Queensland Music Festival's Help Is on Its Wayproject

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Some Kind of Wonderful.” Sponsored By: WLDE and ABC Us Alive”

REO Speedwagon Free Concerts Wednesday, September 26, 8 p.m. Fort Wayne Philharmonic Youth Symphony Founding member Neal Doughty and & Youth Concert Orchestra Kevin Cronin bring this Champaign, Sunday, May 20, 2 p.m. IN 46805 Wayne, Fort Blvd. 705 E. State Ill originated boy band back to the Midwest. They’ll play their The Foellinger Theatre is proud to bring back these local groups biggest hits “Keep on Lovin’ You,” “Time for me to Fly,” and many for an afternoon of spectacular musical entertainment. Some Kind of more of your favorites from their 40 million albums sold. Presented by Pacific Coast Concerts. Tickets: $60-$100, Fort Wayne Area Community Band $6 ticket fee Tuesday, June 12, 7:30 p.m. The Community Band will be joined by area band students in grades Wonderful 8-12 as they present “Side By Side,” a concert of All-American band music. Tickets Old Crown Brass Bandh Tuesday, June 19, 7:30 p.m. Old Crown Brass Band is an all-volunteer band that is modeled On-line By Phone after traditional British brass bands. The group is based in Fort www.foellingertheatre.org (260) 427-6000 Wayne and composed of a diverse group of professionals and very talented, dedicated amateur musicians. The band is under In Person the direction of T. J. Faur and Tony Alessandrini. Fort Wayne Parks & Recreation Department 705 E. State Blvd., Fort Wayne, IN 46805 Fort Wayne Area Community Band Monday-Friday, 8:00 a.m.-5:00 p.m. Tuesday, July 10, 7:30 p.m. The Fort Wayne Area Community Band presents “A Really Big Show” featuring music from the best and biggest movies and Foellinger Theatre Broadway shows. -

Single Event Tickets on Sale August 26 at 10 Am

Troy Andrews has been hailed as New Orleans’ brightest star in a generation. The Purple Xperience is widely considered the greatest Prince tribute act Having grown up in a musical family, Andrews came by his nickname, around. The five-piece group, led by Marshall Charloff, “embodies the image, Sept 20 Trombone Shorty, when his parents encouraged him to play trombone at age intensity and sounds” (musicinminnesota.com) of Prince’s life. Founded in Sept 30 Friday, 7:30 p.m. four. By the time he was eight, he was leading his own band in parades, halls 2011 by Charloff and original Revolution band member Matt “Doctor” Fink, Monday, 7:30 p.m. and even bars. He toured abroad with the Neville Brothers when he was still the Purple Xperience has entertained well over 300,000 fans, sharing stages in his teens and joined Lenny Kravitz’ band fresh out of high school – the New with The Time, Cameo, Fetty Wap, Gin Blossoms, Atlanta Rhythm Section Orleans Center for Creative Arts. His latest album, “Parking Lot Symphony,” and Cheap Trick. Charloff, who has performed nationwide fronting world-class captures the spirit and essence of The Big Easy while redefining its sound. symphonies, styles the magic of Prince’s talent in appearance, vocal imitation “Parking Lot Symphony” contains multitudes of sound – from brass band blare and multi-instrumental capacity. Charloff, playing keyboards and bass guitar, and deep-groove funk, to bluesy beauty and hip-hop/pop swagger – combined recorded with Prince on “94 East.” Alternative Revolt calls the resemblance with plenty of emotion, all anchored by stellar playing and the idea that, even between Charloff and Prince “striking … both in looks and musical prowess. -

