Vertebrate Biostratigraphy of the Eocene Galisteo Formation, North-Central New Mexico Spencer G

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Perissodactyla: Tapirus) Hints at Subtle Variations in Locomotor Ecology

JOURNAL OF MORPHOLOGY 277:1469–1485 (2016) A Three-Dimensional Morphometric Analysis of Upper Forelimb Morphology in the Enigmatic Tapir (Perissodactyla: Tapirus) Hints at Subtle Variations in Locomotor Ecology Jamie A. MacLaren1* and Sandra Nauwelaerts1,2 1Department of Biology, Universiteit Antwerpen, Building D, Campus Drie Eiken, Universiteitsplein, Wilrijk, Antwerp 2610, Belgium 2Centre for Research and Conservation, Koninklijke Maatschappij Voor Dierkunde (KMDA), Koningin Astridplein 26, Antwerp 2018, Belgium ABSTRACT Forelimb morphology is an indicator for order Perissodactyla (odd-toed ungulates). Modern terrestrial locomotor ecology. The limb morphology of the tapirs are widely accepted to belong to a single enigmatic tapir (Perissodactyla: Tapirus) has often been genus (Tapirus), containing four extant species compared to that of basal perissodactyls, despite the lack (Hulbert, 1973; Ruiz-Garcıa et al., 1985) and sev- of quantitative studies comparing forelimb variation in eral regional subspecies (Padilla and Dowler, 1965; modern tapirs. Here, we present a quantitative assess- ment of tapir upper forelimb osteology using three- Wilson and Reeder, 2005): the Baird’s tapir (T. dimensional geometric morphometrics to test whether bairdii), lowland tapir (T. terrestris), mountain the four modern tapir species are monomorphic in their tapir (T. pinchaque), and the Malayan tapir (T. forelimb skeleton. The shape of the upper forelimb bones indicus). Extant tapirs primarily inhabit tropical across four species (T. indicus; T. bairdii; T. terrestris; T. rainforest, with some populations also occupying pinchaque) was investigated. Bones were laser scanned wet grassland and chaparral biomes (Padilla and to capture surface morphology and 3D landmark analysis Dowler, 1965; Padilla et al., 1996). was used to quantify shape. -

Origin and Beyond

EVOLUTION ORIGIN ANDBEYOND Gould, who alerted him to the fact the Galapagos finches ORIGIN AND BEYOND were distinct but closely related species. Darwin investigated ALFRED RUSSEL WALLACE (1823–1913) the breeding and artificial selection of domesticated animals, and learned about species, time, and the fossil record from despite the inspiration and wealth of data he had gathered during his years aboard the Alfred Russel Wallace was a school teacher and naturalist who gave up teaching the anatomist Richard Owen, who had worked on many of to earn his living as a professional collector of exotic plants and animals from beagle, darwin took many years to formulate his theory and ready it for publication – Darwin’s vertebrate specimens and, in 1842, had “invented” the tropics. He collected extensively in South America, and from 1854 in the so long, in fact, that he was almost beaten to publication. nevertheless, when it dinosaurs as a separate category of reptiles. islands of the Malay archipelago. From these experiences, Wallace realized By 1842, Darwin’s evolutionary ideas were sufficiently emerged, darwin’s work had a profound effect. that species exist in variant advanced for him to produce a 35-page sketch and, by forms and that changes in 1844, a 250-page synthesis, a copy of which he sent in 1847 the environment could lead During a long life, Charles After his five-year round the world voyage, Darwin arrived Darwin saw himself largely as a geologist, and published to the botanist, Joseph Dalton Hooker. This trusted friend to the loss of any ill-adapted Darwin wrote numerous back at the family home in Shrewsbury on 5 October 1836. -

Mammal and Plant Localities of the Fort Union, Willwood, and Iktman Formations, Southern Bighorn Basin* Wyoming

