1. Letter to Krishnadas1 2. Letter to Balkrishna Bhave

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

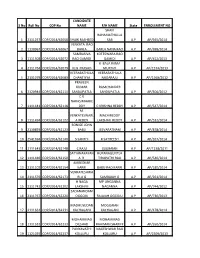

MEL Unclaimed Dividend Details 2010-2011 28.07.2011

MUKAND ENGINEERS LIMITED FINAL FOLIO DIV. AMT. NAME FATHERS NAME ADDRESS PIN CODE IEFP Trns. Date IN30102220572093 48.00 A BHASKER REDDY A ASWATHA REDDY H NO 1 1031 PARADESI REDDY STREET NR MARUTHI THIYOTOR PULIVENDULA CUDDAPAH 516390 03-Aug-2017 A000006 60.00 A GAFOOR M YUSUF BHAIJI M YUSUF 374 BAZAR STREET URAN 400702 03-Aug-2017 A001633 22.50 A JANAKIRAMAN G ANANTHARAMA KRISHNAN 111 H-2 BLOCK KIWAI NAGAR KANPUR 208011 03-Aug-2017 A002825 7.50 A K PATTANAIK A C PATTANAIK B-1/11 NABARD NAGAR THAKUR COMPLEX KANDIVLI E BOMBAY 400101 03-Aug-2017 A000012 12.00 A KALYANARAMAN M AGHORAM 91/2 L I G FLATS I AVENUE ASHOK NAGAR MADRAS 600083 03-Aug-2017 A002573 79.50 A KARIM AHMED PATEL AHMED PATEL 21 3RD FLR 30 NAKODA ST BOMBAY 400003 03-Aug-2017 A000021 7.50 A P SATHAYE P V SATHAYE 113/10A PRABHAT RD PUNE 411004 03-Aug-2017 A000026 12.00 A R MUKUNDA A G RANGAPPA C/O A G RANGAPPA CHICKJAJUR CHITRADURGA DIST 577523 03-Aug-2017 1201090001143767 150.00 A.R.RAJAN . A.S.RAMAMOORTHY 4/116 SUNDAR NAGARURAPULI(PO) PARAMAKUDI. RAMANATHAPURAM DIST. PARAMAKUDI. 623707 03-Aug-2017 A002638 22.50 ABBAS A PALITHANAWALA ASGER PALITHANAWALA 191 ABDUL REHMAN ST FATEHI HOUSE 5TH FLR BOMBAY 400003 03-Aug-2017 A000054 22.50 ABBASBHAI ADAMALI BHARMAL ADAMLI VALIJI NR GUMANSINHJI BLDG KRISHNAPARA RAJKOT GUJARAT 360001 03-Aug-2017 A000055 7.50 ABBASBHAI T VOHRA TAIYABBHAI VOHRA LOKHAND BAZAR PATAN NORTH GUJARAT 384265 03-Aug-2017 A006583 4.50 ABDUL AZIZ ABDUL KARIM ABDUL KARIM ECONOMIC INVESTMENTS R K SHOPPING CENTRE SHOP NO 6 S V ROAD SANTACRUZ W BOMBAY 400054 03-Aug-2017 A002095 60.00 ABDUL GAFOOR BHAIJI YUSUF 374 BAZAR ROAD URAN DIST RAIGAD 400702 03-Aug-2017 A000057 15.00 ABDUL HALIM QUERESHI ABDUL KARIM QUERESHI SHOP NO 1 & 2 NEW BBY SHOPPPING CET JUHU VILE PARLE DEVLOPEMENT SCHEME V M RD VILE PARLE WEST BOMBAY 400049 03-Aug-2017 IN30181110055648 15.00 ABDUL KAREEM K. -