January Spotlight February Spotlight Fat Tuesday

JANUARY SPOTLIGHT JANUARY 10 WHOSE LIVE ANYWAY? 11 PINK FLOYD LASER SPECTACULAR 12 ELVIS BIRTHDAY BASH 13 FRANKIE VALLI & THE FOUR SEASONS JAN 10 JAN 11 JAN 12 JAN 13 18 MASTERS OF ILLUSION WHOSE LIVE ANYWAY? PINK FLOYD ELVIS BIRTHDAY BASH FRANKIE VALLI & 19 THE STOMPDOWN featuring Drew Carey LASER SPECTACULAR Two of the world’s top Elvis THE FOUR SEASONS with Greg Proops, Jeff B. Davis and Joel Murray ERTH’S PREHISTORIC Packed with hits like “Hey You,” “Time,” entertainers, Mike Albert and Scot The original Jersey boy Frankie Valli 20 In this night of unforgettable interactive comedy, Drew Carey, Greg Proops, “Wish You Were Here,” “Comfortably Bruce, along with the Big E Band and his band are known for their AQUARIUM Jeff B. Davis and Joel Murray perform games and skits made famous on the Numb” and more, Pink Floyd Laser return to celebrate Elvis’ 84th blockbuster hits “Big Girls Don’t Emmy-nominated TV show Whose Line Is It Anyway? Audience participation Spectacular uses cutting-edge effects, birthday! Cry,” “Walk Like A Man,” “Can’t Take 22 DISNEY’S DCAPPELLA is the key to the show, so bring your suggestions because you might be high-powered lasers, video projection 7:00pm My Eyes Off You,” “Rag Doll,” “Who asked to join the cast onstage. and special lighting effects. 23 ARLO GUTHRIE 8:00pm 8:00pm Loves You” and so many more. 7:00pm 25 DRIVE-BY TRUCKERS LUCINDA WILLIAMS 26 JEANNE ROBERTSON 27 SARA EVANS 28 PINK MARTINI ADVENTURE FEBRUARY JAN 18 JAN 20 JAN 22 JAN 23 2 SINBAD THEATREWORKS: HENRY MASTERS OF ILLUSION ERTH’S PREHISTORIC AQUARIUM DISNEY’S DCAPPELLA ARLO GUTHRIE 4 ALICE’S RESTAURANT AND MUDGE Based on the award-winning CW Network The creators of Erth’s Dinosaur Zoo Live take your family on a new adventure Debuting on ABC’s American Idol, and series, and starring the world’s greatest recently releasing their first single, To celebrate the 50th Anniversary of CHALK the feature filmAlice’s Restaurant, folk award-winning magicians, this magic show to the bottom of the ocean. -

Harvest Records Discography

Harvest Records Discography Capitol 100 series SKAO 314 - Quatermass - QUATERMASS [1970] Entropy/Black Sheep Of The Family/Post War Saturday Echo/Good Lord Knows/Up On The Ground//Gemini/Make Up Your Mind/Laughin’ Tackle/Entropy (Reprise) SKAO 351 - Horizons - The GREATEST SHOW ON EARTH [1970] Again And Again/Angelina/Day Of The Lady/Horizons/I Fought For Love/Real Cool World/Skylight Man/Sunflower Morning [*] ST 370 - Anthems In Eden - SHIRLEY & DOROTHY COLLINS [1969] Awakening-Whitesun Dance/Beginning/Bonny Cuckoo/Ca’ The Yowes/Courtship-Wedding Song/Denying- Blacksmith/Dream-Lowlands/Foresaking-Our Captain Cried/Gathering Rushes In The Month Of May/God Dog/Gower Wassail/Leavetaking-Pleasant And Delightful/Meeting-Searching For Lambs/Nellie/New Beginning-Staines Morris/Ramble Away [*] ST 371 - Wasa Wasa - The EDGAR BROUGHTON BAND [1969] Death Of An Electric Citizen/American Body Soldier/Why Can’t Somebody Love You/Neptune/Evil//Crying/Love In The Rain/Dawn Crept Away ST 376 - Alchemy - THIRD EAR BAND [1969] Area Three/Dragon Lines/Druid One/Egyptian Book Of The Dead/Ghetto Raga/Lark Rise/Mosaic/Stone Circle [*] SKAO 382 - Atom Heart Mother - The PINK FLOYD [1970] Atom Heart Mother Suite (Father’s Shout-Breast Milky-Mother Fore-Funky Dung-Mind Your Throats Please- Remergence)//If/Summer ’68/Fat Old Sun/Alan’s Psychedelic Breakfast (Rise And Shine-Sunny Side Up- Morning Glory) SKAO 387 - Panama Limited Jug Band - PANAMA LIMITED JUG BAND [1969] Canned Heat/Cocaine Habit/Don’t You Ease Me In/Going To Germany/Railroad/Rich Girl/Sundown/38 -

