Cross Examination and How Psychological Evidence Can Assist Judicial Decision Making

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Bar Association Act, 5721-1961 Full Updated Version

The Bar Association Act, 5721-1961 Full updated version The Bar Association Act, 5721-1961 Private Law & Economics – Regulation of Occupation – Lawyers Authorities & Administrative Law – Regulation of Occupation – Lawyers Table of Contents Clause 1 Establishing the Bar Clause 2 Functions of the Bar Clause 3 Activities of the Bar Clause 4 The Bar – a corporation Clause 4a Place of domicile of the Bar Clause 5 The Bar – an audited entity First Chapter: The Bar's Institutions Clause 6 The Bar's Institutions Clause 6a Restriction on term Clause 8 Head of the Bar Clause 8a Deputy Head of the Bar Clause 8b Election of Head of the Bar by the Council Clause 8c Removing the Head of the Bar from office Clause 9 The National Council Clause 9a Filling a vacant place on the National Council Clause 9b Ending of term of office due to absence from Council meetings Clause 10 Term of office Clause 11 The central committee Clause 11a A Central Committee member whose place becomes vacant Clause 11b Managing Central Committee meetings and determining the agenda Clause 12 Districts of the Bar Association Second Chapter: The Bar Institutions Clause 12a Registration of Bar members in the Districts Clause 13 Composition of the District Committee Clause 14 National Disciplinary Court Clause 15 District disciplinary courts Clause 16 Fitness to serve as a member of a disciplinary court Clause 17 Termination of office of members of disciplinary courts Clause 17a Expiry of Disciplinary Court member's term Clause 17a1 Suspension of member of a disciplinary court Clause -

Supreme Judicial Court Rule 3:12: Code of Professional Responsibility for Clerks of the Courts CANON 1

Supreme Judicial Court Rule 3:12: Code of Professional Responsibility for Clerks of the Courts CANON 1. Purpose and Applicability. This Code shall be known as the "Code of Professional Responsibility for Clerks of the Courts of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts." Its purpose is to define norms of conduct and practice appropriate to persons serving in the positions covered by the Code and thereby to contribute to the preservation of public confidence in the integrity, impartiality, and independence of the courts. The word "Clerk Magistrate" in this Code, unless otherwise expressly provided, shall mean anyone serving in the position of Clerk Magistrate, Clerk, Register, Recorder, Assistant Clerk Magistrate, Assistant Clerk, Assistant Register, or Deputy Recorder, Judicial Case Manager or Assistant Judicial Case Manager, in the Supreme Judicial Court, the Appeals Court, or a Department of the Trial Court of the Commonwealth, whether elected or appointed, and whether serving in a permanent or temporary capacity. The words "elected Clerk Magistrate" shall also include a person who is appointed to complete the term of an elected Clerk Magistrate. The word "court" in this Code shall mean the Supreme Judicial Court, the Appeals Court, a particular division of a Department of the Trial Court, or a particular Department of the Trial Court if the Department does not have divisions. CANON 2. Compliance with Statutes and Rules of Court. A Clerk Magistrate shall comply with the laws of the Commonwealth, rules of court, and lawful directives of the several judicial authorities of the Commonwealth. The words "judicial authorities" in this Code, unless otherwise expressly provided, shall mean the Justices of the Supreme Judicial Court and Appeals Court, the Chief Administrative Justice of the Trial Court, the Administrative Justices of the several Departments of the Trial Court, or Associate Justices of the Trial Court, as is appropriate under the circumstances. -

Bar Council News Update ‒ Monday 23 October 2017

BAR COUNCIL NEWS UPDATE – MONDAY 23 OCTOBER 2017 Online justice Buzzfeed – Emily Dugan writes on Transform Justice’s report on the use of virtual technology in court, published today: [R]esearch by the charity Transform Justice, based on interviews and a survey of people across the legal world, has suggested the use of video seriously impacts on the chance of a fair hearing. The situation is particularly difficult for the rising number of defendants who cannot afford a lawyer to be in the courtroom for them. Chair of the Bar, Andrew Langdon QC, said: “Government plans to invest in virtual technology for court hearings hold the promise of savings and greater efficiency but we must recognise that they also pose a real threat to the quality of justice. “Barristers who appear regularly in courts or tribunals will tell you that many strictly procedural hearings could take place via conference calls or video link without any detriment to the quality of justice. But they will also tell you that the quality of justice can suffer and that outcomes can be different when we lose face-to-face contact between judges, witnesses, victims, clients and their lawyers. This is especially so when dealing with people who have mental health problems, intellectual disabilities or who are otherwise vulnerable.” Legal Aid New Law Journal – Sir Geoffrey Bindman QC writes on the Bach Commission report, ‘The Right to Justice’. He writes: The final report of the Bach Commission is an admirable blueprint for the restoration of our justice system. Lord Bach has stressed that the commission was made up of people selected for their expertise rather than any affiliation with the Labour Party . -

