Water Management Systems in Colonial South Australia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

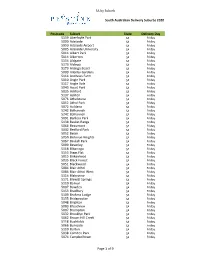

Public Road Register As at 29 May 2017

Adelaide Hills Council - Public Road Register as at 29 May 2017 NAME FROM TO SUBURB Hierachy CLASS SURFACE SEGMENTNO LENGTH (in Meters) ACKLAND AVENUE Glenside Road White Avenue CRAFERS Local LOCL SEALED 10 260.29 ACKLAND AVENUE White Avenue End of Road CRAFERS Local LOCL SEALED 20 173.8 ADELAIDE GULLY ROAD Millbrook Road Mount Gawler Road INGLEWOOD Medium Use LOCL UNSEALED 10 1092.03 ADELAIDE GULLY ROAD Mount Gawler Road Bagshaw Road INGLEWOOD Medium Use LOCL UNSEALED 20 1660.08 ADELAIDE GULLY ROAD Bagshaw Road South Para Road KERSBROOK Medium Use LOCL UNSEALED 30 1095.46 AGNES STREET Forreston Road Jamieson Street FORRESTON Local LOCL SEALED 10 119.25 AIRSTRIP ROAD Lower Hermitage Road Rural Property Address 122 LOWER HERMITAGE Low Use LOCL UNSEALED 10 1219.97 AIRSTRIP ROAD Rural Property Address 122 Rural Property Address 230 LOWER HERMITAGE Low Use LOCL UNSEALED 20 1073.47 AIRSTRIP ROAD Rural Property Address 230 Mount Gawler Road LOWER HERMITAGE Low Use LOCL UNSEALED 30 871.42 ALAN STREET Randell Terrace Cul de sac GUMERACHA Minor Collector LOCL SEALED 10 280.1 ALAN STREET Cul-de-sac North End GUMERACHA Local LOCL SEALED 20 24.69 ALBERT AVENUE Sheoak Road George Avenue CRAFERS WEST Local LOCL SEALED 10 220.35 ALDERLEY ROAD Edgeware Road Arundel Road ALDGATE Local LOCL SEALED 10 251.38 ALDERLEY ROAD Arundel Road Suffolk Road ALDGATE Local LOCL SEALED 20 218.38 ALDGATE TERRACE Strathalbyn Road End of Seal BRIDGEWATER Local LOCL SEALED 10 347.73 ALDGATE VALLEY ROAD Stock Road Mi Mi Road MYLOR Minor Collector COLL SEALED 10 768.49 ALDGATE -

Photography by John Hodgson Foreword By

Editor in chief Christopher B. Daniels Foreword by Photography by John Hodgson Barbara Hardy Table of contents Foreword by Barbara Hardy 13 Preface and acknowledgements 14 CHAPTER 1 Introduction 35 Box 1: The watercycle Philip Roetman 38 Box 2: The four colours of freshwater Jennifer McKay 44 Box 3: Environmentally sustainable development (ESD) Jennifer McKay 46 Box 4: Sustainable development timeline Jennifer McKay 47 Box 5: Adelaide’s water supply timeline Thorsten Mosisch 48 CHAPTER 2 The variable climate 51 Elizabeth Curran, Christopher Wright, Darren Ray Box 6: Does Adelaide have a Mediterranean climate? Elizabeth Curran and Darren Ray 53 Box 7: The nature of flooding Robert Bourman 56 Box 8: Floods in the Adelaide region Chris Wright 61 Box 9: Significant droughts Elizabeth Curran 65 CHAPTER 3 Catchments and waterways 69 Robert P. Bourman, Nicholas Harvey, Simon Bryars Box 10: The biodiversity of Buckland Park Kate Smith 71 Box 11: Tulya Wodli Riparian Restoration Project Jock Conlon 77 Box 12: Challenges to environmental flows Peter Schultz 80 Box 13: The flood of 1931 David Jones 83 Box 14: Why conserve the Field River? Chris Daniels 87 CHAPTER 4 Aquifers and groundwater 91 Steve Barnett, Edward W. Banks, Andrew J. Love, Craig T. Simmons, Nabil Z. Gerges Box 15: Soil profiles and soil types in the Adelaide region Don Cameron 93 Box 16: Why do Adelaide houses crack in summer? Don Cameron 95 Box 17: Salt damp John Goldfinch 99 Box 18: Saltwater intrusion Ian Clark 101 CHAPTER 5 Biodiversity of the waterways 105 Christopher B. Daniels, -

