Digital Skills Crisis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parker Review

Ethnic Diversity Enriching Business Leadership An update report from The Parker Review Sir John Parker The Parker Review Committee 5 February 2020 Principal Sponsor Members of the Steering Committee Chair: Sir John Parker GBE, FREng Co-Chair: David Tyler Contents Members: Dr Doyin Atewologun Sanjay Bhandari Helen Mahy CBE Foreword by Sir John Parker 2 Sir Kenneth Olisa OBE Foreword by the Secretary of State 6 Trevor Phillips OBE Message from EY 8 Tom Shropshire Vision and Mission Statement 10 Yvonne Thompson CBE Professor Susan Vinnicombe CBE Current Profile of FTSE 350 Boards 14 Matthew Percival FRC/Cranfield Research on Ethnic Diversity Reporting 36 Arun Batra OBE Parker Review Recommendations 58 Bilal Raja Kirstie Wright Company Success Stories 62 Closing Word from Sir Jon Thompson 65 Observers Biographies 66 Sanu de Lima, Itiola Durojaiye, Katie Leinweber Appendix — The Directors’ Resource Toolkit 72 Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy Thanks to our contributors during the year and to this report Oliver Cover Alex Diggins Neil Golborne Orla Pettigrew Sonam Patel Zaheer Ahmad MBE Rachel Sadka Simon Feeke Key advisors and contributors to this report: Simon Manterfield Dr Manjari Prashar Dr Fatima Tresh Latika Shah ® At the heart of our success lies the performance 2. Recognising the changes and growing talent of our many great companies, many of them listed pool of ethnically diverse candidates in our in the FTSE 100 and FTSE 250. There is no doubt home and overseas markets which will influence that one reason we have been able to punch recruitment patterns for years to come above our weight as a medium-sized country is the talent and inventiveness of our business leaders Whilst we have made great strides in bringing and our skilled people. -

The Big Recruitment Fair Programme

E D G E H I L L U N I V E R S I T Y & C A R E E R S A R E H O S T I N G . THE BIG RECRUITMENT FAIR 2018 TUESDAY 16TH OCTOBER 2018 Hale Hall & The Hub 11AM TO 3.00PM Event Programme Go to https://careerhub.edgehill.ac.uk/ for more details Contents Access Point p.6 Active Soccer p.7 Agrial Fresh Produce Ltd p.8 (Saladstogo) p.9 Airborne Environmental Consultants p.10 AO.Com p.11 Barclays p.12 Barron Wood Distribution Ltd p.13 Beat Eating Disorders p.14 Beth Tweddle Gymnastics p.15 boohoo.com p.16 Carpenters Solicitors p.17 Civil Nuclear Constabulary p.18 ComMutual p.19 DC Law p.20 Doris IT p.21 Edge Hill University - Careers p.22 Edge Hill University - Postgraduate Study p.23 Edge Hill University - Scholarships p.24 EKM p.25 Enterprise Rent-A-Car p.26 Ernst & Young LLP (EY) p.27 Eurofins Agroscience Services p.28 Explore Learning p.29 EY Riverview Law p.30 Farmfoods p.31 FDM Group p.32 Fletchers p.33 HMRC p.34 Immersive Interactive Ltd p.35 JD Sports Fashion PLC p.36 Lancashire Police p.37 Mando Agency p.38 Matalan p.39 MDS Global p.40 Merseyside Police Special Constabulary p.41 Milexa Group p.42 Mint Casting Agency p.43 Mitie - Care + Custody p.44 Moneysupermarket Group p.45 MyCSP p.46 National Probation Service p.47 N Brown p.48 NHS Leadership Academy p.49 Nublue p.50 Pure Business Group Ltd p.51 QVC p.52 Roar Software p.53 ROQ p.54 Royal Air Force p.55 Slater and Gordon Group p.56 Stephensons Solicitors LLP p.57 The Sovini Group p.58 Transitional Rehabilitation Units (TRU) Ltd p.59 UKFast p.60 UK Visas and Immigration - Home Office p.61 Wigan Youth Zone P.62 Access Point Access Point is based in Southport and is a privately owned local business that has national coverage. -

