The Blues/Funk Futurism of Roger Troutman 119

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EPMD Lil Crazy

Lil Crazy EPMD Hey young world, one two, one two Check it out y'all Uhh, shadz of lingo in the house E double's in the house with def squad On the funky fresh track with shadz of lingo Mic check one two, yo you got my nerves jumpin around And _humpin' around_ like bobby brown across town I ain't with that, so don't cramp my style Step off me, I'm hyped like I had a pound of coffee Yo how could you ask what I'm doin When I'm pursuin, gettin funky with my crew and My input brings vibes unknown like e.t. Makes me phone home to my family Cling, hello mom, I'm doin it, freakin more fame Than batman played by michael keaton I crossed over, let me name someone that's black With fame, and pockets that are fat Heyyy, erick sermon, he's one Packs a gun, that's bigger than malcolm's Out the window, I look for a punk to get stupid So I can shoot his ass like cupid E 2 bingos, down with the shadz of lingo Here to bust out the funky single Ahh shit, there goes my pager I'll see you later, because yo Every now and then, I get a little crazy One two how can I do it? I guess I'll spit the real Yo I pack much dick, with the cover made of steel hoe Yes yes, never fessed or settled for less One clown stepped, and got a hole in the fuckin chest From the a.k., somebody scream mayday Took the sucker out, cause he clowned me on a payday The funk is flowin to the maximum From the e double, while I kick the facts to them Check a chill brother with class, rough enough To run up and snatch the spine out a niggaz ass Grip the steel when caps peeled, here to chill -

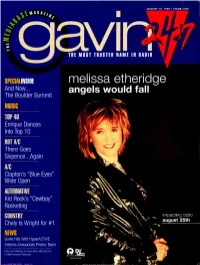

Gavin-Report-1999-08

AUGUST 16, 1999 ISSUE 2268 TOE MOST TRUSTED NAME IN RADIO tH.III'-1111; melissa etheridge And Now... angels would fall The Boulder Summit MUSIC TOP 40 Enrique Dances Into Top 10 HOT AIC There Goes Sixpence...Again AIC Clapton's "Blue Eyes" Wide Open COUNTRY impacting radio august 25th Chely Is Wright for #1 NEWS GAVIN Hits With HyperACTIVE Artemis Announces Promo Team From the Publishers of Music Week, MI and tono A Miller Freeman Publication www.americanradiohistory.com advantage Giving PDs the Programming Advantage Ratings Softwaiv designed dust for PDs! Know Your Listeners Better Than Ever with New Programming Software from Arbitron Developed with input from PDs nationwide, PD Advantage'" gives you an "up close and personal" look at listeners and competitors you won't find anywhere else. PD Advantage delivers the audience analysis tools most requested by program directors, including: What are diarykeepers writing about stations in my market? A mini -focus group of real diarykeepers right on your PC. See what listeners are saying in their diary about you and the competition! When listeners leave a station, what stations do they go to? See what stations your drive time audience listens to during midday. How are stations trending by specific age? Track how many diaries and quarter -hours your station has by specific age. How's my station trending hour by hour? Pinpoint your station's best and worst hours at home, at work, in car. More How often do my listeners tune in and how long do (c coue,r grad they stay? róathr..,2 ,.,, , Breaks down Time Spent Listening by occasions and TSL per occasion. -

Pyramid Entertainment Group

Pyramid 377 Rector Place Suite 21A New York, NY 10280 tel: 212.242.7274 fax: 212.242.6932 Entertainment Group [email protected] www.pyramid-ent.com Sal Michaels Seth Cohen Matt Santo Doug Varrichio Celebrating over three decades of providing outstanding Entertainment MORRIS DAY & THE TIME KOOL & THE GANG BB KING EXPERIENCE SISTER SLEDGE COLOR ME BADD THE JACKSONS* CLASSIC R&B FUNK HIP HOP/R&B DISCO/DANCE SPECIAL Kool & the Gang Morris Day & Keith Sweat Method Man/ Sister Sledge PACKAGES the Time Red Man KC & The Sunshine Monica Tavares POP RADIO ALL-STARS Band* Dazz Band GrandMaster Flash Nelly Gloria Gaynor FEATURING * The Jacksons Cameo Ashanti Sugarhill Gang Martha Wash Smashmouth The O’Jays Ohio Players Sean Paul MC Lyte Jody Watley Color Me Badd Maze Original Lakeside Tony! Toni! Toné! Blackstreet A Taste of Honey Deep Blue Something featuring Frankie Beverly SOS Band Slick Rick Tone Loc Thomas McClary’s Jagged Edge The Trammps Commodores Con Funk Shun Dru Hill Big Daddy Kane Thelma Houston Marcy Playground Experience Bar-Kays Ginuwine Doug E. Fresh Evelyn “Champagne” King Tag Team The Whispers Rose Royce Johnny Gill Arrested Development Stephanie Mills Zapp Bobby V DANCE ACROSS EPMD 80’s/90’s AMERICA: STUDIO ’94 Howard Hewett Midnight Star Silk CROSSOVER Ja Rule FEATURING Earth Wind and Fire Bootsy Collins Vivian Green Color Me Badd Experience Biz Markie C&C Music Factory featuring Al McKay* After 7 Tone Loc Rakim CeCe Peniston Chubby Checker Ruff Endz Vanilla Ice 112 Quad City DJs Stylistics Mystikal Tag Team Guy Real to Reel The Four Tops Twista Kid ‘n Play featuring Mad Stuntman Stokley Peabo Bryson Ying Yang Twins (voice of Mint Condition) Rob Base Crystal Waters BB King Experience Chingy J. -

