Political Behavior/Participation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The George Komure Elementary School High Schooler Emily Isakari Headed Back to Her Booth at the School’S Festival

PAGE 4 Animeʼs uber populatiy. PAGE 9 Erika Fong the WHATʼS Pink Power Ranger IN A NAME? Emily Isakari wants the world to know about George Komure. PAGE 10 JACL youth in action PAGE 3 at youth summit. # 3169 VOL. 152, NO. 11 ISSN: 0030-8579 WWW.PACIFICCITIZEN.ORG June 17-30, 2011 2 june 17-30, 2011 LETTERS/COMMENTARY PACIFIC CITIZEN HOW TO REACH US E-mail: [email protected] LETTERS TO THE EDITOR Online: www.pacificcitizen.org Tel: (213) 620-1767 Food Issue: Yummy Fax: (213) 620-1768 Power of Words Resolution Connecting JACLers Mail: 250 E. First Street, Suite 301 The “Power of Words” handbook, which is being developed to Across the Country Great issue! Made me hungry Los Angeles, CA 90012 implement the Power of Words resolution passed at the 2010 Chicago just reading about the passion and StaFF JACL convention, was sent electronically to all JACL chapter Since the days when reverence these cooks have for Executive Editor Caroline Y. Aoyagi-Stom presidents recently. I would like all JACL members to take a close headquarters was in Utah and all food. How about another special look at this handbook, especially the section titled: “Which Words Are the folks involved in suffering issue (or column) featuring Assistant Editor Lynda Lin Problematic? … And Which Words Should We Promote?” during World War II, many of some of our members and their Who labeled these words as “problematic?” The words are them our personal friends, my interesting hobbies? Reporter euphemisms and we should not use them. There are words that can be wife Nellie and I have enjoyed and Keep up the wonderful work; I Nalea J. -

Appendix File Anes 1988‐1992 Merged Senate File

Version 03 Codebook ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ CODEBOOK APPENDIX FILE ANES 1988‐1992 MERGED SENATE FILE USER NOTE: Much of his file has been converted to electronic format via OCR scanning. As a result, the user is advised that some errors in character recognition may have resulted within the text. MASTER CODES: The following master codes follow in this order: PARTY‐CANDIDATE MASTER CODE CAMPAIGN ISSUES MASTER CODES CONGRESSIONAL LEADERSHIP CODE ELECTIVE OFFICE CODE RELIGIOUS PREFERENCE MASTER CODE SENATOR NAMES CODES CAMPAIGN MANAGERS AND POLLSTERS CAMPAIGN CONTENT CODES HOUSE CANDIDATES CANDIDATE CODES >> VII. MASTER CODES ‐ Survey Variables >> VII.A. Party/Candidate ('Likes/Dislikes') ? PARTY‐CANDIDATE MASTER CODE PARTY ONLY ‐‐ PEOPLE WITHIN PARTY 0001 Johnson 0002 Kennedy, John; JFK 0003 Kennedy, Robert; RFK 0004 Kennedy, Edward; "Ted" 0005 Kennedy, NA which 0006 Truman 0007 Roosevelt; "FDR" 0008 McGovern 0009 Carter 0010 Mondale 0011 McCarthy, Eugene 0012 Humphrey 0013 Muskie 0014 Dukakis, Michael 0015 Wallace 0016 Jackson, Jesse 0017 Clinton, Bill 0031 Eisenhower; Ike 0032 Nixon 0034 Rockefeller 0035 Reagan 0036 Ford 0037 Bush 0038 Connally 0039 Kissinger 0040 McCarthy, Joseph 0041 Buchanan, Pat 0051 Other national party figures (Senators, Congressman, etc.) 0052 Local party figures (city, state, etc.) 0053 Good/Young/Experienced leaders; like whole ticket 0054 Bad/Old/Inexperienced leaders; dislike whole ticket 0055 Reference to vice‐presidential candidate ? Make 0097 Other people within party reasons Card PARTY ONLY ‐‐ PARTY CHARACTERISTICS 0101 Traditional Democratic voter: always been a Democrat; just a Democrat; never been a Republican; just couldn't vote Republican 0102 Traditional Republican voter: always been a Republican; just a Republican; never been a Democrat; just couldn't vote Democratic 0111 Positive, personal, affective terms applied to party‐‐good/nice people; patriotic; etc. -

