Statement of Basis, Purpose, Specific Statutory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

April 16, 2015 Dear Legislator: Attached You Will Find a Petition

April 16, 2015 Dear Legislator: Attached you will find a petition, signed by over 3,100 Coloradans from over 200 communities, asking you to do whatever you can to ensure that Colorado’s students benefit from our state’s nation-leading economic recovery. You will also find 600 comments and stories, conveying the impact that inadequate education funding is having on schools in Colorado – including those in your district. Please note, for your convenience the signatures are organized by city. The Coloradoans who have signed this petition seek to convey to you the urgent need to repay the debt we owe our students after years of budget cuts. They seek to remind you that there are still decisions that the legislature could make during this legislative session to increase education funding this year and for years to come. The decisions you make – or that you fail to make – in the next four weeks will have a profound impact on the quality of education available to every student in Colorado. We hope you will carefully consider the words, stories and comments attached to this letter as you help determine Colorado’s moral and fiscal path. Thank you for your service and for your attention to the future our children, our state and our economy. To: Governor Hickenlooper and Members of the 70th General Assembly: We are parents, grandparents, educators, businesspeople and community members who have a simple message for you now that Colorado’s rebounding economy is producing revenues above the TABOR limit. Keep the surplus for kids. In bad economic times, Colorado’s kids suffered well over $1 billion in cuts to education. -

Pipefitters PEC Endorsed Candidates 2020 Federal Races CU Regents

Pipefitters PEC Endorsed Candidates 2020 Federal Races John W. Hickenlooper - US Senator Joe Neguse - US House District 02 Jason Crow - US House District 06 Ed Perlmutter - US House District 07 CU Regents Ilana Spiegel - CU Regent District 06 Colorado State Senate Joann Ginal - State Senate District 14 Sonya Jaquez Lewis - State Senate District 17 Steve Finberg - State Senate District 18 Rachel Zenzinger - State Senate District 19 Jeff Bridges - State Senate District 26 Chris Kolker - State Senate District 27 Janet Buckner - State Senate District 28 Rhonda Fields - State Senate District 29 Colorado State House Susan Lontine - State House District 01 Alec Garnett - State House District 02 Meg Froelich - State House District 03 Serena Gonzales-Gutierrez - State House District 04 Alex Valdez - State House District 05 Dan Himelspach - State House District 6 Leslie Herod - State House District 08 Emily Sirota - State House District 09 Edie Hooton - State House District 10 Karen McCormick - State House District 11 Judy Amabile – State House District 13 Colorado State House – Con’t Chris Kennedy – State House District 23 Monica Duran - State House District 24 Lisa A. Cutter - State House District 25 Brianna Titone - State House District 27 Kerry Tipper - State House District 28 Lindsey N. Daugherty - State House District 29 Dafna Michaelson Jenet - State House District 30 Yadira Caraveo - State House District 31 Matt Gray - State House District 33 Kyle Mullica - State House District 34 Shannon Bird - State House District 35 Mike Weissman - State House District 36 Tom Sullivan - State House District 37 David Ortiz - State House District 38 John Ronquillo – State House District 40 Dominique Jackson - State House District 42 Mary Young - State House District 50 Jeni Arndt - State House District 53 District Attorneys Jake Lilly - District Attorney Judicial District 01 Brian Mason - District Attorney Judicial District 17 Amy L. -

The Arc of Colorado 2019 Legislative Scorecard

The Arc of Colorado 2019 Legislative Scorecard A Letter from Our Executive Director: Dear Members of The Arc Community, Once again, I would like to thank each of you for your part in a successful legislative session. We rely on your expertise in the field. We rely on you for our strength in numbers. For all the ways you contributed this session, we are deeply appreciative. I would like to give a special thanks to those that came and testified on our behalf; Stephanie Garcia, Carol Meredith, Linda Skafflen, Shelby Lowery, Vicki Wray, Rowan Frederiksen, and many others who I may not have mentioned here. This session was a historic one. For the first time in 75 years, one party had control of the house, senate, and governor’s office. Additionally, there were 43 new legislators! We enjoyed a productive year in which The Arc of Colorado monitored 100 bills. Of those that we supported, 92% were signed by the governor and 100% of the bills that we opposed died. This high success rate means that individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities and their families will have more opportunity to better live, work, learn, and play in their Colorado communities, with increased support. We are excited about many of this year’s outcomes. In a very tight budget year, the Joint Budget Committee was able to free up money for 150 additional slots for the Developmental Disabilities waiver waitlist. After three years of involvement, we finally saw the passing of HB19-1194, which places restrictions on suspensions and expulsions of children from preschool, through to second grade. -