Distribution and Stratigraphip Correlation of Upper:UB_ • Ju Paleocene and Lower Eocene Fossil Mammal and Plant Localities of the Fort Union, Willwood, and Iktman Formations, Southern Bighorn Basin* Wyoming U,S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESS IONAL PAPER 1540 Cover. A member of the American Museum of Natural History 1896 expedition enter ing the badlands of the Willwood Formation on Dorsey Creek, Wyoming, near what is now U.S. Geological Survey fossil vertebrate locality D1691 (Wardel Reservoir quadran gle). View to the southwest. Photograph by Walter Granger, courtesy of the Department of Library Services, American Museum of Natural History, New York, negative no. 35957. DISTRIBUTION AND STRATIGRAPHIC CORRELATION OF UPPER PALEOCENE AND LOWER EOCENE FOSSIL MAMMAL AND PLANT LOCALITIES OF THE FORT UNION, WILLWOOD, AND TATMAN FORMATIONS, SOUTHERN BIGHORN BASIN, WYOMING Upper part of the Will wood Formation on East Ridge, Middle Fork of Fifteenmile Creek, southern Bighorn Basin, Wyoming. The Kirwin intrusive complex of the Absaroka Range is in the background. View to the west. Distribution and Stratigraphic Correlation of Upper Paleocene and Lower Eocene Fossil Mammal and Plant Localities of the Fort Union, Willwood, and Tatman Formations, Southern Bighorn Basin, Wyoming By Thomas M. Down, Kenneth D. Rose, Elwyn L. Simons, and Scott L. Wing U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 1540 UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1994 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR BRUCE BABBITT, Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Robert M. Hirsch, Acting Director For sale by U.S. Geological Survey, Map Distribution Box 25286, MS 306, Federal Center Denver, CO 80225 Any use of trade, product, or firm names in this publication is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. -

Attachment J Assessment of Existing Paleontologic Data Along with Field Survey Results for the Jonah Field

Attachment J Assessment of Existing Paleontologic Data Along with Field Survey Results for the Jonah Field June 12, 2007 ABSTRACT This is compilation of a technical analysis of existing paleontological data and a limited, selective paleontological field survey of the geologic bedrock formations that will be impacted on Federal lands by construction associated with energy development in the Jonah Field, Sublette County, Wyoming. The field survey was done on approximately 20% of the field, primarily where good bedrock was exposed or where there were existing, debris piles from recent construction. Some potentially rich areas were inaccessible due to biological restrictions. Heavily vegetated areas were not examined. All locality data are compiled in the separate confidential appendix D. Uinta Paleontological Associates Inc. was contracted to do this work through EnCana Oil & Gas Inc. In addition BP and Ultra Resources are partners in this project as they also have holdings in the Jonah Field. For this project, we reviewed a variety of geologic maps for the area (approximately 47 sections); none of maps have a scale better than 1:100,000. The Wyoming 1:500,000 geology map (Love and Christiansen, 1985) reveals two Eocene geologic formations with four members mapped within or near the Jonah Field (Wasatch – Alkali Creek and Main Body; Green River – Laney and Wilkins Peak members). In addition, Winterfeld’s 1997 paleontology report for the proposed Jonah Field II Project was reviewed carefully. After considerable review of the literature and museum data, it became obvious that the portion of the mapped Alkali Creek Member in the Jonah Field is probably misinterpreted. -

Guidebook Contains Preliminary Findings of a Number of Concurrent Projects Being Worked on by the Trip Leaders

TH FRIENDS OF THE PLEISTOCENE, ROCKY MOUNTAIN-CELL, 45 FIELD CONFERENCE PLIO-PLEISTOCENE STRATIGRAPHY AND GEOMORPHOLOGY OF THE CENTRAL PART OF THE ALBUQUERQUE BASIN OCTOBER 12-14, 2001 SEAN D. CONNELL New Mexico Bureau of Geology and Mineral Resources-Albuquerque Office, New Mexico Institute of Mining and Technology, 2808 Central Ave. SE, Albuquerque, New Mexico 87106 DAVID W. LOVE New Mexico Bureau of Geology and Mineral Resources, New Mexico Institute of Mining and Technology, 801 Leroy Place, Socorro, NM 87801 JOHN D. SORRELL Tribal Hydrologist, Pueblo of Isleta, P.O. Box 1270, Isleta, NM 87022 J. BRUCE J. HARRISON Dept. of Earth and Environmental Sciences, New Mexico Institute of Mining and Technology 801 Leroy Place, Socorro, NM 87801 Open-File Report 454C and D Initial Release: October 11, 2001 New Mexico Bureau of Geology and Mineral Resources New Mexico Institute of Mining and Technology 801 Leroy Place, Socorro, NM 87801 NMBGMR OFR454 C & D INTRODUCTION This field-guide accompanies the 45th annual Rocky Mountain Cell of the Friends of the Pleistocene (FOP), held at Isleta Lakes, New Mexico. The Friends of the Pleistocene is an informal gathering of Quaternary geologists, geomorphologists, and pedologists who meet annually in the field. The field guide has been separated into two parts. Part C (open-file report 454C) contains the three-days of road logs and stop descriptions. Part D (open-file report 454D) contains a collection of mini-papers relevant to field-trip stops. This field guide is a companion to open-file report 454A and 454B, which accompanied a field trip for the annual meeting of the Rocky Mountain/South Central Section of the Geological Society of America, held in Albuquerque in late April. -

