There Has Been Much Media Interest in the New Code

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Let's Join the Circus

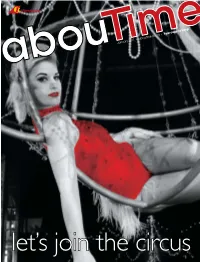

January 2011 • aboutime.co.za • Your copy to keep let’s join the circus NTS E CONT contents On the Cover An evening spent at Madame Zingara’s Theatre of Dreams is an enchanted encounter, where fairies hand out heart shaped cookies, cowboys and princesses serve food dripping in chocolate, and beautiful women swing effortlessly from the chandeliers. It is an intoxicating experience played out in a giant, tented palace of mirrors and lights. But does the magic continue through the looking glass? Is circus life just as enchanting on the other side of the tent? Cover pic © Madame Zingara 26 Oh, to be in the Circus! 61 Facing the Future 32 Singing in the New Year Photo Essay 66 The Square Kilometre Array Features 46 Big Top Baroque Cirque du Soleil 87 What Women Want 52 The Zip Zap Circus School 107 Golfing with Gary 41 Cruising the Oceans Blue 65 Hot Time in the City 64 on Gordon The New Kings Hotel Travel 50 57 Smulkos vir die Langpad 72 Weddings by Design 70 Recipes from Bosman’s Wine & Dine Wine 8 www.aboutime.co.za 26 Oh, to be in the Circus! 61 Facing the Future 32 Singing in the New Year Photo Essay 66 The Square Kilometre Array 46 Big Top Baroque Cirque du Soleil 87 What Women Want 52 The Zip Zap Circus School 107 Golfing with Gary 41 Cruising the Oceans Blue 65 Hot Time in the City 64 on Gordon 50 The New Kings Hotel 57 Smulkos vir die Langpad 72 Weddings by Design 70 Recipes from Bosman’s NTS E CONT contents 74 The Power of One The Sick Leaves 82 Cape Town’s Favourite Day Out The J&B Met 79 Riding the Rails Baglett Entertainment 88 -

Incubator Building Alconbury Weald Cambridgeshire Post-Excavation

Incubator Building Alconbury Weald Cambridgeshire Post-Excavation Assessment for Buro Four on behalf of Urban & Civic CA Project: 669006 CA Report: 13385 CHER Number: 3861 June 2013 Incubator Building Alconbury Weald Cambridgeshire Post-Excavation Assessment CA Project: 669006 CA Report: 13385 CHER Number: 3861 Authors: Jeremy Mordue, Supervisor Jonathan Hart, Publications Officer Approved: Martin Watts, Head of Publications Signed: ……………………………………………………………. Issue: 01 Date: 25 June 2013 This report is confidential to the client. Cotswold Archaeology accepts no responsibility or liability to any third party to whom this report, or any part of it, is made known. Any such party relies upon this report entirely at their own risk. No part of this report may be reproduced by any means without permission. © Cotswold Archaeology Unit 4, Cromwell Business Centre, Howard Way, Newport Pagnell, Milton Keynes, MK16 9QS t. 01908 218320 e. [email protected] 1 Incubator Building, Alconbury Weald, Cambridgeshire: Post-Excavation Assessment © Cotswold Archaeology CONTENTS SUMMARY ..................................................................................................................... 4 1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................ 5 2 AIMS AND OBJECTIVES ................................................................................... 6 3 METHODOLOGY ............................................................................................... 6 4 RESULTS ......................................................................................................... -