FTSE Russell Publications

2 FTSE Russell Publications 19 August 2021 FTSE 250 Indicative Index Weight Data as at Closing on 30 June 2021 Index weight Index weight Index weight Constituent Country Constituent Country Constituent Country (%) (%) (%) 3i Infrastructure 0.43 UNITED Bytes Technology Group 0.23 UNITED Edinburgh Investment Trust 0.25 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM 4imprint Group 0.18 UNITED C&C Group 0.23 UNITED Edinburgh Worldwide Inv Tst 0.35 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM 888 Holdings 0.25 UNITED Cairn Energy 0.17 UNITED Electrocomponents 1.18 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM Aberforth Smaller Companies Tst 0.33 UNITED Caledonia Investments 0.25 UNITED Elementis 0.21 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM Aggreko 0.51 UNITED Capita 0.15 UNITED Energean 0.21 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM Airtel Africa 0.19 UNITED Capital & Counties Properties 0.29 UNITED Essentra 0.23 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM AJ Bell 0.31 UNITED Carnival 0.54 UNITED Euromoney Institutional Investor 0.26 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM Alliance Trust 0.77 UNITED Centamin 0.27 UNITED European Opportunities Trust 0.19 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM Allianz Technology Trust 0.31 UNITED Centrica 0.74 UNITED F&C Investment Trust 1.1 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM AO World 0.18 UNITED Chemring Group 0.2 UNITED FDM Group Holdings 0.21 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM Apax Global Alpha 0.17 UNITED Chrysalis Investments 0.33 UNITED Ferrexpo 0.3 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM Ascential 0.4 UNITED Cineworld Group 0.19 UNITED Fidelity China Special Situations 0.35 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM Ashmore -

Connect to Your Future Success Information Technology, Science and Engineering Fair 2015 Contents

Connect to your future success Information Technology, Science and Engineering Fair 2015 Contents 3 Introduction 12–23 Exhibitor Profiles 4 Prepare for the Fair, CV Clinic and 24–25 Stand Plan Jobs Board 26–27 Exhibitors by Stand Number 5 Visa Information 28–44 Exhibitor Profiles 6 Information for Alumni 46 What Next? 9 Welcome from our Sponsors 47 Contact Information 11 Sponsor Profiles Further information For more information on the opportunities exhibitors are offering, please see the Exhibitor Profiles 2 The Careers and Employability Service is committed to offering the best possible opportunities to our students and, to that end, we have more exhibiting organisations attending than ever before. From sectors as diverse as engineering and IT to retail and financial services, there will be a wide range of exhibiting organisations for you to connect with. The Fair is an excellent opportunity for you to market yourself to your chosen industry, explore what roles and opportunities are available, and to build useful contacts for future reference. You will also be able to seek advice from the Careers and Employability Service and get tips on writing your CV at our graduate recruiter led CV Clinics – all available on the day. The Careers and Employability staff look forward to meeting you at the Fair. Please visit stand 11. We would like to take this opportunity to thank the following companies for sponsoring our Information Technology, Science and Engineering Fair: Key Use this to see at a glance the opportunities the exhibiting employers are offering. Check individual employer websites for more details. -

