Transcript Prepared from a Tape Recording.] 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appendix File Anes 1988‐1992 Merged Senate File

Version 03 Codebook ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ CODEBOOK APPENDIX FILE ANES 1988‐1992 MERGED SENATE FILE USER NOTE: Much of his file has been converted to electronic format via OCR scanning. As a result, the user is advised that some errors in character recognition may have resulted within the text. MASTER CODES: The following master codes follow in this order: PARTY‐CANDIDATE MASTER CODE CAMPAIGN ISSUES MASTER CODES CONGRESSIONAL LEADERSHIP CODE ELECTIVE OFFICE CODE RELIGIOUS PREFERENCE MASTER CODE SENATOR NAMES CODES CAMPAIGN MANAGERS AND POLLSTERS CAMPAIGN CONTENT CODES HOUSE CANDIDATES CANDIDATE CODES >> VII. MASTER CODES ‐ Survey Variables >> VII.A. Party/Candidate ('Likes/Dislikes') ? PARTY‐CANDIDATE MASTER CODE PARTY ONLY ‐‐ PEOPLE WITHIN PARTY 0001 Johnson 0002 Kennedy, John; JFK 0003 Kennedy, Robert; RFK 0004 Kennedy, Edward; "Ted" 0005 Kennedy, NA which 0006 Truman 0007 Roosevelt; "FDR" 0008 McGovern 0009 Carter 0010 Mondale 0011 McCarthy, Eugene 0012 Humphrey 0013 Muskie 0014 Dukakis, Michael 0015 Wallace 0016 Jackson, Jesse 0017 Clinton, Bill 0031 Eisenhower; Ike 0032 Nixon 0034 Rockefeller 0035 Reagan 0036 Ford 0037 Bush 0038 Connally 0039 Kissinger 0040 McCarthy, Joseph 0041 Buchanan, Pat 0051 Other national party figures (Senators, Congressman, etc.) 0052 Local party figures (city, state, etc.) 0053 Good/Young/Experienced leaders; like whole ticket 0054 Bad/Old/Inexperienced leaders; dislike whole ticket 0055 Reference to vice‐presidential candidate ? Make 0097 Other people within party reasons Card PARTY ONLY ‐‐ PARTY CHARACTERISTICS 0101 Traditional Democratic voter: always been a Democrat; just a Democrat; never been a Republican; just couldn't vote Republican 0102 Traditional Republican voter: always been a Republican; just a Republican; never been a Democrat; just couldn't vote Democratic 0111 Positive, personal, affective terms applied to party‐‐good/nice people; patriotic; etc. -

The Politics of Charter School Growth and Sustainability in Harlem

REGIMES, REFORM, AND RACE: THE POLITICS OF CHARTER SCHOOL GROWTH AND SUSTAINABILITY IN HARLEM by Basil A. Smikle Jr. Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy under the Executive Committee of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2019 © 2019 Basil A. Smikle Jr. All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT REGIMES, REFORM, AND RACE: THE POLITICS OF CHARTER SCHOOL GROWTH AND SUSTAINABILITY IN HARLEM By Basil A. Smikle Jr. The complex and thorny relationship betWeen school-district leaders, sub-city political and community figures and teachers’ unions on the subject of charter schools- an interaction fraught with racially charged language and tactics steeped in civil rights-era mobilization - elicits skepticism about the motives of education reformers and their vieW of minority populations. In this study I unpack the local politics around tacit and overt racial appeals in support of NeW York City charter schools with particular attention to Harlem, NeW York and periods when the sustainability of these schools, and long-term education reforms, were endangered by changes in the political and legislative landscape. This dissertation ansWers tWo key questions: How did the Bloomberg-era governing coalition and charter advocates in NeW York City use their political influence and resources to expand and sustain charter schools as a sector; and how does a community with strong historic and cultural narratives around race, education and political activism, respond to attempts to enshrine externally organized school reforms? To ansWer these questions, I employ a case study analysis and rely on Regime Theory to tell the story of the Mayoral administration of Michael Bloomberg and the cadre of charter leaders, philanthropies and wealthy donors whose collective activity created a climate for growth of the sector. -