Perissodactyla, Mammalia) from the Middle Eocene of Myanmar Un Nouveau Tapiromorphe Basal (Perissodactyla, Mammalia) De L’Eocène Moyen Du Myanmar

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by RERO DOC Digital Library Geobios 39 (2006) 513–519 http://france.elsevier.com/direct/GEOBIO/ Original article A new basal tapiromorph (Perissodactyla, Mammalia) from the middle Eocene of Myanmar Un nouveau tapiromorphe basal (Perissodactyla, Mammalia) de l’Eocène moyen du Myanmar Grégoire Métais a, Aung Naing Soe b, Stéphane Ducrocq c,* a Carnegie Museum of Natural History, Section of Vertebrate Paleontology, 4400 Forbes Avenue, Pittsburgh, PA 15213, USA b Department of Geology, Yangon University, Yangon 11422, Myanmar c Laboratoire de Géobiologie, Biochronologie et Paléontologie Humaine, UMR 6046 CNRS, Faculté des Sciences de Poitiers, 40, avenue du recteur-Pineau, 86022 Poitiers cedex, France Received 29 September 2004; accepted 10 May 2005 Available online 20 March 2006 Abstract A new genus and species of tapiromorph, Skopaiolophus burmese nov. gen., nov. sp., is described from the middle Eocene Pondaung For- mation in central Myanmar. This small form displays a striking selenolophodont morphology associated with a mixture of primitive “condylar- thran” dental characters and derived tapiromorph features. Skopaiolophus is here tentatively referred to a group of Asian tapiromorphs unknown so far. The occurrence of such a form in Pondaung suggests that primitive tapiromorphs might have persisted in southeast Asia until the late middle Eocene while they became extinct elsewhere in both Eurasia and North America. © 2006 Elsevier SAS. All rights reserved. Résumé Un nouveau genre et une nouvelle espèce de tapiromorphe, Skopaiolophus burmese nov. gen. nov. sp., sont décrits dans la Formation de Pondaung d’âge fini-éocène moyen, au Myanmar. -

Sexual Dimorphism in Perissodactyl Rhinocerotid Chilotherium Wimani from the Late Miocene of the Linxia Basin (Gansu, China)

Sexual dimorphism in perissodactyl rhinocerotid Chilotherium wimani from the late Miocene of the Linxia Basin (Gansu, China) SHAOKUN CHEN, TAO DENG, SUKUAN HOU, QINQIN SHI, and LIBO PANG Chen, S., Deng, T., Hou, S., Shi, Q., and Pang, L. 2010. Sexual dimorphism in perissodactyl rhinocerotid Chilotherium wimani from the late Miocene of the Linxia Basin (Gansu, China). Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 55 (4): 587–597. Sexual dimorphism is reviewed and described in adult skulls of Chilotherium wimani from the Linxia Basin. Via the anal− ysis and comparison, several very significant sexually dimorphic features are recognized. Tusks (i2), symphysis and oc− cipital surface are larger in males. Sexual dimorphism in the mandible is significant. The anterior mandibular morphology is more sexually dimorphic than the posterior part. The most clearly dimorphic character is i2 length, and this is consistent with intrasexual competition where males invest large amounts of energy jousting with each other. The molar length, the height and the area of the occipital surface are correlated with body mass, and body mass sexual dimorphism is compared. Society behavior and paleoecology of C. wimani are different from most extinct or extant rhinos. M/F ratio indicates that the mortality of young males is higher than females. According to the suite of dimorphic features of the skull of C. wimani, the tentative sex discriminant functions are set up in order to identify the gender of the skulls. Key words: Mammalia, Perissodactyla, Chilotherium wimani, sexual dimorphism, statistics, late Miocene, China. Shaokun Chen [[email protected]], Chongqing Three Gorges Institute of Paleoanthropology, China Three Gorges Museum, 236 Ren−Min Road, Chongqing 400015, China and Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, 142 Xi−Zhi−Men−Wai Street, P.O. -

