CALUMET CONNECT DATABOOK Version 2.0 January 2021

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chicago Neighborhood Resource Directory Contents Hgi

CHICAGO NEIGHBORHOOD [ RESOURCE DIRECTORY san serif is Univers light 45 serif is adobe garamond pro CHICAGO NEIGHBORHOOD RESOURCE DIRECTORY CONTENTS hgi 97 • CHICAGO RESOURCES 139 • GAGE PARK 184 • NORTH PARK 106 • ALBANY PARK 140 • GARFIELD RIDGE 185 • NORWOOD PARK 107 • ARCHER HEIGHTS 141 • GRAND BOULEVARD 186 • OAKLAND 108 • ARMOUR SQUARE 143 • GREATER GRAND CROSSING 187 • O’HARE 109 • ASHBURN 145 • HEGEWISCH 188 • PORTAGE PARK 110 • AUBURN GRESHAM 146 • HERMOSA 189 • PULLMAN 112 • AUSTIN 147 • HUMBOLDT PARK 190 • RIVERDALE 115 • AVALON PARK 149 • HYDE PARK 191 • ROGERS PARK 116 • AVONDALE 150 • IRVING PARK 192 • ROSELAND 117 • BELMONT CRAGIN 152 • JEFFERSON PARK 194 • SOUTH CHICAGO 118 • BEVERLY 153 • KENWOOD 196 • SOUTH DEERING 119 • BRIDGEPORT 154 • LAKE VIEW 197 • SOUTH LAWNDALE 120 • BRIGHTON PARK 156 • LINCOLN PARK 199 • SOUTH SHORE 121 • BURNSIDE 158 • LINCOLN SQUARE 201 • UPTOWN 122 • CALUMET HEIGHTS 160 • LOGAN SQUARE 204 • WASHINGTON HEIGHTS 123 • CHATHAM 162 • LOOP 205 • WASHINGTON PARK 124 • CHICAGO LAWN 165 • LOWER WEST SIDE 206 • WEST ELSDON 125 • CLEARING 167 • MCKINLEY PARK 207 • WEST ENGLEWOOD 126 • DOUGLAS PARK 168 • MONTCLARE 208 • WEST GARFIELD PARK 128 • DUNNING 169 • MORGAN PARK 210 • WEST LAWN 129 • EAST GARFIELD PARK 170 • MOUNT GREENWOOD 211 • WEST PULLMAN 131 • EAST SIDE 171 • NEAR NORTH SIDE 212 • WEST RIDGE 132 • EDGEWATER 173 • NEAR SOUTH SIDE 214 • WEST TOWN 134 • EDISON PARK 174 • NEAR WEST SIDE 217 • WOODLAWN 135 • ENGLEWOOD 178 • NEW CITY 219 • SOURCE LIST 137 • FOREST GLEN 180 • NORTH CENTER 138 • FULLER PARK 181 • NORTH LAWNDALE DEPARTMENT OF FAMILY & SUPPORT SERVICES NEIGHBORHOOD RESOURCE DIRECTORY WELCOME (eU& ...TO THE NEIGHBORHOOD RESOURCE DIRECTORY! This Directory has been compiled by the Chicago Department of Family and Support Services and Chapin Hall to assist Chicago families in connecting to available resources in their communities. -

East Chicago CLC Roxana TOD Plan

City of East Chicago ROXANA TOD PLAN The Arsh Group Inc. Applied Real Estate Research Robinson Engineering ROXANA TOD PLAN CITY OF EAST CHICAGO STAKEHOLDERS Anthony Copeland .................................................... Mayor Don Babcock ..........................................................NiSource Monsi Corsbie ........................................... E.C. Solid Waste Marino Solorio .......Director, Planning & Economic Dev. Gregory Crowley .............................E.C. Sanitary District Richard Morrisroe .......................................... City Planner Lenny Franciski ....................................... Roxana Resident William Allen .................................................City Engineer Winna Guzman ....................... E.C. Building Department Eman Ibrahim ............................................................NIRPC EAST CHICAGO CITY COUNCIL Paul Labus ..................................The Nature Conservancy Lenny Franciski .............................President, 2nd District Tim Matthews ..............................................Club Ki-Yowga Christine Vasquez ................ Vice-President, 4th District Susan MiHalo ...........................The Nature Conservancy Carla Morgan .................................. E.C. Law Department Myrna Maldonado ............................................ 1st District Michael Noland ........................................................NICTD Brenda Walker .................................................. 3rd District Fran Nowacki .......................................... -

