December 2014 Update and Recommendations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

C O M M U N I Q

Fall 2018 C O M M U N I Q U É HAPPY AUTUMN The Board of Directors and staff at the Connecticut Alliance of Foster and Adoptive Families would like to wish you and your family a happy and healthy fall season! Support newly licensed families! Are you interested in being a BE A BUDDY Foster Parent? Training and stipend provided An Adoptive Parent? Want to know how you could Are you an experienced become a Kinship Family? Foster Parent? Call 1.888.KID-HERO Are you an experienced Relative Foster Parent? When you were newly In this Edition… Licensed, do you remember all the questions you had when your first foster child Executive Director’s Note…………….2 came into your home? Do you remember wondering what Orchards to visit this Fall……………...3 resources were available to you? Fall Halloween Fun…………………..4 Do you remember thinking, “If only I had Halloween Safety Checklist…………..5 another foster parent to talk to who has shared the same October Symposiums………………..6-7 experience?” Avenue of Dreams…………………..8 If you remember all of these times, then you might enjoy being a buddy! CAFAF Donations………………….9 Call Wendy Sander, Resources…………………………..10-12 Peer Network Coordinator at 1-800-861-8838 Legislative Update………………...13 Or email [email protected] Communiqué Fall 2018: A quarterly publication of the Connecticut Alliance of Foster and Adoptive Families, Inc. From the Desk of the Executive Director Board of Directors Welcome to autumn from CAFAF: Amy Kennedy Hopefully all enjoyed the President summer and fall will be calm and Cathy Gentile-Doyle colorful! Vice President CAFAF is proud to announce that over the summer we completed and Geralyn (Geri) Kogut compiled our first annual Post Secretary Licensing Training Preference survey. -

Wednesday, December 19, 2012

CONNECTICUT WEEKLY Connecticut Department of Agriculture Dannel P. Malloy, Governor Linda Piotrowicz, Editor Steven K. Reviczky, Commissioner Wednesday, December 19, 2012 NOTES from the DEPARTMENT FARMLAND RESTORATION PROGRAM NOW ACCEPTING APPLICATIONS FOR 2013 By Joseph Dippel, Acting Director, Bureau of Agricultural Development and Resource Preservation Governor Dannel P. Malloy and Agriculture Commissioner Ste- Installation of wildlife management fencing to protect crop ven K. Reviczky recently visited eastern Connecticut for a first-hand fields on FLRP area(s); look at farms participating in Governor Malloy’s new Farmland Res- Renovation of farm ponds, including farm pond manage- toration Program (FLRP). ment/irrigation and irrigation wells incidental to the re- Authorized under Governor Malloy’s 2011 jobs bill, the program stored cropland areas; encourages the reclamation of fallow farmland into productive crop- land. Funding in the amount of $5,000,000 was approved by the Restoration of shellfish beds or aquaculture ponds. Bond Commission for the new program in January. Under FLRP, farmers are eligible for matching grants of up to During the tour, Commissioner Reviczky pointed out, ―Not only $20,000 per project, on a 50% cost-sharing basis, to implement a does the program promote agriculture in the state, but it supports number of different restoration and conservation practices. jobs and a growing demand for local food.‖ A conservation plan or farmland restoration plan developed in The benefits of the FLRP are many. As agriculture in Con- consultation with the USDA Natural Resource Conservation Service necticut continues to grow, there is a need to push back the brush and Connecticut Conservation District specialists is required. -

