Dely Wildfire.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tango Buenos Aires La Cumparsita Matos Rodriguez the Company

CAL PERFORMANCES PRESENTS PROGRAM Friday, January 21, 2011, 8pm Fire and Passion of Tango Zellerbach Hall ACT I Tango Buenos Aires La Cumparsita Matos Rodriguez The Company Preparense Astor Piazzolla Cynthia Avila El Andariego Alfredo Gobbi Demián and Cynthia on the way to the salon. Demián García & Cynthia Avila Pavadita Oscar Herrero Demián and Cynthia arrive and they join the dance. At the salon, couples dance intimately. Cynthia sees Mauricio, the man she likes, arriving accompanied by another woman, Inés. The Company Melancólico Julian Plaza The Orchestra Nochero Soy Oscar Herrero The romantic couple. Maria Lujan Leopardi & Esteban Simon El Internado Francisco Canaro The indifferent couple. Florencia Blanco & Gonzalo Cuello CAMI La Luciérnaga O. Acosta, Adolfo Armando & Jose Dames The comic couple. Fire and Passion of Tango Florencia Mendez & Pedro Zamin Celos Jacob Gade The passionate couple. Inés Cuesta & Mauricio Celis Los Mareados Juan Carlos Cobian & Enrique Cadícamo Cynthia dances with the men at the salon to attract Mauricio’s attention. Cal Performances’ 2010–2011 season is sponsored by Wells Fargo. The Company A Palermo Antonio Podesta The Company 4 CAL PERFORMANCES CAL PERFORMANCES 5 PROGRAM CAST Tanguera Mariano Mores Tango Buenos Aires The Company General Director Rosario Bauza Art Production Lucrecia Laurel INTERMISSION Costume Design Miguel Iglesias Coordination & Photography Lucrecia Laurel ACT II Lighting Design Andres Mattiuada Bandoneón Solo Astor Piazzolla Choreographer Susana Rojo Demián García Dancers Milongueando -

Lista De Inscripciones Lista De Inscrições Entry List

LISTA DE INSCRIPCIONES La siguiente información, incluyendo los nombres específicos de las categorías, números de categorías y los números de votación, son confidenciales y propiedad de la Academia Latina de la Grabación. Esta información no podrá ser utilizada, divulgada, publicada o distribuída para ningún propósito. LISTA DE INSCRIÇÕES As sequintes informações, incluindo nomes específicos das categorias, o número de categorias e os números da votação, são confidenciais e direitos autorais pela Academia Latina de Gravação. Estas informações não podem ser utlizadas, divulgadas, publicadas ou distribuídas para qualquer finalidade. ENTRY LIST The following information, including specific category names, category numbers and balloting numbers, is confidential and proprietary information belonging to The Latin Recording Academy. Such information may not be used, disclosed, published or otherwise distributed for any purpose. REGLAS SOBRE LA SOLICITACION DE VOTOS Miembros de La Academia Latina de la Grabación, otros profesionales de la industria, y compañías disqueras no tienen prohibido promocionar sus lanzamientos durante la temporada de voto de los Latin GRAMMY®. Pero, a fin de proteger la integridad del proceso de votación y cuidar la información para ponerse en contacto con los Miembros, es crucial que las siguientes reglas sean entendidas y observadas. • La Academia Latina de la Grabación no divulga la información de contacto de sus Miembros. • Mientras comunicados de prensa y avisos del tipo “para su consideración” no están prohibidos, -