Deals for Trade Votes Gone Bad

Deals for Trade Votes Gone Bad June 2005 © 2005 by Public Citizen’s Global Trade Watch. All rights reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photography, recording, or by information exchange and retrieval systems, without written permission from the authors. Public Citizen is a nonprofit membership organization in Washington, D.C., dedicated to advancing consumer rights through lobbying, litigation, research, publications and information services. Since its founding by Ralph Nader in 1971, Public Citizen has fought for consumer rights in the marketplace, for safe and secure health care, for fair trade, for clean and safe energy sources, and for corporate and government accountability. Visit our web page at http://www.citizen.org. Acknowledgments: This report was written by Todd Tucker, Brandon Wu and Alyssa Prorok. The authors would like to thank Paul Adler, Eliza Brinkmeyer, Tony Corbo, Elizabeth Drake, Susan Ellsworth, Lina Gomez, David Kamin, Patricia Lovera, Travis McArthur, Nanine Meiklejohn, Kathy Ozer, Tyson Slocum, Tom “Smitty” Smith, Margarete Strand, Jamie Strawbridge, Michele Varnhagen, Jeff Vogt, Lori Wallach, and David Waskow for their help with this document, as well as the authors of previous Public Citizen’s Global Trade Watch deals reports, including Gabriella Boyer, Mike Dolan, Tamar Malley, Chris McGinn, Robert Naiman, Darshana Patel, and Patrick Woodall. Special thanks go to James Meehan for help with the title logo. We also thank -

The African-American Church, Political Activity, and Tax Exemption

JAMES_EIC 1/11/2007 9:47:35 PM The African-American Church, Political Activity, and Tax Exemption Vaughn E. James∗ ABSTRACT Ever since its inception during slavery, the African-American Church has served as an advocate for the socio-economic improve- ment of this nation’s African-Americans. Accordingly, for many years, the Church has been politically active, serving as the nurturing ground for several African-American politicians. Indeed, many of the country’s early African-American legislators were themselves mem- bers of the clergy of the various denominations that constituted the African-American Church. In 1934, Congress amended the Internal Revenue Code to pro- hibit tax-exempt entities—including churches and other houses of worship—from allowing lobbying to constitute a “substantial part” of their activities. In 1954, Congress further amended the Code to place an absolute prohibition on political campaigning by these tax-exempt organizations. While these amendments did not specifically target churches and other houses of worship, they have had a chilling effect on efforts by these entities to fulfill their mission. This chilling effect is felt most acutely by the African-American Church, a church estab- lished to preach the Gospel and engage in activities which would im- prove socio-economic conditions for the nation’s African-Americans. This Article discusses the efforts made by the African-American Church to remain faithful to its mission and the inadvertent attempts ∗ Professor of Law, Texas Tech University School of Law. The author wishes to thank Associate Dean Brian Shannon, Texas Tech University School of Law; Profes- sor Christian Day, Syracuse University College of Law; Professor Dwight Aarons, Uni- versity of Tennessee College of Law; Ms. -

REVIEW of INTERNAL REVENUE CODE SECTION 501(C)(3) REQUIREMENTS for RELIGIOUS ORGANIZATIONS

REVIEW OF INTERNAL REVENUE CODE SECTION 501(c)(3) REQUIREMENTS FOR RELIGIOUS ORGANIZATIONS HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON OVERSIGHT OF THE COMMITTEE ON WAYS AND MEANS HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED SEVENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION MAY 14, 2002 Serial No. 107–69 Printed for the use of the Committee on Ways and Means ( U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 80–331 WASHINGTON : 2002 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate 11-MAY-2000 01:17 Aug 15, 2002 Jkt 010199 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 W:\DISC\80331.XXX txed01 PsN: txed01 COMMITTEE ON WAYS AND MEANS BILL THOMAS, California, Chairman PHILIP M. CRANE, Illinois CHARLES B. RANGEL, New York E. CLAY SHAW, JR., Florida FORTNEY PETE STARK, California NANCY L. JOHNSON, Connecticut ROBERT T. MATSUI, California AMO HOUGHTON, New York WILLIAM J. COYNE, Pennsylvania WALLY HERGER, California SANDER M. LEVIN, Michigan JIM MCCRERY, Louisiana BENJAMIN L. CARDIN, Maryland DAVE CAMP, Michigan JIM MCDERMOTT, Washington JIM RAMSTAD, Minnesota GERALD D. KLECZKA, Wisconsin JIM NUSSLE, Iowa JOHN LEWIS, Georgia SAM JOHNSON, Texas RICHARD E. NEAL, Massachusetts JENNIFER DUNN, Washington MICHAEL R. MCNULTY, New York MAC COLLINS, Georgia WILLIAM J. JEFFERSON, Louisiana ROB PORTMAN, Ohio JOHN S. TANNER, Tennessee PHIL ENGLISH, Pennsylvania XAVIER BECERRA, California WES WATKINS, Oklahoma KAREN L. THURMAN, Florida J.D. HAYWORTH, Arizona LLOYD DOGGETT, Texas JERRY WELLER, Illinois EARL POMEROY, North Dakota KENNY C. -