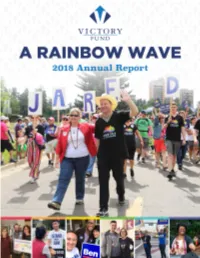

2018 Annual Report | 1 “From the U.S

A Rainbow Wave: 2018 Annual Report | 1 “From the U.S. Congress to statewide offices to state legislatures and city councils, on Election Night we made historic inroads and grew our political power in ways unimaginable even a few years ago.” MAYOR ANNISE PARKER, PRESIDENT & CEO LGBTQ VICTORY FUND BOARD OF DIRECTORS Chris Abele, Chair Michael Grover Richard Holt, Vice Chair Kim Hoover Mattheus Stephens, Secretary Chrys Lemon Campbell Spencer, Treasurer Stephen Macias Stuart Appelbaum Christopher Massicotte (ex-officio) Susan Atkins Daniel Penchina Sue Burnside (ex-officio) Vince Pryor Sharon Callahan-Miller Wade Rakes Pia Carusone ONE VICTORY BOARD OF DIRECTORS LGBTQ VICTORY FUND CAMPAIGN BOARD LEADERSHIP Richard Holt, Chair Chris Abele, Vice Chair Sue Burnside, Co-Chair John Tedstrom, Vice Chair Chris Massicotte, Co-Chair Claire Lucas, Treasurer Jim Schmidt, Endorsement Chair Campbell Spencer, Secretary John Arrowood LGBTQ VICTORY FUND STAFF Mayor Annise Parker, President & CEO Sarah LeDonne, Digital Marketing Manager Andre Adeyemi, Executive Assistant / Board Liaison Tim Meinke, Senior Director of Major Gifts Geoffrey Bell, Political Manager Sean Meloy, Senior Political Director Robert Byrne, Digital Communications Manager Courtney Mott, Victory Campaign Board Director Katie Creehan, Director of Operations Aaron Samulcek, Chief Operations Officer Dan Gugliuzza, Data Manager Bryant Sanders, Corporate and Foundation Gifts Manager Emily Hammell, Events Manager Seth Schermer, Vice President of Development Elliot Imse, Senior Director of Communications Cesar Toledo, Political Associate 1 | A Rainbow Wave: 2018 Annual Report Friend, As the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall Uprising approaches this June, I am reminded that every so often—perhaps just two or three times a decade—our movement takes an extraordinary leap forward in its march toward equality. -

2020 ASAC COLORADO Elections Report

Colorado Election 2020 Results This year, Colorado turned even more blue. President Donald Trump lost to Joe Biden by double-digit margins. Senator Cory Gardner lost to former Governor John Hickenlooper, making all statewide elected officials Democrats for the first time in 84 years. In the only competitive congressional race (3rd), newcomer Lauren Boebert (R) beat former state representative Diane Mitsch Bush (D). In the State House: • Representative Bri Buentello (HD 47) lost her seat to Republican Stephanie Luck • Representative Richard Champion (HD 38) lost his seat to Democrat David Ortiz • Republicans were trying to cut the Democrat majority by 3 seats to narrow the committee make up but ¾ targeted Democrats Reps. Cutter, Sullivan, and Titone held their seats • Democrats will control the House with the same 41-24 margin House Democratic Leadership • Speaker – Rep. Alec Garnett (Denver) unopposed (Rep. Becker term limited) • Majority Leader – Rep. Daneya Esgar (Pueblo) • Assistant Majority Leader – Rep. Serena Gonzales-Gutierrez (Denver • Co-caucus chairs – Rep. Meg Froelich (Denver) and Rep. Lisa Cutter (Jefferson County) • Co-whips – Rep. Kyle Mullica (Northglenn) and Rep. Monica Duran (Wheat Ridge) • The Speaker Pro Tempore will be appointed later. Current Speaker Pro Tem Janet Bucker was elected to the Senate. • Democratic JBC members are appointed in the House and Rep. Esgar’s slot will need to be filled. Rep. McCluskie is the other current Democratic member. House Republican Leadership • Minority Leader – Hugh McKean (Loveland) -