4KQ's Australia Day

4KQ's Australia Day A FOOL IN LOVE JEFF ST JOHN A LITTLE RAY OF SUNSHINE AXIOM A MATTER OF TIME RAILROAD GIN ALL MY FRIENDS ARE GETTING MARRIED SKYHOOKS ALL OUT OF LOVE AIR SUPPLY ALL THE GOOD THINGS CAROL LLOYD BAND AM I EVER GONNA SEE YOUR FACE AGAIN THE ANGELS APRIL SUN IN CUBA DRAGON ARE YOU OLD ENOUGH DRAGON ARKANSAW GRASS AXIOM AS THE DAYS GO BY DARYL BRAITHWAITE BABY WITHOUT YOU JOHN FARNHAM/ALLISON DURBAN BANKS OF THE OHIO OLIVIA NEWTON-JOHN BE GOOD JOHNNY MEN AT WORK BECAUSE I LOVE YOU MASTER'S APPRENTICES BIG TIME OPERATOR THE ID/JEFF ST JOHN BLACK EYED BRUISER STEVIE WRIGHT BODY AND SOUL JO KENNEDY BOM BOM DADDY COOL BOOM SHA LA-LA-LO HANS POULSEN BOPPIN THE BLUES BLACKFEATHER CASSANDRA SHERBET CHAIN REACTION JOHN FARNHAM CHEAP WINE COLD CHISEL CIAO BABY LYNNE RANDELL COME AROUND MENTAL AS ANYTHING COME BACK AGAIN DADDY COOL COME SAID THE BOY MONDO ROCK COMMON GROUND GOANNA COOL WORLD MONDO ROCK CRAZY ICEHOUSE CURIOSITY (KILLED THE CAT) LITTLE RIVER BAND DARKTOWN STRUTTERS BALL TED MULRY GANG DEEP WATER RICHARD CLAPTON DO WHAT YOU DO AIR SUPPLY DON'T FALL IN LOVE FERRETS DON'T YOU KNOW YOU'RE CHANGING BILLY THORPE/AZTECS DOWN AMONG THE DEAD MEN FLASH & THE PAN DOWN IN THE LUCKY CO RICHARD CLAPTON DOWN ON THE BORDER LITTLE RIVER BAND DOWN UNDER MEN AT WORK DOWNHEARTED JOHN FARNHAM EAGLE ROCK DADDY COOL EGO (IS NOT A DIRTY WORD) SKYHOOKS ELECTRIC BLUE ICEHOUSE ELEVATOR DRIVER MASTER'S APPRENTICES EMOTION SAMANTHA SANG EVIE (PART 1, 2 & 3) STEVIE WRIGHT FIVE .10 MAN MASTER'S APPRENTICES FLAME TREES COLD CHISEL FORTUNE TELLER THE -

00003-26-2010 ( Pdf )

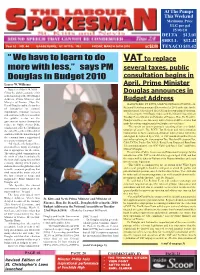

At The Pumps This Weekend Maximum Price ULG per gal 25/03/10 DELTA $13.01 SHELL $12.42 Year 52 NO. 44BASSETERRE, ST. KITTS, W.I. FRIDAY, MARCH 26TH 2010 EC$2.00 TEXACO $11.42 “ We have to learn to do VAT to replace more with less,” says PM several taxes, public Douglas in Budget 2010 consultation begins in Lesroy W. Williams April, Prime Minister Basseterre (March 24, 2010)— Citing the global economic crisis Douglas announces in as the backdrop in the 2010 Budget Address, Prime Minister and Budget Address Minister of Finance, Hon. Dr. Denzil Douglas outlined a number BASSETERRE, ST. KITTS, MARCH 23RD 2010 (CUOPM) – St. of initiatives to control Kitts and Nevis has announced November 1st 2010 as the date for the expenditure, eliminate excesses introduction of Value Added Tax (VAT) in the twin-island Federation. and eradicate inefficiencies within Delivering the 2010 Budget Address in the National Assembly on the public sector as the Tuesday, Prime Minister and Minister of Finance, Hon. Dr. Denzil L. government moves forward to Douglas said there are too many indirect taxes at different rates that reduce the Public Sector Debt, make the system complex and it will replace several taxes. which stood at EC $2.54 billion at “The current tax system promotes cascading of taxes or double the end of December 2008 while it taxation of goods. The ECCU Tax Reform and Administration continues with the transitioning of Commission in fact recommended that all indirect taxes within the the economy from a sugar-based sub-region be replaced by a VAT. -

Music Business and the Experience Economy the Australasian Case Music Business and the Experience Economy