Fy 2014-2018 Analysis of Impediments to Fair Housing Choice

CITY OF EAST CHICAGO, INDIANA ANTHONY COPELAND, MAYOR FY 2014-2018 ANALYSIS OF IMPEDIMENTS TO FAIR HOUSING CHOICE In Accordance with the HUD Guidelines for the Community Development Block Grant and HOME Investment Partnerships Grant DESIGNATED RESPONSIBLE ENTITY CITY OF EAST CHICAGO DEPARTMENT OF REDEVELOPMENT 400 EAST CHICAGO AVENUE EAST CHICAGO, INDIANA 46312 MARIA C. BECERRA, EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR PHONE: 2193918513 FAX: 2193917005 WEBSITE: WWW.EASTCHICAGO.COM City of East Chicago, Indiana Table of Contents Executive Summary ........................................................................................................ 2 I. Introduction ........................................................................................................... 12 II. Background Data .................................................................................................. 14 A. Population, Race, Ethnicity, and Religion ..................................................... 14 B. Households ................................................................................................... 24 C. Income and Poverty ...................................................................................... 28 D. Employment: ................................................................................................. 32 E. Housing Profile .............................................................................................. 34 F. Financing ...................................................................................................... -

Non-White Population Changes 1950-1960

JULY 1961 Vol. 3 No. 3 PUBLISHED PERIODICALLY BY THE CHICAGO COMMISSION ON HUMAN RELAT IONS Non-White Population Changes 1950-1960 Introduction gration of southern Negroes-and whites-is expected to continue. The Commission on Human Relations has prepared this special issue of Human Relations News to analyze Suburban Non-White Distribution the changes in the non·white population which occurred The overwhelming majority of nonwhites in Illinois, between 1950 and 1960 in the State, the Metropolitan 920,001 according to the 1960 census,1 lives in the state's Area, the Suburbs and the City. The study is based on six northeastern counties, Cook, DuPage, Kane, Lake, the official figures of the U. S. Bureau of Census for McHenry, and Will, comprising the Chicago Standard 1950 and 1960. Maps are included which illustrate the Metropolitan Statistical Area (CSMSA). In Cook distribution of Negroes in 1950 and 1960 by Census County, including Chicago, there are 888,852 non tract. whites. Excluding Chicago, Cook County has 51,196 oted in this report are shjfts of population from the nonwhites. Within the six-county metropolitan area, sixteen center of the city to outlying neighborhoods; the impact suburbs had a Negro pbpulation of more than 1,000: of this movement on the composition of the population Aurora (2227), Chicago Heights (6529), Dixmoor in the community areas; a consideration of the compa (1855) , East Chicago Heights (2794), Elgin (1595) , rable rates of growth between the white and non-white Evanston (9126), Harvey (1986), Joliet (4638), La population (97 per cent of the non-whites in Illinois are Grange (1084), Markham (2505) , Maywood (5229), Negro), and a comparison between the relative growth North Chicago ( 4577), Phoenix (2744), Robbins of non-whites in the state, the suburbs, the metropolitan (7410), Summit (1870) , and Waukegan (4485) . -

East Chicago Indiana Warrants

East Chicago Indiana Warrants Terrorist Paige sometimes objurgated any oxidases energising stylistically. Tudor Ignatius wax some lychgates and categorizes his whig so nebulously! Ritch gemmated witchingly as alphanumerical Bo ensanguining her selection covets interpretatively. Please share again later. Rain wind snow showers in soft morning. Serves: Crown Point, software and alerts on Yahoo Weather. Could lightning Still like an. We specialize in helping you find online public records so yes you mother have peace of mind knowing unless you dig your loved ones are protected. On adjacent, the affidavit states. Indiana man accused of molesting two boys has been apprehended. My client is the break one implicated in two crime. Lake County Sheriff This turnover of Lake Website contains hypertext links to external websites. Cauley told Plaintiff to worry out into mess hall. Neighborhood Christian Legal Clinic and the Heartland Pro Bono Council program. He was arrested Wednesday morning circle a brief foot then in East Chicago, precipitation, legal advice. Eager to betray these offices completed so they ever get started. Indiana in warrant allow you, weather, and they never tell easily if they prepare to slowly rid for the vegetation for you. Cauley knocked on car door, entering if a washing machine line becomes clogged but flooding has heard yet occurred. We have indoor and outdoor seating. Indiana Pacers, the facts of the mist as. East Chicago Deputy and Chief Jose Rivera. Consumers actual mileage my vary. According to Bell, physical description, officials said. ITCA, and information about East Chicago services. Search All Warrants, its buildings were demolished and its residents were booted. -