Special Election Dates

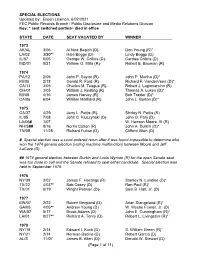

SPECIAL ELECTIONS Updated by: Eileen Leamon, 6/02/2021 FEC Public Records Branch / Public Disclosure and Media Relations Division Key: * seat switched parties/- died in office STATE DATE SEAT VACATED BY WINNER 1973 AK/AL 3/06 Al Nick Begich (D)- Don Young (R)* LA/02 3/20** Hale Boggs (D)- Lindy Boggs (D) IL/07 6/05 George W. Collins (D)- Cardiss Collins (D) MD/01 8/21 William O. Mills (R)- Robert E. Bauman (R) 1974 PA/12 2/05 John P. Saylor (R)- John P. Murtha (D)* MI/05 2/18 Gerald R. Ford (R) Richard F. VanderVeen (D)* CA/13 3/05 Charles M. Teague (R)- Robert J. Lagomarsino (R) OH/01 3/05 William J. Keating (R) Thomas A. Luken (D)* MI/08 4/16 James Harvey (R) Bob Traxler (D)* CA/06 6/04 William Mailliard (R) John L. Burton (D)* 1975 CA/37 4/29 Jerry L. Pettis (R)- Shirley N. Pettis (R) IL/05 7/08 John C. Kluczynski (D)- John G. Fary (D) LA/06# 1/07 W. Henson Moore, III (R) NH/S## 9/16 Norris Cotton (R) John A. Durkin (D)* TN/05 11/25 Richard Fulton (D) Clifford Allen (D) # Special election was a court-ordered rerun after it was found impossible to determine who won the 1974 general election (voting machine malfunction) between Moore and Jeff LaCaze (D). ## 1974 general election between Durkin and Louis Wyman (R) for the open Senate seat was too close to call and the Senate refused to seat either candidate. Special election was held in September 1975. -

African-American Mothers' Choice

IN SEARCH OF SATISFACTION: AFRICAN-AMERICAN MOTHERS’ CHOICE FOR FAITH-BASED EDUCATION DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Lenora Barnes-Wright, M.P.H. ***** The Ohio State University 2004 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Seymour Kleinman, Advisor Professor Ralph Gardner ______________________________ Professor Valerie Lee Adviser Educational Policy and Leadership ABSTRACT This research provides an in-depth view of the decision-making process used by African- American parents when enrolling their children in church/ faith-based schools. The specific questions guiding this research project were: What do African-American mothers believe are the primary purposes of education for their children? Why have some African-American families chosen to not enroll their daughters and sons in public schools? What are the factors that lead individual African-American mothers to look to faith-based education for their children’s education? What specific criteria do African-American mothers use when considering and selecting an educational program for their children? What sacrifices are African-American families willing to make in order to secure a quality educational experience for their children? This study was conducted using the Delphi Method which requires the establishment of a "panel of experts" with whom the research questions can be explored. African-American mothers or other primary caregivers who 1) attended a selected African-American protestant congregation; and, 2) had children enrolled in a faith-based school in grades ii kindergarten through eight, were recruited to serve on the panel. Nineteen mothers agreed to serve as "expert-participants." The Delphi process included an initial round during which expert-participants responded to an 8-item open-ended questionnaire that was issued online. -