Elections Report PROTECTING COLORADO’S ENVIRONMENT

2018 Elections Report PROTECTING COLORADO’S ENVIRONMENT 2018 ELECTIONS REPORT Conservation Colorado 1 A MESSAGE FROM THE Executive Director A PRO-CONSERVATION GOVERNOR For Colorado Dear friend of Polis ran — and won — on a pro-conservation Colorado, vision for Colorado’s future: addressing climate We did it! Conservation change, growing our clean energy economy, Colorado invested and protecting our public lands. more money, time, and effort in this year’s elections than we ever have before, and it paid off. With your support, we helped pro-conservation candidates win their races for governor, attorney general, and majorities in the state House and Senate, meaning we are set up to pass bold policies to protect our air, land, water, and communities. This year’s election marks progress for many reasons. More than 100 women were elected to the U.S. House for the first time in history, including the OUR STAFF WITH JARED POLIS IN GRAND JUNCTION POLIS ADDRESSING VOLUNTEER CANVASSERS first-ever Native American and Muslim women. To help elect Jared Polis, and Senate. We need these pro- Governor-elect Polis and We made some history here in Conservation Colorado and conservation leaders to act with countless state legislators ran Colorado, too. Joe Neguse will be its affiliated Political Action urgency to address the greatest on a commitment to clean our state’s first African American Committees (PACs) spent more threat we’re facing: climate energy. That’s because they representative in Congress, and than $2.6 million and knocked change. know Colorado has always Jared Polis is the first openly gay more than 500,000 doors. -

Bolderboulder 10K Results

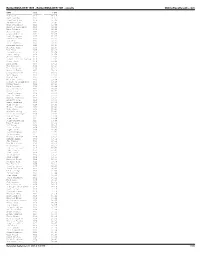

BolderBOULDER 1986 - BolderBOULDER 10K - results OnlineRaceResults.com NAME DIV TIME ---------------------- ------- ----------- Jon Luff M18 31:14 Jeff Sanchez M20 31:23 Jonathan Hume M18 31:58 Ed Ostrovich M27 32:04 Mark Stromberg M21 32:09 Michael Velasquez M16 32:21 Rick Renfrom M32 32:22 James Ysebaert M22 32:24 Louis Anderson M32 32:25 Joel Thompson M27 32:27 Kevin Collins M31 32:34 Rob Welo M22 32:42 Bill Lawrance M31 32:44 Richard Bishop M28 32:45 Chester Carl M33 32:47 Bob Fink M29 32:51 David Couture M18 32:54 Brent Terry M24 32:58 Chris Nelson M16 33:02 Robert III Hillgrove M18 33:05 Steve Smith M16 33:08 Rick Katz M37 33:11 Tom Donohoue M30 33:14 Dale Garland M28 33:17 Michael Tobin M22 33:18 Craig Marshall M28 33:20 Mark Weeks M34 33:21 Sam Wolfe M27 33:23 William Levine M25 33:26 Robert Jr Dominguez M30 33:26 David Teague M32 33:28 Alex Accetta M16 33:29 Dave Dreikosen M32 33:31 Peter Boes M22 33:32 Daniel Bieser M24 33:32 Matt Strand M18 33:33 George Frushour M23 33:34 Everett Bear M16 33:35 Bruce Pulford M31 33:36 Jeff Stein M26 33:40 Thomas Teschner M22 33:42 Mike Chase M28 33:43 Michael Junig M21 33:43 Parrick Carrigan M26 33:44 Jay Kirksey M30 33:46 Todd Moore M22 33:49 Jerry Duckworth M24 33:49 Rick Reimer M37 33:50 RaY Keogh M28 33:50 Dave Dooley M39 33:50 Roger Innes M26 33:50 David Chipman M22 33:51 Brian Boehm M17 33:51 Michael Dunlap M29 33:51 Arthur Mizzi M30 33:52 Jim Tanner M18 33:52 Bob Hillgrove M41 33:52 Ramon Duran M18 33:52 Ken Jr. -