The River Torrens—Friend and Foe Part 2

The River Torrens—friend and foe Part 2: The river as an obstacle to be crossed RICHARD VENUS Richard Venus BTech, BA, GradCertArchaeol, MIE Aust is a retired electrical engineer who now pursues his interest in forensic heritology, researching and writing about South Australia’s engineering heritage. He is Chairman of Engineering Heritage South Australia and Vice President of the History Council of South Australia. His email is [email protected] Beginnings In Part 1 we looked the River Torrens as a friend—a source of water vital to the establishment of the new settlement. However, in common with so many other European settlements, the developing community very quickly polluted its own water supply and another source had to be found. This was still the River Torrens but the water was collected in the Torrens Gorge, about 13 kilometres north-east of the City, and piped down Payneham Road to the Valve House in the East Parklands. Water from this source was first made available in December 1860 as reported in the South Australian Advertiser on 26 December. The significant challenge presented by the Torrens was getting across it. In summer, when the river was little more than a series of pools, you could just walk across. However, there must have been a significant body of water somewhere – probably in the vicinity of today’s weir – because in July 1838 tenders were called ‘For the rent for six months of the small punt on the Torrens for foot passengers, for each of whom a toll of one penny will be authorised to be charged from day-light to dark, and two pence after dark’ (Register 28 July). -

Forestrysa Cudlee Creek Forest Trails Fire Recovery Strategy

ForestrySA Cudlee Creek Forest Trails Fire Recovery Strategy November 2020 Adelaide Mountain Bike Club Gravity Enduro South Australia Human Projectiles Mountain Bike Club Inside Line Downhill Mountain Bike Club Acknowledgements ForestrySA would like to take the opportunity to acknowledge the achievement of those involved in the long history of the Cudlee Creek Trails including a number of ForestrySA managers, coordinators and rangers, staff from other Government agencies such as Primary Industries SA, Office for Recreation, Sport and Racing, Department for Environment and Water and the Adelaide Hills Council. Bike SA has played a key role in the development of this location since the early 2000s and input provided from the current and former Chief Executives is acknowledged. Nick Bowman has provided a significant input to the development of this location as a mountain bike destination. Volunteer support and coordination provided by Brad Slade from the Human Projectiles MTB Club, other club members and the Foxy Creakers have also been a significant help. ForestrySA also acknowledges the support from Inside Line MTB Club, the Adelaide Mountain Bike Club and more recently the Gravity Enduro MTB Club and all other volunteers and anyone who has assisted with trail development, auditing , maintenance and event management over many years. This report was prepared by TRC Tourism for ForestrySA in relation to the development of the Cudlee Creek Forest Trails Fire Recovery Strategy Disclaimer Any representation, statement, opinion or advice, expressed or implied in this document is made in good faith but on the basis that TRC Tourism Pty. Ltd., directors, employees and associated entities are not liable for any damage or loss whatsoever which has occurred or may occur in relation to taking or not taking action in respect of any representation, statement or advice referred to in this document. -

Glenthorne State Heritage Area

GLENTHORNE STATE HERITAGE AREA Proposal to the Hon. David Speirs MLC, Minister for Environment and Water and Recommendations for a Heritage Precinct at Glenthorne by Dr Pamela Smith (Senior Research Fellow, College of Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences, Flinders University) for the Friends of Glenthorne Revised September 2018 (March 2018) Table of Contents 1 Introduction ........................................................................................................... 1 2 State Heritage Legislation ....................................................................................... 5 3 Review of the current status of State heritage registered buildings.......................... 5 4 Glenthorne. Proposed State Heritage Area and ‘Heritage Precinct’ ........................ 15 Attachments Attachment 1. Heritage Statement for Glenthorne. Attachment 2. South Australian Heritage Places Act 1993 Part 7: Attachment 3. University of Adelaide, 2004, Heritage Listed Buildings Inventory, p. 79,81- 88, 90 – Glenthorne. Report to the University of Adelaide by McDougall & Vines, 2004. ii 1 Introduction The Friends of Glenthorne believe that the historic property Glenthorne, O’Halloran Hill, fulfils the criteria for registration as a State Heritage Area on the South Australian Register of Heritage Places. Glenthorne is currently an agricultural property of 208ha at O’Halloran Hill, S.A.; it was transferred in June 2018 from the University of Adelaide to the South Australian government for inclusion in the Glenthorne National Park. First -