Peter Tschmuck Philip L. Pearce Steven Campbell Editors Music Business and the Experience Economy The Australasian Case Music Business and the Experience Economy . Peter Tschmuck • Philip L. Pearce • Steven Campbell Editors Music Business and the Experience Economy The Australasian Case Editors Peter Tschmuck Philip L. Pearce Institute for Cultural Management and School of Business Cultural Studies James Cook University Townsville University of Music and Townsville, Queensland Performing Arts Vienna Australia Vienna, Austria Steven Campbell School of Creative Arts James Cook University Townsville Townsville, Queensland Australia ISBN 978-3-642-27897-6 ISBN 978-3-642-27898-3 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-3-642-27898-3 Springer Heidelberg New York Dordrecht London Library of Congress Control Number: 2013936544 # Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2013 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. Exempted from this legal reservation are brief excerpts in connection with reviews or scholarly analysis or material supplied specifically for the purpose of being entered and executed on a computer system, for exclusive use by the purchaser of the work. Duplication of this publication or parts thereof is permitted only under the provisions of the Copyright Law of the Publisher’s location, in its current version, and permission for use must always be obtained from Springer. -

Sizzling 70'S Printable List

Sizzling 70’s Printable List SHE'S IN LOVE WITH YOU SUZI QUATRO BEST OF MY LOVE EAGLES WHERE YOU LEAD BARBARA STREISAND SAY YOU LOVE ME FLEETWOOD MAC SHINING STAR EARTH WIND & FIRE MIND GAMES JOHN LENNON LOVE'S THEME LOVE UNLIMITED GIRLS ON THE AVENUE RICHARD CLAPTON SOFT DELIGHTS NEW DREAM CRACKLIN' ROSIE NEIL DIAMOND AIN'T GONNA BUMP NO MORE (WITH NO BIG FAT WOMAN) JOE TEX BECAUSE I LOVE YOU MASTER'S APPRENTICES RIDE A WHITE SWAN T REX PRECIOUS LOVE BOB WELCH PRELUDE/ANGRY YOUNG MAN BILLY JOEL STAYIN' ALIVE BEE GEES EVERYBODY PLAYS THE FOOL MAIN INGREDIENT ROCK AND ROLL ALL NITE KISS NA NA HEY HEY KISS HIM GOODBYE STEAM GOODBYE STRANGER SUPERTRAMP NEVER CAN SAY GOODBYE GLORIA GAYNOR GOODBYE TO LOVE CARPENTERS BABY IT'S YOU PROMISES (YOU GOTTA WALK) DON'T LOOK BACK PETER TOSH SATURDAY NIGHT BAY CITY ROLLERS SATURDAY NIGHTS ALRIGHT FOR FIGHTING ELTON JOHN ANOTHER SATURDAY NIGHT CAT STEVENS DANCIN' (ON A SATURDAY NIGHT) BARRY BLUE TUMBLING DICE ROLLING STONES SHAKE YOUR BOOTY K.C. & SUNSHINE BAND COZ I LUV YOU SLADE BANKS OF THE OHIO OLIVIA NEWTON-JOHN MORE THAN A FEELING BOSTON FEELING ALRIGHT JOE COCKER GOOD FEELIN MAX MERRITT PEACEFUL EASY FEELING EAGLES HELLO ITS ME TODD RUNDGREN EBONY EYES BOB WELCH STAR SONG MARTY RHONE EGO (IS NOT A DIRTY WORD) SKYHOOKS ON THE COVER OF THE ROLLING STONE DR HOOK I HEAR YOU KNOCKING DAVE EDMUNDS EVERLASTING LOVE ANDY GIBB LET'S PRETEND RASPBERRIES WHO'LL STOP THE RAIN CREEDENCE CLEARWATER REVIVAL BICYCLE RACE QUEEN YOU TOOK THE WORDS RIGHT OUT OF MY MOUTH (HOT SU MEAT LOAF CAPTAIN ZERO MIXTURES SWEET -