Song of the Year

General Field Page 1 of 15 Category 3 - Song Of The Year 015. AMAZING 031. AYO TECHNOLOGY Category 3 Seal, songwriter (Seal) N. Hills, Curtis Jackson, Timothy Song Of The Year 016. AMBITIONS Mosley & Justin Timberlake, A Songwriter(s) Award. A song is eligible if it was Rudy Roopchan, songwriter songwriters (50 Cent Featuring Justin first released or if it first achieved prominence (Sunchasers) Timberlake & Timbaland) during the Eligibility Year. (Artist names appear in parentheses.) Singles or Tracks only. 017. AMERICAN ANTHEM 032. BABY Angie Stone & Charles Tatum, 001. THE ACTRESS Gene Scheer, songwriter (Norah Jones) songwriters; Curtis Mayfield & K. Tiffany Petrossi, songwriter (Tiffany 018. AMNESIA Norton, songwriters (Angie Stone Petrossi) Brian Lapin, Mozella & Shelly Peiken, Featuring Betty Wright) 002. AFTER HOURS songwriters (Mozella) Dennis Bell, Julia Garrison, Kim 019. AND THE RAIN 033. BACK IN JUNE José Promis, songwriter (José Promis) Outerbridge & Victor Sanchez, Buck Aaron Thomas & Gary Wayne songwriters (Infinite Embrace Zaiontz, songwriters (Jokers Wild 034. BACK IN YOUR HEAD Featuring Casey Benjamin) Band) Sara Quin & Tegan Quin, songwriters (Tegan And Sara) 003. AFTER YOU 020. ANDUHYAUN Dick Wagner, songwriter (Wensday) Jimmy Lee Young, songwriter (Jimmy 035. BARTENDER Akon Thiam & T-Pain, songwriters 004. AGAIN & AGAIN Lee Young) (T-Pain Featuring Akon) Inara George & Greg Kurstin, 021. ANGEL songwriters (The Bird And The Bee) Chris Cartier, songwriter (Chris 036. BE GOOD OR BE GONE Fionn Regan, songwriter (Fionn 005. AIN'T NO TIME Cartier) Regan) Grace Potter, songwriter (Grace Potter 022. ANGEL & The Nocturnals) Chaka Khan & James Q. Wright, 037. BE GOOD TO ME Kara DioGuardi, Niclas Molinder & 006. -

Playbill 0911.Indd

umass fine arts center CENTER SERIES 2008–2009 1 2 3 4 playbill 1 Latin Fest featuring La India 09/20/08 2 Dave Pietro, Chakra Suite 10/03/08 3 Shakespeare & Company, Hamlet 10/08/08 4 Lura 10/09/08 DtCokeYoga8.5x11.qxp 5/17/07 11:30 AM Page 1 DC-07-M-3214 Yoga Class 8.5” x 11” YOGACLASS ©2007The Coca-Cola Company. Diet Coke and the Dynamic Ribbon are registered trademarks The of Coca-Cola Company. We’ve mastered the fine art of health care. Whether you need a family doctor or a physician specialist, in our region it’s Baystate Medical Practices that takes center stage in providing quality and excellence. From Greenfield to East Longmeadow, from young children to seniors, from coughs and colds to highly sophisticated surgery — we’ve got the talent and experience it takes to be the best. Visit us at www.baystatehealth.com/bmp Supporting The Community We Live In Helps Create a Better World For All Of Us Allen Davis, CFP® and The Davis Group Are Proud Supporters of the Fine Arts Center! The work we do with our clients enables them to share their assets with their families, loved ones, and the causes they support. But we also help clients share their growing knowledge and information about their financial position in useful and appropriate ways in order to empower and motivate those around them. Sharing is not limited to sharing material things; it’s also about sharing one’s personal and family legacy. It’s about passing along what matters most — during life, and after. -