Finding Aid to the Historymakers ® Video Oral History with the Honorable Reverend Dr

Finding Aid to The HistoryMakers ® Video Oral History with The Honorable Reverend Dr. Suzan Johnson Cook Overview of the Collection Repository: The HistoryMakers®1900 S. Michigan Avenue Chicago, Illinois 60616 [email protected] www.thehistorymakers.com Creator: Cook, Suzan Johnson, 1957- Title: The HistoryMakers® Video Oral History Interview with The Honorable Reverend Dr. Suzan Johnson Cook, Dates: December 1, 2005 and July 24, 2007 Bulk Dates: 2005 and 2007 Physical 6 Betacame SP videocasettes (2:44:24). Description: Abstract: Pastor The Honorable Reverend Dr. Suzan Johnson Cook (1957 - ) was the first African American woman to be named pastor by the American Baptist Association and the first woman chaplain for the New York City Police Department. She is co-founder and chief operating officer of JONCO Productions, Inc., a sales, management, and diversity firm, and is the author of the bestselling, "Too Blessed to Be Stressed," released in 2002. Cook was interviewed by The HistoryMakers® on December 1, 2005 and July 24, 2007, in New York, New York. This collection is comprised of the original video footage of the interview. Identification: A2005_251 Language: The interview and records are in English. Biographical Note by The HistoryMakers® Religious leader and corporate entrepreneur Suzan Johnson Cook was born January 28, 1957, in New York City. Her mother was a schoolteacher and her father, a trolley car driver. They founded a security guard business that moved the family from a Harlem, New York, tenement to a home in the Gunn Hill section of father, a trolley car driver. They founded a security guard business that moved the family from a Harlem, New York, tenement to a home in the Gunn Hill section of the Bronx, New York. -

Have American Churches Failed to Satisfy the Requirements for the Religious Tax Exemption?

The Catholic Lawyer Volume 43 Number 1 Volume 43, Spring 2004, Number 1 Article 4 Reaping Where They Have Not Sowed: Have American Churches Failed To Satisfy the Requirements for the Religious Tax Exemption? Vaughn E. James Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.stjohns.edu/tcl Part of the Catholic Studies Commons, and the Tax Law Commons This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Catholic Lawyer by an authorized editor of St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REAPING WHERE THEY HAVE NOT SOWED: HAVE AMERICAN CHURCHES FAILED TO SATISFY THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE RELIGIOUS TAX EXEMPTION? VAUGHN E. JAMES* INTRODUCTION 'Make no mistake: God is not mocked, for a person will reap only what he sows." 1 Section 501(a) of the Internal Revenue Code (IRC) provides for federal tax exemption for organizations described in § 501(c) or (d) or in § 401(a).2 Section 501(c)(3) lists the so-called "charitable organizations" that benefit from the tax exemption provided for by § 501(a): Corporations, and any community chest, fund, or foundation, organized and operated exclusively for religious, charitable, scientific, testing for public safety, literary, or educational purposes, or to foster national or international amateur sports competition (but only if no part of its activities involve the provision of athletic facilities or equipment), or for the prevention of cruelty to children or animals. ....3 Associate Professor of Law, Texas Tech University School of Law. -

Finding Aid to the Historymakers ® Video Oral History with the Honorable Reverend Dr

Finding Aid to The HistoryMakers ® Video Oral History with The Honorable Reverend Dr. Floyd Flake Overview of the Collection Repository: The HistoryMakers®1900 S. Michigan Avenue Chicago, Illinois 60616 [email protected] www.thehistorymakers.com Creator: Flake, Floyd Title: The HistoryMakers® Video Oral History Interview with The Honorable Reverend Dr. Floyd Flake, Dates: September 15, 2001 Bulk Dates: 2001 Physical 6 Betacame SP videocasettes (2:41:35). Description: Abstract: U.S. congressman and minister The Honorable Reverend Dr. Floyd Flake (1945 - ) is the pastor of The Greater Allen Cathedral of New York and a former member of the U.S. House of Representatives. Under Flake's leadership, the church's membership has grown to more than 13,000, complete with a private school, senior citizens center and hundreds of housing units for its members and other community residents. Flake was interviewed by The HistoryMakers® on September 15, 2001, in Queens, New York. This collection is comprised of the original video footage of the interview. Identification: A2001_032 Language: The interview and records are in English. Biographical Note by The HistoryMakers® Reverend Dr. Floyd H. Flake was born on January 30, 1945. He grew up in segregated Houston as one of fifteen children to Robert Flake, Sr. and Rosie Lee Johnson-Flake. Their small two bedroom house lacked running water. Flake was heavily influenced by his parents' strong moral beliefs and by excellent teachers who challenged him. heavily influenced by his parents' strong moral beliefs and by excellent teachers who challenged him. After high school, Flake attended Wilberforce University, obtaining his B.A. -

