Geriatric Psychiatry Study Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Neuropsychiatric Symptoms in the Prodromal Stages of Dementia

1 Neuropsychiatric Symptoms in the Prodromal Stages of Dementia Florindo Stella, Márcia Radanovic, Márcio L.F. Balthazar, Paulo R. Canineu, Leonardo C. de Souza, Orestes V. Forlenza Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2014;27(3):230-235. Abstract and Introduction Abstract Purpose of Review. To critically discuss the neuropsychiatric symptoms in the prodromal stages of dementia in order to improve the early clinical diagnosis of cognitive and functional deterioration. Recent Findings. Current criteria for cognitive syndrome, including Alzheimer's disease, comprise the neuropsychiatric symptoms in addition to cognitive and functional decline. Although there is growing evidence that neuropsychiatric symptoms may precede the prodromal stages of dementia, these manifestations have received less attention than traditional clinical hallmarks such as cognitive and functional deterioration. Depression, anxiety, apathy, irritability, agitation, sleep disorders, among other symptoms, have been hypothesized to represent a prodromal stage of dementia or, at least, they increase the risk for conversion from minor neurocognitive disorder to major neurocognitive disorder. Longitudinal investigations have provided increased evidence of progression to dementia in individuals with minor neurocognitive disorder when neuropsychiatric symptoms also were present. Summary. Although neuropsychiatric symptoms are strongly associated with a higher risk of cognitive and functional deterioration, frequently the clinician does not acknowledge these conditions as increasing the -

Geriatric Medicine and Why We Need Geriatricians! by Juergen H

Geriatric Medicine and why we need Geriatricians! by Juergen H. A. Bludau, MD hat is geriatric medicine? Why is there a need for 1. Heterogeneity: As people age, they become more Wthis specialty? How does it differ from general heterogeneous, meaning that they become more and more internal medicine? What do geriatricians do differently when different, sometimes strikingly so, with respect to their they evaluate and treat an older adult? These are common health and medical needs. Imagine for a moment a group questions among patients and physicians alike. Many of 10 men and women, all 40 years old. It is probably safe internists and family practitioners argue, not unjustifiably, to say that most, if not all, have no chronic diseases, do not that they have experience in treating and caring for older see their physicians on a regular basis, and take no long- patients, especially since older adults make up almost half of term prescription medications. From a medical point of all doctors visits. So do we really need another type of view, this means that they are all very similar. Compare this physician to care for older adults? It is true that geriatricians to a group of 10 patients who are 80 years old. Most likely, may not necessarily treat older patients differently per se. But you will find an amazingly fit and active gentleman who there is a very large and important difference in that the focus may not be taking any prescription medications. On the of the treatment is different. In order to appreciate how other end of the spectrum, you may find a frail, memory- significant this is, we need to look at what makes an older impaired, and wheelchair-bound woman who lives in a adult different from a younger patient. -

2019, Rev. 1 BH:Adult and Geriatric Psychiatry Adult and Geriatric Psychiatry

InterQual® 2019, Rev. 1 BH:Adult and Geriatric Psychiatry Adult and Geriatric Psychiatry Overview Select Level of Care Intensive Outpatient Program (1, 2) Notes InterQual® criteria (IQ) is confidential and proprietary information and is being provided to you solely as it pertains to the information requested. IQ may contain advanced clinical knowledge which we recommend you discuss with your physician upon disclosure to you. Use permitted by and subject to license with Change Healthcare LLC and/or one of its subsidiaries. IQ reflects clinical interpretations and analyses and cannot alone either (a) resolve medical ambiguities of particular situations; or (b) provide the sole basis for definitive decisions. IQ is intended solely for use as screening guidelines with respect to medical appropriateness of healthcare services. All ultimate care decisions are strictly and solely the obligation and responsibility of your health care provider. © 2019 Change Healthcare LLC and/or one of its subsidiaries. All Rights Reserved. Overview Informational Notes The Adult and Geriatric Psychiatry Criteria are for the review of patients who are ages 18 and older. InterQual® content contains numerous references to gender. Depending on the context, these references may refer to either genotypic or phenotypic gender. At the individual patient level, a variety of factors, including, but not limited to, gender identity and gender reassignment via surgery or hormonal manipulation, may affect the applicability of some InterQual criteria. This is most often the case with genetic testing and procedures that assume the presence of gender−specific anatomy. With these considerations in mind, all references to gender in InterQual have been reviewed and modified when appropriate. -