H2a Statistics.Pdf

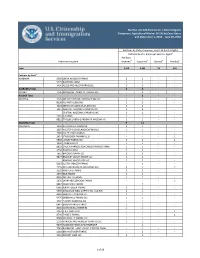

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services Petition for a Nonimmigrant Worker (I-129) with a Status of Temparary Agricultural Worker (H-2A) Receipts and Completions by Quarter by State by Company Fiscal Year 2012 State Company 1st Quarter State Company 2nd Quarter State Company 3rd Quarter State Company 4th Quarter Receipts Approvals Denials Receipts Approvals Denials Receipts Approvals Denials Receipts Approvals Denials ALABAMA 8 7 ALABAMA 7 7 0 ALABAMA 5 5 ALABAMA 4 3 BONNIE PLANT HALL 1 1 BECK S TURF INC 1 1 ALLEE & ALLEN FARMS 1 1 ALLEE & ALLEN FARMS 1 1 BONNIE PLANT JSC 1 1 MORRIS & MORRIS FARMS 1 1 JIMMY W DURBIN FARMS 1 1 BONNIE PLANTS ANDREWS 1 1 BONNIE PLANT OLD DIZ 1 1 MOSELEY S INTL INC 1 1 MOSELEY FARMS 2 2 BONNIE PLANTS STATION 33 1 BONNIE PLANTS INC 1 1 MULBERRY SOD FARM & PATTERSON FARM 1 1 MOSELEY S INTL INC 1 1 MOSELEY S INTL INC 1 1 JIMMY W DURBIN FARMS 1 1 PARSONS FARM 2 1 ALASKA 1 1 ARIZONA 4 3 1 SMITH PLANT FARM INC 1 1 SHORE ACRES PLANT FARM INC & ATKIN 1 1 MOSESIAN FARMS OF ALASKA INC 1 1 EAGLE PRODUCE LLC 1 1 STOKLEY NURSERY 1 1 YOUNG S PLANT FARM INC 1 ARIZONA 7 5 2 LA HACIENDA BUSINESS PARK 2 1 1 YOUNG S PLANT FARM INC 1 ALASKA 1 1 0 C&G SPRINKLER 1 1 SUN GARDEN FARMS 1 1 ARIZONA 3 3 MOSESIAN FARMS OF ALASKA INC 1 1 EAGLE PRODUCE LLC 3 3 ARKANSAS 5 5 1 IS MGMT LLC 1 1 ARIZONA 8 5 0 ISIDRO JUAREZ 1 1 DIXIE PLANTING CO INC 1 1 THE GROWERS CO INC 1 1 4B FARMS 1 1 MELBY CUSTOM CONTRACTING INC 1 1 HONEY LAND INC 1 1 UNION HARVEST 1 1 C&G SPRINKLER 1 SOUTH POTATO HARVESTING LLC 1 1 RANDY CLANTON FARMS INC 1 ARKANSAS -

NE IPM Center Partnership Proposal 2009

Partnership 2009 Rozyne Proposal Northeastern IPM Center – IPM Partnership Grants – 2009 – Proposal Project Description PD: Michael Rozyne Project Title: Meeting New Challenges, Meeting our Consumer 1. Project Category: Eco Apple IPM Working Group (IWG): 2. Project Summary Red Tomato, a non-profit organization, will continue to convene and coordinate an IPM Working Group including apple growers, agricultural scientists and extension agents, and its own in-house team of salespeople, communications manager, and art director. The close working relationship among growers, scientists, and marketers adds unusual depth and practicality to this project. The Eco Apple program has grown at a prodigious pace, from $400,000 in sales in 2005 to over $1.9 Million in 2008. But we need to balance this rapid growth with a strengthening of the Eco Apple IPM Protocol and the program itself, to sustain this growth over the long term. In this project, the Eco Apple IPM Working Group will build on the success of the Eco Apple program by strengthening its development of best practices – specifically, addressing the growing problem of internal Lepidoptera - and by strengthening its educational outreach to consumers. We propose to accomplish this latter goal by collecting and disseminating comparative pesticide use data of Eco vs. conventional apples, and by utilizing new technologies (including website blogs & videos, social networking, and DVDs) to reach consumers directly. We also propose to expand the program by pursuing relationships with Midwest growers, by researching value-added Eco Apple products, and researching extending this model to other crops. This program can continue to grow rapidly, even expanding to other regions and other fruits, but we must minimize the associated risks to ensure that this growth is sustainable. -

Orchards Can Add Their Imprint to 'New England Apples' Brochure

Volume XIV, No. 3 Spring 2010 McInt sh News The newsletter of the New England Apple Association Orchards can add their imprint to ‘New England Apples’ brochure he brochure/poster “New England Apples” is being revised this spring in a way that will enable member orchards to purchase quantities with their farm’s infor- Tmation on the back panel. Other changes to the brochure will include new recipes, some supplied by the region’s orchards, and new photographs of New England apple varieties on the poster side of the brochure. All member orchards will continue to receive a supply of brochures regardless of whether they select the option of having their information imprinted on the back panel, and the brochure Honeycrisp will continue to be distributed by the association at such events as the Eastern States Exposition. For those orchards that wish to order a supply with their im- print, the minimum order will be 1,000. The orchard information will be printed in green or black ink (to be determined), and can include a logo as well as the orchard’s name, location, phone and website address. Prices are as follows: Quantity Price Unit price 1,000 $300.00 $0.30 2,000 $500.00 $0.25 3,000 $600.00 $0.20 The deadline for ordering imprinted brochures is June 1. To order, send your information and a check for the ap- propriate amount (made out to “New England Apples”) to: Post Office Box 41, Hatfield, MA 01038. Spring 2010 McIntosh News 1 Orchard Run Russell Powell, executive director New England apples: a (re)introduction e work to promote New England apples in any way New England we can, supplementing the marketing efforts of Apple Association individual states and the New England state depart- Board of Directors Wments of agriculture. -

