The Chad School Foundation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Community Engagement at Rutgers-Newark 2010–2012

BUILDING COMMUNITY TOGETHER! ututgersgersinin Newark Newark is oneone ofof three three campuses campuses of Rutgers,of Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey. Offering countless degrees The State University of New Jersey. Offering countless degrees through its undergraduate and graduate programs, it is home to the through its undergraduate and graduate programs, it is home to the Newark College of Arts and Sciences, University College, RNewark College of Arts and Sciences, UniversityCOMMUNITYCOMMUNITY College, ENGAGEMENTENGAGEMENT Rthe Graduate School-Newark, Rutgers Business School-Newark and New the Graduate School-Newark, Rutgers Business School-Newark and New Brunswick, the School of Law-Newark, the College of Nursing, the ATSchoolAT RUTGERS-NEWARKRUTGERS-NEWARK of Brunswick,Criminal the Justice, School the ofSchool Law-Newark, of Public Affairs the College and Administration, of Nursing, and the extensive School of Criminalresearch Justice, and outreach the School centers. of PublicMore than Affairs 11,000 and students Administration, are currently and enrolled extensive 2010–2012 researchin a wide and rangeoutreach of undergraduate centers. More and thangraduate 11,000 degree students programs are offered currently at the enrolled in a 35-acrewide range downtown of undergraduate Newark campus. and Rutgers-Newark graduate degree is rankedprograms among offered the leading at the urban research universities in the northeast, and number one for student diversity, 35-acre downtown Newark campus. Rutgers-Newark is ranked among the leading by U.S. News & World Report. urban research universities in the northeast, and number one for student diversity, by U.S.Rutgers News University & World celebrated Report. 100 years of higher education in the city of Newark in 2008. -

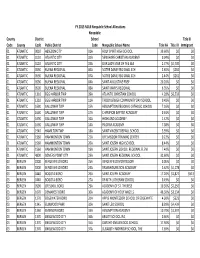

FY13 NCLB Nonpublic Allocation Tables

FY 2013 NCLB Nonpublic School Allocations Nonpublic County District School Title III Code County Code Public District Code Nonpublic School Name Title IIA Title III Immigrant 01 ATLANTIC 0010 ABSECON CITY 01A HOLY SPIRIT HIGH SCHOOL 39.60% $0 $0 01 ATLANTIC 0110 ATLANTIC CITY 02A NEW HOPE CHRISTIAN ACADEMY 0.04% $0 $0 01 ATLANTIC 0110 ATLANTIC CITY 03A OUR LADY STAR OF THE SEA 2.77% $4,700 $0 01 ATLANTIC 0590 BUENA REGIONAL 06A NOTRE DAME REGIONAL SCH 2.65% $262 $0 01 ATLANTIC 0590 BUENA REGIONAL 07A NOTRE DAME REGIONAL SCH 2.44% $261 $0 01 ATLANTIC 0590 BUENA REGIONAL 04A SAINT AUGUSTINE PREP 20.20% $0 $0 01 ATLANTIC 0590 BUENA REGIONAL 08A SAINT MARYS REGIONAL 6.35% $0 $0 01 ATLANTIC 1310 EGG HARBOR TWP 09A ATLANTIC CHRISTIAN SCHOOL 4.28% $6,533 $0 01 ATLANTIC 1310 EGG HARBOR TWP 11A TROCKI JEWISH COMMUNITY DAY SCHOOL 0.48% $0 $0 01 ATLANTIC 1690 GALLOWAY TWP 15A ASSUMPTION REGIONAL CATHOLIC SCHOOL 7.16% $0 $0 01 ATLANTIC 1690 GALLOWAY TWP 17A CHAMPION BAPTIST ACADEMY 0.91% $0 $0 01 ATLANTIC 1690 GALLOWAY TWP 16A HIGHLAND ACADEMY 1.42% $0 $0 01 ATLANTIC 1690 GALLOWAY TWP 14A PILGRIM ACADEMY 7.38% $0 $0 01 ATLANTIC 1940 HAMILTON TWP 18A SAINT VINCENT DEPAUL SCHOOL 5.39% $0 $0 01 ATLANTIC 1960 HAMMONTON TOWN 21A LIFE MISSION TRAINING CENTER 0.22% $0 $0 01 ATLANTIC 1960 HAMMONTON TOWN 20A SAINT JOSEPH HIGH SCHOOL 8. 44% $0 $0 01 ATLANTIC 1960 HAMMONTON TOWN 19A SAINT JOSEPH SCHOOL REGIONAL ELEM 7.40% $0 $0 01 ATLANTIC 4800 SOMERS POINT CITY 23A SAINT JOSEPH REGIONAL SCHOOL 32.60% $0 $0 03 BERGEN 0300 BERGENFIELD BORO 25A BERGENFIELD MONTESSORI 0.05% $0 $0 03 BERGEN 0300 BERGENFIELD BORO 24A TRANSFIGURATION ACADEMY 5.62% $4,178 $0 03 BERGEN 0440 BOGOTA BORO 26A SAINT JOSEPH ACADEMY 17.20% $1,827 $513 03 BERGEN 0440 BOGOTA BORO 27A TRINITY LUTHERAN SCHOOL 0.49% $0 $0 03 BERGEN 0990 CRESSKILL BORO 29A ACADEMY OF ST. -