The Politics of Charter School Growth and Sustainability in Harlem

REGIMES, REFORM, AND RACE: THE POLITICS OF CHARTER SCHOOL GROWTH AND SUSTAINABILITY IN HARLEM by Basil A. Smikle Jr. Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy under the Executive Committee of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2019 © 2019 Basil A. Smikle Jr. All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT REGIMES, REFORM, AND RACE: THE POLITICS OF CHARTER SCHOOL GROWTH AND SUSTAINABILITY IN HARLEM By Basil A. Smikle Jr. The complex and thorny relationship betWeen school-district leaders, sub-city political and community figures and teachers’ unions on the subject of charter schools- an interaction fraught with racially charged language and tactics steeped in civil rights-era mobilization - elicits skepticism about the motives of education reformers and their vieW of minority populations. In this study I unpack the local politics around tacit and overt racial appeals in support of NeW York City charter schools with particular attention to Harlem, NeW York and periods when the sustainability of these schools, and long-term education reforms, were endangered by changes in the political and legislative landscape. This dissertation ansWers tWo key questions: How did the Bloomberg-era governing coalition and charter advocates in NeW York City use their political influence and resources to expand and sustain charter schools as a sector; and how does a community with strong historic and cultural narratives around race, education and political activism, respond to attempts to enshrine externally organized school reforms? To ansWer these questions, I employ a case study analysis and rely on Regime Theory to tell the story of the Mayoral administration of Michael Bloomberg and the cadre of charter leaders, philanthropies and wealthy donors whose collective activity created a climate for growth of the sector. -

Deals for Trade Votes Gone Bad

Deals for Trade Votes Gone Bad June 2005 © 2005 by Public Citizen’s Global Trade Watch. All rights reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photography, recording, or by information exchange and retrieval systems, without written permission from the authors. Public Citizen is a nonprofit membership organization in Washington, D.C., dedicated to advancing consumer rights through lobbying, litigation, research, publications and information services. Since its founding by Ralph Nader in 1971, Public Citizen has fought for consumer rights in the marketplace, for safe and secure health care, for fair trade, for clean and safe energy sources, and for corporate and government accountability. Visit our web page at http://www.citizen.org. Acknowledgments: This report was written by Todd Tucker, Brandon Wu and Alyssa Prorok. The authors would like to thank Paul Adler, Eliza Brinkmeyer, Tony Corbo, Elizabeth Drake, Susan Ellsworth, Lina Gomez, David Kamin, Patricia Lovera, Travis McArthur, Nanine Meiklejohn, Kathy Ozer, Tyson Slocum, Tom “Smitty” Smith, Margarete Strand, Jamie Strawbridge, Michele Varnhagen, Jeff Vogt, Lori Wallach, and David Waskow for their help with this document, as well as the authors of previous Public Citizen’s Global Trade Watch deals reports, including Gabriella Boyer, Mike Dolan, Tamar Malley, Chris McGinn, Robert Naiman, Darshana Patel, and Patrick Woodall. Special thanks go to James Meehan for help with the title logo. We also thank -

California Government

330673_fm.qxd 02/02/05 1:04 PM Page i California Government CengageNot for Learning Reprint 330673_fm.qxd 02/02/05 1:04 PM Page ii CengageNot for Learning Reprint 330673_fm.qxd 02/02/05 1:04 PM Page iii ######## California Government Fourth Edition John L. Korey California State Polytechnic University, Pomona CengageNot for Learning Reprint Houghton Mifflin Company Boston New York 330673_fm.qxd 02/02/05 1:04 PM Page iv DEDICATION To Mary, always and to the newest family members— Welcome to California Publisher: Charles Hartford Sponsoring Editor: Katherine Meisenheimer Assistant Editor: Christina Lembo Editorial Assistant: Kristen Craib Associate Project Editor: Teresa Huang Editorial Assistant: Jake Perry Senior Art and Design Coordinator: Jill Haber Senior Photo Editor: Jennifer Meyer Dare Senior Composition Buyer: Sarah Ambrose Manufacturing Coordinator: Carrie Wagner Executive Marketing Manager: Nicola Poser Marketing Associate: Kathleen Mellon Cover image: Primary California Photography, © Harold Burch, New York City. California State Bear Photo © Bob Rowan, Progressive Image/CORBIS. Copyright © 2006 by Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system without the prior written permission of Houghton Mifflin Company unless such copying is expressly permitted by federal copyright law. Address inquiries to College Permissions, Houghton Mifflin -