Municipal Court Recorder July 2003 from the GENERAL COUNSEL W

Volume 12 JULY 2003 No. 5 ©2003 Texas Municipal Courts Education Center, Austin. Funded by a grant from the Court of Criminal Appeals. Magistrate’s Order After the MOEP: What for Emergency Happens Next? Protection By Robert J. Gradel, Municipal Judge, Lampasas By Kimberly A.F. Piechowiak, Assistant City Attorney II You head down to the jail on Sunday morning about 8:00 Family Violence Prosecutor, San Antonio a.m. Eleven people have been arrested overnight, and your Sunday School class begins at 9:00 a.m., so you have no In cases of domestic violence, victim safety should be a time to waste. Waiting for you is a woman (and her primary concern. State law has been crafted to emphasize mother) who wants an emergency protective order. She this priority, not only for law enforcement personnel and tells you that her husband has an alcohol abuse problem. prosecutors, but also for judicial officers. Article 5.01(b) of Last night, he clenched his fists like he was going to hit her, the Texas Code of Criminal Procedure states: called her bad names, threatened her, pushed her, and In any law enforcement, prosecutorial, or judicial threw the remote at her, all in front of the children. She response to allegations of family violence, the has no visible red marks, bruises, or abrasions. He has responding law enforcement or judicial officers shall done this before, but she never called the police. They have protect the victim, without regard to the relationship been married 10 years and have three children. The police between the alleged offender and victim. -

Forms of Dress and Address in the Higher Courts and Some Practical Tips

Forms of dress and address in the Higher Courts and some practical tips Court dress Court dress in the criminal courts is easily identifiable as there is specific guidance from the Lord Chief Justice in the form of the Criminal Procedure Directions General Application A: COURT DRESS. However that guidance is limited, to appearing without robes or wigs in the magistrates, and in the crown court wearing gowns and wigs. Wigs are wigs, and for junior advocates only come in one type, no matter which side of the advocate divide you fall on. The gown is always a Solicitors' gown. These basics should also be accompanied by a collar and bands (or collarette for female advocates) which are the same for both sexes and both professions. In the civil courts, there is even less guidance, the last formal guidance having been withdrawn. Discussions abound and as always guidance is said to be due to be released shortly. What dress is expected often varies dependent upon the judge, and you will learn from experience and advice from court clerks. In the Senior Courts (Higher Courts), the dress for civil cases is normally robed, however, there are many variations to this. For instance, urgent Queen's Bench Division (QBD) cases are normally argued un-robed, unless they are committal cases in which instance they are often robed. Many of the specialist courts also see advocates normally appearing unrobed. Unisex dress advice Suits must be black, navy blue or dark charcoal grey and same for shoes. Bands and collarettes should be starched. Hair should not poke out below the sides of your wig. -

Recorder Competition – 2015 Selection Exercise

RECORDER COMPETITION – 2015 SELECTION EXERCISE THE OUTCOME: THE PROFESSIONAL BACKGROUND OF THOSE WHO WERE APPOINTED ______________________ This information supplements the information already provided to the Judicial Appointments Commission in the ChBA’s “Feedback Report” dated 25 September 2015 in relation to the qualifying test which took place on 7 May 2015 and the ChBA’s “Supplementary Feedback Report” dated 25 November 2015 in relation to the second stage of shortlisting. The outcome of the 2015 Recorder selection exercise was that: 1. Only 11 (17%) of the 64 recorders appointed to sit in crime have non-criminal practices, whereas 53 (83%) have criminal practices. However, of those 11 who now have non-criminal practices, 3 have had significant criminal practices in the past, and a further three have had some experience of criminal practice. It appears that only 5 (8%) of the 64 recorders appointed to sit in crime do not have any experience of criminal practice. 2. Only 2 (5%) of the 35 recorders appointed to sit in family have non-family practices, whereas 33 have practices in family law. This information is derived from the published list of recorders at https://www.judiciary.gov.uk/announcements/recorder-appointments/. The analysis, which is appendixed hereto, was carried out by one of the officers of the ChBA by reference to individual profiles available on a chambers or firm website and the Bar Directory (2015). The outcome of the 2015 Recorder Competition for civil practitioners wishing to sit in crime or family is therefore broadly similar to the 2011 Recorder Competition (when the qualifying test was based on the actual jurisdiction of criminal or family law). -