OPEN SPACE and PLACES for PEOPLE GRANT PROGRAM 2019/20 - Metropolitan Councils

OPEN SPACE AND PLACES FOR PEOPLE GRANT PROGRAM 2019/20 - Metropolitan Councils OPEN SPACE AND PLACES FOR PEOPLE GRANT PROGRAM 2019/20 - Metropolitan Councils PROJECT NAME Whitmore Square/ Iparrityi Master Plan - Stage 1 Upgrade (City of Adelaide) COST AND FUNDING CONTRIBUTION Council contribution $1,400,000 Planning and Development Fund contribution $900,000 TOTAL PROJECT COST $2,300,000 PROJECT DESCRIPTION Council is seeking funding to deliver the first stage of the master plan to establish pleasant walking paths and extend the valued leafy character of the square from its centre to its edges. This project involves: Safety improvements to the northern tri-intersection at Morphett and Wright Streets. Greening and paths that frame the inner edges of the square. The Northern tri-intersection will commence first, followed by the greening and pedestrian connections. TIMELINE OF THE WORKS Construction work to begin May and be completed by December 2020. Masterplan perspective PROJECT NAME Moonta Street Upgrade (City of Adelaide) COST AND FUNDING CONTRIBUTION Contribution Source Amount Council contribution TBC Planning and Development Fund contribution $2,000,000 TOTAL PROJECT COST $4,000,000* PROJECT DESCRIPTION Council is seeking funding to establish Moonta Street as the next key linkage in connecting the Central Market to Riverbank Precinct through north-south road laneways. The project involves: • the installation of quality stone paving throughout and the installation of landscaping to position Moonta Street as a comfortable green promenade and a premium precinct for evening activity. TIMELINE OF WORKS • The first stage of this project is detailed design prior to any works on ground commencing. -

Summary of Groundwater Recharge Estimates for the Catchments of the Western Mount Lofty Ranges Prescribed Water Resources Area

TECHNICAL NOTE 2008/16 Department of Water, Land and Biodiversity Conservation SUMMARY OF GROUNDWATER RECHARGE ESTIMATES FOR THE CATCHMENTS OF THE WESTERN MOUNT LOFTY RANGES PRESCRIBED WATER RESOURCES AREA Graham Green and Dragana Zulfic November 2007 © Government of South Australia, through the Department of Water, Land and Biodiversity Conservation 2008 This work is Copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968 (Cwlth), no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission obtained from the Department of Water, Land and Biodiversity Conservation. Requests and enquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be directed to the Chief Executive, Department of Water, Land and Biodiversity Conservation, GPO Box 2834, Adelaide SA 5001. Disclaimer The Department of Water, Land and Biodiversity Conservation and its employees do not warrant or make any representation regarding the use, or results of the use, of the information contained herein as regards to its correctness, accuracy, reliability, currency or otherwise. The Department of Water, Land and Biodiversity Conservation and its employees expressly disclaims all liability or responsibility to any person using the information or advice. Information contained in this document is correct at the time of writing. Information contained in this document is correct at the time of writing. ISBN 978-1-921218-81-1 Preferred way to cite this publication Green G & Zulfic D, 2008, Summary of groundwater recharge estimates for the catchments of the Western -

Adelaide Hills Council Minutes of Ordinary Council Meeting Tuesday 28 August 2018 63 Mt Barker Road Stirling