Employee Or Independent Contractor? Classification Yb the Internal Revenue Service

North East Journal of Legal Studies Volume 12 Fall 2006 Article 1 Fall 2006 Employee or Independent Contractor? Classification yb The Internal Revenue Service Martin H. Zern Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fairfield.edu/nealsb Recommended Citation Zern, Martin H. (2006) "Employee or Independent Contractor? Classification yb The Internal Revenue Service," North East Journal of Legal Studies: Vol. 12 , Article 1. Available at: https://digitalcommons.fairfield.edu/nealsb/vol12/iss1/1 This item has been accepted for inclusion in DigitalCommons@Fairfield by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Fairfield. It is brought to you by DigitalCommons@Fairfield with permission from the rights- holder(s) and is protected by copyright and/or related rights. You are free to use this item in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses, you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 I Vol. 16 I North East Journal of Legal Studies OTHER ARTICLES EMPLOYEE OR INDEPENDENT CONTRACTOR? THE TRANSFER OF NONQUALIFIED DEFERRED CLASSIFICATION BY THE INTERNAL REVENUE COMPENSATION AND NONSTATUTORY STOCK SERVICE OPTIONS: THE INTERACTION OF THE ASSIGNMENT OF INCOME DOCTRINE AND by INTERNAL REVENUE CODE § 1041? Vincent R. Barrel/a.............................. 122 Martin H. Zem* USING GOOD STORIES TO TEACH THE LEGAL ENVIRONMENT I. BACKGROUND Arthur M Magaldi and SaulS. Le Vine..... 134 A frequent and contentious issue existing between businesses and the Internal Revenue Service ("IRS") is the proper classification of persons hired to perform services. -

Construction Industry

CONSTRUCTION INDUSTRY Under California law, a contractor, licensed or unlicensed, In addition to the above factors, the individual must have who engages the services of unlicensed subcontractors a valid contractor’s license to perform the work. or construction workers is, by specific statute, the employer of those unlicensed subcontractors or workers, The bottom line is that without a valid contractor’s license even if the subcontractors or workers are independent a person performing services in the construction trade is contractors under the usual common law rules. an employee of the contractor who either holds a license or is required to be licensed. A contractor is any person who constructs, alters, repairs, adds to, subtracts from, improves, moves, The term “valid license” means the license was issued to wrecks or demolishes any building, highway, road, the correct individual or entity, the license was for the parking facility, railroad, excavation or other structure, type of service being provided, and the license was for project, development or improvement, or does any part the entire period of the job. thereof, including the erection of scaffolding or other structures or works or the cleaning of grounds or struc- The Contractor’s State License Board (CSLB) deter- tures in connection therewith. The term contractor mines who must be licensed to perform services in the includes subcontractor and specialty contractor. construction industry within California. A contractor or a worker should contact the CSLB to determine if the Who is a Statutory Employee in the Construction services performed require a license. You should docu- Industry? ment the CSLB determination. -