The Newark Public Schools Historical Preservation Committee MISSION

The Newark Public Schools Historical Preservation Committee MISSION The Newark Public Schools Historical Preservation Committee is a 501 (c)(3) organization formed in 2009 to chronicle the district’s rich heritage by preserving its documents, artifacts and school buildings. It is our intention to share the history of the Newark Public Schools with students and the greater com- munity at a permanent historic site. This Distinguished Alumni Directory is the first in a series of publications that we hope will help to inform and instill a sense of pride in our Newark history. 1 NEWARK PUBLIC SCHOOLS DISTINGUISHED ALUMNI The Newark Public School District Historical Preservation Committee GOALS ≈ To establish a policy and guidelines for the preservation and archiving of historically valuable artifacts of the Newark Public Schools. ≈ To establish repositories within the schools for the col- lection and preservation of valuable documents and materials relating to the history of the school district which otherwise would be lost. ≈ To develop and keep current a chronology of significant events in the Newark Public Schools. ≈ To identify and nominate public schools for listing on the National Register of Historic Places. ≈ To establish a permanent Newark Public Schools museum. ≈ To have students become involved with the archiving and chronicling process. To develop collaborative work- ing relationships with alumni associations and other preservation organizations. 2 NEWARK PUBLIC SCHOOLS DISTINGUISHED ALUMNI JANET LIPPMAN ABU-LUGHOD (Weequahic/1945) (1928–2013) Urban sociologist; expert on the history and dynamics of the World System and Middle Eastern cities; taught for twenty years at Northeastern; retired in 1988 as professor of sociology and historical research on the Gradu- ate Faculty of the New School for Social Research; her thirteen books include the classic work: Cairo: 100 Years of the City Victorious. -

Cooperbaschdissertation.Pdf

THE EVOLUTION OF VICTORIA FOUNDATION FROM 1924 TO 2003 WITH A SPECIAL FOCUS ON THE NEWARK YEARS FROM 1964 TO 2003 by IRENE COOPER-BASCH A Dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-Newark Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey & New Jersey Institute of Technology in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Joint Graduate Program in Urban Systems-Education Policy Written under the direction of Dr. Alan R. Sadovnik, Rutgers University Chair and approved by _____________________________________________ Dr. Alan R. Sadovnik, Rutgers University _____________________________________________ Dr. Gabrielle Esperdy, New Jersey Institute of Technology _____________________________________________ Dr. Clement A. Price, Rutgers University _____________________________________________ Dr. Christopher J. Daggett, Geraldine R. Dodge Foundation, Morristown, NJ Newark, New Jersey May, 2014 © 2014 Irene Cooper-Basch ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION The Evolution of Victoria Foundation From 1924 to 2003 With a Special Focus on the Newark Years From 1964 to 2003 By IRENE COOPER-BASCH Dissertation Director: Professor Alan Sadovnik This dissertation examines the history of Victoria Foundation from its inception in 1924 through 2003, with a special emphasis on its place-based urban grantmaking in Newark, New Jersey from 1964 through 2003. Insights into Victoria’s role and impact in Newark, particularly those connected to its extensive preK-12 education grantmaking, were gleaned through an analyses of the evolution of Newark, the history of education in Newark, and the history of foundations in America. Several themes emerged from the research, an examination of the archives, and 28 oral history interviews including: charity vs. philanthropy, risk-taking, scattershot grantmaking, self-reflection, issues of race, and evaluation. -