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist Ein Karaokesystem der Firma Showtronic Solutions AG in Zusammenarbeit mit Karafun. Karaoke-Katalog Update vom: 13/10/2020 Singen Sie online auf www.karafun.de Gesamter Katalog TOP 50 Shallow - A Star is Born Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Skandal im Sperrbezirk - Spider Murphy Gang Griechischer Wein - Udo Jürgens Verdammt, Ich Lieb' Dich - Matthias Reim Dancing Queen - ABBA Dance Monkey - Tones and I Breaking Free - High School Musical In The Ghetto - Elvis Presley Angels - Robbie Williams Hulapalu - Andreas Gabalier Someone Like You - Adele 99 Luftballons - Nena Tage wie diese - Die Toten Hosen Ring of Fire - Johnny Cash Lemon Tree - Fool's Garden Ohne Dich (schlaf' ich heut' nacht nicht ein) - You Are the Reason - Calum Scott Perfect - Ed Sheeran Münchener Freiheit Stand by Me - Ben E. King Im Wagen Vor Mir - Henry Valentino And Uschi Let It Go - Idina Menzel Can You Feel The Love Tonight - The Lion King Atemlos durch die Nacht - Helene Fischer Roller - Apache 207 Someone You Loved - Lewis Capaldi I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Über Sieben Brücken Musst Du Gehn - Peter Maffay Summer Of '69 - Bryan Adams Cordula grün - Die Draufgänger Tequila - The Champs ...Baby One More Time - Britney Spears All of Me - John Legend Barbie Girl - Aqua Chasing Cars - Snow Patrol My Way - Frank Sinatra Hallelujah - Alexandra Burke Aber Bitte Mit Sahne - Udo Jürgens Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Wannabe - Spice Girls Schrei nach Liebe - Die Ärzte Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Country Roads - Hermes House Band Westerland - Die Ärzte Warum hast du nicht nein gesagt - Roland Kaiser Ich war noch niemals in New York - Ich War Noch Marmor, Stein Und Eisen Bricht - Drafi Deutscher Zombie - The Cranberries Niemals In New York Ich wollte nie erwachsen sein (Nessajas Lied) - Don't Stop Believing - Journey EXPLICIT Kann Texte enthalten, die nicht für Kinder und Jugendliche geeignet sind. -

8123 Songs, 21 Days, 63.83 GB

Page 1 of 247 Music 8123 songs, 21 days, 63.83 GB Name Artist The A Team Ed Sheeran A-List (Radio Edit) XMIXR Sisqo feat. Waka Flocka Flame A.D.I.D.A.S. (Clean Edit) Killer Mike ft Big Boi Aaroma (Bonus Version) Pru About A Girl The Academy Is... About The Money (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug About The Money (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug, Lil Wayne & Jeezy About Us [Pop Edit] Brooke Hogan ft. Paul Wall Absolute Zero (Radio Edit) XMIXR Stone Sour Absolutely (Story Of A Girl) Ninedays Absolution Calling (Radio Edit) XMIXR Incubus Acapella Karmin Acapella Kelis Acapella (Radio Edit) XMIXR Karmin Accidentally in Love Counting Crows According To You (Top 40 Edit) Orianthi Act Right (Promo Only Clean Edit) Yo Gotti Feat. Young Jeezy & YG Act Right (Radio Edit) XMIXR Yo Gotti ft Jeezy & YG Actin Crazy (Radio Edit) XMIXR Action Bronson Actin' Up (Clean) Wale & Meek Mill f./French Montana Actin' Up (Radio Edit) XMIXR Wale & Meek Mill ft French Montana Action Man Hafdís Huld Addicted Ace Young Addicted Enrique Iglsias Addicted Saving abel Addicted Simple Plan Addicted To Bass Puretone Addicted To Pain (Radio Edit) XMIXR Alter Bridge Addicted To You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Avicii Addiction Ryan Leslie Feat. Cassie & Fabolous Music Page 2 of 247 Name Artist Addresses (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. Adore You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miley Cyrus Adorn Miguel Adorn Miguel Adorn (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel Adorn (Remix) Miguel f./Wiz Khalifa Adorn (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel ft Wiz Khalifa Adrenaline (Radio Edit) XMIXR Shinedown Adrienne Calling, The Adult Swim (Radio Edit) XMIXR DJ Spinking feat. -

The Transport System of Medieval England and Wales

THE TRANSPORT SYSTEM OF MEDIEVAL ENGLAND AND WALES - A GEOGRAPHICAL SYNTHESIS by James Frederick Edwards M.Sc., Dip.Eng.,C.Eng.,M.I.Mech.E., LRCATS A Thesis presented for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Salford Department of Geography 1987 1. CONTENTS Page, List of Tables iv List of Figures A Note on References Acknowledgements ix Abstract xi PART ONE INTRODUCTION 1 Chapter One: Setting Out 2 Chapter Two: Previous Research 11 PART TWO THE MEDIEVAL ROAD NETWORK 28 Introduction 29 Chapter Three: Cartographic Evidence 31 Chapter Four: The Evidence of Royal Itineraries 47 Chapter Five: Premonstratensian Itineraries from 62 Titchfield Abbey Chapter Six: The Significance of the Titchfield 74 Abbey Itineraries Chapter Seven: Some Further Evidence 89 Chapter Eight: The Basic Medieval Road Network 99 Conclusions 11? Page PART THREE THr NAVIGABLE MEDIEVAL WATERWAYS 115 Introduction 116 Chapter Hine: The Rivers of Horth-Fastern England 122 Chapter Ten: The Rivers of Yorkshire 142 Chapter Eleven: The Trent and the other Rivers of 180 Central Eastern England Chapter Twelve: The Rivers of the Fens 212 Chapter Thirteen: The Rivers of the Coast of East Anglia 238 Chapter Fourteen: The River Thames and Its Tributaries 265 Chapter Fifteen: The Rivers of the South Coast of England 298 Chapter Sixteen: The Rivers of South-Western England 315 Chapter Seventeen: The River Severn and Its Tributaries 330 Chapter Eighteen: The Rivers of Wales 348 Chapter Nineteen: The Rivers of North-Western England 362 Chapter Twenty: The Navigable Rivers of -