Preliminary Geologic Map of the Albuquerque 30' X 60' Quadrangle

Preliminary Geologic Map of the Albuquerque 30’ x 60’ Quadrangle, north-central New Mexico By Paul L. Williams and James C. Cole Open-File Report 2005–1418 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior Gale A. Norton, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey P. Patrick Leahy, Acting Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia 2006 For product and ordering information: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS Suggested citation: Williams, Paul L., and Cole, James C., 2006, Preliminary Geologic Map of the Albuquerque 30’ x 60’ quadrangle, north-central New Mexico: U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 2005-1418, 64 p., 1 sheet scale 1:100,000. Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this report is in the public domain, permission must be secured from the individual copyright owners to reproduce any copyrighted material contained within this report. ii Contents Abstract.................................................................................................................1 Introduction ...........................................................................................................2 Geography and geomorphology.........................................................................3 -

Rapid and Early Post-Flood Mammalian Diversification Videncede in the Green River Formation

The Proceedings of the International Conference on Creationism Volume 6 Print Reference: Pages 449-457 Article 36 2008 Rapid and Early Post-Flood Mammalian Diversification videncedE in the Green River Formation John H. Whitmore Cedarville University Kurt P. Wise Southern Baptist Theological Seminary Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/icc_proceedings DigitalCommons@Cedarville provides a publication platform for fully open access journals, which means that all articles are available on the Internet to all users immediately upon publication. However, the opinions and sentiments expressed by the authors of articles published in our journals do not necessarily indicate the endorsement or reflect the views of DigitalCommons@Cedarville, the Centennial Library, or Cedarville University and its employees. The authors are solely responsible for the content of their work. Please address questions to [email protected]. Browse the contents of this volume of The Proceedings of the International Conference on Creationism. Recommended Citation Whitmore, John H. and Wise, Kurt P. (2008) "Rapid and Early Post-Flood Mammalian Diversification Evidenced in the Green River Formation," The Proceedings of the International Conference on Creationism: Vol. 6 , Article 36. Available at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/icc_proceedings/vol6/iss1/36 In A. A. Snelling (Ed.) (2008). Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference on Creationism (pp. 449–457). Pittsburgh, PA: Creation Science Fellowship and Dallas, TX: Institute for Creation Research. Rapid and Early Post-Flood Mammalian Diversification Evidenced in the Green River Formation John H. Whitmore, Ph.D., Cedarville University, 251 N. Main Street, Cedarville, OH 45314 Kurt P. Wise, Ph.D., Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, 2825 Lexington Road. -

Early Eocene Fossils Suggest That the Mammalian Order Perissodactyla Originated in India

ARTICLE Received 7 Jul 2014 | Accepted 15 Oct 2014 | Published 20 Nov 2014 DOI: 10.1038/ncomms6570 Early Eocene fossils suggest that the mammalian order Perissodactyla originated in India Kenneth D. Rose1, Luke T. Holbrook2, Rajendra S. Rana3, Kishor Kumar4, Katrina E. Jones1, Heather E. Ahrens1, Pieter Missiaen5, Ashok Sahni6 & Thierry Smith7 Cambaytheres (Cambaytherium, Nakusia and Kalitherium) are recently discovered early Eocene placental mammals from the Indo–Pakistan region. They have been assigned to either Perissodactyla (the clade including horses, tapirs and rhinos, which is a member of the superorder Laurasiatheria) or Anthracobunidae, an obscure family that has been variously considered artiodactyls or perissodactyls, but most recently placed at the base of Proboscidea or of Tethytheria (Proboscidea þ Sirenia, superorder Afrotheria). Here we report new dental, cranial and postcranial fossils of Cambaytherium, from the Cambay Shale Formation, Gujarat, India (B54.5 Myr). These fossils demonstrate that cambaytheres occupy a pivotal position as the sister taxon of Perissodactyla, thereby providing insight on the phylogenetic and biogeographic origin of Perissodactyla. The presence of the sister group of perissodactyls in western India near or before the time of collision suggests that Perissodactyla may have originated on the Indian Plate during its final drift toward Asia. 1 Center for Functional Anatomy & Evolution, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, 1830 E. Monument Street, Baltimore, Maryland 21205, USA. 2 Department of Biological Sciences, Rowan University, Glassboro, New Jersey 08028, USA. 3 Department of Geology, H.N.B. Garhwal University, Srinagar 246175, Uttarakhand, India. 4 Wadia Institute of Himalayan Geology, Dehradun 248001, Uttarakhand, India. 5 Research Unit Palaeontology, Ghent University, Krijgslaan 281-S8, B-9000 Ghent, Belgium. -