MSA-CESS Spring 2016 Accreditation Actions the Middle States

Middle States Association of Colleges and Schools Commissions on Elementary and Secondary Schools 3624 Market Street, 2 West | Philadelphia, PA 19104-2680 Phone: 267-284-5000 | www.msa-cess.org MSA-CESS Spring 2016 Accreditation Actions The Middle States Association Commissions on Elementary and Secondary Schools announces that the following 100 schools and school systems in 11 states and Puerto Rico and 7 countries have earned accreditation or reaccreditation, the gold standard for measuring and evaluating school performance. Accreditation for Ten Years Accreditation for Seven Years (Continued) Holton-Arms School, Inc. (The), Bethesda, MD Escuela San German Interamericana, San German, Our Lady of Good Counsel High School, Olney, MD PR Wilmington Friends School, Wilmington, DE Faith Heritage School, Syracuse, NY Worcester Preparatory School, Berlin, MD Freehold Regional High School District, Englishtown, NJ Accreditation for Seven Years Colts Neck High School, Colts Neck, NJ Academia Discipulos de Cristo, Bayamon, PR Freehold High School, Freehold, NJ Academia San Ignacio de Loyola, San Juan, PR Freehold Township High School, Freehold, NJ Academy for Information Technology, Scotch Plains, Howell High School, Farmingdale, NJ NJ Manalapan High School, Englishtown, NJ Al Hekma International School, Kingdom of Bahrain Marlboro High School, Marlboro, NJ Ambatovy International School, Madagascar French American Academy, New Milford, NJ American Military Academy, Guaynabo, PR Gloucester Catholic High School, Gloucester, NJ American School of -

SLT I Action Plan

SLT I Action Plan SLT I is divided into SLT I Central (covering parts of the Central Ward and the East Ward west of McCarter Highway) and SLT I East (covering the Ironbound section). These are the parts of the city that were settled first and as such have many of the oldest schools, most in educationally obsolete facilities that are in poor condition. The cost to remedy program space deficiencies, which in many cases include restructuring classrooms sized less then 500 square feet, would exceed replacement costs and result in more gross square feet per student than new construction. Figure C.1 Most existing sites are too small to accept additions to provide the needed space, much less provide for recreation and parking. In many cases there EXISTING PROPOSED is no practical way to expand existing sites without major disruption to residential neighborhoods, and no space to relocate students while ENTIRE SLT buildings are under construction/renovation. (20) Buildings (12) Buildings Incl. (4) Annexes No Annexes Based on this analysis, most SLT I school buildings will be replaced as PK-8 schools based on a “house plan” configuration. The plan for SLT I includes eight new replacement schools, the existing East Side High building ELEMENTARY SCHOOLS renovated as a new PK-8 school, and the renovation and/or expansion of two (6) Buildings (0) Buildings existing schools. This plan is still consistent with the approved 2002 update. A Incl. (3) Early Childhood Centers summary of the existing and proposed use of each building is provided in Table C.2. -

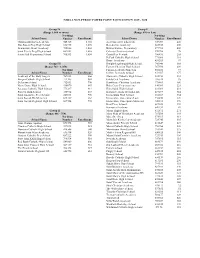

Njsiaa Non-Public Power Point Equivalency 2019 - 2020

NJSIAA NON-PUBLIC POWER POINT EQUIVALENCY 2019 - 2020 Group IV Group II (Range 1,060 or more) (Range 476 or less) Northing Northing School Name Number Enrollment School Name Number Enrollment Christian Brothers Academy 545325 1,386 Academy of St. Elizabeth 709053 240 Don Bosco Prep High School 814915 1,278 Benedictine Academy 665355 200 Immaculate Heart Academy 785846 1,062 Bishop Eustace Preparatory 399910 408 Saint Peter's Prep High School 683883 1,416 Calvary Christian School 570706 78 Seton Hall Preparatory School 705513 1,454 Cristo Rey Newark 700496 268 DePaul Catholic High School 771088 381 Doane Academy 451203 99 Group III Dwight-Englewood High School 745940 388 (Range 761 - 1,058) Eastern Christian High School 767500 280 Northing Fusion Academy Princeton 552400 37 School Name Number Enrollment Gill St. Bernard's School 652567 277 Academy of the Holy Angels 767833 866 Gloucester Catholic High School 385452 333 Bergen Catholic High School 771315 984 Golda Och Academy 705524 95 Delbarton School 712693 790 Hawthorne Christian Academy 778461 100 Notre Dame High School 516070 865 Holy Cross Prep Academy 446985 221 Paramus Catholic High School 771247 914 Holy Spirit High School 210019 281 Paul VI High School 388932 803 Hudson Catholic Regional HS 687497 364 Saint Augustine Prep School 243013 976 Immaculata High School 632567 354 Saint Joseph HS Metuchen 625289 862 Immaculate Conception Lodi 738459 320 Saint Joseph Regional High School 807704 772 Immaculate Conception Montclair 720111 170 Kent Place School 687222 396 Koinonia Academy -