Instructions

MY DETAILS My Name: Jong B. Mobile No.: 0917-5877-393 Movie Library Count: 8,600 Titles / Movies Total Capacity : 36 TB Updated as of: December 30, 2014 Email Add.: jongb61yahoo.com Website: www.jongb11.weebly.com Sulit Acct.: www.jongb11.olx.ph Location Add.: Bago Bantay, QC. (Near SM North, LRT Roosevelt/Munoz Station & Congressional Drive Capacity & Loadable/Free Space Table Drive Capacity Loadable Space Est. No. of Movies/Titles 320 Gig 298 Gig 35+ Movies 500 Gig 462 Gig 70+ Movies 1 TB 931 Gig 120+ Movies 1.5 TB 1,396 Gig 210+ Movies 2 TB 1,860 Gig 300+ Movies 3 TB 2,740 Gig 410+ Movies 4 TB 3,640 Gig 510+ Movies Note: 1. 1st Come 1st Serve Policy 2. Number of Movies/Titles may vary depends on your selections 3. SD = Standard definition Instructions: 1. Please observe the Drive Capacity & Loadable/Free Space Table above 2. Mark your preferred titles with letter "X" only on the first column 3. Please do not make any modification on the list. 3. If you're done with your selections please email to [email protected] together with the confirmaton of your order. 4. Pls. refer to my location map under Contact Us of my website YOUR MOVIE SELECTIONS SUMMARY Categories No. of titles/items Total File Size Selected (In Gig.) Movies (2013 & Older) 0 0 2014 0 0 3D 0 0 Animations 0 0 Cartoon 0 0 TV Series 0 0 Korean Drama 0 0 Documentaries 0 0 Concerts 0 0 Entertainment 0 0 Music Video 0 0 HD Music 0 0 Sports 0 0 Adult 0 0 Tagalog 0 0 Must not be over than OVERALL TOTAL 0 0 the Loadable Space Other details: 1. -

Spanish Karaoke DVD/VCD/CDG Catalog August, 2003

AceKaraoke.com 1-888-784-3384 Spanish Karaoke DVD/VCD/CDG Catalog August, 2003 Version) 03. Emanuel Ortega - A Escondidas Spanish DVD 04. Jaci Velasquez - De Creer En Ti 05. El Coyote Y Su Banda Tierra Santa - Sufro 06. Liml - Y Dale Fiesta Karaoke DVD Vol.1 07. Mana - Te Solte La Rienda ID: SYOKFK01SK $Price: 22 08. Marco Antonio Solis - El Peor De Mis Fracasos Fiesta Karaoke DVD Vol.1 09. Julio Preclado Y Su Banda Perla Del Pacifico - Me 01. Enrique Iglesias - Nunca?Te Ol Vidare Caiste Del?Cielo 02. Shakira - Inevitable 10. Limite - Acariciame 03. Luis Miguel - Dormir Contigo 11. Banda Maguey - Dos Gotas De Agua 04. Victor Manuelle?- Pero Dile 12. Milly Quezad - Pideme 05. Millie - De Hoy En Adelante 13. Diego Torres - Que Sera 06. Tonny Tun Tun - Cuando La Brisa Llega 14. La Puerta 07. Enrique Iglesias - Solo Me Importas Tu (Be With 15. Victor Manuelle - Como Duele You) 16. Micheal Stuart - Casi Perfecta 08. Azul Azul - La Bomba 09. Banda Manchos - En Toda La Chapa Fiesta Karaoke DVD Vol.4 10. Los Tigres Del Norie - De Paisano ID: SYOKFK04SK $Price: 22 11. Limite21 - Estas?Enamorada Fiesta Karaoke DVD Vol. 4 12. Intocahie - Ya Estoy Cansado 01. Ricky Martin - The Cup Of Life 13. Conjunto Primavera - Necesito Decirte 02. Chayanne - Dejaria Todo 14. El Coyote Y Su Banda Tierra Santa - No Puedo Ol 03. Tito Nie Ves - Le Gusta Que La Vean Vidar Tu Voz 04. El Poder Del North - A Ella 15. Joan Sebastian - Secreto De Amor 05. Victor Manuelle - Si La Ves 16. -