Fundamentals of Geriatric Pharmacotherapy, 2Nd Edition

PART 1 Social, Ethical, and Economic Issues of Aging 1 Challenges in Geriatric Care REBECCA B. SLEEPER Learning Objectives 1. Evaluate the applicability of clinical literature to the elderly patient using an approach that is tailored to specific subgroups of the geriatric population. 2. Differentiate the roles of healthcare professionals and the various services and venues available in the care of geriatric patients. 3. Infer scenarios in which geriatric patients are at risk for suboptimal care and intervene when breakdowns in the continuum of care are identified. 4. Recognize the impact of caregiver burden on patient outcomes. Key Terms and Definitions ASSISTED LIVING FACILITY: Living environment that provides added services to the individual who is safe to live in the community environment but requires some assistance with various daily activities. CAREGIVER BURDEN: Psychosocial and physical stress experienced by an individual who provides care to another person. CERTIFIED GERIATRIC PHARMACIST: Pharmacist who has achieved certification from the Commission for Certification in Geriatric Pharmacy. CERTIFIED NURSE’S ASSISTANT: Individual who has earned a certificate to practice as a nurse’s assistant and who may work in a wide variety of healthcare settings ranging from long-term care facilities to private homes. GERIATRIC: Adjective generally used to refer to an older individual. GERIATRICIAN: Physician with expertise, as demonstrated by fellowship or other added qualifications, in the care of older persons. GERONTOLOGICAL NURSE: Nurse with expertise, as demonstrated by exam or other added qualifications, in the care of older persons. 4 | Fundamentals of Geriatric Pharmacotherapy INFORMAL CAREGIVER: An individual who does not have formal training as a healthcare professional but who provides daily care to another individual; usually unpaid. -

Geriatric Psychopharmacology: Anti-Depressants Amber Mackey, D.O

Geriatric Psychopharmacology: Anti-depressants Amber Mackey, D.O. University of Reno School of Medicine Department of Psychiatry Chief Resident, PGY-4 Pharmacologic issues in the elderly More likely to experience drug induced adverse events Cardiac effects: Prolonged QTc, arrhythmias, sudden death Peripheral/central anticholinergic effects: constipation, delirium, urinary retention, delirium, and cognitive dysfunction Antihistaminergic effects: sedation Antiadrenergic effects: postural hypotension Other effects: Hyponatremia, bleeding, altered bone metabolism Pharmacokinetic Organ system Change consequence Circulatory system Decreased concentration Increased or decreased of plasma albumin and free concentration of drugs increased α1-acid in plasma glycoprotein Gastrointestinal Table tract 20-1 Decreased intestinal and Decreased rate of drug splanchnic blood flow absorption Kidney Decreased glomerular Decreased renal filtration rate clearance of active metabolites Liver Decreased liver size; Decreased hepatic decreased hepatic blood clearance flow; variable effects on cytochrome P450 isozyme activity Muscle Decreased lean body mass Altered volume of and increased adipose distribution of lipid-soluble tissue drugs, leading to increased elimination half-life Table 20-1, Physiological changes in elderly persons associated with altered pharmacokinetics, American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Geriatric Psychiatry, Fifth Edition, Chapter 20: Psychopharmacology. Other issues Illnesses that effect the elderly also play a role in diminishing -

Revealing a Blind Spot on the Global Mental Health Map: Scoping Review

Revealing a blind spot on the global mental health map: scoping review of 25 years development of mental health care for people with severe mental illnesses in Central and Eastern Europe Authors PhDr. Petr Winkler* 1,3; Dzmitry Krupchanka* 1,3,4 PhD; Tessa Roberts2 MSc; Lucie Kondratova1 MSc; Vendula Machů1; Prof Cyril Höschl1 DrSc; Prof Norman Sartorius5 PhD; Prof Robert Van Voren6,7, 29, PhD; Oleg Aizberg8 PhD; Prof Istvan Bitter9 PhD; Arlinda Cerga-Pashoja2 PhD; Azra Deljkovic10 MD; Naim Fanaj11 PhD, ; Arunas Germanavicius12 PhD; Hristo Hinkov13 PhD; Aram Hovsepyan14 MD; Fuad N. Ismayilov1515, 30 DrSc; Prof Sladana Strkalj Ivezic1616,1717 DrSc; Marek Jarema1818 PhD; Vesna Jordanova1919 MD; Selma Kukić20; Nino Makhashvili2121 PhD; Brigita Novak Šarotar2222,2323 PhD; Oksana Plevachuk2424 PhD; Daria Smirnova2525 PhD; Bogdan Ioan Voinescu2626,2727 PhD; Jelena Vrublevska2828 MD; and Prof Graham Thornicroft PhD3 *Both authors contributed equally Institutions 1. Department of Social Psychiatry, National Institute of Mental Health, Prague, Czech Republic 2. Department of Population Health, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, London, UK 3. Health Service and Population Research Department, Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience, King’s College London, London, UK 4. Institute of Global Health, University of Geneva, Geneva, Switzerland 5. Association for the Improvement of Mental Health Programmes, Geneva, Switzerland 6. Ilia State University, Tbilisi, Georgia 7. Vytautas Magnus University, Kaunas, Lithuania 8. Department of Psychiatry and Narcology, Belarusian Medical Academy of Postgraduate Education, Minsk, Belarus 9. Department of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, Semmelweis University, Budapest, Hungary 10. Mental Health Center, Health Care Center Pljevlja, Plevlja, Montenegro 11. Mental Health Center, Prizren, Kosovo 12. -