Winter 2015 Mcintosh News

Volume XIX, Number 3 WINTER 2014-2015 McInt sh News EDITION! THE NEW ENGLAND APPLE ASSOCIATION The new space has great potential, but it required took a huge step forward this fall with an significant renovations. There were major costs for new expanded presence at the Eastern States Exposition plumbing and electricity associated with the move. (“The Big E”). After several moves within the We were required to install a three-bay sink and a Massachusetts State Building over the past decade, separate hand-washing sink to bring the booth up to the Association hopes to have found a permanent Massachusetts code. The electrical work included fitting home in a space that has more working room, our commercial oven with a 60-amp receptacle. New England double the counter space, and additional light and Apple Association exposure compared to its previous location. Moving the heavy, bulky convection oven from old space to new took four people. The rest — freezer, Board of Directors Activity and sales at the apple booth have grown refrigerator, cider fountains, microwave, and the like — Ned O’Neill, chair J. P. Sullivan and Co., Ayer, Massachusetts every year since the Association had its first booth we moved ourselves. Mo Tougas, vice chair in 2003, and they reached an all-time high in 2012 Tougas Family Farm, Northborough, Massachusetts when a last-minute cancellation by a neighboring We had an existing shed demolished, painted the brick John Rogers, secretary-treasurer vendor enabled the Association to double its space at wall behind oven and sinks, and purchased existing Rogers Orchards, Southington, Connecticut its former site. -

A Record Year for Apple Pie Applefest and ‘Big E’ Serve up More Pies Than Ever

Volume XVII, No. 2 Winter 2013 A record year for apple pie AppleFest and ‘Big E’ serve up more pies than ever pages 4, 7 IFTA scholarships available The New England Apple Association is pleased to offer up to 20 $250 scholarships to help young farmers attend the 2013 International Fruit Tree Association (IFTA) Annual Conference and Intensive Workshop in New England Boston February 23 to March 1. The scholarships Apple Association are funded by a grant from Farm Credit Northeast AgEnhancement. Board of Directors Gordon Waterman, chair Romac Sales, Sanford, Maine The theme for the 2013 IFTA conference is «Technology,” and workshops and speakers will cover Mo Tougas, vice chair Tougas Family Farm, Northborough, Massachusetts such topics as varieties, mechanization, pest management, John Rogers, secretary-treasurer and information management, including sessions on Rogers Orchards, Southington, Connecticut orchard automation projects at Penn State, Carnegie Andrea Darrow Melon, and Washington State University, and planting Green Mountain Orchards, Putney, Vermont systems that will most easily be adapted to automation, Heather Faubert such as «Le Mur Fruitiere,» or «the fruiting wall,» which University of Rhode Island has been in development in France and Belgium for a Barney Hodges Jr. number of years. Sunrise Orchards, Middlebury, Vermont Ellen McAdam There will be an all-day intensive workshop on McDougal Orchards, Springvale, Maine pick-your-own marketing. Growers attending the IFTA Ned O’Neill J. P. Sullivan and Co., Ayer, Massachusetts conference will see new and innovative products, learn the latest research, and have outstanding opportunities for Chuck Souther Apple Hill Farm, Concord, New Hampshire networking outside the region. -