Songs by Title Karaoke Night with the Patman

Songs By Title Karaoke Night with the Patman Title Versions Title Versions 10 Years 3 Libras Wasteland SC Perfect Circle SI 10,000 Maniacs 3 Of Hearts Because The Night SC Love Is Enough SC Candy Everybody Wants DK 30 Seconds To Mars More Than This SC Kill SC These Are The Days SC 311 Trouble Me SC All Mixed Up SC 100 Proof Aged In Soul Don't Tread On Me SC Somebody's Been Sleeping SC Down SC 10CC Love Song SC I'm Not In Love DK You Wouldn't Believe SC Things We Do For Love SC 38 Special 112 Back Where You Belong SI Come See Me SC Caught Up In You SC Dance With Me SC Hold On Loosely AH It's Over Now SC If I'd Been The One SC Only You SC Rockin' Onto The Night SC Peaches And Cream SC Second Chance SC U Already Know SC Teacher, Teacher SC 12 Gauge Wild Eyed Southern Boys SC Dunkie Butt SC 3LW 1910 Fruitgum Co. No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) SC 1, 2, 3 Redlight SC 3T Simon Says DK Anything SC 1975 Tease Me SC The Sound SI 4 Non Blondes 2 Live Crew What's Up DK Doo Wah Diddy SC 4 P.M. Me So Horny SC Lay Down Your Love SC We Want Some Pussy SC Sukiyaki DK 2 Pac 4 Runner California Love (Original Version) SC Ripples SC Changes SC That Was Him SC Thugz Mansion SC 42nd Street 20 Fingers 42nd Street Song SC Short Dick Man SC We're In The Money SC 3 Doors Down 5 Seconds Of Summer Away From The Sun SC Amnesia SI Be Like That SC She Looks So Perfect SI Behind Those Eyes SC 5 Stairsteps Duck & Run SC Ooh Child SC Here By Me CB 50 Cent Here Without You CB Disco Inferno SC Kryptonite SC If I Can't SC Let Me Go SC In Da Club HT Live For Today SC P.I.M.P. -

Volume Fourty-One : (Dec 2, 1927

1. SPEECH AT PUBLIC MEETING, CHICACOLE December 3, 1927 You seem to be dividing all the good things with poor Utkal1. I flattered myself with the assumption that my arrival here is one of the good things, for I was going to devote all the twenty days to seeing the skeletons of Orissa; but as you, the Andhras, are the gatekeepers of Orissa on this side, you have intercepted my march. But I am glad you have anticipated me also. After entering Andhra Desh, I have been doing my business with you and I know God will reward all those unknown people who have been co-operating with me who am a self- appointed representative of Daridranarayana. And here, too, you have been doing the same thing. Last night, several sister came and presented me with a purse. But let me tell you this is not after all my tour in Andhra. I am not going to let you alone so easily as this, nor will Deshabhakta Konda Venkatappayya let me alone, because I have toured in some parts of Ganjam. I am under promise to tour Andhra during the early part of next year, and let me hope what you are doing is only a foretaste of what you are going to do next year. You have faith in true non-co-operation. There is the great drink evil, eating into the vitals of the labouring population. I would like you to non-co-operate with that evil without a single thought and I make a sporting proposal, viz., that those who give up drink habit should divide their savings with me on behalf of Daridranarayan. -