The African-American Church, Political Activity, and Tax Exemption

JAMES_EIC 1/11/2007 9:47:35 PM The African-American Church, Political Activity, and Tax Exemption Vaughn E. James∗ ABSTRACT Ever since its inception during slavery, the African-American Church has served as an advocate for the socio-economic improve- ment of this nation’s African-Americans. Accordingly, for many years, the Church has been politically active, serving as the nurturing ground for several African-American politicians. Indeed, many of the country’s early African-American legislators were themselves mem- bers of the clergy of the various denominations that constituted the African-American Church. In 1934, Congress amended the Internal Revenue Code to pro- hibit tax-exempt entities—including churches and other houses of worship—from allowing lobbying to constitute a “substantial part” of their activities. In 1954, Congress further amended the Code to place an absolute prohibition on political campaigning by these tax-exempt organizations. While these amendments did not specifically target churches and other houses of worship, they have had a chilling effect on efforts by these entities to fulfill their mission. This chilling effect is felt most acutely by the African-American Church, a church estab- lished to preach the Gospel and engage in activities which would im- prove socio-economic conditions for the nation’s African-Americans. This Article discusses the efforts made by the African-American Church to remain faithful to its mission and the inadvertent attempts ∗ Professor of Law, Texas Tech University School of Law. The author wishes to thank Associate Dean Brian Shannon, Texas Tech University School of Law; Profes- sor Christian Day, Syracuse University College of Law; Professor Dwight Aarons, Uni- versity of Tennessee College of Law; Ms. -

REVIEW of INTERNAL REVENUE CODE SECTION 501(C)(3) REQUIREMENTS for RELIGIOUS ORGANIZATIONS

REVIEW OF INTERNAL REVENUE CODE SECTION 501(c)(3) REQUIREMENTS FOR RELIGIOUS ORGANIZATIONS HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON OVERSIGHT OF THE COMMITTEE ON WAYS AND MEANS HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED SEVENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION MAY 14, 2002 Serial No. 107–69 Printed for the use of the Committee on Ways and Means ( U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 80–331 WASHINGTON : 2002 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate 11-MAY-2000 01:17 Aug 15, 2002 Jkt 010199 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 W:\DISC\80331.XXX txed01 PsN: txed01 COMMITTEE ON WAYS AND MEANS BILL THOMAS, California, Chairman PHILIP M. CRANE, Illinois CHARLES B. RANGEL, New York E. CLAY SHAW, JR., Florida FORTNEY PETE STARK, California NANCY L. JOHNSON, Connecticut ROBERT T. MATSUI, California AMO HOUGHTON, New York WILLIAM J. COYNE, Pennsylvania WALLY HERGER, California SANDER M. LEVIN, Michigan JIM MCCRERY, Louisiana BENJAMIN L. CARDIN, Maryland DAVE CAMP, Michigan JIM MCDERMOTT, Washington JIM RAMSTAD, Minnesota GERALD D. KLECZKA, Wisconsin JIM NUSSLE, Iowa JOHN LEWIS, Georgia SAM JOHNSON, Texas RICHARD E. NEAL, Massachusetts JENNIFER DUNN, Washington MICHAEL R. MCNULTY, New York MAC COLLINS, Georgia WILLIAM J. JEFFERSON, Louisiana ROB PORTMAN, Ohio JOHN S. TANNER, Tennessee PHIL ENGLISH, Pennsylvania XAVIER BECERRA, California WES WATKINS, Oklahoma KAREN L. THURMAN, Florida J.D. HAYWORTH, Arizona LLOYD DOGGETT, Texas JERRY WELLER, Illinois EARL POMEROY, North Dakota KENNY C. -

