.23.12 Private Equity www.bloombergbriefs.com BRIEF NEWS, ANALYSIS AND COMMENTARY CVC Joins Firms Seeking Boom-Era Size Funds QUOTE OF THE WEEK BY SABRINA WILLMER CVC Capital Partners Ltd. hopes its next European buyout fund will nearly match its predecessor, a 10.75 billion euro ($13.6 billion) fund that closed in 2009, according to two “I think it would be helpful people familiar with the situation. That will make it one of the largest private equity funds if Putin stopped wandering currently seeking capital. One person said that CVC European Equity Partners VI LP will likely aim to raise 10 around bare-chested.” billion euros. The firm hasn’t yet sent out marketing materials. Two people said they expect it to do so — Janusz Heath, managing director of in the second half. Mary Zimmerman, an outside spokeswoman for CVC Capital, declined Capital Dynamics, speaking at the EMPEA to comment. conference on how Russia might help its reputation and attract more private equity The London-based firm would join only a few other firms that have closed or are try- investment. See page 4 ing to raise new funds of similar size to the mega funds raised during the buyout boom. Leonard Green & Partners’s sixth fund is expected to close shortly on more than $6 billion, more than the $5.3 billion its last fund closed on in 2007. Advent International MEETING TO WATCH Corp. is targeting 7 billion euros for its seventh fund, larger than its last fund, and War- burg Pincus LLC has a $12 billion target on Warburg Pincus Private Equity XI LP, the NEW JERSEY STATE INVESTMENT same goal as its predecessor. -

LAZARD GROUP LLC (Exact Name of Registrant As Specified in Its Charter)

Table of Contents UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 10-K (Mark One) ☒ ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended December 31, 2008 OR ☐ TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the transition period from to 333-126751 (Commission File Number) LAZARD GROUP LLC (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Delaware 51-0278097 (State or Other Jurisdiction of Incorporation (I.R.S. Employer Identification No.) or Organization) 30 Rockefeller Plaza New York, NY 10020 (Address of principal executive offices) Registrant’s telephone number: (212) 632-6000 Securities Registered Pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: None Securities Registered Pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None Indicate by check mark if the Registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. Yes ☒ No ☐ Indicate by check mark if the Registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or 15(d) of the Act. Yes ☐ No ☒ Indicate by check mark whether the Registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the Registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. Yes ☒ No ☐ Indicate by check mark if disclosure of delinquent filers pursuant to Item 405 of Regulation S-K is not contained herein, and will not be contained, to the best of Registrant’s knowledge, in definitive proxy or information statements incorporated by reference in Part III of this Form 10-K or any amendment to this Form 10-K. -

PEI Investor Relations, Marketing & Communications Forum 2019

June 19-20 | Convene, 730 Third Ave | New York Attendee list A.P. Moller Capital Bain Capital C-Bridge Capital Partners FTV Capital ACME Capital Banner Real Estate Group CCMP Capital Advisors Further Capital Partners Actis Barings Centerbridge Partners GCM Grosvenor Advent International Basis Investment Group Cerberus Capital Management General Atlantic AE Industrial Partners Battery Ventures Charlesbank Capital Partners General Catalyst Partners AEA Investors BBH Capital Partners The Chauncey F. Lufkin III Gennx360 AEW Capital Management BC Partners Foundation Genstar Capital AIMA The Beach Company The City of New York, Finance Global Infrastructure Partners Alcentra Berkshire Partners Civitas Capital Grain Management Alcion Ventures Bernhard Capital Partners Coller Capital Gryphon Investors Allianz Capital Partners Bicknell Family Holding Cornell Capital GTCR Altor Equity Partners Company Court Square Capital Partners Halstatt American Securities Bison Crescent Capital Group Hamilton Lane AMP Capital BKM Capital Partners CRV Hammes Angelo Gordon Blackstone Cypress Real Estate Advisors Hammond, Kennedy, Whitney Antares Capital Blue Heron Asset Managment Denham Capital & Co Apollo Global Management Blue Water Energy Duff & Phelps Hancock Capital Management ARC Financial Corp Bridge Investment Group Dyal Capital Partners Harvard Management Company ArcLight Capital Partners BroadVail Capital Edelman HCI Equity Partners Argosy Capital Brook Venture Partners EnCap Investments HGGC Arroyo Energy Investment Brookfield Asset Management EQT Partners -

Proptech 3.0: the Future of Real Estate

University of Oxford Research PropTech 3.0: the future of real estate PROPTECH 3.0: THE FUTURE OF REAL ESTATE WWW.SBS.OXFORD.EDU PROPTECH 3.0: THE FUTURE OF REAL ESTATE PropTech 3.0: the future of real estate Right now, thousands of extremely clever people backed by billions of dollars of often expert investment are working very hard to change the way real estate is traded, used and operated. It would be surprising, to say the least, if this burst of activity – let’s call it PropTech 2.0 - does not lead to some significant change. No doubt many PropTech firms will fail and a lot of money will be lost, but there will be some very successful survivors who will in time have a radical impact on what has been a slow-moving, conservative industry. How, and where, will this happen? Underlying this huge capitalist and social endeavour is a clash of generations. Many of the startups are driven by, and aimed at, millennials, but they often look to babyboomers for money - and sometimes for advice. PropTech 2.0 is also engineering a much-needed boost to property market diversity. Unlike many traditional real estate businesses, PropTech is attracting a diversified pool of talent that has a strong female component, representation from different regions of the world and entrepreneurs from a highly diverse career and education background. Given the difference in background between the establishment and the drivers of the PropTech wave, it is not surprising that there is some disagreement about the level of disruption that PropTech 2.0 will create.