S No Roll No COP No CANDIDATE NAME F/H NAME State

CANDIDATE S No Roll No COP No NAME F/H NAME State ENROLLMENT NO SHAIK RAHAMATHULLA 1 2111257 COP/2014/62058 SHAIK RASHEED SAB A.P AP/945/2014 VENKATA RAO 2 1130967 COP/2014/62067 BARLA BARLA NANA RAO A.P AP/698/2014 SAMBASIVA KOTESWARA RAO 3 1111308 COP/2014/62072 RAO GAMIDI GAMIDI A.P AP/452/2013 K BALA RAMA 4 2111764 COP/2014/62079 KLN PRASAD MURTHY A.P AP/1574/2013 VEERABATHULA VEERABATHULA 5 2131079 COP/2014/62083 CHANTIYYA NAGARAJU A.P AP/1568/2012 PRAVEEN KUMAR RAMCHANDER 6 2120944 COP/2014/62111 SANDUPATLA SANDUPATLA A.P AP/306/2012 C V NARASIMHARE 7 1111441 COP/2014/62118 DDY C KRISHNA REDDY A.P AP/547/2014 M. VENKATESWARL MACHIREDDY 8 1111494 COP/2014/62122 A REDDY LAKSHMI REDDY A.P AP/532/2014 BONIGE JOHN 9 2130893 COP/2014/62123 BABU JEEVARATNAM A.P AP/878/2014 10 2541694 COP/2014/62140 S SANTHI R SATHEESH A.P AP/267/2014 11 2111643 COP/2014/62148 C RAJU SUGRAIAH A.P AP/1238/2011 SATYANARAYAN RUPANAGUNTLA 12 1111480 COP/2014/62150 A R. TIRUPATHI RAO A.P AP/540/2014 AMBEDKAR 13 2131102 COP/2014/62154 KARRI BABU RAO KARRI A.P AP/180/2014 VENKATESHWA 14 2111570 COP/2014/62173 RLU G SAMBAIAH G A.P AP/261/2014 H NAGA MP LINGANNA 15 2111742 COP/2014/62202 LAKSHMI NAGANNA A.P AP/744/2012 SADANANDAM 16 2111767 COP/2014/62220 OGGOJU RAJAIAH OGGOJU A.P AP/736/2013 MADHUSUDAN MOGILAIAH 17 2111661 COP/2014/62231 KACHAGANI KACHAGANI A.P AP/478/2014 MOHAMMAD MOHAMMAD 18 1111532 COP/2014/62233 DILSHAD RAHIMAN SHARIFF A.P AP/550/2014 PUNYAVATHI NAGESHWAR RAO 19 1121035 COP/2014/62237 KOLLURU KOLLURU A.P AP/2309/2013 G SATHAKOTI GEESALA 20 2131021 COP/2014/62257 SRINIVAS NAGABHUSHANAM A.P AP/1734/2011 GANTLA GANTLA SADHU 21 1131067 COP/2014/62258 SANYASI RAO RAO A.P AP/1802/2013 KOLICHALAM NAVEEN KOLICHALAM 22 1111688 COP/2014/62265 KUMAR BRAHMAIAH A.P AP/1908/2010 SRINIVASA RAO SANKARA RAO 23 2131012 COP/2014/62269 KOKKILIGADDA KOKKILIGADDA A.P AP/793/2013 24 2120971 COP/2014/62275 MADHU PILLI MAISAIAH PILLI A.P AP/108/2012 SWARUPARANI 25 2131014 COP/2014/62295 GANJI GANJIABRAHAM A.P AP/137/2014 26 2111507 COP/2014/62298 M RAVI KUMAR M LAXMAIAH A.P AP/177/2012 K. -

Volume Ninety-Four : (Feb 17, 1947

1. A LETTER DEVIPUR , February 17, 1947 My reply to your previous letter was still pending when I got this second one from you. But there was nothing in your first letter that needed immediate reply. At present there is great strain on me, both physical and mental. My work here instead of getting easier is becoming more difficult each day, as oppsition is increasing. All the same, my faith and courage are steadily growing. After all, I am here to do or die, am I not? There is no middle course here. .1 It is not certain when the third stage of my tour will begin. I have to reach Haimchar on the 24th. .2 The further programme will depend on how exhausted I feel. I shall be satisfied if God sustains me through the programme even up to the 24th. [From Gujarati] Eklo Jane Re, p. 144 2. ADVICE TO A CONGRESS WORKER3 DEVIPUR , February 17, 1947 Did you realize that by indulging in this vain display you would acerbate communal passions? This display means nothing to me. .4 but it will leave a legacy of ill-will behind which will continue to poison the communal relations in this village for a long time to come. You are a Congressman. Did not it occur to you, knowing my strong views on khadi, that ribbons and buntings made of mill cloth would only hurt me? I wouldn’t have felt so hurt if, instead of floral decorations, you had presented me with garlands of yarn. They are decorative, and 1 Omissions as in the source 2 Ibid 3 A grand reception had been arranged for Gandhiji at Devipur. -

![1. LETTER to PARASRAM MEHROTRA [Before June 16, 1932]1 CHI](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8149/1-letter-to-parasram-mehrotra-before-june-16-1932-1-chi-738149.webp)