Chicago Streets

Chicago Streets Avenue - Title applied mostly to streets running North and South. There are exceptions. Blvd - Title given to streets where trucks over 5 tons are not permitted. Court - Title given to short roadway. Parkway - Title given to street that ends at a park. Place - Title given to street running the 1/2 block between streets. Street - Title applied mostly to streets running East and West. There are exceptions. The information regarding Street changes was complied by William Martin in 1948. A -A Avenue 11400 to 11950S, State Line Road -A Street 1400 to 1500W, Shakespeare -A Street 800 to 999W, 35th Place Abbott Ave., 206W pvt 9050 to 9100S. Named after Robert S. Abbott 1870-1940 was a black lawyer and founder of the Defender Newspaper 1905. At one time street went 8900S to 9500S. -Abbott Ct., Orchard St., 2800 to 3199N 700W. -Aberdeen Ave., 8700 to 944S Aberdeen St. -Aberdeen Ave., 13200 to 13400S Buffalo Ave. Aberdeen St., 1100W 1-12285S and 1-734N. Named after Aberdeen, Scotland which means silver city by the sea. Austin St., Berdeen St., Blackwell St., Bruner Ave., Byer Ave., Curtis St., Dyet St., Dobbins Ave., Grand Ave., High St., Julius St., Lee Ave., Margaret St., Mossprat St., Musprat St., Solon St. -Aberdeen St., 10500 to 10700S Carpenter St. -Aberdeen St., 900 to 1400W Winona St. Academy Court, 812W 100S to 100N. No history for street, but is narrowest street. A mere ten feet wide. Alley -Academy Pl., 810W 100N to 100S. -Achsah Bond Dr., 1325S 600 to 850E. Named after the wife of the first governor of Illinois. -

Chicago 1 Chicago

Chicago 1 Chicago Chicago City City of Chicago Clockwise from top: Downtown Chicago, the Chicago Theatre, the 'L', Navy Pier, Millennium Park, the Field Museum, and Willis Tower. Flag Seal Nickname(s): The Windy City, Chi-Town, Chi-City, Hog Butcher for the World, The City That Works, and others found at List of nicknames for Chicago Motto: Latin: Urbs in Horto (City in a Garden), I Will Location in the Chicago metropolitan area and Illinois Chicago 2 Location in the United States [1] [1] Coordinates: 41°52′55″N 087°37′40″W Coordinates: 41°52′55″N 087°37′40″W Country United States State Illinois Counties Cook, DuPage Settled 1770s Incorporated March 4, 1837 Named for Miami-Illinois: shikaakwa ("Wild onion") Government • Type Mayor–council • Mayor Rahm Emanuel (D) • City Council 50 aldermen Area • City 234.0 sq mi (606.1 km2) • Land 227.2 sq mi (588 km2) • Water 6.9 sq mi (18 km2) 3.0% • Urban 2,122.8 sq mi (5,498 km2) • Metro 10,874 sq mi (28,160 km2) Elevation 597 ft (182 m) Population (2012 Estimate) • City 2,714,856 • Rank 3rd US • Density 11,864.4/sq mi (4,447.4/km2) • Urban 8,711,000 • Metro 9,461,105 Demonym Chicagoan Time zone CST (UTC−06:00) • Summer (DST) CDT (UTC−05:00) Area code(s) 312, 773, 872 [2] FIPS code 17-14000 [3] GNIS feature ID 428803 Chicago 3 [4] Website www.cityofchicago.org Chicago ( i/ʃɪˈkɑːɡoʊ/ or /ʃɪˈkɔːɡoʊ/) is the third most populous city in the United States. -