Partnership for Health in Aging

Partnership FOR HealthiN Aging Multidisciplinary Competencies in the Care of Older Adults at the Completion of the Entry-level Health Professional Degree Preface In June 2008, the American Geriatrics Society convened a A workgroup of healthcare professionals with experience meeting of 21 organizations representing healthcare pro- in competency development, certification, and accredita- fessionals who care for older adults to discuss how these tion was convened in February 2009. Workgroup mem- organizations could work together to: bers represent ten healthcare disciplines: • advance recommendations from the 2008 Institute • Dentistry of Medicine Report, Retooling for an Aging America: • Medicine Building the Health Care Workforce, and • Nursing • advocate for ways to meet the healthcare needs of the • Nutrition nation’s rapidly growing older population. • Occupational Therapy This meeting led to the development of a loose coalition – • Pharmacy the Partnership for Health in Aging (PHA) – that identi- • Physical Therapy fied as its first step the development of a set of core com- • Physician Assistants petencies in the care of older adults that are relevant to and • Psychology can be endorsed by all health professional disciplines. • Social Work The workgroup began with a comprehensive matrix of The workgroup reviewed all comments received, and competencies across these ten disciplines. (Note: These developed the final set of competencies on the following disciplines are currently at different stages in developing page. The set describes essential skills that healthcare discipline-specific geriatrics competencies). Through an professionals in the above ten disciplines should have, iterative process, the workgroup drafted a set of baseline and necessary approaches they should master, by the time competencies that were circulated among more than they complete their entry-level degree, in order to provide 25 professional organizations for review and comment. -

GERIATRIC MEDICINE What Is Geriatric Medicine?

GERIATRIC MEDICINE What is Geriatric Medicine? Geriatrics is the branch of medicine that focuses on health promotion, prevention, and diagnosis and treatment of disease and disability in older adults. In recent surveys, geriatricians are among the most satisfied physicians in terms of their choice of specialty. Geriatrics offers a wide diversity of career options and is a clinically and intellectually rewarding discipline given the medical complexity of older adults. Geriatricians reap the rewards of making a difference in a patient’s level of independence, well- being and quality of life. With the rapid growth of the older population in the United States, there is a pressing demand for physicians with specialized training in geriatrics. ama-assn.org/specialty/geriatric-medicine The Birth of “Geriatric” Medicine • In 1909, Austrian born physician, Ignatz Leo Nascher coined the term “geriatrics” for care of the elderly, explaining, “Geriatrics, from geras, old age, and iatrikos, relating to the physician, is a term I would suggest as an addition to our vocabulary, to cover the same field in old age that is covered by the term pediatrics in childhood, to emphasize the necessity of considering senility and its disease apart from maturity and to assign it a separate place in medicine.” • Until Nascher’s time, older adults were not treated differently or in different ways than other adult patients. Social forces came into play in the period during WWI and WWII that both necessitated and facilitated long-term care for the elderly: The number of elderly people began to increase due to improvements in economic conditions and medicine. -

Evolutionism and Involutionism in the Ontogenesis of А Late

S662 25th European Congress of Psychiatry / European Psychiatry 41S (2017) S645–S709 EV0789 – Development of programs of psychological care to patients with Parkinson psychosis: A complex dementia and to caregivers; – Development of palliative care for patients with dementia; interaction of disease and medication – Cross-sectoral cooperation and multidisciplinary approach in related factors assistance to patients with dementia; 1,∗ 2 3 S. Petrykiv , L. de Jonge , M. Arts – Training in the field of geriatric psychiatry, denomination of the 1 University Medical Center Groningen, Department of Clinical specialty of geriatric psychiatrist; Pharmacy and Pharmacology, Groningen, The Netherlands – Fighting stigma of patients with dementia, protection of their 2 Leonardo Scientific Research Institute, Department of Geriatric rights, including in psychiatry and forensic psychiatry. Psychiatry, Department of Geriatric Psychiatry, Groningen, The The solution of these objectives requires foundation of the Rus- Netherlands sian observatory on dementia, the WHO cooperating center. The 3 University Medical Center Groningen, Department of Old Age tasks of such an Observatory will be: centralization and coordi- Psychiatry, Groningen, The Netherlands nation of actions concerning strategic planning, implementation of ∗ Corresponding author. mechanisms of a multispectral cooperation, assessment of services, Introduction Psychotic symptoms are the most important non- monitoring and providing reports on dementia issues in Russia. motoric symptoms of the Parkinson disease (PD). The quality of life Disclosure of interest The author has not supplied his/her decla- of those patients can be significantly improved with an appropri- ration of competing interest. ate therapy. In this article we provide evidence about the etiology, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2017.01.1120 differential diagnosis and therapeutic possibilities with a work-up for the clinics. -