1. LETTER to PARASRAM MEHROTRA [Before June 16, 1932]1 CHI

1. LETTER TO PARASRAM MEHROTRA [Before June 16, 1932]1 CHI. PARASRAM, Judging from your letter the children seem to have made good progress. You speed with the takli is also good. Do give half an hour daily to it; if you can in what time spin 160 rounds, nothing can be better than that. What does kule ki haddi2 mean? The word Kula is not to be found in the Hindi Dictionary. Why did the haddi get swollen? Has the swelling subsided now? If it has not, you must take immediate steps to cure it. The replies to the questions which you have put to Mahadev are: 1. I consider a minimum of half an hour’s walk morning and evening essential for you and others. It is not necessary to sit in one position for more than an hour. One should stand up for a minute at least, or change the posture. 2. It is natural that a mother should desire to see her son, but every mother ought to restrain such a with and, if the son is engaged in some activity of service, he must cure his mother of such attachment. 3. When a son goes abroad and lives in a foreign country for ten years, his mother has no choice but to bear the separation. There are innumerable poor mothers in India who possibly never again see the face of their son after he has gone out to earn a living. One may console the mother through a letter, and cheer her as much as one can by reasoning with her and citing other similar instances. -

Why I Became a Hindu

Why I became a Hindu Parama Karuna Devi published by Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Copyright © 2018 Parama Karuna Devi All rights reserved Title ID: 8916295 ISBN-13: 978-1724611147 ISBN-10: 1724611143 published by: Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Website: www.jagannathavallabha.com Anyone wishing to submit questions, observations, objections or further information, useful in improving the contents of this book, is welcome to contact the author: E-mail: [email protected] phone: +91 (India) 94373 00906 Please note: direct contact data such as email and phone numbers may change due to events of force majeure, so please keep an eye on the updated information on the website. Table of contents Preface 7 My work 9 My experience 12 Why Hinduism is better 18 Fundamental teachings of Hinduism 21 A definition of Hinduism 29 The problem of castes 31 The importance of Bhakti 34 The need for a Guru 39 Can someone become a Hindu? 43 Historical examples 45 Hinduism in the world 52 Conversions in modern times 56 Individuals who embraced Hindu beliefs 61 Hindu revival 68 Dayananda Saraswati and Arya Samaj 73 Shraddhananda Swami 75 Sarla Bedi 75 Pandurang Shastri Athavale 75 Chattampi Swamikal 76 Narayana Guru 77 Navajyothi Sree Karunakara Guru 78 Swami Bhoomananda Tirtha 79 Ramakrishna Paramahamsa 79 Sarada Devi 80 Golap Ma 81 Rama Tirtha Swami 81 Niranjanananda Swami 81 Vireshwarananda Swami 82 Rudrananda Swami 82 Swahananda Swami 82 Narayanananda Swami 83 Vivekananda Swami and Ramakrishna Math 83 Sister Nivedita -

THE WELTE Philharmonic Organ Vorsetzer

IHTERHATlOHAL CHAPTER OFFICERS OFFICERS NO. CALIFORNIA Pres.: Phil McCoy PRESIDENT Vice Pres.: Isadora Kolt Bob Rosencrans Treas.: Bob Wilcox 36 Hampden Rd. Sec.lReporter: Jack & Upper Darby, PA 19082 Dianne Edwards VICE PRESIDENT SO. CALIFORNIA Bill Eicher Pres.: Francis Cherney 465 Winding Way Vice Pres.: Mary Lilien Day1on, OH 45429 Sec.: Evelyn Meerler SECRETARY Treas: Roy Shelso Jim Weisenborne Reporter: Bill Toeppe 73 Nevada St TEXAS Rochester, MI 48063 Pres. Jim Phillips PUBLISHER Vice Pres: Merrill Baltzley AMICA MEMBERSHIP RATES: Tom Beckett Sec/Treas.: Janet Tonnesen Reporter James Kelsey Continuing Members: $15 Dues 6817 Cliltbrook Dallas, TX 75240 MIDWEST New Members, add $5 processing fee MEMBERSHIP SECRETARY Pres.: Bennet Leedy Lapsed Members, add $3 processing fee (New memberships and Vice Pres.: Jim Prendergast mailing problems) Sec.: Jim Weisenborne Bobby Clark Jr Treas.: Alvin Wulfekuhl P O. Box 172 Reporter: Molly Yeckley Columbia SC 29202 PHILADELPHIA AREA TREASURER Pres.: Len Wert THE AMICA NEWS BULLETIN Jack & Mary Riffle Vice Pres.: Harvard Wood 5050 Eastside Calpella Rd. Sec.: Beverly Naddeo Published by the Automatic Musicsllnstrument Collectors' Association, a non Ukiah, CA 95482 Treas.: Doris Berry profrt club devoted to the restoration, distribution and enloyment of musical Reporter: Dick Price instruments using perforated paper music rolls. BOARD REPRESENTATIVES N. Cal: Howie Koff SOWNY (So. Ontario, West NY) Contributions: All subjects of interest to readers of the Bulletin are S Cal Dick Rigg Pres: Bruce Bartholomew encouraged and invited by the publisher. All articles must be received by the Texas: Wade Newton Vice Pres: Mike Walter 10th of the preceeding month Every attempt will be made to publish all articles Phil: Bob Taylor Sec. -