Recorder Vol. 20 No. 5.Indd

Volume 20 August 2011 No. 5 © 2011 Texas Municipal Courts Education Center. Funded by a grant from the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals. INSIDE THIS ISSUE LLegislativeegislative Features Court Costs and Administrative UUpdatepdate Issues ................................................ 19 Juvenile Justice and Issues Relating to Children ....................................... 45 Magistrates Issues and Domestic Violence ........................................... 13 Ordinance and Local Government Issues ................................................ 42 Procedural Law ................................ 1 Substantive Criminal Law ................ 28 Traffi c Safety and Transportation Code Amendments ........................... 64 PROCEDURAL LAW Charts The Big Three................................... 81 Registration-Inspection-Financial — High Priority — Responsibility Requirements H.B. 27 will increase the likelihood Comparisons of Deferred Options ... 11 Subject: Compulsory Installment of defendants paying off the full Court Costs ...................................... 26 Payments of Fines and Costs by amount of the fi ne in a more effi cient Defenses to Prosecution ................... 80 Defendants Who Are Unable to Pay and timely manner. the Fines and Costs Municipal Juvenile/Minor ................ 55 New Class A and B Misdemeanors .. 41 H.B. 27 Commentary: Without the aid Effective: September 1, 2011 of the Code Construction Act New Class C/Fine-Only Offenses .... 40 (particularly, Section 311.023 of the New Punishments for Old Crimes .. -

David Bedingfield Alum Profile: Mark D. Hobson

January 17, 2020 From the Dean Participants in SBA's 2019 Law Classic golf tournament On behalf of our award-winning Student Bar Association (SBA), we would like to invite alumni and students to SBA’s upcoming Journey to Justice 5K and Fourth Annual FSU Law Classic golf tournament. The 5K is scheduled for Saturday, February 8, at Langford Green by FSU’s Doak Campbell Stadium. Through the event, which will benefit the Legal Aid Foundation of Tallahassee, SBA students hope to bring together the FSU Law community to promote physical and mental health, and expand the ways in which SBA provides activities for students to release tension. Visit SBA’s website for more information and to register. SBA’s Fourth Annual Law Classic is scheduled for Saturday, March 7, at the Killearn Country Club in Tallahassee. The golf tournament has been very successful in bringing together students and alumni in previous years and you can register online now for this year’s event, which will feature a shotgun-style start and will include lunch. Anyone interested in more information about participating in the tournament or sponsorship opportunities can email SBA Vice President Kaitlyn Kelley or SBA President Breanna Raspopovich. Congratulations to our SBA students on organizing these ambitious events! - Dean Erin O'Connor Faculty Profile: David Bedingfield David Bedingfield, a barrister in London, is a visiting professor at the FSU College of Law for the spring 2020 semester. He is teaching Immigration Law and Comparative Family Law. Bedingfield has developed courses in advocacy techniques, and has lectured extensively regarding international movement of children, the adoption and placement of abused children, and human rights in the family law context. -

The Fair Defense Act and the Role of the Magistrate

Volume 24 February 2015 No. 2 © 2015 Texas Municipal Courts Education Center. Funded by a grant from the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals. The Fair Defense Act and the Role of the Magistrate By Jim Bethke, Executive Director, Texas Indigent Defense Texas Code of Criminal Procedure, Article 1.051(c), Commission and Dottie Carmichael, Ph.D., Research provides that “an indigent defendant is entitled to have Scientist, Public Policy Research Institute (PPRI), Institute an attorney appointed to represent him in any adversary at Texas A&M University. A special thank you is owed judicial proceeding that may result in punishment by Brittany Long, 3L, University of Texas School of Law for confinement and in any other criminal proceeding if her editorial assistance. the court concludes that the interests of justice require representation.”1 In 2001, the 77th Texas Legislature Introduction modified the State’s statutes and codes to reform indigent defense practices through a group of amendments In 2005, there were a series of articles published in The collectively known as “The Fair Defense Act.” Prior to Recorder describing magistrates’ responsibilities under the Fair Defense Act, an absence of uniform standards the Fair Defense Act passed in 2001. Since then, the Texas and procedures combined with a lack of State oversight Legislature has met four times and convened once again on allowed indigent defense rules and the quality of January 13. Additionally, the U.S. Supreme Court issued representation to vary widely from county to county and an opinion directly impacting Article 15.17 hearings, as even from courtroom to courtroom.2 The accused in Texas has the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals. -