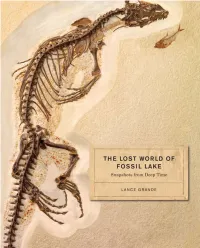

The Lost World of Fossil Lake

Snapshots from Deep Time THE LOST WORLD of FOSSIL LAKE lance grande With photography by Lance Grande and John Weinstein The University of Chicago Press | Chicago and London Ray-Finned Fishes ( Superclass Actinopterygii) The vast majority of fossils that have been mined from the FBM over the last century and a half have been fossil ray-finned fishes, or actinopterygians. Literally millions of complete fossil ray-finned fish skeletons have been excavated from the FBM, the majority of which have been recovered in the last 30 years because of a post- 1970s boom in the number of commercial fossil operations. Almost all vertebrate fossils in the FBM are actinopterygian fishes, with perhaps 1 out of 2,500 being a stingray and 1 out of every 5,000 to 10,000 being a tetrapod. Some actinopterygian groups are still poorly understood be- cause of their great diversity. One such group is the spiny-rayed suborder Percoidei with over 3,200 living species (including perch, bass, sunfishes, and thousands of other species with pointed spines in their fins). Until the living percoid species are better known, ac- curate classification of the FBM percoids (†Mioplosus, †Priscacara, †Hypsiprisca, and undescribed percoid genera) will be unsatisfac- tory. 107 Length measurements given here for actinopterygians were made from the tip of the snout to the very end of the tail fin (= total length). The FBM actinop- terygian fishes presented below are as follows: Paddlefishes (Order Acipenseriformes, Family Polyodontidae) Paddlefishes are relatively rare in the FBM, represented by the species †Cros- sopholis magnicaudatus (fig. 48). †Crossopholis has a very long snout region, or “paddle.” Living paddlefishes are sometimes called “spoonbills,” “spoonies,” or even “spoonbill catfish.” The last of those common names is misleading because paddlefishes are not closely related to catfishes and are instead close relatives of sturgeons. -

Paleoenvironmental Implications of Small-Animal Fossils from the Black Mountain Turtle Layer and Associated Layers, Eocene of Wyoming

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Master's Theses Graduate Research 2020 Paleoenvironmental Implications of Small-Animal Fossils from the Black Mountain Turtle Layer and Associated Layers, Eocene of Wyoming Jeremy McLarty [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/theses Part of the Biology Commons Recommended Citation McLarty, Jeremy, "Paleoenvironmental Implications of Small-Animal Fossils from the Black Mountain Turtle Layer and Associated Layers, Eocene of Wyoming" (2020). Master's Theses. 145. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/theses/145 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Research at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT PALEOENVIRONMENTAL IMPLICATIONS OF SMALL-ANIMAL FOSSILS FROM THE BLACK MOUNTIAN TURTLE LAYER AND ASSOCIATED LAYERS, EOCENE OF WYOMING By JEREMY MCLARTY Chair: H. Thomas Goodwin, Ph.D. ABSTRACT OF GRADUATE STUDENT RESEARCH Thesis Andrews University College of Arts and Sciences Title: PALEOENVIRONMENTAL IMPLICATIONS OF SMALL-ANIMAL FOSSILS FROM THE BLACK MOUNTAIN TURTLE LAYER AND ASSOCIATED LAYERS, EOCENE OF WYOMING Name of researcher: Jeremy A. McLarty Name and degree of faculty chair: H. Thomas Goodwin, Ph.D. Date completed: March 2020 The Bridger Formation is an Early Middle Eocene deposit in southwestern Wyoming that preserves a rich record of life from North America. Some horizons within the Bridger Formation contain abundant fossil turtle shells, but turtle skulls are rarely found. Previous research focused on one of these fossil-rich horizons, the Black Mountain turtle layer, to develop a model for the abundance and taphonomic condition of the fossil turtles.