Sizzling 70'S! 14-15 November 2020 Military Madness

SIZZLING 70’S! 14-15 NOVEMBER 2020 MILITARY MADNESS GRAHAM NASH NOWHERE MAN SHERBET LISTEN TO THE MUSIC DOOBIE BROTHERS AMERIKAN MUSIC ALISON DURBIN I HATE THE MUSIC JOHN PAUL YOUNG EVERY TIME I THINK OF YOU THE BABYS THINK ABOUT TOMORROW TODAY MASTER'S APPRENTICES DRAGGIN' THE LINE TOMMY JAMES ROCKET MAN ELTON JOHN LOOK AFTER YOURSELF STARS RICH GIRL HALL & OATES BREAKING UP IS HARD TO DO PARTRIDGE FAMILY YOU ANGEL YOU MANFRED MANN'S EARTH BAND UNCLE ALBERT/ADMIRAL HALSEY PAUL McCARTNEY DECEMBER 1963 (OH WHAT A NIGHT) FOUR SEASONS LOVE ON THE RADIO SKYHOOKS YOU AND ME ALICE COOPER ORCHESTRA LADIES ROSS RYAN LYIN' EYES THE EAGLES FLY ROBIN, FLY SILVER CONVENTION GO YOUR OWN WAY FLEETWOOD MAC 39 QUEEN WHO'LL STOP THE RAIN CREEDENCE CLEARWATER REVIVAL GYPSY QUEEN COUNTRY RADIO HEART OF GLASS BLONDIE TIN MAN AMERICA JAM UP JELLY TIGHT TOMMY ROE HELP IS ON ITS WAY LITTLE RIVER BAND DARKTOWN STRUTTERS BALL TED MULRY GANG LAST TRAIN TO LONDON ELECTRIC LIGHT ORCHESTRA HOOKED ON A FEELING BLUE SWEDE EVERY NIGHT PHOEBE SNOW HERE WE GO JOHN PAUL YOUNG LAY DOWN SALLY ERIC CLAPTON KONKEROO DRAGON SHILO NEIL DIAMOND LAST TIME I SAW HIM DIANA ROSS LOVE HER MADLY THE DOORS JAMIE COME HOME JAMIE DUNN THE BITCH IS BACK ELTON JOHN THE BOYS ARE BACK IN TOWN THIN LIZZY WELCOME BACK JOHN SEBASTIAN BACK AGAIN STARS YOU'RE THE ONE THAT I WANT OLIVIA NEWTON-JOHN/JOHN TRAVOLTA AIN'T GONNA BUMP NO MORE (WITH NO BIG FAT WOMAN) JOE TEX NO MORE MR NICE GUY ALICE COOPER I CAN SEE CLEARLY NOW JOHNNY NASH RIKKI, DON'T LOOSE THAT NUMBER STEELY DAN STAND BY ME JOHN LENNON -

Australian and New Zealand Karaoke Song Book

Australian & NZ Karaoke Songs by Artist Karaoke Shack Song Books Title DiscID Title DiscID 1927 Allison Durbin If I Could CKA16-06 Don't Come Any Closer TKC14-03 If I Could TKCK16-02 I Have Loved Me A Man NZ02-02 ABBA I Have Loved Me A Man TKC02-02 Waterloo DU02-16 I Have Loved Me A Man TKC07-11 AC-DC Put Your Hand In The Hand CKA32-11 For Those About To Rock TKCK24-01 Put Your Hand In The Hand TKCK32-11 For Those About To Rock We Salute You CKA24-14 Amiel It's A Long Way To The Top MRA002-14 Another Stupid Love Song CKA22-02 Long Way To The Top CKA04-01 Another Stupid Love Song TKC22-15 Long Way To The Top TKCK04-08 Another Stupid Love Song TKCK22-15 Thunderstruck CKA18-18 Anastacia Thunderstruck TKCK18-01 I'm Outta Love CKA13-04 TNT CKA21-03 I'm Outta Love TKCK13-01 TNT TKCK21-01 One Day In Your Life MRA005-15 Whole Lotta Rosie CKA25-10 Androids, The Whole Lotta Rosie TKCK25-01 Do It With Madonna CKA20-12 You Shook Me All Night Long CKA01-11 Do It With Madonna TKCK20-02 You Shook Me All Night Long DU01-15 Angels, The You Shook Me All Night Long TKCK01-10 Am I Ever Gonna See Your Face Again CKA01-03 Adam Brand Am I Ever Gonna See Your Face Again TKCK01-08 Dirt Track Cowboy CKA28-17 Dogs Are Talking CKA30-17 Dirt Track Cowboy TKCK28-01 Dogs Are Talking TKCK30-01 Get Loud CKA29-17 No Secrets CKA33-02 Get Loud TKCK29-01 Take A Long Line CKA05-01 Good Friends CKA28-09 Take A Long Line TKCK05-02 Good Friends TKCK28-02 Angus & Julia Stone Grandpa's Piano CKA19-14 Big Jet Plane CKA33-05 Grandpa's Piano TKCK19-07 Anika Moa Last Man Standing CKA14-13 -