Equity Suggestions

January 2020 Equity Suggestions Price 52 Week FTSE 100 COMPANIES 1/1/20 Yield High Low BEVERAGES Diageo PLC Ordinary Shares 3201p 2.1% 3634p 2689p CHEMICALS Croda International PLC Ordinary Shares 5120p 1.7% 5415p 4510p FINANCIAL SERVICES Schroders PLC Voting Shares 3334p 3.4% 3456p 2390p FOOD PRODUCERS Unilever PLC Ordinary Shares 4351p 3.3% 5333p 3905p FORESTRY & PAPER DS Smith PLC Ordinary Shares 384p 4.2% 398p 292p Smurfit Kappa Group PLC Ordinary Shares 2920p 3.0% 2976p 2028p HEALTHCARE PRODUCTS Smith & Nephew PLC Ordinary Shares 1833p 1.5% 1998p 1383p INDUSTRIALS Halma PLC Ordinary Shares 2116p 0.8% 2195p 1308p Spirax-Sarcro Engineering PLC Ord Shares 8890p 1.1% 9440p 5935p LIFE INSURANCE Prudential PLC Ordinary Shares 1449p 3.4% 1539p 1114p MEDIA RELX PLC Ordinary Shares 1906p 2.3% 2027p 1571p MINING BHP Group PLC Ordinary Shares 1777p 5.8% 2079p 1504p Rio Tinto PLC Ordinary Shares 4503p 5.7% 4977p 3393p OIL & GAS BP PLC Ordinary Shares 472p 6.5% 583p 461p Royal Dutch Shell B PLC Ordinary Shares 2240p 6.5% 2647p 2124p NONLIFE INSURANCE Admiral Group PLC Ordinary Shares 2309p 5.4% 2332p 1935p SUPPORT SERVICES DCC PLC Ordinary Shares 6544p 2.2% 7548p 5845p Experian PLC Ordinary Shares 2552p 1.4% 2641p 1800p Intertek PLC Ordinary Shares 5858p 1.7% 5982p 4583p TECHNOLOGY Rightmove PLC Ordinary Shares 634p 1.1% 677p 427p TRAVEL & LEISURE Carnival PLC Ordinary Shares 3644p 4.3% 4448p 3037p Compass Group PLC Ordinary Shares 1890p 2.1% 2150p 1576p UTILITIES National Grid PLC Ordinary Shares 944p 5.0% 970p 746p Severn Trent PLC Ordinary -

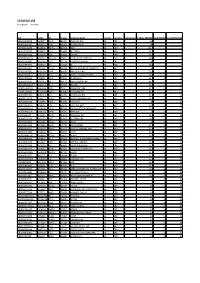

STOXX UK 180 Selection List

STOXX UK 180 Last Updated: 20210301 ISIN Sedol RIC Int.Key Company Name Country Currency Component FF Mcap (BEUR) Rank (FINAL)Rank (PREVIOUS) GB00B10RZP78 B10RZP7 ULVR.L 091321 UNILEVER PLC GB GBP Y 113 1 1 GB0009895292 0989529 AZN.L 098952 ASTRAZENECA GB GBP Y 105 2 2 GB0005405286 0540528 HSBA.L 040054 HSBC GB GBP Y 101.6 3 3 GB0007188757 0718875 RIO.L 071887 RIO TINTO GB GBP Y 76.5 4 7 GB0002374006 0237400 DGE.L 039600 DIAGEO GB GBP Y 75.8 5 4 GB00B03MLX29 B09CBL4 RDSa.AS B09CBL ROYAL DUTCH SHELL A GB EUR Y 69.3 6 8 GB0009252882 0925288 GSK.L 037178 GLAXOSMITHKLINE GB GBP Y 69 7 5 GB0007980591 0798059 BP.L 013849 BP GB GBP Y 68.3 8 9 GB0002875804 0287580 BATS.L 028758 BRITISH AMERICAN TOBACCO GB GBP Y 62 9 6 GB00BH0P3Z91 BH0P3Z9 BHPB.L 005666 BHP GROUP PLC. GB GBP Y 55.2 10 11 GB00B24CGK77 B24CGK7 RB.L 072769 RECKITT BENCKISER GRP GB GBP Y 50.9 11 10 GB0007099541 0709954 PRU.L 070995 PRUDENTIAL GB GBP Y 42.3 12 14 GB00B1XZS820 B1XZS82 AAL.L 490151 ANGLO AMERICAN GB GBP Y 40.5 13 15 GB00B2B0DG97 B2B0DG9 REL.L 073087 RELX PLC GB GBP Y 38.6 14 12 GB00BH4HKS39 BH4HKS3 VOD.L 071921 VODAFONE GRP GB GBP Y 37.7 15 13 JE00B4T3BW64 B4T3BW6 GLEN.L GB10B3 GLENCORE PLC GB GBP Y 36.5 16 18 GB00BDR05C01 BDR05C0 NG.L 024282 NATIONAL GRID GB GBP Y 32.7 17 16 GB0008706128 0870612 LLOY.L 087061 LLOYDS BANKING GRP GB GBP Y 31.8 18 22 GB0031348658 3134865 BARC.L 007820 BARCLAYS GB GBP Y 30 19 23 GB00BD6K4575 BD6K457 CPG.L 053315 COMPASS GRP GB GBP Y 29.9 20 21 GB00B0SWJX34 B0SWJX3 LSEG.L 095298 LONDON STOCK EXCHANGE GB GBP Y 25.2 21 17 GB00B19NLV48 B19NLV4 -