Select Index

SELECT INDEX Abdul Gafoor, 1023 Amboskar, Dr. Shantaram Abdul Hamid, 115 Ramchandra, 630 Abdul Karim, 1023 Ambulkar, Pandharinath, 938 Abdul Majid, 410, 533, 563 Amin, Shankarlal, 25 Amrutkar, N. G., 967 Abdul Rahman Sulaiman Cassum Ane, M. S., 389, 921, 938 Mitha, 533, 554, 558 Ane, Dr. Y. S., 998, 1009 Abdul Rashid, 547 Ansari, Dr., 1022 Abdul Rauf, 639 Antone, Philip, 71, 191 Abdul Razzak, 933, 974 Antrolikar, Dr. K. B., 601, 645, Abdul Rehman, 484 768 Abdul Sakur, 492 Apte, Moreshwar Ganesh, 948 Abdul Wahab, 922 Apte, Pandurang Shridhar, 624 Apte, S. A., 487 Abdulla Rahimtulla, 636, 649, 703, 837 Apte, Vishnu Ganesh, 592, 718 Abhyankar, C. V., 693 Ardeshir, Dadabhai, 801 Abhyankar, J. P., 577 Ardeshwar, Vithalrao, 954 Abhyankar, M. V., 900, 911, 927 Atavnekar, W. V., 803 Abhyankar, Waman Vishnu, 791 Athavle, Dr. Vasudev Vinayak, Abidali Jafferbhai, 15, 16, 17, 79 583, 703 Acharekar, R. H., 222 Athawale, Balwant Mukund, 937 Acharekar, R. K., 187, 307, 546 Atikar, V. V., 731. 752 Avari, Manchershah 145 Acharya, Narayan Gajanan, 828 Azad, Abul Kalam, 355, 827 Acharya, T. L., 568 Babrekar, D. S., 546, 559 Acharya, Wasudeo P., 813, 825 Bachchu Maharaj, 949 Adhikari, Ramchandra Vishwanath, 702 Badhai, Bajirao, 1042 Agarkar, Sitaram, 948 Badhai, Sakharam, 1034 Agarwal, Sukhdeo, 1028 Bairagi, Sitaramdas Tikamdas, 577, Ahmad Saeed, 161, 184, 190 595 Bajaj, Jamnalal, 12, 56, 576, Ajinkya, N. A., 471 877 Akhtar Ali Khan, 914 Bajaj, Mrs. Janakibai, 695, 793 Akut, Vasudeo Bapuji, 578, 650 Ballal, Dr. K. H., 969 Ali Bahadurkhan, 188 Bamangaonkar, N. R., 895, 1012 Ali, J. -

Gandhi and Sexuality: in What Ways and to What Extent Was Gandhi’S Life Dominated by His Views on Sex and Sexuality? Priyanka Bose

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by The South Asianist Journal Gandhi and sexuality: in what ways and to what extent was Gandhi’s life dominated by his views on sex and sexuality? Priyanka Bose Vol. 3, No. 1, pp. 137–177 | ISSN 2050-487X | www.southasianist.ed.ac.uk www.southasianist.ed.ac.uk | ISSN 2050-487X | pg. 137 Vol. 3, No. 1, pp. 137–177 Gandhi and sexuality: in what ways and to what extent was Gandhi’s life dominated by his views on sex and sexuality? Priyanka Bose [email protected] Though research is coming to light about Gandhi’s views on sexuality, there is still a gap in how this can be related or focused to his broader political philosophy and personal conduct. Joseph Alter states: “It is well known that Gandhi felt that sexuality and desire were intimately connected to social life and politics and that self-control translated directly into power of various kinds both public and private.”* However, I would argue, that the ways in which Gandhi connected these aspects, why and how, have not been fully discussed and are, indeed, not well known. By studying his views and practices with relation to sexuality, I believe that much can be discerned as to how his political philosophy and personal conduct were both established and acted out. In this paper I will aim, therefore, to address: what his views were on sex and sexuality, contextualizing his views with those of the time, what his influences were in his ideology on sex, and how these ideologies framed and related to his political philosophy as well as conduct. -