School District Reform in Newark: Within- and Between-School Changes in Achievement Growth

SCHOOL DISTRICT REFORM IN NEWARK: WITHIN- AND BETWEEN-SCHOOL CHANGES IN ACHIEVEMENT GROWTH MARK CHIN, THOMAS J. KANE, WHITNEY KOZAKOWSKI, BETH E. SCHUELER, AND DOUGLAS O. STAIGER* In the 2011–12 school year, the Newark Public School district (NPS) launched a set of educational reforms supported by a gift from Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg and Priscilla Chan. Using data from 2008–09 through 2015–16, the authors evaluate the change in Newark students’ achievement growth relative to similar students and schools elsewhere in New Jersey. They measure achievement growth using a ‘‘value-added’’ model, controlling for prior achieve- ment, demographics, and peer characteristics. By the fifth year of reform, Newark saw statistically significant gains in English language arts (ELA) achievement growth and no significant change in math achievement growth. Perhaps because of the disruptive nature of the reforms, growth declined initially before rebounding in later years. Much of the improvement was attributed to shifting enrollment from lower- to higher-growth district and charter schools. n the fall of 2010, Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg, New Jersey I Governor Chris Christie, and Newark Mayor Corey Booker announced a school improvement effort in the Newark Public School district (NPS), to be aided by a $100 million gift from Zuckerberg and Priscilla Chan. This *MARK CHIN is a PhD Candidate at Harvard University. THOMAS J. KANE is the Walter H. Gale Professor of Education at Harvard University. WHITNEY KOZAKOWSKI is a PhD Candidate at Harvard University. BETH E. SCHUELER is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow at Harvard University. DOUGLAS O. STAIGER is a Professor at Dartmouth College. -

In Loving Memory 1

Coach Les Fein A Weequahic Legend Passes Within a span of five years in the 1960's, Les Fein's basketball teams won three state Group IV basketball championships and the 1967 squad was the best in the nation By Phil Yourish, 1964 I thought he was invincible. To a Weequahic guy who grew and his wife had with Weight And why not? After all, he was up in the bleachers of our tiny Watchers. the COACH. When I heard in gym watching the magical February that he had a heart moments of basketball unfold It needs to be noted that Les attack and a stroke, I believed, on the court before me, his was more than just sports and even at age 88, this would be stories about his teams and his basketball. He was a very just another challenge that he players were riveting - and he well-rounded individual with a would overcome. provided the emotion with the wide variety of interests who details. was an avid reader, enjoyed As the Executive Director of the music, art and theater, and was Weequahic High School As an ardent fan, the highlight very knowledgeable about local Alumni Association, I got to of my high school years was the and world affairs. know Les Fein over the recent Weequahic basketball team. years in a way that I never knew Could there be a finer moment Recently, he sent me an article him when he was my physical than when Weequahic beat that he wrote and wanted me to and health education teacher at Westfield to capture its first critique. -

Commemorative Clarion 50Th

NEW COMMUNITY CORPORATION Commemorative Clarion th 50ANNIVERSARY 1968 – 2018 OUT OF THE ASHES Serving The People Of The New Community Network CAME HOPE Volume 35 — Issue 7 ~ July 2018 Honoring The Life And Legacy Of New Community Founder Monsignor William J. Linder onsignor William J. Linder lived a life of service, helping to Court, which provided better the lives of countless individuals during his time on family housing, opened Mearth. Many of those people gathered to pay tribute to him in 1975. Construction on after his passing June 8 at the age of 82. the most recent, A Better Life, a supportive housing facility for chronically Monsignor served others as a priest following his ordination in 1963. homeless individuals that Monsignor envisioned, was completed in 2017. Five years later, he founded New Community Corporation, which has In between, Monsignor oversaw the creation of numerous housing facilities served inner-city residents for 50 years and continues to provide critical for seniors and families in Newark, Englewood, Jersey City and Orange. services like housing, job training, health care and child care. He was also at the helm of NCC when it opened the New Community Those who knew him say he fought to get what was needed for Federal Credit Union in 1984, took on the renovations at St. Joseph Plaza community members and helped others without expecting anything in in 1985 and opened the nursing home, New Community Extended Care, return. in 1986. New Community CEO Richard Rohrman said Monsignor was very Harmony House, New Community’s transitional housing facility hands-on in his approach. -