Wtareg Chisinau Speakers

Taxpayers Regional Forum Chisinau, March 28th&29th, 2019 Speakers Daniel Bunn Director of Global Projects, Tax Foundation Daniel Bunn researches international tax issues with a focus on tax policy in Europe. Prior to joining the Tax Foundation, Daniel worked in the United States Senate at the Joint Economic Committee as part of Senator Mike Lee’s (R-UT) Social Capital Project and on the policy staff for both Senator Lee and Senator Tim Scott (R-SC). In his time in the Senate, Daniel developed legislative initiatives on tax, trade, regulatory, and budget policy. He has a master’s degree in Economic Policy from Central European University in Budapest, Hungary, and a bachelor’s degree in Business Administration from North Greenville University in South Carolina. Daniel lives in Halethorpe, Maryland, with his wife and their three children. Andreas Hellmann Program Manager, Americans for Tax Reform Andreas Hellmann is a Program Manager at Americans for Tax Reform (ATR), a Washington, D.C. based taxpayer advocacy and policy research organization founded in 1985 by Grover Norquist. His focus are issues of international taxation like the digital services tax. He is also responsible for building coalitions with a focus on Europe. You can follow him on Twitter @ahellmann or reach him by email at [email protected]. Scott A. Hodge President, Tax Foundation Scott A. Hodge is president of the Tax Foundation in Washington, D.C., one of the most influential organizations on tax policy in Washington and in state capitals. During his 17 years leading the Tax Foundation, he has built the Tax Foundation’s Taxes and Growth (TAG) Dynamic Modeling program which has normalized dynamic scoring as an accepted tool for analyzing tax policy. -

Instructions ·To Voters

COUNTY OF SACRAMENTO - GENERAL ELECTION TUESDAY, NOVEMBER 3, 1998 .INSTRUCTIONS ·TO VOTERS STATE Vote for One PUNCH OUT OFFICIAL BALLOT ONLY WITH GOVERNOR - GLORIA ESTELA LA AlVA VOTING INSTRUMENT ATTACHED TO VOTING DEVICE, 4 Newspaper Printer Peace and Freedom . DAN LUNGREN NEVER WITH PEN OR P.ENCIL. 5 California Attorney General Republican NATHAN E. JOHNSON 6 Public Transit Worker American Independent To vote for a canCrldate whose name appears in the Sample Official Ballot, DAN HAMBURG 7 . Educator Green punch the official ballot· at the point of the arrow opposite the number HAROLD H. BLOOMFIELD which corresponds to that ~didate. Where two or more candidates for 8 Physician/ Author/Educator Natural Law STEVE W. KUBBY the same office are to be elected, punch the official ballot at the point of Libertarian the arrow opposite the number which corresponds to' those candidates. 9 Publisher and Author GRAY DAVIS · The number of pun:hes made must not exceed the number of candidates 10 Lieutenant Governor of the State of California Democratic - to be elected. -- - =-- · - ---" '·-~.--~ . :-- -------, - - . Vote for One LIEUTENANT GOVERNOR To vote for a cancidate for Chief Justice of California; Associate Justice of THOMAS M. TRYON the Supreme Col.lt; Presiding justice; Court of Appeal; or Associate 12 County Supervisor/Rancher Libertarian Justice, Court of Ai>peal, punch the ballot card in the hole at the point of TIM LESLIE ·13 Republican the arrow to the right of the number which corresponds with "YES." To . Senator/Businessman CRUZ M. BUSTAMANTE · · vote against the caldidate, punch the ballot card in the hole at the point 14 Lawmaker · Democratic of the arrow to the right of the number which Corresponds with "NO." JAMES J. -

Priorities for the Next Administration

Grid Resilience: Priorities for the Next Administration www.gridresilience.org Commissioners Co-Chair Co-Chair Commissioner Commissioner General Wesley Clark Congressman Darrell Issa Norman Augustine General Paul Kern (USA, ret.) (R-CA, 2001-2019) (USA, ret.) Commissioner Commissioner Commissioner Special Advisor Kevin Knobloch Gueta Maria Mezzetti, Daniel Poneman John Dodson, Esq. Thayer Energy Research Team, AUI • Bri-Mathias Hodge, University of Colorado Boulder and Adam Cohen (Executive Director of the NCGR), Adam Reed, National Renewable Energy Laboratory Peter Kelly-Detwiler, David Catarious, Matt Schaub, • Eliza Hotchkiss, National Renewable Energy Laboratory Kevin Doran • Cynthia Hsu, National Rural Electric Cooperative Subject Matter Experts Association The Commission extends its gratitude to the following energy subject matter experts, who donated their time • Joshua Johnson, LSI to be interviewed for this report. The opinions and • Hank Kenchington, U.S. Department of Energy (fmr.) recommendations of the Commission do not imply endorsement from any of the experts interviewed. • Jeffrey Logan, National Renewable Energy Laboratory • Richard Mignogna, Renewable & Alternative Energy • Morgan Bazilian, Colorado School of Mines Management • Michael Borcherding, AUI • Edward T. (Tom) Morehouse, Executive Advisor to the • Gerry Cauley, Siemens Energy Business Advisory National Renewable Energy Laboratory • Michael Coe, U.S. Department of Energy • Chris Nelder, Rocky Mountain Institute and The Energy Transition Show • Christopher Clack, -