I-129 H2A Performance Data FY2016 Quarter 3

Number of I-129 Petition for a Nonimmigrant Temporary Agricultural Worker (H-2A) by Case Status and State, April 1, 2016 - June 30, 2016 Petitions by State, Company, and FEIN (Last 4 Digits) Petitions by U.S. Employer and U.S. Agent1 Petitions Petitioner Location Received2 Approved3 Denied4 Pending5 Total 3,118 3,593 23 643 Petitions by State6 ALABAMA 0909 LINDA MOSELEY FARMS 1 1 - - 5725 PARSONS FARM 1 1 - - 3490 ALLEE AND ALLEN FARMS LLC 1 1 - - ALABAMA Total 3 3 - - ALASKA 1726 MOSESIAN FARMS OF ALASKA INC - 1 - - ALASKA Total - 1 - - ARIZONA 7145 MELBY CUSTOM CONTRACTING INC 1 1 - - 8998 AG INSTALLERS INC 1 2 - - 7464 SERVICIOS AGRICOLAS MEX INC 1 1 - - 1311 CENTRAL ARIZONA FARMING INC 3 4 - - CENTRAL ARIZONAL FARMING INC 1 1 - - 2391 G FARMS 1 1 - - 8852 TAYLOR S HERB GARDEN OF ARIZONA IN 1 1 - - ARIZONA Total 9 11 - - ARKANSAS 1039 PATTSVILLE FARMS INC 1 1 - - 1587 HILLTOP SOD & LANDSCAPING LLC 1 1 - - 7580 CALEB JONES FARMS 1 1 - - 3614 STRACENER FARMING CO - - - 1 5968 LOWRY FARMS INC 3 2 - 1 1090 FARM H2A LLC 1 1 - - 8832 CHUCK HARROD DBA CHUCK HARROD FARM 1 1 - - 4760 RAMOS FARM 3 3 - - 7651 BRICKEYS GRAIN CO 1 1 - - 9877 BRADLEY LABOR GROUP LLC 1 1 - - BRADLEY LABOR GRP LLC 1 1 - - 5187 JUSTIN MENCER FARMS - 1 - - 2555 GILLAM FARMS OF ARKANSAS INC 3 1 - 2 3132 WHITEAIL FARMS 1 1 - - 2492 E&E FARMS 1 1 - - 8005 DOUBLE D FARMS 1 1 - - 2270 LARRY MCCLENDON FARMS - - - 1 9067 FOGLEMAN FARMS - 1 - - 0065 JERRY FULLER FARMS 1 1 - - 5393 ARKANSAS WELL SUPPLY INC / CAIN FI 1 1 - - 4666 WAKEFIELD PARTNERS 1 1 - - 5475 GREEN HILL FARMS -

State of Connecticut

STATE OF CONNECTICUT - SUMMARY OF EXPENDITURES For Fiscal Years 2005-2006 through 2009-2010 By Highest Paid Spending for 2005-2006 through 2009-2010 Totals $76.9 Billion! State Debt $72 Billion! Provided by The Federation of Connecticut Taxpayer Organizations The Federation extends our sincere appreciation to Robert Young our Secretary-Treasurer for obtaining and compiling the following information and Nancy Wyman who facilitated our information request as State Comptroller. The Federation continues to provide transparency in the spending of your tax dollars and will include state expenditures for Fiscal Year 2010-2011 when they become available. Susan Kniep, [email protected], 860-841-8032, http://ctact.org/; Robert Young, [email protected], Prepared Feb 4, 2011 LIST 1 OF 2 The following is Page One of the Original Report. Here we list those companies which received $10,000 and above. Please refer to Page 2 for those companies which received below $10,000. Totals include items from page 2. -

Number of I-129 Petition for a Nonimmigrant Temporary Agricultural Worker (H-2A) by Case Status and State, July 1 - September 30, 2013

Number of I-129 Petition for a Nonimmigrant Temporary Agricultural Worker (H-2A) by Case Status and State, July 1 - September 30, 2013 Petitions by State and Company Petitions by U.S. Employer and U.S. Agent1 Petitions Petitioner Location Received2 Approved3 Denied4 Pending5 Total 1,268 1,580 21 0 Petitions by State 6 Alabama 3 4 - - ALLEE AND ALLEN FARMS LLC - 1 - - BONNIE PLANTS 2 2 - - MOSELEY S INTL INC 1 1 - - Arizona 1 1 - - SILVER CANYON NURSERY DBA WHITFILL 1 1 - - Arkansas 5 8 - - ARKANSAS CROP TECHNOLOGIES INC 1 2 - - BATTURE CO 2 4 - - LOWRY FARMS INC 1 1 - - RIVER VALLEY HORT INC 1 1 - - California 13 17 - - ANGEL S CONTRACTING 1 1 - - BUOYE HONEY CO INC - 1 - - CF FARMING INC 1 2 - - FEDERICO BARAJAS LOPEZ DBA FL LABO 2 1 - - J&D HARVESTING INC 1 1 - - JOHN PODESTA FARMS 1 1 - - KFO INC 1 1 - - MD LABOR LLC 1 3 - - MIXTEPEC FARMING 1 2 - - SIERRA CASCADE NURSERY INC 2 2 - - WEST COAST TOMATO GROWERS LLC 2 2 - - Colorado 9 11 1 - CURTIS CHERRY RANCH 1 1 - - FLYING TRIANGLE RANCH 1 1 - - L AND M FARMS OF COLORADO LLC 1 1 - - LAZY 3X SHEEP CO LLC 2 3 - - MARC NEWMAN FARMS 1 2 - - MILK CREEK RANCH - - 1 - P&M LLC 1 2 - - STAR FARMS INC - 1 - - TWO BAR SHEEP CO LLC 1 - - - WELLSWEEP RANCHES 1 - - - Delaware 1 2 - - CANAM HARVESTING LLC 1 2 - - Florida 49 58 1 - B & W QUALITY GROWERS INC 7 8 - - Petitions by State and Company Petitions by U.S. Employer and U.S. -