New Jersey Catholic Records Newsletter, Vol. 13, No.3 New Jersey Catholic Historical Commission

Seton Hall University eRepository @ Seton Hall New Jersey Catholic Historical Commission Archives and Special Collections newsletters Spring 1994 New Jersey Catholic Records Newsletter, Vol. 13, No.3 New Jersey Catholic Historical Commission Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.shu.edu/njchc Part of the History Commons, and the Religion Commons Recommended Citation New Jersey Catholic Historical Commission, "New Jersey Catholic Records Newsletter, Vol. 13, No.3" (1994). New Jersey Catholic Historical Commission newsletters. 36. https://scholarship.shu.edu/njchc/36 NEW JERSEY faJJwIic J-li£lorlml RECORDS COMMISSION Sl TON HAll UNIVE RSI TY VOLUME XIII NO.3 SPRING 1994 .Joseph Michael Flynn's Legacy Is a Wealth of Early Church History For 90 years now the first source to company. Three years later, in May1864, which people have turned for the history he enlisted in Company B, 37th New of Catholics in New Jersey before 1900 Jersey Volunteers and was mustered into has been "Flynn," Le., The Catholic federal service for a period of 100 days Church in New Jersey by Monsignor on June 22. The Thirty-Seventh, under Joseph M. Flynn, published at the command of Colonel E. Burd Grubb, Morristown in 1904. Since Flynn was spent its active duty in the entrenchments .not a historian by training, that may seem before Richmond and Petersburg and, somewhat strange. although it engaged in no formal battles, Joseph M. Flynn was born on lost five killed in action, 29 wounded in January 7,1848 in Springfield, Massa action and 13 others to illness. Flynn was chusetts. His family moved to New York promoted to corporal in July, and City, where he attended St. -

Super Essex Conference 2014 School Location Mascot Athletic Director Athletic Trainer

Super Essex Conference 2014 School Location Mascot Athletic Director Athletic Trainer 1 Arts High School Newark Jaguars 2 Barringer High School Newark Blue Bears 3 Belleville High School Belleville Buccaneers 4 Bloomfield High School Bloomfield Bengals 5 Bloomfield Tech High School Bloomfield Spartans 6 Cedar Grove High School Cedar Grove Panthers 7 Central High School Newark Blue Devils 8 Christ the King Newark Knights 9 Columbia High School Maplewood Cougars 10 East Orange Campus High School East Orange Jaguars 11 East Side High School Newark Red Raiders 12 Glen Ridge High School Glen Ridge Ridgers 13 Golda Och Academy West Orange Roadrunners 14 Immaculate Conception High School Montclair Lions 15 Irvington High School Irvington Blue Knights 16 James Caldwell High School West Caldwell Chiefs 17 Livingston High School Livingston Lancers 18 Malcolm X Shabazz High School Newark Bulldogs 19 Millburn High School Millburn Millers 20 Montclair High School Montclair Mounties 21 Montclair Kimberley Academy Montclair Cougars 22 Mount Saint Dominic Academy Caldwell Lady Lions 23 Newark Academy Livingston Minutemen 24 Newark Tech Newark Terriers 25 North 13th St Tech Newark Cougars 26 Nutley High School Nutley Maroon Raiders 27 Orange High School Orange Tornadoes 28 Saint Vincent Academy Newark Panthers 29 Science Park High School Newark Chargers 30 Seton Hall Prep West Orange Pirates 31 Technology High School Newark Panthers 32 University High School Newark Phoenix 33 Verona High School Verona Hillbillies 34 Weequahic High School Newark Indians Super Essex Conference 2014 School Location Mascot Athletic Director Athletic Trainer 35 West Essex High School North Caldwell Knights 36 West Orange High School West Orange Mountaineers 37 West Side High School Newark Roughriders Super Essex Conference 2014 phone number email Super Essex Conference 2014 phone number email.