Premium Listed Companies Are Subject to the UK's Super-Equivalent Rules Which Are Higher Than the EU Minimum "Standard Listing" Requirements

List of Premium Equity Comercial Companies - 29th April 2020 Definition: Premium listed companies are subject to the UK's super-equivalent rules which are higher than the EU minimum "standard listing" requirements. Company Name Country of Inc. Description of Listed Security Listing Category Market Status Trading Venue Home Member State ISIN(S) 4IMPRINT GROUP PLC United Kingdom Ordinary Shares of 38 6/13p each; fully paid Premium Equity Commercial Companies RM LSE United Kingdom GB0006640972 888 Holdings Plc Gibraltar Ordinary Shares of 0.5p each; fully paid Premium Equity Commercial Companies RM LSE United Kingdom GI000A0F6407 AA plc United Kingdom Ordinary Shares of 0.1p each; fully paid Premium Equity Commercial Companies RM LSE United Kingdom GB00BMSKPJ95 Admiral Group PLC United Kingdom Ordinary Shares of 0.1p each; fully paid Premium Equity Commercial Companies RM LSE United Kingdom GB00B02J6398 AGGREKO PLC United Kingdom Ordinary Shares of 4 329/395p each; fully paid Premium Equity Commercial Companies RM LSE United Kingdom GB00BK1PTB77 AIB Group Plc Ireland Ordinary Shares of EUR0.625 each; fully paid Premium Equity Commercial Companies RM LSE Ireland IE00BF0L3536 Air Partner PLC United Kingdom Ordinary Shares of 1p each; fully paid Premium Equity Commercial Companies RM LSE United Kingdom GB00BD736828 Airtel Africa plc United Kingdom Ordinary Shares of USD0.50 each; fully paid Premium Equity Commercial Companies RM LSE United Kingdom GB00BKDRYJ47 AJ Bell plc United Kingdom Ordinary Shares of GBP0.000125 each; fully paid Premium -

FTSE Russell Publications

FTSE Russell Publications 19 November 2018 FTSE 250 Indicative Index Weight Data as at Closing on 28 September 2018 Index weight Index weight Index weight Constituent Country Constituent Country Constituent Country (%) (%) (%) 3i Infrastructure 0.34 UNITED Capital & Counties Properties 0.51 UNITED Esure Group 0.21 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM 888 Holdings 0.13 UNITED Card Factory 0.16 UNITED Euromoney Institutional Investor 0.19 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM AA 0.15 UNITED Centamin 0.3 UNITED F&C Commercial Property Trust 0.19 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM Aberforth Smaller Companies Tst 0.32 UNITED Charter Court Financial Services Group 0.12 UNITED F&C Global Smaller Companies 0.22 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM Aggreko 0.54 UNITED Cineworld Group 0.82 UNITED FDM Group Holdings 0.21 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM Alliance Trust 0.68 UNITED City of London Investment Trust 0.39 UNITED Ferrexpo 0.15 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM Amigo Holdings 0.09 UNITED Clarkson 0.17 UNITED Fidelity China Special Situations 0.21 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM Ascential 0.43 UNITED Close Brothers Group 0.62 UNITED Fidelity European Values 0.25 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM Ashmore Group 0.36 UNITED CLS Holdings 0.09 UNITED Fidelity Special Values 0.13 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM Assura 0.33 UNITED Coats Group 0.3 UNITED Finsbury Growth & Income Trust 0.36 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM Auto Trader Group 1.07 UNITED Cobham 0.72 UNITED FirstGroup 0.29 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM Avast 0.18 UNITED Computacenter 0.23 UNITED Fisher (James) & Sons -