Time to Hit the Orchard the Big E Is Coming Meet Mo Tougas

Volume XVI, No. 1 Fall 2011 Mc Time to hit the orchard It’s prime time for apple picking page 3 The Big E is coming (So is our 2012 calendar!) pages 9, 12 Meet Mo Tougas Apple Grower of the Year page 6 Bar Weeks Orchard Run Bar Weeks, executive director Taking in the big picture HE PACKAGE WAS WAITING ON THE KITCHEN TABLE when I walked in. My new camera. DSLR with a CMOS sensor, high-precision AF, all kinds of New England Tshooting modes, lots of megapixels. Two hours to charge the Apple Association battery. Thick manual. Board of Directors Memory card sold separately. Not the best day to go out Gordon Waterman, chair shooting apples anyway. Cloudy yesterday, rain in today’s Romac Sales, Sanford, Maine forecast. And Connecticut orchards are still recovering from Mo Tougas, vice chair Irene. Although it could have been much worse, southern Tougas Family Farm, Northborough, Massachusetts New England was hit pretty hard by the 60 mph winds. And, John Rogers, secretary-treasurer according to the U.S. National Hurricane Center, although Rogers Orchard, Southington, Connecticut they decreased to 50 mph by the time they entered northern Andrea Darrow New England, eight inches of rain were dropped on already Green Mountain Orchards, Putney, Vermont saturated Vermont. Barney Hodges Jr. Sunrise Orchards, Middlebury, Vermont In the midst of all this, power outages and all, I am taking on Ellen MacAdam the responsibility of executive director of the association. Russ McDougal Orchards, Springvale, Maine Powell, as many of you know, is branching out to write a book Ned O’Neill about the cultural history of apples in the United States (he J. -

New England Apples Partners with Juvenile Diabetes Foundation He New England Apple Association Has Agreed September 28: Cranbury Park, Norwalk, Conn

Volume XIII, No. 1 Fall 2008 McInt sh News The newsletter of the New England Apple Association New England apples partners with juvenile diabetes foundation he New England Apple Association has agreed September 28: Cranbury Park, Norwalk, Conn. to help promote a series of fundraising walks for Norton Brothers Fruit Farm donated 500 apples. the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation this September 28: Quinnipiac University, North Tfall in cities around New England. Member orchards are Haven, Conn., campus providing fresh apples to participants in the walks. Rogers Orchards and Lyman Orchards each donated Select orchards are donating apples to the events in 1,000 apples. their area, in exchange for free signage and other pro- October 5 McCooks Board Walk, Niantic, Conn. motional opportunities. Norton Brothers Fruit Farm donated 200 apples. Continued on next page Fall 2008 McIntosh News 1 ‘Big E’ again a promotional success Fresh, crisp apples, delicious cider, and mouth-watering cider doughnuts were among the apple products on sale at the New England Apple Association booth in the Massa- chusetts Building at the Eastern States Exposition (“The Big New England E”). The fair, which ran from September 12-28, is the largest Apple Association in New England. It drew more than one million visitors during its 17-day run, during the height of the fresh apple Board of Directors harvest. Gordon Waterman, chair The New England Apples booth featured items from a Romac Sales, Sanford, Maine number of Massachusetts orchards and businesses, includ- Mo Tougas, vice chair ing: Tougas Family Farm, Northborough, Massachusetts • Fresh apples from Atkins Farm in Amherst, Carl- John Rogers, secretary-treasurer in Harvard, in Rogers Orchard, Southington, Connecticut son Orchards Cold Spring Orchard Belchertown, and Dowse Orchards in Sherborn; Barney Hodges Jr.