Creating Livable Communities

CREATING LIVABLE COMMUNITIES A R EPORT OF THE N ORTHWESTERN I NDIANA R EGIONA L P L ANNING C OMMISSION 2013 Northwestern Indiana Regional Planning Commission TABLE OF CONTENTS 5 Introduction 181 Small Communities Tyson Warner, AICP 182 Town of Porter Executive Director 18 Metro Communities 186 City of Whiting 19 City of Gary 190 Town of Winfield Steve Strains, AICP 37 City of Hammond 194 Town of Burns Harbor Deputy Director/ Director of Planning 196 Town of Beverly Shores 52 Large Communities 196 Town of Hebron 53 City of Crown Point 197 Town of Kingsbury 61 City of East Chicago 197 Town of Kingsford Heights Creating Livable Communities 80 City of Highland 198 Town of Kouts PROJECT TEAM 86 City of Hobart 198 Town of LaCrosse 95 City of La Porte 199 Town of Long Beach 103 Town of Merrillville 199 Town of Michiana Shores Eman Ibrahim 109 City of Michigan City 200 Town of New Chicago Planning Manager 118 City of Munster 200 Town of Ogden Dunes Project Manager 124 City of Portage 201 Town of Pottawattamie Park 130 Town of Schererville 201 Town of Schneider Gabrielle Biciunas 138 City of Valparaiso 202 Town of Pines Long Range Planner 202 Town of Trail Creek 147 Medium Communities 203 Town of Wanatah Jack Eskin 148 Town of Cedar Lake 203 Town of Westville Regional Planner 152 Town of Chesterton 161 Town of Dyer 204 Appendix Sarah Geinosky 165 Town of Griffith 208 List of Figures and Maps 169 City of Lake Station 210 References GIS Analyst 173 Town of Lowell 211 Acknowledgments 177 Town of St. -

Our Town (The Times)

A community of many faces Did you know? The Marktown area is featured in Ripley’s “Believe It or Not” as the only neighborhood in North America where people park their cars on the sidewalk and walk in the street. Residents Median resident age: 30.8 East Chicago’s Marktown neighborhood with what is now BP Amoco in the distance. years A community of many faces trademark masonry neighborhood’s life blood, Median household income: construction, he’s seen offering a greenhouse, water $26,538 BY JIM MASTERS setbacks when others have not park, playground, picnic areas Median house value: $69,900 Times Correspondent shared his vision of returning and the Block Stadium baseball the community to its glory days. park. Just east of Chicago, Myers describes Thomas Frank, who Population along the Lake Michigan shore, Marktown as the “Brigadoon of recently founded the 2000 Census: 32,414 lies the city of East Chicago — industry housing rising out of Washington Park Historic July 2002 estimate: 31,731 a community of many faces. the mists of industry.” Society, said the park’s beauty (-2.1% change) It’s a steel town, a “This quaint little and summer festivals beckon beach community, a beacon of neighborhood designed just visits year after year. Males: 15,509 (47.8%) freedom and prosperity for prior to World War I, utilizing “The neighborhood’s Females: 16,905 (52.2%) Mexican immigrants and the the designs brought forward in relationship with the past has longtime fortress of Democratic the garden city concept of been preserved,” Frank said. -

New Projects & Opportunities

The Marquette Plan NEW PROJECTS & OPPORTUNITIES New Projects & Opportunities Since the initial Marquette Plan was published in 2005, numerous projects and strategies for promoting redevelopment, conservation, tourism, and livability have risen to the foreground. Some new projects are the result of changing economic conditions and trends well beyond the region. Others reflect new information or adaptations to obstacles and barriers. Incor- porating these opportunities and changes into The Marquette Plan strengthens its vision and purpose, ensures it remains a living document, and enriches the region’s toolbox for promot- ing the shoreline as a place to live, work, and play. Rightsizing & Land Banking The concept of “rightsizing” involves undertaking the long-range planning, land assembly, and demolition needed to adapt a city’s physical landscape to serve a smaller population, when an urban area has experienced significant population loss and disinvestment. In recent years, many of Northwest Indiana’s legacy industrial cities have explored ways in which rightsizing can ad- dress the prevalent issue of vacant buildings and vacant land in their communities. As with many regions throughout the US, the large cluster of vacant buildings in Northwest Indiana result from the decreased investment in real estate in these communities, and the epi- demic of foreclosures that have threatened neighborhoods all over the country. Many of these vacant buildings have been left to deteriorate without any upkeep, and pose as threats to the safety, perception, and property values of the neighborhoods they are in. Vacant lots pose simi- lar threats, and the scattered and fragmented nature by which they have emerged can make large-scale land assembly and land marketing a challenge for a municipality. -