Low Frequency Noise Emission Dynamics of Reactor Fuel Plates Noise from Licensed Premises Road Traffic Noise in Denmark

Low frequency noise emission Dynamics of reactor fuel plates Noise from licensed premises Road traffic noise in Denmark Australian Acoustical Society Vol. 39 No. 1 April 2011 EDITORIAL COMMITTEE: Nicole Kessissoglou , Marion Vol 39 No. 1 April 2011 Burgess, Tracy Gowen BUSINESS MANAGER: Leigh Wallbank PAPERS Acoustics Australia A simple outdoor criterion for assessment of low frequency noise emission General Business Norm Broner. Page 7 (subscriptions, extra copies, back issues, advertising, etc.) Relationship between natural frequencies and pull out force for plates Mrs Leigh Wallbank with two clamped edges P O Box 70 Mauro Caresta and David Wassink . Page 15 OYSTER BAY NSW 2225 Tel (02) 9528 4362 Fax (02) 9589 0547 TECHNICAL NOTES [email protected] Assessing noise from licensed premises - Are we on the same page? Acoustics Australia All Editorial Matters Glenn Wheatley . Page 19 (articles, reports, news, book reviews, new products, etc) Noise abatement measures in Denmark The Editor, Acoustics Australia c/o Nicole Kessissoglou Gilles Pigasse and Hans Bendtsen . Page 21 School of Mechanical and Manufacturing Engineering University of New South Wales Sydney 2052 Australia News. 27 61-2-93854166 (tel) Prizes & Awards . 27 61-2-96631222 (fax) [email protected] Meeting Reports . 28 www.acoustics.asn.au Standards Australia . 28 Australian Acoustical Society FASTS . 28 Enquiries see page 38 Future Conferences & Workshops . 29 Acoustics Australia is published by the New Products . 29 Australian Acoustical Society (A.B.N. 28 000 712 658) Scanning International News . 29 ISSN 0814-6039 Diary . 30 Responsibility for the contents of Sustaining Members. 32 articles and advertisements rests upon the contributors and not the Australian Advertiser Index . -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Karaoke Collection Title Title Title +44 18 Visions 3 Dog Night When Your Heart Stops Beating Victim 1 1 Block Radius 1910 Fruitgum Co An Old Fashioned Love Song You Got Me Simon Says Black & White 1 Fine Day 1927 Celebrate For The 1st Time Compulsory Hero Easy To Be Hard 1 Flew South If I Could Elis Comin My Kind Of Beautiful Thats When I Think Of You Joy To The World 1 Night Only 1st Class Liar Just For Tonight Beach Baby Mama Told Me Not To Come 1 Republic 2 Evisa Never Been To Spain Mercy Oh La La La Old Fashioned Love Song Say (All I Need) 2 Live Crew Out In The Country Stop & Stare Do Wah Diddy Diddy Pieces Of April 1 True Voice 2 Pac Shambala After Your Gone California Love Sure As Im Sitting Here Sacred Trust Changes The Family Of Man 1 Way Dear Mama The Show Must Go On Cutie Pie How Do You Want It 3 Doors Down 1 Way Ride So Many Tears Away From The Sun Painted Perfect Thugz Mansion Be Like That 10 000 Maniacs Until The End Of Time Behind Those Eyes Because The Night 2 Pac Ft Eminem Citizen Soldier Candy Everybody Wants 1 Day At A Time Duck & Run Like The Weather 2 Pac Ft Eric Will Here By Me More Than This Do For Love Here Without You These Are Days 2 Pac Ft Notorious Big Its Not My Time Trouble Me Runnin Kryptonite 10 Cc 2 Pistols Ft Ray J Let Me Be Myself Donna You Know Me Let Me Go Dreadlock Holiday 2 Pistols Ft T Pain & Tay Dizm Live For Today Good Morning Judge She Got It Loser Im Mandy 2 Play Ft Thomes Jules & Jucxi So I Need You Im Not In Love Careless Whisper The Better Life Rubber Bullets 2 Tons O Fun