171 ADELAIDE HILLS COUNCIL MINUTES OF ORDINARY COUNCIL MEETING TUESDAY 28 AUGUST 2018 63 MT BARKER ROAD STIRLING In Attendance Presiding Member: Mayor Bill Spragg Members: Councillor Ward Councillor Ron Nelson Manoah Councillor Jan-Claire Wisdom Councillor Ian Bailey Marble Hill Councillor Jan Loveday Councillor Kirrilee Boyd Mt Lofty Councillor Nathan Daniell Councillor John Kemp Councillor Lynton Vonow Onkaparinga Valley Councillor Andrew Stratford Councillor Linda Green Torrens Valley Councillor Malcolm Herrmann In Attendance: Andrew Aitken Chief Executive Officer Terry Crackett Director Corporate Services Peter Bice Director Infrastructure & Operations Marc Salver Director Development & Regulatory Services David Waters Director Community Capacity Lachlan Miller Executive Manager Governance & Performance John McArthur Manager Waste & Emergency Management Ashley Curtis Manager Civil Services Natalie Westover Manager Property Services Melanie Bright Manager Economic Development Steven Watson Governance & Risk Coordinator Renee O’Connor Sport & Recreation Planner Steven Brooks Biodiversity Officer Lynne Griffiths Community & Cultural Development Officer Pam Williams Minute Secretary 1. COMMENCEMENT The meeting commenced at 6.33pm. Mayor ____________________________________________________________ 25 September 2018 172 ADELAIDE HILLS COUNCIL MINUTES OF ORDINARY COUNCIL MEETING TUESDAY 28 AUGUST 2018 63 MT BARKER ROAD STIRLING 2. OPENING STATEMENT “Council acknowledges that we meet on the traditional lands of the Peramangk and Kaurna people and we recognise their connection with the land. We understand that we do not inherit the land from our ancestors but borrow it from our children and in this context the decisions we make should be guided by the principle that nothing we do should decrease our children’s ability to live on this land”. 3. APOLOGIES/LEAVE OF ABSENCE 3.1 Apology Nil 3.2 Leave of Absence Nil 3.3 Absent Nil 4. -

Fish Monitoring Across Regional Catchments of the Adelaide and Mount Lofty Ranges Region 2015–17

Fish monitoring across regional catchments of the Adelaide and Mount Lofty Ranges region 2015–17 David W. Schmarr, Rupert Mathwin and David L.M. Cheshire SARDI Publication No. F2018/000217-1 SARDI Research Report Series No. 990 SARDI Aquatics Sciences PO Box 120 Henley Beach SA 5022 August 2018 Schmarr, D. et al. (2018) Fish monitoring across regional catchments of the Adelaide and Mount Lofty Ranges region 2015–17 Fish monitoring across regional catchments of the Adelaide and Mount Lofty Ranges region 2015–17 Project David W. Schmarr, Rupert Mathwin and David L.M. Cheshire SARDI Publication No. F2018/000217-1 SARDI Research Report Series No. 990 August 2018 II Schmarr, D. et al. (2018) Fish monitoring across regional catchments of the Adelaide and Mount Lofty Ranges region 2015–17 This publication may be cited as: Schmarr, D.W., Mathwin, R. and Cheshire, D.L.M. (2018). Fish monitoring across regional catchments of the Adelaide and Mount Lofty Ranges region 2015-17. South Australian Research and Development Institute (Aquatic Sciences), Adelaide. SARDI Publication No. F2018/000217- 1. SARDI Research Report Series No. 990. 102pp. South Australian Research and Development Institute SARDI Aquatic Sciences 2 Hamra Avenue West Beach SA 5024 Telephone: (08) 8207 5400 Facsimile: (08) 8207 5415 http://www.pir.sa.gov.au/research DISCLAIMER The authors warrant that they have taken all reasonable care in producing this report. The report has been through the SARDI internal review process, and has been formally approved for release by the Research Chief, Aquatic Sciences. Although all reasonable efforts have been made to ensure quality, SARDI does not warrant that the information in this report is free from errors or omissions. -

Field River and Glenthorne Farm Ground to Forage for Food

YELLOW-RUMPED THORNBILL The Yellow-rumped Thornbill is a small insect eating bird which ocassionally eats seeds. It associates in small flocks, often flying from small shrubs down onto the Field River and Glenthorne Farm ground to forage for food. When disturbed, these birds alight back into the shrubs, revealing their bright yellow rumps. Seen in the open fields along the Field River, these birds will adapt to living close to suburbs provided adequate open space is Bird List preserved for them. They live in woodlands but can happily survive around mown The local open space of the southern suburbs is an important corridor linking the Mount Lofty Ranges to the sea. fields if sufficient native habitat remains. They have been seen in reasonable The variety of landscapes within this area provides ideal habitat for the varying needs of many different birds numbers near Hugh Johnson Reserve, Sheidow Park and along the Southern and because of this the opportunity exists to see many Australian birds close to our suburban homes. Expressway near Trott Park. We hope that when you are out walking, this bird list may assist you to identify some of the birds you see. YELLOW-TAILED BLACK COCKATOO Yellow-tailed Black Cockatoos are frequent visitors to the southern suburbs, looking for pine nuts in local trees after the breeding season has been completed elsewhere. These birds congregate in large flocks and are seen at certain times of the year in Reynella, in Sheidow Park and in 2007 about 200 appeared at Glenthorne Farm one Sunday morning as the Friends of Glenthorne were working. -