Clinical Manual of Geriatric Psychopharmacology This Page Intentionally Left Blank Clinical Manual of Geriatric Psychopharmacology

Clinical Manual of Geriatric Psychopharmacology This page intentionally left blank Clinical Manual of Geriatric Psychopharmacology Sandra A. Jacobson, M.D. Assistant Professor, Department of Psychiatry and Human Behavior, Brown Medical School, Providence, Rhode Island Ronald W. Pies, M.D. Clinical Professor of Psychiatry, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston, Massachusetts Ira R. Katz, M.D. Professor of Psychiatry and Director, Section of Geriatric Psychiatry, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Washington, DC London, England Note: The authors have worked to ensure that all information in this book is accurate at the time of publication and consistent with general psychiatric and medical standards, and that information concerning drug dosages, schedules, and routes of administration is accurate at the time of publication and consistent with standards set by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and the general medical community. As medical research and practice continue to advance, however, therapeutic standards may change. Moreover, specific situations may require a specific therapeutic response not included in this book. For these reasons and because human and mechanical errors sometimes occur, we recommend that readers follow the advice of physicians directly involved in their care or the care of a member of their family. Books published by American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc., represent the views and opinions of the individual authors and do not necessarily represent the policies and opinions of APPI or the American Psychiatric Association. Copyright © 2007 American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED Manufactured in the United States of America on acid-free paper 11 10 09 08 07 5 4 3 2 1 First Edition Typeset in Adobe’s Formata and AGaramond. -

Table of Contents

2018 AAGP Annual Meeting TABLE OF CONTENTS Notes.............................................................................................................................................................. S2 Session .Abstracts General .Session.Abstract.Book. A Path Forward: A Culturally Relevant Psychosocial Intervention for Depression in Cognitive Impaired Older Adults ............................................................................................................................................. S3 AAGP Training Programs: Stepping Stones to the Scholars Program: Implications for Recruitment Into the Field of Geriatric Psychiatry ............................................................................................................................................. S4 Ethical, Legal and Forensic Issues in Geriatric Psychiatry ................................................................................................ S4 Global Brain Health Research: Collaborative Partnerships to Advance Care and Build Research Capacity ..................... S5 Innovative Approaches to Training the Next Generation of Geriatric Psychiatrists .......................................................... S6 Introduction to Agile Implementation Science: How to Select, Implement, Scale Up, and Sustain Evidence Based Geriatric Psychiatry Health Solutions ...................................................................................................................... S6 Sexuality and Religion in Older Adults: The Devil is in the Details -

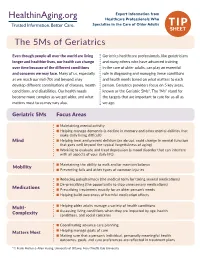

The 5Ms of Geriatrics

Expert Information from Healthcare Professionals Who Specialize in the Care of Older Adults TIP SHEET The 5Ms of Geriatrics Even though people all over the world are living Geriatrics healthcare professionals, like geriatricians longer and healthier lives, our health can change and many others who have advanced training over time because of the different conditions in the care of older adults, can play an essential and concerns we may face. Many of us, especially role in diagnosing and managing these conditions as we reach our mid-70s and beyond, may and health needs based on what matters to each develop different combinations of diseases, health person. Geriatrics providers focus on 5 key areas, conditions, and disabilities. Our health needs known as the Geriatric 5Ms*. The “Ms” stand for become more complex as we get older, and what the targets that are important to care for us all as matters most to us may vary also. we age. Geriatric 5Ms Focus Areas n Maintaining mental activity n Helping manage dementia (a decline in memory and other mental abilities that make daily living difficult) Mind n Helping treat and prevent delirium (an abrupt, rapid change in mental function that goes well beyond the typical forgetfulness of aging) n Working to evaluate and treat depression (a mood disorder that can interfere with all aspects of your daily life) n Maintaining the ability to walk and/or maintain balance Mobility n Preventing falls and other types of common injuries n Reducing polypharmacy (the medical term for taking several medications)