BB-1971-12-25-II-Tal

0000000000000000000000000000 000000.00W M0( 4'' .................111111111111 .............1111111111 0 0 o 041111%.* I I www.americanradiohistory.com TOP Cartridge TV ifape FCC Extends Radiation Cartridges Limits Discussion Time (Based on Best Selling LP's) By MILDRED HALL Eke Last Week Week Title, Artist, Label (Dgllcater) (a-Tr. B Cassette Nos.) WASHINGTON-More requests for extension of because some of the home video tuners will utilize time to comment on the government's rulemaking on unused TV channels, and CATV people fear conflict 1 1 THERE'S A RIOT GOIN' ON cartridge tv radiation limits may bring another two- with their own increasing channel capacities, from 12 Sly & the Family Stone, Epic (EA 30986; ET 30986) month delay in comment deadline. Also, the Federal to 20 and more. 2 2 LED ZEPPELIN Communications Commission is considering a spin- Cable TV says the situation is "further complicated Atlantic (Ampex M87208; MS57208) off of the radiated -signal CTV devices for separate by the fact that there is a direct connection to the 3 8 MUSIC consideration. subscriber's TV set from the cable system to other Carole King, Ode (MM) (8T 77013; CS 77013) In response to a request by Dell-Star Corp., which subscribers." Any interference factor would be mul- 4 4 TEASER & THE FIRECAT roposes a "wireless" or "radiated signal" type system, tiplied over a whole network of CATV homes wired Cat Stevens, ABM (8T 4313; CS 4313) the FCC granted an extension to Dec. 17 for com- to a master antenna. was 5 5 AT CARNEGIE HALL ments, and to Dec. -

River Nene Waterspace Study

River Nene Waterspace Study Northampton to Peterborough RICHARD GLEN RGA ASSOCIATES November 2016 ‘All rights reserved. Copyright Richard Glen Associates 2016’ Richard Glen Associates have prepared this report in accordance with the instructions of their clients, Environment Agency & the Nenescape Landscape Partnership, for their sole DQGVSHFL¿FXVH$Q\RWKHUSHUVRQVZKRXVHDQ\LQIRUPDWLRQFRQWDLQHGKHUHLQGRVRDW their own risk. River Nene Waterspace Study River Nene Waterspace Study Northampton to Peterborough On behalf of November 2016 Prepared by RICHARD GLEN RGA ASSOCIATES River Nene Waterspace Study Contents 1.0 Introduction 3.0 Strategic Context 1.1 Partners to the Study 1 3.1 Local Planning 7 3.7 Vision for Biodiversity in the Nene Valley, The Wildlife Trusts 2006 11 1.2 Aims of the Waterspace Study 1 3.1.1 North Northamptonshire Joint Core Strategy 2011-2031 7 3.8 River Nene Integrated Catchment 1.3 Key Objectives of the Study 1 3.1.2 West Northamptonshire Management Plan. June 2014 12 1.4 Study Area 1 Joint Core Strategy 8 3.9 The Nene Valley Strategic Plan. 1.5 Methodology 2 3.1.3 Peterborough City Council Local Plan River Nene Regional Park, 2010 13 1.6 Background Research & Site Survey 2 Preliminary Draft January 2016 9 3.10 Destination Nene Valley Strategy, 2013 14 1.7 Consultation with River Users, 3.2 Peterborough Long Term Transport 3.11 A Better Place for All: River Nene Waterway Providers & Local Communities 2 Strategy 2011 - 2026 & Plan, Environment Agency 2006 14 Local Transport Plan 2016 - 2021 9 1.8 Report 2 3.12 Peterborough -