Torrens Lake Update: Summer 2020–21

Controlling blue-green algae in the lake has been most successful when releasing flows down the river – high flow rates, for a short duration, mix up and cool down the water – as well as benefiting the whole river system. Highbury Windsor Gardens Lochiel Park Catchment Monitoring Infrastructure Vale Park Felixstow management • Every 15 minutes, temperature, dissolved REMOVING LARGE ITEMS OF RUBBISH St Peters Flinders Park Adelaide oxygen and salinity, and weather conditions Adelaide • Gross pollutant traps on all stormwater Lockleys Hills • Removed over 3.5 tonnes Adelaide are measured from 3 permanent water of Carp directly entering the lake quality monitoring stations in the lake • Gross pollutant traps throughout • Erosion prevention and Gulf St • Twice weekly water quality monitoring the catchment, including on First, Vincent riverbank planting at 7 locations over summer Second, Third, Fourth and Fifth creeks • Woody weed removal + capturing over 5000 tonnes in the last • Weekly water quality monitoring along replanting with native two years the river – including the sea at the outlet plants along linear park • Floating boom on the river in St Peters • Twice yearly fish monitoring along the • Over 15,000 native aquatic river and around the lake MINIMISING NUTRIENTS IN THE LAKE plants placed in the lake • Duck feeding station in the lake closed • Regular dredging of the lake, • Aquatic plants added to take up nutrients 3 with over 3000m removed • Floating wetlands (aquatic plants grown on a floating platform) in 2017 being trialled -

Pristine Delivery by Post Code 2020.Xlsx

SA by Suburb South Australian Delivery Suburbs 2020 Postcode Suburb State Delivery Day 5159 Aberfoyle Park SA Friday 5000 Adelaide SA Friday 5950 Adelaide Airport SA Friday 5005 Adelaide University SA Friday 5014 Albert Park SA Friday 5014 Alberton SA Friday 5154 Aldgate SA Friday 5173 Aldinga SA Friday 5173 Aldinga Beach SA Friday 5009 Allenby Gardens SA Friday 5114 Andrews Farm SA Friday 5010 Angle Park SA Friday 5117 Angle Vale SA Friday 5043 Ascot Park SA Friday 5035 Ashford SA Friday 5137 Ashton SA Friday 5076 Athelstone SA Friday 5012 Athol Park SA Friday 5072 Auldana SA Friday 5242 Balhannah SA Friday 5242 Balhannah SA Friday 5091 Banksia Park SA Friday 5138 Basket Range SA Friday 5066 Beaumont SA Friday 5042 Bedford Park SA Friday 5052 Belair SA Friday 5050 Bellevue Heights SA Friday 5067 Beulah Park SA Friday 5009 Beverley SA Friday 5118 Bibaringa SA Friday 5153 Biggs Flat SA Friday 5015 Birkenhead SA Friday 5035 Black Forest SA Friday 5051 Blackwood SA Friday 5084 Blair Athol SA Friday 5084 Blair Athol West SA Friday 5114 Blakeview SA Friday 5171 Blewitt Springs SA Friday 5110 Bolivar SA Friday 5007 Bowden SA Friday 5153 Bradbury SA Friday 5109 Brahma Lodge SA Friday 5155 Bridgewater SA Friday 5048 Brighton SA Friday 5083 Broadview SA Friday 5007 Brompton SA Friday 5032 Brooklyn Park SA Friday 5062 Brown Hill Creek SA Friday 5118 Buchfelde SA Friday 5066 Burnside SA Friday 5110 Burton SA Friday 5038 Camden Park SA Friday 5074 Campbelltown SA Friday Page 1 of 9 5144 Carey Gully SA by Suburb SA Friday 5076 Castambul SA Friday