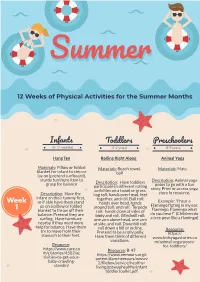

Infant Toddle Preschoole

SummeSumme 12 Weeks of Physical Activities for the Summer Months Infant Toddle Preschoole (0-12months) (1-2years) (3-5years) Hang Ten Rolling Right Along Animal Yoga Materials: Pillow or folded Materials: Beach towel, Materials: Mats blanket for infant to step or ball lay on (pretend surfboard), sturdy furniture item to Description: Animal yoga grasp for balance Description: Have toddlers participate in different rolling poses to go with a fun activities on a towel or grass. story. Print or access yoga Description: Have the Log roll: hands over head, feet story in resource. infant on their tummy first, together, and roll. Ball roll: Week or if able have them stand hands over head, hands Example: "I hear a 1 up on a pillow or folded around ball, and roll. Torpedo Flamingo fluting in my ear. blanket to throw off their roll: hands close at sides of Flamingo, Flamingo what balance. Pretend they are body and roll. Windmill roll: do you hear?" (Children do surfing . Have furniture one arm above head, one arm a tree pose like a flamingo) nearby if they need more at side, and roll. Downhill roll: help for balance. Have them roll down a hill or incline. Resource: try to move from their Pretend to be a rolly polly. stomach to their feet. https:// Have them think of different www.kidsyogastories.co variations. m/animal-yoga-poses- Resource: for-toddlers/ https://www.care.co Resource: B-47 m/c/stories/4582/ac https://www.nemours.org/c tivities-to-get-your- ontent/dam/nemours/wwwv baby-crawling- 2/filebox/service/healthy- standin/ living/growuphealthy/infant toddlertoolkit.pdf Toddle Preschoole Infant (1-2years) (3-5years) (0-12months) Wacky Walking Rain Storm Reaching Beyond Grasp Materials: Mud, sand, Materials: None Materials: Small smooth rocks, tubs of ball or squeaky water, wet foam pads, Description: Start by toy tape for line on the floor tapping fingers on the floor, then move to Description: Lay on the floor Description: Have the clapping on thighs, with the infant. -

Huecco U.S. Tour 2013 in PHILADELPHIA

MUSIC Huecco U.S. Tour 2013 in PHILADELPHIA Philadelphia Sun, July 14, 2013 9:00 pm Venue Underground Arts, 1200 Callowhill Street, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19107 View map More information Official website Spanish singer Hueco will be touring the East Coast this summer to present his new album Dame vida (Give me life). Huecco is a very particular artist who mixes rock, flamenco from his spanish roots and latin music. An in-your-face flavour cocktail of metal, punk, cha-cha, rumba flamenca, bolero and ska. A party to move the hips and mosh depending on each song. This special profile has made him play with artists so different like Sepultura or Bad Religion in a Festival and 2 weeks later open for Carlos Santana in Germany. Billboard said in 2009 that Huecco is to latin music what Gogol Bordello to balcanic music. Gold record in 2006 with his debut (40,000 albums sold), he also sold 280,000 ringtone downloads with his first single Pa’ mi guerrera with a style created by him called rumbatón, a medley o rumba and reggaeton produced by the Grammy winner KC Porter. In 2008, he wrote the anthem against the domestic violence, Se acabaron las lágrimas (Tears got over), which was Platinum Digital Album (45,000 ringtone downloads) and whose royalties he donated to the Fundación Mujeres in Spain. In 2011, he recorded the Dame vida album in L.A. produced by Grammy winner Thom Russo. He gathered an all-star for his Dame vida videoclip with soccer world champions Sergio Ramos and David Villa, and other players like the brazilian Daniel Alves (FC Barcelona), the argentinian Kun Agüero or the last european champions Thomas Müller and Philipp Lahm (Bayern Munich). -