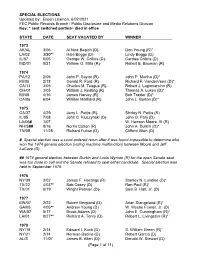

Special Election Dates

SPECIAL ELECTIONS Updated by: Eileen Leamon, 6/02/2021 FEC Public Records Branch / Public Disclosure and Media Relations Division Key: * seat switched parties/- died in office STATE DATE SEAT VACATED BY WINNER 1973 AK/AL 3/06 Al Nick Begich (D)- Don Young (R)* LA/02 3/20** Hale Boggs (D)- Lindy Boggs (D) IL/07 6/05 George W. Collins (D)- Cardiss Collins (D) MD/01 8/21 William O. Mills (R)- Robert E. Bauman (R) 1974 PA/12 2/05 John P. Saylor (R)- John P. Murtha (D)* MI/05 2/18 Gerald R. Ford (R) Richard F. VanderVeen (D)* CA/13 3/05 Charles M. Teague (R)- Robert J. Lagomarsino (R) OH/01 3/05 William J. Keating (R) Thomas A. Luken (D)* MI/08 4/16 James Harvey (R) Bob Traxler (D)* CA/06 6/04 William Mailliard (R) John L. Burton (D)* 1975 CA/37 4/29 Jerry L. Pettis (R)- Shirley N. Pettis (R) IL/05 7/08 John C. Kluczynski (D)- John G. Fary (D) LA/06# 1/07 W. Henson Moore, III (R) NH/S## 9/16 Norris Cotton (R) John A. Durkin (D)* TN/05 11/25 Richard Fulton (D) Clifford Allen (D) # Special election was a court-ordered rerun after it was found impossible to determine who won the 1974 general election (voting machine malfunction) between Moore and Jeff LaCaze (D). ## 1974 general election between Durkin and Louis Wyman (R) for the open Senate seat was too close to call and the Senate refused to seat either candidate. Special election was held in September 1975. -

Wilson Wins; IV : Kopeikin, Dobberteen

■ Props Tate Beating; ‘Big Green’ Falls, Term Limits’ possibly passed/Page 3 ■ Gridiron Hype: The Nexus’ Annual Homecoming Supplement Kicks/Page 1A Daily Nexus Volume 71, No. 44 Wednesday, November 7,1990 University of California, Santa Barbara Two Sections, 24 Pages Wilson Wins; I.V : Kopeikin, Dobberteen Californians Put Senator Wilson in State Capitol; Feinstein Ends ‘Triathlon’ By Larry Speer Staff Writer W Republican Senator Pete Wilson was elected Ca lifornia’s 36th Governor Tuesday, narrowly defeat ing Democratic challenger Dianne Feinstein and becoming the first Republican in almost 40 years to follow an incumbent Republican into the gover nor’s mansion. With more than 4 million votes counted and v /: fewer than 100 precincts unreported, Wilson led RESULTS Feinstein by two percentage points, 51 to 49 percent. * denotes en estiméis ss of 3:45 AM Wilson’s road to victory was paved with a high Governor number of absentee ballots cast in his favor. Many Wilson I K E H of the mail-in votes were tabulated just after the Feinstein i polls closed, contributing to a 20-point lead the for mer San Diego mayor held early in die evening. Lt. Governor Feinstein suiged back through the night, and as McCarthy | See RESULTS, p.5 Bergeson U.S. Congress Lagomarsino mm IVRPD Race Over; Perez-Ferguson rrs LorenZ Not Avail Incumbents Tossed PROPOSITIONS From Local Office MARC SYVERTSEN/Daily Naxos By Jeanine Natale and Patrick Whalen I.V'. Suds & Duds Staff Writers______________________________ 128 - Big Green Isla Vista voters Tuesday chose newcomers Matt Dobberteen and Hal Kopeikin to sit on the board of The spirits were unleashed in | the highly politicized Isla Vista Recreation and 130 >\Forests I.V.