Lo(:Zpo MEGAUPLOAD LIMITED, VESTOR LIMITED, DEMANDED KIM DOTCOM, MATHIAS ORTMANN, and BRAM VANDERKOLK

FILED IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT. FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF VIRGINIA Alexandria Division -r, l ~~ ' r rz I 0 r_:, U: 0 I L·.· '"' (\l 1' r . WARNER MUSIC GROUP CORP., UMG RECORDINGS, INC., SONY MUSIC ENTERTAINMENT, and CAPITOL RECORDS, LLC, Plaintiffs, Civil Action No. I:1 t/ cAl 5 7Lf v. JURY TRIAL Lo(:zpo MEGAUPLOAD LIMITED, VESTOR LIMITED, DEMANDED KIM DOTCOM, MATHIAS ORTMANN, and BRAM VANDERKOLK, Defendants. COMPLAINT Plaintiffs Warner Music Group Corp., UMG Recordings, Inc., Sony Music Entertainment, and Capitol Records, LLC, by their attorneys, hereby allege as follows: NATURE OF THE ACTION 1. This is an action for copyright infringement under the copyright laws of the United States, Title 17, United States Code. 2. Plaintiffs are record companies that, along with their affiliated companies, produce, manufacture, distribute, sell, and license the vast majority of legitimate commercial sound recordings in this country. Defendants are a group of entities and individuals that operated a notorious Internet copyright infringement website and service, known as "Megaupload," up until the time of their January 2012 indictment on federal criminal copyright infringement charges. The United States Department of Justice's criminal case against Defendants is currently pending in this District. Defendants' business, which included operating the Megaupload website formerly located at www.Megaupload.com, has been devoted to the Internet piracy of the most popular copyrighted entertainment content in the United States and around the world, including Plaintiffs’ sound recordings to which Plaintiffs and/or their affiliated and/or predecessor companies own exclusive rights under copyright and, on information and belief, Plaintiffs’ sound recordings protected under the laws of various states. -

AUDIO + VIDEO 10/11/11 Audio & Video Releases *Click on the Artist Names to Be Taken Directly to the Sell Sheet

NEW RELEASES WEA.COM ISSUE 21 OCTOBER 11 + OCTOBER 18, 2011 LABELS / PARTNERS Atlantic Records Asylum Bad Boy Records Bigger Picture Curb Records Elektra Fueled By Ramen Nonesuch Rhino Records Roadrunner Records Time Life Top Sail Warner Bros. Records Warner Music Latina Word AUDIO + VIDEO 10/11/11 Audio & Video Releases *Click on the Artist Names to be taken directly to the Sell Sheet. Click on the Artist Name in the Order Due Date Sell Sheet to be taken back to the Recap Page Street Date CD- NON 528728 BJORK Biophilia $18.98 10/11/11 9/21/11 Biophilia (2LP 180 Gram NON A-528477 BJORK Vinyl)(w/Download) $28.98 10/11/11 9/21/11 GDP A-2668 GRATEFUL DEAD Europe '72 (3LP) $59.98 10/11/11 9/21/11 CD- ATL 528533 HAMILTON PARK TBD $5.94 10/11/11 9/21/11 CD- ATN 528890 HAYES, HUNTER Hunter Hayes $18.98 10/11/11 9/21/11 CD- PARLOR MOB, RRR 177982 THE Dogs $13.99 10/11/11 9/21/11 A- PARLOR MOB, RRR 177981 THE Dogs (2LP) $15.98 10/11/11 9/21/11 10/11/11 Late Additions Street Date Order Due Date CD- SIR 528841 READY SET, THE Feel Good Now $7.98 10/11/11 9/21/11 Last Update: 08/17/11 ARTIST: Bjork TITLE: Biophilia Label: NON/Nonesuch Config & Selection #: CD 528728 Street Date: 10/11/11 Order Due Date: 09/21/11 UPC: 075597964080 Compact Disc Box Count: 30 Unit Per Set: 1 SRP: $18.98 Alphabetize Under: B OTHER EDITIONS: For the latest up to date info on A:075597964349 Biophilia (2LP 180 Gram this release visit WEA.com. -