FTSE Factsheet

FTSE COMPANY REPORT Share price analysis relative to sector and index performance eEnergy Group PLC EAAS Industrial Support Services — GBP 0.23 at close 18 June 2021 Absolute Relative to FTSE UK All-Share Sector Relative to FTSE UK All-Share Index PERFORMANCE 18-Jun-2021 18-Jun-2021 18-Jun-2021 0.3 350 400 1D WTD MTD YTD Absolute 0.0 2.2 -4.2 95.7 350 300 Rel.Sector 1.3 2.1 -4.4 77.4 0.25 Rel.Market 1.7 3.9 -3.8 79.7 300 250 0.2 VALUATION 250 200 Trailing 200 Relative Price Relative 0.15 Price Relative 150 PE -ve Absolute Price (local (local currency) AbsolutePrice 150 EV/EBITDA -ve 0.1 100 100 PB -ve PCF -ve 0.05 50 50 Div Yield 0.0 Jun-2020 Sep-2020 Dec-2020 Mar-2021 Jun-2021 Jun-2020 Sep-2020 Dec-2020 Mar-2021 Jun-2021 Jun-2020 Sep-2020 Dec-2020 Mar-2021 Jun-2021 Price/Sales - Absolute Price 4-wk mov.avg. 13-wk mov.avg. Relative Price 4-wk mov.avg. 13-wk mov.avg. Relative Price 4-wk mov.avg. 13-wk mov.avg. Net Debt/Equity - 100 100 100 Div Payout 0.0 90 90 90 ROE - 80 80 80 70 70 Index) Share Share Sector) Share - - 70 60 60 DESCRIPTION 60 50 50 50 The Company principal activities are the At eEnergy 40 40 RSI RSI (Absolute) 40 our focus is helping schools and businesses to 30 30 reduce their energy consumption through "Energy 20 20 30 Efficiency as a Service"• (EEaaS). -

Companies That Have Either Cut, Cancelled Or Postponed Dividends This Year

COMPANIES THAT HAVE EITHER CUT, CANCELLED OR POSTPONED DIVIDENDS THIS YEAR 1pm Clarkson Hunting Morgan Sindall ScS 4imprint Close Brothers Hydrogen Morses Club Secure Trust Bank AA Coats Hyve Mortgage Advice Senior Bureau Abbey Colefax Ibstock Shaftesbury Mpac AdEPT Technology Costain IMI Shoe Zone N Brown Adnams Crest Nicholson Ince SIG NewRiver Reit AG Barr Dalata Hotels Inchcape Signature Aviation Next Fifteen Aggreko DFS Furniture Inland Homes Smiths Group Nichols Alliance Pharma Dignity InterContinental Hotels Softcat Non-Standard Alpha FX Direct Line International Somero Enterprises Finance Consolidated Airlines Alumasc Domino's Pizza Spectris Norish International Amedeo Air Four Plus DP Group Springfield Personal Finance Nucleus Financial Properties Amino DS Smith INTU Ocean Wilsons Technologies SSP Group Dunelm ITV OneSavings Bank Anexo St Modwen Elecosoft IWG On The Beach Properties Animalcare Elementis James Cropper Oxford Instruments Stagecoach Applegreen Empiric Student James Fisher Palace Capital Standard Chartered Appreciate Properties James Halstead Page Group SThree Aquila Services Epwin JD Wetherspoon Persimmon STV Arbuthnot Banking Essentra John Menzies Petrofac Synectics Arrow Global FDM Group Johnson Service Photo-Me Taylor Wimpey ASA International FIH International K3 BusinessTech The Works Ascential Filta Playtech Keystone Law Topps Tiles Avation FinnCap Polypipe Kin & Carta Tracsis Aviva Finsbury Foods Portmieirion Kingfisher Travis Perkins BAE Systems Flowtech Fluidpower PPHE Hotel Land Securities Tribal Bakkavor -