General Assembly State of Colorado Denver

General Assembly State of Colorado Denver August 14, 2020 Colorado Oil & Gas Conservation Commission 1120 Lincoln St #801 Denver, CO 80203 Via email: [email protected] Nearly a decade in the making, the Colorado legislature passed Senate Bill 19-181 last year, charging the Colorado Oil and Gas Conservation Commission (COGCC) “shall regulate oil and gas operations in a manner to protect and minimize adverse impacts to public health, safety, and welfare, the environment, and wildlife resources and shall protect against adverse impacts on any air, water, soil, or biological resources resulting from oil and gas operations.” This historic bill shifted our state focus to better prioritize health and safety as we also regulate this important industry. SB19-181 also made a significant change to the agency itself shifting the COGCC to full time members who can focus on these key issues. In the coming months, we know that your hard work will be key to implementing the legislative vision of this law. Your presence on this commission is intended to ensure fulfillment of the agency’s new mission. Truly, our constituents and local economies are relying on you, in this role, to help improve their overall wellbeing. This is no small task, which is why your expertise and willingness to join this effort makes us proud. We appreciate your support improving protections for public health, safety, and the environment. Due to the previous mission, COGCC commissioners and staff were often drawn between competing interests, often in conflict. This led to permits granted for oil and gas facilities that were not protective of public health, safety, welfare, the environment and wildlife. -

PPP Guidance for Self Employed Individuals and Partnerships

PPP Guidance for Self- Employed and Partnerships Presented by Stacy Shaw, CPA, MBA & Chris Wittich, CPA, MBT April 15, 2020 1 Agenda •General Overview •EIDL vs PPP loan •PPP Loan Details •PPP Loan Forgiveness •Q & A 2 • SBA Economic Injury Disaster Loan (EIDL) • EIDL Emergency ADvance General • Paycheck Protection Program Loan (PPP) Overview • Existing SBA Loans • Information OverloaD • Fear BaseD Decisions 3 3 EIDL PPP ECONOMIC INJURY DISASTER LOAN PAYROLL PROTECTION PROGRAM • Existing SBA LenDers – plus new lenders are • Directly through the SBA coming online this week • $2 million max, up to $10K advance • 2.5 x average payroll costs, $10M max • Up to 30 years, 3.75% or 2.75% • 2 years, 1% interest rate • Expenses not covered due to COVID19 • Payroll, interest on mortgage anD other loans, • Guarantee > $200K, Collateral over $25K rent anD utilities • No forgiveness except on advance • No guarantee or collateral • Funding has been very slow on both the • Yes on forgiveness, as DefineD EIDL and the $10k advance, lots of these • Now accepting applications for businesses anD are being rejecteD self-employed 4 Details of PPP Loans • If you receiveD EIDL loan between 1-31-20 anD 4-3-20, you may apply for PPP, if EIDL was useD for payroll costs you must use PPP loan to refinance EIDL – you can Do EIDL anD PPP but must be for Different purposes • Loans are required to be funDed by 6-30-20, forgivable anD allowable uses can go past 6-30-20 • LenDer must make 1st disbursement of loan no later than 10 days from loan approval. -

S/L Sign on Letter Re: Rescue Plan State/Local

February 17, 2021 U.S. House of Representatives Washington, D.C. 20515 U.S. Senate Washington, D.C. 20510 Dear Members of Congress: As elected leaders representing communities across our nation, we are writing to urge you to take immediate action on comprehensive coronavirus relief legislation, including desperately needed funding for states, counties, cities, and schools, and an increase in states’ federal medical assistance percentage (FMAP). President Biden’s ambitious $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan will go a long way towards alleviating the significant financial strain COVID-19 has placed on our states, counties, cities, and schools, and the pocketbooks of working families. Working people have been on the frontlines of this pandemic for nearly a year and have continued to do their jobs during this difficult time. Dedicated public servants are still leaving their homes to ensure Americans continue to receive the essential services they rely upon: teachers and education workers are doing their best to provide quality education and keep their students safe, janitors are still keeping parks and public buildings clean, while healthcare providers are continuing to care for the sick. Meanwhile, it has been ten months since Congress passed the CARES Act Coronavirus Relief Fund to support these frontline workers and the essential services they provide. Without significant economic assistance from the federal government, many of these currently-middle class working families are at risk of falling into poverty through no fault of their own. It is a painful irony that while many have rightly called these essential workers heroes, our country has failed to truly respect them with a promise to protect them and pay them throughout the crisis.