Pressetext PDF (0.1

FLO RIDA US Multi -Platinum Rapper endlich wieder in Deutschland unterwegs Aktuelle ›My House‹ EP von 2015 noch immer in den deutschen Top 50! Keine Party ohne Flo Rida: Ob ›Low‹ (7-fach Platin), ›Right Round‹, die schnellstverkaufende Digitale Single ever (eine Million bezahlte Downloads in zwei Wochen und inzwischen 15-fach Platin prämiert)), der David Guetta produzierten Hymne ›Club Can´t Handle Me‹ (3-fach Platin), ›Wild Ones (feat.Sia)‹ (9-fach Platin), ›Whistle‹ (9-fach Platin), ›Sweet Spot‹ mit Vocals von Jennifer Lopez oder ›Good Feeling‹ (10-fach Platin) - was er auch anfasst, wird zum weltweiten Mega-Seller. Geboren und aufgewachsen in Carol City, der rauheren Ecke von Miami, war Musik schon früh ein großer Stabilisator im Leben von Tramar Dillard aka Flo Rida. Dass daraus allerdings mal eine derart globale Mega-Erfolgsstory werden würde, konnte man damals indes nicht ahnen. Nach ersten Gehversuchen als Rapper im Teenageralter landete Flo Rida für einige Zeit in Los Angeles unter den Fittichen von DeVante Swing, einem ehemaligen Mitglied der R&B Band Jodeci. Nach mehreren vergeblichen Versuchen, dort einen Plattendeal zu ergattern, kehrte er 2006 nach Miami zurück, kam bei Poe Boy Entertainment unter und unterzeichnete kurz darauf bei Atlantic Records. Dies war der Auftakt für einen Höhenflug, wie er auch heutzutage äußerst selten geworden ist: Sein Debutalbum ›Mail On Sunday‹ von 2008 enthielt drei Singles, eine davon ›Low‹. Der Song hielt sich sage und schreibe zehn Wochen lang auf Platz eins der Billboard Hot 100, erhielt den People´s Choice Award als ›Favourite HipHop Song‹ und heimste zwei Grammy Nominierungen für ›Best Rap/Sung Collaboration‹ als auch ›Best Rap Song‹ ein. -

Iron Production in Leicestershire, Rutland and Northamptonshire in Antiquity by Frances Condron

Iron Production in Leicestershire, Rutland and Northamptonshire in Antiquity by Frances Condron Iron production in Leicestershire, Rutland and Northamptonshire during the Roman period is well attested, though to date the region has not been considered one of importance. This paper outlines the range of settlements involved in smelting and smithing, and suggests models for the organisation of production and development through time. It is suggested that surplus iron was being made and transported outside the region, possibly to the northern garrisons, following the archaeologically documented movement of lower Nene Valley wares. A gazetteer of smelting and smithing sites is provided. Iron production in Leicestershire, Rutland and Northamptonshire during the Roman period is well attested, though to date the region has not been considered one of importance. Two iron-working regions of note have been revealed, on the Weald of Kent (Cleere 1974; Cleere & Crossley 1985), and in the Forest of Dean (Fulford & Allen 1992). In the East Midlands, the range of settlements involved and duration of production indicate a long and complex history of iron working, in some cases showing continuity from late Iron Age practices. However, there were clearly developments both in the nature and scale of production, at the top end of the scale indicative of planned operations. This paper explores the organisation of this production within sites and across the region, and outlines possible trade networks. The transition from Iron Age to Roman saw the introduction of new iron working technology (the shaft furnace in particular), and of equal significance, a shift in the organisation of production. -

A Beautifully Presented Grade Ii Listed Property, Forming the Largest Portion of a Stone Water Mill of 1770, Which Was Converte

A BEAUTIFULLY PRESENTED GRADE II LISTED PROPERTY, FORMING THE LARGEST PORTION OF A STONE WATER MILL OF 1770, WHICH WAS CONVERTED IN 1991 INTO FOUR PROPERTIES, SITUATED IN AN ATTRACTIVE SETTING ON THE BANKS OF THE RIVER NENE the mill, mill lane, water newton, peterborough, cambridgeshire, pe8 6ly A BEAUTIFULLY PRESENTED GRADE II LISTED PROPERTY, FORMING THE LARGEST PORTION OF A STONE WATER MILL OF 1770, WHICH WAS CONVERTED IN 1991 INTO FOUR PROPERTIES, SITUATED IN AN ATTRACTIVE SETTING ON THE BANKS OF THE RIVER NENE the mill, mill lane, water newton, peterborough, cambridgeshire, pe8 6ly Dining kitchen w Sitting room w Principal bedroom w Guest ensuite bedroom w Two further bedrooms w Family bathroom w Driveway & parking w Garage w Landscaped private garden w Riverside setting Mileage Peterborough 7.5 miles (Trains to Cambridge & London Kings Cross from 51 minutes) w Oundle 10 miles w Stamford 14 miles w Huntingdon 18 miles Situation The attractive Conservation Village of Water Newton has a collection of largely stone houses and lies close to the River Nene to the west of Peterborough. The village is bypassed by the A1 and is approximately 2 miles north of Alwalton village, which has a pub, post office and village shop. A footbridge over the River Nene, close to The Mill, and public footpath provides an attractive rural walk through fields to the villages of Ailsworth and Castor with their public house restaurants, village shop and facilities. The Georgian market towns of Oundle and Stamford, and the Cathedral City of Peterborough, provide a good range of shopping, services and leisure facilities.