The Electronic Lawyer, 58 Depaul L

University of California, Hastings College of the Law UC Hastings Scholarship Repository Faculty Scholarship 2009 The lecE tronic Lawyer Richard L. Marcus UC Hastings College of the Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.uchastings.edu/faculty_scholarship Part of the Civil Procedure Commons Recommended Citation Richard L. Marcus, The Electronic Lawyer, 58 DePaul L. Rev. 263 (2009). Available at: http://repository.uchastings.edu/faculty_scholarship/451 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Faculty Publications UC Hastings College of the Law Library Marcus Richard Author: Richard L. Marcus Source: DePaul Law Review Citation: 58 DePaul L. Rev. 263 (2009). Title: The Electronic Lawyer Originally published in DEPAUL LAW REVIEW. This article is reprinted with permission from DEPAUL LAW REVIEW and Depaul University College of Law. THE ELECTRONIC LAWYER Richard L. Marcus* I. INTRODUCTION The organizers of this conference have asked us to reflect on future challenges for the legal profession.1 I begin with an image from popu- lar culture. Anyone who has seen the movie Michael Clayton has seen 2 one vision of the future (or possibly contemporary) American lawyer. In the movie, George Clooney plays the title role as a lawyer who works for a 600-lawyer New York law firm that is acting as the "fixer" for a large agricultural products company sued for allegedly causing the deaths of small farmers in the Midwest. -

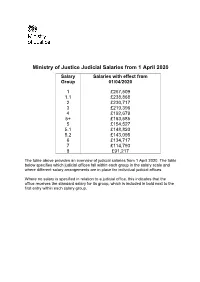

Ministry of Justice Judicial Salaries from 1 April 2020 Salary Salaries with Effect from Group 01/04/2020

Ministry of Justice Judicial Salaries from 1 April 2020 Salary Salaries with effect from Group 01/04/2020 1 £267,509 1.1 £238,868 2 £230,717 3 £219,396 4 £192,679 5+ £163,585 5 £154,527 5.1 £148,820 5.2 £143,095 6 £134,717 7 £114,793 8 £91,217 The table above provides an overview of judicial salaries from 1 April 2020. The table below specifies which judicial offices fall within each group in the salary scale and where different salary arrangements are in place for individual judicial offices. Where no salary is specified in relation to a judicial office, this indicates that the office receives the standard salary for its group, which is included in bold next to the first entry within each salary group. Judge Title and Salary Group Includes Salaries Salaries Salaries w.e.f. w.e.f w.e.f 01/04/19 01/10/19 01/04/20 Salary Group 1 262,264 262,264 267,509 Lord Chief Justice Salary Group 1.1 234,184 234,184 238,868 Lord Chief Justice of Northern Ireland Lord President of the Court of Session (Scotland) Master of the Rolls President of the Supreme Court Salary Group 2 226,193 226,193 230,717 Chancellor of the High Court Deputy President of the Supreme Court Justices of the Supreme Court Lord Justice Clerk (Scotland) President of the Family Division President of the Queen’s Bench Division Senior President of Tribunals Salary Group 3 215,094 215,094 219,396 Inner House Judges of the Court • President of Scottish of Session (Scotland) Tribunals Lords/Lady Justices of Appeal • Senior Presiding Judge • Deputy Senior Presiding Judge • Deputy Head -

A PRIVILEGE to BE RECORDER It Is Nearly the End of My Must Endure in Order to Respond to However That May Be

News from the South Eastern Circuit THE CIRCUITEER INSIDE THIS ISSUE 06 12 16 22 23 Keble Advanced Some British The Anglo-Israel Importation of Military Advocacy Course lawyers abroad… Scholarship Child Sex Dolls – a justice – an need for guidance unfair system? A PRIVILEGE TO Youth BE RECORDER Justice by Valerie Charbit Legal It is nearly the end of my term as Recorder of the Centre South Eastern Circuit by Kate Aubrey-Johnson and I have enjoyed the privilege of assisting two inspirational leaders, each ARE YOU A YOUTH so supportive of the bar and the profession. JUSTICE SPECIALIST? See page 10 See page 18 When my friends and family ARE YOU asked me to ACROSS describe what EATING my experience at the Keble College THE POND course was like, SAFELY? lawyer boot camp was a phrase TO KEBLE by Richard Heller that came to mind. Sentencing corporates by Cameron Carstens and individuals for food safety breaches See page 14 See page 8 THE CIRCUITEER Issue 44 / December 2017 1 News from the South Eastern Circuit EDITOR’S COLUMN Looking out over the sun- Our charismatic Recorder, litigation involving vulnerable drenched Algarve coast makes Valerie Charbit, says her witnesses become known. I one wonder, just a little, why goodbyes and leaves a fantastic have no doubt that successive we are so wedded to the world legacy: the importance of governments will see this as of work. The answer, of course, considering Wellness at the a soft target for law-making is that it makes the refreshing Bar has now become widely to sate their desire to appear ‘long weekend’ achievable.