DJ TOP 100 Charts International Woche 38 2012

Charts international Woche 38/2012 POS LW +/- KÜNSTLER / INTERPRET TITEL Label Punkte ^ Woche Bem. 01 - 0 TACABRO Tacatà Universal 9736 01 17 Ja 02 - 0 GUSTTAVO LIMA Balada (Tchê Tcherere Tchê Tchê) Universal 7286 02 15 Ja 03 - 0 AVICII Levels Zeitgeist / Universal 7160 01 40 Ja 04 - 0 DJ ANTOINE FEAT. THE BEAT SHAKERS Ma Chérie Kontor Records 6885 02 38 Ja 05 - 0 ASAF AVIDAN One day (Reckoning Song) Four Music 6816 02 16 Ja 06 - 0 OCEANA Endless Summer Ministry of Sound 6728 01 21 Ja 07 - 0 R.I.O. FEAT. U-JEAN Summer Jam Kontor Records 6422 02 7 Ja 08 - 0 MIKE CANDYS FEAT. EVELYN & PATRICK MILLER2012 (If The World Would End) Kontor 6118 01 26 Ja 09 - 0 R.I.O. FEAT. NICCO Party Shaker Kontor Records 5967 05 8 Ja 10 - SCOOTER 4 AM Sheffield Tunes / Kontor Records 5868 10 1 Ja 11 - 0 HIGH HEELERZ MEETS CLUBSTONE Superstar Neon Trax 5861 09 9 Ja 12 - 0 LYKKE LI I follow River Atlantic Records UK 5611 06 2 Nein 13 - 0 LOREEN Euphoria Warner Music Sweden AB 5580 13 2 Nein 14 - 0 GABRY PONTE FEAT. PITBULL & SOPHIA DEL CARMENBeat on my drum Columbia Dance 5507 08 6 Ja 15 - 0 MIKE CANDYS FEAT. SANDRA WILD Sunshine (Fly So High) Kontor Records 5456 15 8 Nein 16 - 0 JENNIFER LOPEZ FEAT. PITBULL Dance Again Sony Music 5332 15 20 Nein 17 - 0 LUCENZO FEAT. DON OMAR Danza Kuduro Universal 5291 01 52 Ja 18 - 0 GURU JOSH Infinity 2012 BigCityBeats Recordings 5167 05 18 Ja 19 - 0 ELENA Midnight Sun Sony Music 5071 19 18 Ja 20 - 0 JENNIFER LOPEZ FAET. -

The Slide Above Reads: “Our SPC Ethical Decision

1 2016-2021 Quality Enhancement Plan (QEP) Ethical Decision-Making (EDM) Tues 6 October 2020 Weekly Progress Report The slide above reads: “Our SPC Ethical Decision-making steps 1) Stop and think to determine the facts; 2) Identify options; 3) Consider consequences for yourself and others; 4) Make an ethical choice and take appropriate action.” and “Core Values of the Alamo Colleges: Students First; Respect for All; Community Engaged; Collaboration; Can-Do Spirit; Data-Informed” (Internal note: The statement above was added for Quality Matters (QM) and for Universal Design compliance.) EDM quote or tip slide, above for October 5: “The most valuable possession you can own is an open heart. The most powerful 1 2 weapon you can be is an instrument of peace.” Carlos Santana- Singer, Song Writer, ten-time-Grammy Award Winner https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carlos_Santana One of our four Ethical Decision-making steps highlighted in this quote: 3) Consider consequences for yourself and others. One of our six Core Values also highlighted: Respect for All. 1947: Santana was born in Mexico; learns to play violin at age five and guitar at age eight from his father, a mariachi musician. Family moves from Autlán to Tijuana, then to San Francisco, California. 1966: begins his musical career by forming the Santana Blues Band, embraces musical and spiritual inspiration and influences, support from and collaboration with: Ritchie Valens,Sly [Stone], Jimi Hendrix, the Stones, the Beatles, Tito Puente, Mongo Santamaría, Buddy Miles, Pharoah Sanders, Gregg Rolie, Michael Carabello, Michael Shrieve, David Brown, José "Chepito" Areas, Rob Thomas, B.B. -