“Writing About Music” Vol

UCLA Department of Musicology presents MUSE An Undergraduate Research Journal “Writing About Music” Vol. 1, No. 1 “Dissonant Ones: The Harmony of Lou Reed and “Waitress! Equalitea and Pie, Please” John Cale” Irena Huang Gabriel Deibel “Boy Band: Intersecting Gender, Age, Sexuality, “A Possible Resolution for the Complicated and Capitalism” Feelings Revolving Around Tyler, the Creator” Grace Li Isabel Nakoud “Being the Cowboy: Mitski’s Rewriting of Gender Roles in Indie Rock” Jenna Ure Winter 2020 2 3 UCLA Department of Musicology presents MUSE An Undergraduate Research Journal Volume 1, Number 1 Winter 2020 Contents Introduction from the Editors 4 Being the Cowboy: Mitski’s Rewriting of Gender Roles in Indie 6 Rock Editor-in-Chief Jenna Ure Matthew Gilbert Waitress! Equalitea and Pie, Please 16 Managing Editor Irena Huang Alana Chester Dissonant Ones: The Harmony of Lou Reed and John Cale 26 Review Editor Gabriel Deibel Karen Thantrakul Boy Band: Intersecting Gender, Age, Sexuality, and Capitalism 36 Technical Editors Grace Li J.W. Clark Liv Slaby A Possible Resolution for the Complicated Feelings Revolving 46 Gabriel Deibel Around Tyler, the Creator Isabel Nakoud Faculty Advisor Dr. Elisabeth Le Guin Closing notes 62 4 Introduction Introduction 5 Introduction Li’s discussion of the exploitation of boy band One Direction, Gabriel Deibel’s essay on the influence of John Cale on the Velvet Underground’s experimental sound, a feminist exploration by Irena Huang of the musical Alana Chester, Matthew Gilbert, and Karen Waitress (composed by a UCLA alumnus, Sara Bareilles), and a critique Thantrakul of the music industry through indie singer Mitski’s music by Jenna Ure. -

Sage's Mission

SAGE’S MISSION SAGE’S MISSION English Version of TWENTY ‘GULAB VATIKA’ BOOKLETS Life Mission of Saint Gulabrao Maharaj Translated By Vasant Joshi Published by Vasant Joshi SAGE’S MISSION SAGE’S MISSION English Version of TWENTY ‘GULAB VATIKA’ BOOKLETS Life Mission of Saint Gulabrao Maharaj * Self Published by: Vasant Joshi English Translator: © Vasant Joshi B-8, Sarasnagar, Siddhivinayak Society, Shukrawar Peth, Pune 411021. Mobile.: +91-9422024655 | Email : [email protected] * All rights reserved with English Translator No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the English Translator. * Typesetting and Formatting Books and Beyond Mrs Ujwala Marne New Ahire Gaon, Warje, Pune. Mobile. : +91-8805412827 / 7058084127 | Email: [email protected] * Cover Design by : Aadity Ingawale * First Edition : 21st March 2021 * Price : ₹ 500/- SAGE’S MISSION DEDICATED TO THE MEMORY OF MY WIFE LATE VRINDA JOSHI yG y SAGE’S MISSION INDEX Subject Page No. � Part I I to XVIII Prologue of English Translator by Vasant Joshi II Babaji Maharaj Pandit III Life Graph IV Life Mission VIII Literature Treasure Trove XII � Part II 1 to 1. Acquaintance (By K. M. Ghatate) 3 2. Merit Honour (By Renowned Persons) 43 3. Babajimaharaj Pandit (By V. N. Pandit) 73 4. Friendship Devotion (By Vasudeorao Mule) 95 5. Mankarnika Mother (By Milind Tripurwar) 110 6. Swami Bechirananda (By Milind Tripurwar) 126 7. Autobiography (By Self) 134 8. Saint’s Departure (By Self) 144 9.