Resignations

CHAPTER 37 Resignations A. Introduction § 1. Scope of Chapter § 2. Background B. Resignation of a Member From the House § 3. Procedures and Forms § 4. Reason for Resignation; Inclusion in Letter of Res- ignation § 5. Conditional Resignations; Timing C. Resignations From Committees and Delegations § 6. Procedures and Forms § 7. Reason for Resignation § 8. Resignations From Delegations and Commissions D. Resignations of Officers, Officials, and Employees § 9. Procedure § 10. Tributes Commentary and editing by John V. Sullivan, J.D., Andrew S. Neal, J.D., and Robert W. Cover, J.D.; manuscript editing by Deborah Woodard Khalili. 349 VerDate 0ct 09 2002 14:45 Jan 25, 2011 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00361 Fmt 8890 Sfmt 8890 F:\PRECEDIT\VOL17\17COMP~1 27-2A VerDate 0ct 09 2002 14:45 Jan 25, 2011 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00362 Fmt 8890 Sfmt 8890 F:\PRECEDIT\VOL17\17COMP~1 27-2A Resignations A. Introduction § 1. Scope of Chapter fective on its stated terms and or- dinarily may not be withdrawn.(1) This chapter covers resignations 1. 2 Hinds’ Precedents § 1213 and 6 from the House of Representatives Cannon’s Precedents § 65 (address- (with occasional illustrative in- ing whether a proposal to withdraw stances from the Senate). Also ad- a resignation may be privileged). Ex- dressed are resignations from tracts from the Judiciary Committee report in 6 Cannon’s Precedents § 65 committees, boards, and commis- state without citation that resigna- sions and resignations of certain tions are ‘‘self-acting’’ and may not officers and staff of the House. be withdrawn. In one case a Member Because the process of resigna- was not permitted by the House to withdraw a resignation. -

The Honorable Xavier Becerra Secretary of Health and Human Services-Designate U.S

March 2, 2021 The Honorable Xavier Becerra Secretary of Health and Human Services-Designate U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 200 Independence Avenue, S.W. Washington, D.C. 20201 And The Honorable Norris Cochran Acting Secretary of Health and Human Services U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 200 Independence Avenue, S.W. Washington, D.C. 20201 THRU African Methodist Episcopal Church African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church American Baptist Churches, USA Berean Missionary Baptist Association, Inc. Bible Way Church World-Wide, Inc. Christian Methodist Episcopal Church Church of God in Christ Full Gospel Baptist Church Fellowship International Greater Mount Calvary Holy Church House of God International Bible Way Church of Jesus Christ International Council of Community Churches Mt. Calvary Holy Church of America Mount Sinai Holy Church of America, Inc. National Baptist Convention, USA, Inc. National Baptist Convention of America International, Inc. National Council of Churches National Primitive Baptist Convention, USA, Inc. Pentecostal Assemblies of the World, Inc. Progressive National Baptist Convention, Inc. The Potter's House Church The Union of Black Episcopalian Full Gospel Baptist Church Fellowship International Dear Secretary Xavier Becerra, The National Black Church Initiative (NCBI), a coalition of 150,000 African American and Latino churches, has a membership of 27.7 million African American and Latino churchgoers supporting Dr. Joshua Sharfstein to become the next commissioner of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). There are several qualified candidates for this position; but we strongly believe that Dr. Sharfstein’s broad-based knowledge and his inclusive, culturally sensitive approach to public health will produce appropriate and effective courses of action in the ever-changing environment of the pandemic.