Various 1, 2, 3, Let's Dance Mp3, Flac, Wma

Various 1, 2, 3, Let's Dance mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic / Latin / Pop Album: 1, 2, 3, Let's Dance Country: US Released: 2000 Style: Latin, House, Tribal House MP3 version RAR size: 1702 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1633 mb WMA version RAR size: 1101 mb Rating: 4.6 Votes: 807 Other Formats: AHX AUD DXD MOD AC3 APE MPC Tracklist Hide Credits Corazon (DJ Grego Pop Edit) 1 –Ricky Martin 3:55 Remix – DJ GregoSongwriter – KC Porter, Luis Angel Ojos Asi (Meme's 2001 Nights Long Mix) 2 –Shakira 6:00 Remix – DJ MemêSongwriter – Javier Garza, Pablo Flores, Shakira Pintame (Sugar's Tropical Spanglish) 3 –Elvis Crespo 4:11 Remix – DJ Sugar KidSongwriter – Elvis Crespo No Me Dejes De Querer ("Flores" Del Caribe Mix-Radio Edit) 4 –Gloria Estefan Remix – Pablo FloresSongwriter – Emilio Estefan, Jr., Gloria 4:29 Estefan, Robert Blades* Por Amarte (Remix) 5 –Enrique Iglesias 4:02 Songwriter – Enrique Iglesias, Roberto Morales Sobreviviré (The Groove Brothers Club Mix) 6 –Mónica Naranjo Remix – Brian Rawling, Graham StackSongwriter – Enrico Riccardi, 4:05 Luigi Albertelli Gotcha (Jazzy Jim Club Mix) 7 –DLG 3:33 Remix – Jazzy JimSongwriter – Manny Benito, Sergio George Come Baby Come (Club Remix) 8 –Gizelle*, Elvis Crespo 6:15 Remix – Lewis A. MartineéSongwriter – Elvis Crespo, Roberto Cora Salome 9 –Chayanne 4:14 Songwriter, Producer – Estéfano Asi (Pablo Flores Radio Edit) 10 –Jon Secada 4:04 Remix – Pablo Flores My Commanding Wife (110 Club Mix) 11 –Los Rabanes Remix – Gerald "Gee Gee" HarbourSongwriter – Boris Gardiner, 5:43 Emilio Regueira Pérez La Bomba (Diaz Brothers Remix) 12 –Azul Azul 4:52 Remix – Diaz Brothers Notes Some rare tracks on this compilation. -

Ricky Martin the Best of Ricky Martin Mp3, Flac, Wma

Ricky Martin The Best Of Ricky Martin mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic / Latin / Pop Album: The Best Of Ricky Martin Country: Asia Released: 2001 Style: Latin, Synth-pop MP3 version RAR size: 1235 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1404 mb WMA version RAR size: 1101 mb Rating: 4.7 Votes: 385 Other Formats: AAC MPC AU MOD AUD VOX FLAC Tracklist Hide Credits Livin' La Vida Loca 1 –Ricky Martin 4:03 Co-producer – Robi RosaProducer – Desmond Child Maria (Pablo Flores Spanglish Radio Edit) 2 –Ricky Martin Co-producer – Robi RosaProducer – KC PorterProducer 4:30 [Additional Production], Remix – Javier Garza, Pablo Flores She Bangs (English Version) 3 –Ricky Martin 4:40 Producer – Robi Rosa, Walter Afanasieff –Ricky Martin & Private Emotion 4 4:01 Meja Co-producer – Robi RosaProducer – Desmond Child Amor (New Remix By Salaam Remi) Producer – Emilio Estefan, Jr., Randy Barlow*, Robi 5 –Ricky Martin 3:25 RosaProducer [Remix], Remix – Salaam "The Chameleon" Remi* The Cup Of Life (La Copa De La Vida) [The Official Song Of 6 –Ricky Martin The World Cup, France '98] [Original English Version] 4:34 Producer – Desmond Child, Robi Rosa –Ricky Martin & Nobody Wants To Be Lonely 7 4:11 Christina Aguilera Producer – Walter Afanasieff Spanish Eyes/Lola, Lola (Music From "One Night Only" 8 –Ricky Martin Video) 5:44 Producer – Desmond Child, KC Porter, Robi Rosa She's All I Ever Had Co-producer – Robi RosaProducer – Emilio Estefan, Jr., 9 –Ricky Martin 4:55 George Noriega, Jon SecadaProducer [Additional Production] – Walter Afanasieff Come