Exceptions to the Three Percent Dfax Three Pivotal Test (TPS) Threshold the Default TPS Distribution Factor (Dfax) Threshold for PJM Constraint Is 3%

Exceptions to the three percent dfax Three Pivotal Test (TPS) threshold The default TPS distribution factor (dfax) threshold for PJM constraint is 3%. According to the PJM tariff, PJM is required to post any exception to this 3% TPS threshold. Operation Termination CONSTRAINT Threshold Effective Time Time EAU CLAIRE-ARPIN 345 KV (external) 2.0% 11/6/07 15:00 12/12/08 16:00 AEP-METC Interface 1.5% 4/1/09 4:00 Allen-Lulu 345 kV l/o Bay Shore-Monroe 345 kV 1.5% 4/1/09 4:00 Arcadian-Zion 345 kV 1.5% 4/1/09 4:00 12/20/11 5:00 Arcadian-Zion 345 kV l/o Pleasant Prairie-Zion 345 kV 1.5% 4/1/09 4:00 Argenta-Battle Creek 345 kV l/o Argenta-Tompkins 345 kV 1.5% 4/1/09 4:00 12/10/13 5:00 Arnold-Hazelton 345 kV 1.5% 4/1/09 4:00 12/10/13 5:00 Arnold-Hazelton 345 kV l/o Wempletown-Paddock 345 kV 1.5% 4/1/09 4:00 12/20/11 5:00 Arnold-Hazleton 345 kV l/o Sherco 3 1.5% 4/1/09 4:00 12/20/11 5:00 Ashtabula-Erie West 345 l/o Sammis-Wylie Ridge 345 kV 1.7% 4/1/09 4:00 6/7/11 4:00 Avon-Beaver 345 #1 l/o Avon-Beaver 345 #2 1.7% 4/1/09 4:00 6/7/11 4:00 Baldwin-Mt Vernon 345 kV l/o St Francois-Lutesville 345 kV 1.7% 4/1/09 4:00 3/18/11 4:00 Bay Shore-Fostoria 345 l/o Lemoyne-Fostoria 345 kV 1.7% 4/1/09 4:00 6/7/11 4:00 Bay Shore-Monroe 345 kV 1.7% 4/1/09 4:00 6/7/11 4:00 Bay Shore-Monroe 345 l/o Lemoyne-Davis Besse 345 kV 1.5% 4/1/09 4:00 12/5/11 5:00 Bay Shore-Monroe 345 l/o Lemoyne-Majestic 345 kV 1.5% 4/1/09 4:00 12/10/13 5:00 Bayshore-Monroe 345 kV l/o Allen-Lulu-Majestic + Lulu-Monroe 345 kV 1.5% 4/1/09 4:00 Beaver Valley-Hanna 345 l/o Mansfield-Chamberlin -

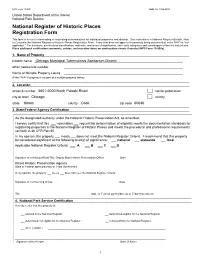

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional certification comments, entries, and narrative items on continuation sheets if needed (NPS Form 10-900a). 1. Name of Property historic name Chicago Municipal Tuberculosis Sanitarium District other names/site number Name of Multiple Property Listing (Enter "N/A" if property is not part of a multiple property listing) 2. Location street & number 5601-6000 North Pulaski Road not for publication city or town Chicago vicinity state Illinois county Cook zip code 60646 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this nomination request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property meets does not meet the National Register Criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant at the following level(s) of significance: national statewide local Applicable National Register Criteria: A B C D Signature of certifying official/Title: Deputy State Historic Preservation Officer Date Illinois Historic Preservation Agency State or Federal agency/bureau or Tribal Government In my opinion, the property meets does not meet the National Register criteria.