Morningstar® UK Dividend Yield Focus Indexsm 18 June 2021

Morningstar Indexes | Reconstitution Report Page 1 of 3 Morningstar® UK Dividend Yield Focus IndexSM 18 June 2021 The Morningstar® UK Dividend Yield Focus IndexSM is part of the Morningstar® Global Dividend Yield Focus Index Family. The index tracks the For More Information: performance of a portfolio of high-quality, dividend-paying securities. The constituents of the index are a subset of the Morningstar® UK Index http://indexes.morningstar.com (benchmark), a broad market index representing 97% of UK's equity market capitalization. US: +1 312 384-3735 Europe: +44 20 3194 1082 Reconstituted Holdings Name Ticker Country Sector Yield(%) Weight(%) Unilever ULVR United Kingdom Consumer Defensive 3.53 10.00 Royal Dutch Shell PLC RDSA United Kingdom Energy 3.63 9.37 Reckitt Benckiser Group PLC RKT United Kingdom Consumer Defensive 2.74 9.09 RELX Plc REL United Kingdom Communication Services 2.56 8.99 Mondi Plc MNDI United Kingdom Basic Materials 4.23 8.79 3I Group III United Kingdom Financial Services 2.82 7.58 Severn Trent SVT United Kingdom Utilities 4.14 5.82 Polymetal International PLC POLY United Kingdom Basic Materials 5.56 5.71 IG Group Holdings IGG United Kingdom Financial Services 5.04 3.66 Pearson PSON United Kingdom Communication Services 2.38 3.52 Schroders Plc SDR United Kingdom Financial Services 3.20 3.29 Renewables Infrastructure Group TRIG United Kingdom Financial Services 5.26 3.27 Man Group EMG United Kingdom Financial Services 4.38 2.92 Plus500 Ltd PLUS United Kingdom Financial Services 7.32 2.52 Hargreaves Lansdown Plc HL. -

January Illuminator Update Last Month the Illuminator Has Outperformed

January Illuminator update The Illuminator is a proprietary database and stock selection tool that identifies high-quality companies based on 10 characteristics. We have now published The Illuminator for over ten years. We adhere to the fundamental premise that, over the medium to long term, quality companies outperform the market. Since its inception in July 2008, the Illuminator has returned more than 1,000% compared to the UK All Share index return of 129% over the same period. Last month the Illuminator has outperformed the broader market by 2.2%. In the four weeks to 13 January 2020, the main Illuminator screen of 10 stocks gained 5.5% compared to a 3.3% increase in the UK All Share index. Since the beginning of the year, the Illuminator has slightly underperformed the overall market, having delivered a relative outperformance of 971% since its inception. Since our last update in December 2019, there was one change in the list of the top 10 names that make up the Illuminator, with Avon Rubber replacing Plus500. Illuminator performance: Cumulative returns Year to Three Since One month Six months One year Three years date months inception Illuminator UK 0.42% 5.51% 19.34% 20.77% 58.26% 72.05% 1100.00% UK All Share 0.72% 3.30% 6.55% 5.22% 16.13% 19.77% 128.75% Illuminator relative -0.30% 2.21% 12.79% 15.55% 42.13% 52.28% 971.25% Top 10 Illuminator Stocks Market cap Company Ticker Sector (£m) Free float, % YTD, % Coats Group COA Divers. Industrials 1107 99.8 5 4Imprint Group FOUR Media Agencies 932 98.2 -3 Rightmove RMV Consumer Digital Svs 5665 99.5 3 Fdm Group FDM Computer Services 1120 80.1 -4 Gamma Communications GAMA Telecom.