112. Na Na Na 112. Only You Remix 112. Come See Me Remix 12

112. Na Na Na 112. Only You Remix 112. Come See Me Remix 12 Gauge Dunkie Butt 12 Gauge Dunkie Butt 2 Live Crew Sports Weekend 2nd II None If You Want It 2nd II None Classic 220 2Pac Changes 2Pac All Eyez On Me 2Pac All Eyez On Me 2Pac I Get Around / Keep Ya Head Up 50 Cent Candy Shop 702. Where My Girls At 7L & Esoteric The Soul Purpose A Taste Of Honey A Taste Of Honey A Tribe Called Quest Unreleased & Unleashed Above The Law Untouchable Abyssinians Best Of The Abyssinians Abyssinians Satta Adele 21. Adele 21. Admiral Bailey Punanny ADOR Let It All Hang Out African Brothers Hold Tight (colorido) Afrika Bambaataa Renegades Of Funk Afrika Bambaataa Planet Rock The Album Afrika Bambaataa Planet Rock The Album Agallah You Already Know Aggrolites Rugged Road (vinil colorido) Aggrolites Rugged Road (vinil colorido) Akon Konvicted Akrobatik The EP Akrobatik Absolute Value Al B. Sure Rescue Me Al Green Greatest Hits Al Johnson Back For More Alexander O´Neal Criticize Alicia Keys Fallin Remix Alicia Keys As I Am (vinil colorido) Alicia Keys A Woman´s Worth Alicia Myers You Get The Best From Me Aloe Blacc Good Things Aloe Blacc I Need A Dollar Alpha Blondy Cocody Rock Althea & Donna Uptown Top Ranking (vinil colorido) Alton Ellis Mad Mad Amy Winehouse Back To Black Amy Winehouse Back To Black Amy Winehouse Lioness : The Hidden Treasures Amy Winehouse Lioness : The Hidden Treasures Anita Baker Rapture Arthur Verocai Arthur Verocai Arthur Verocai Arthur Verocai Augustus Pablo King Tubby Meets Rockers Uptown Augustus Pablo In Fine Style Augustus Pablo This Is Augustus Pablo Augustus Pablo Dubbing With The Don Augustus Pablo Skanking Easy AZ Sugar Hill B.G. -

Download Download

Florian Heesch Voicing the Technological Body Some Musicological Reflections on Combinations of Voice and Technology in Popular Music ABSTRACT The article deals with interrelations of voice, body and technology in popular music from a musicological perspective. It is an attempt to outline a systematic approach to the history of music technology with regard to aesthetic aspects, taking the iden- tity of the singing subject as a main point of departure for a hermeneutic reading of popular song. Although the argumentation is based largely on musicological research, it is also inspired by the notion of presentness as developed by theologian and media scholar Walter Ong. The variety of the relationships between voice, body, and technology with regard to musical representations of identity, in particular gender and race, is systematized alongside the following cagories: (1) the “absence of the body,” that starts with the establishment of phonography; (2) “amplified presence,” as a signifier for uses of the microphone to enhance low sounds in certain manners; and (3) “hybridity,” including vocal identities that blend human body sounds and technological processing, where- by special focus is laid on uses of the vocoder and similar technologies. KEYWORDS recorded popular song, gender in music, hybrid identities, race in music, presence/ absence, disembodied voices BIOGRAPHY Dr. Florian Heesch is professor of popular music and gender studies at the University of Siegen, Germany. He holds a PhD in musicology from the University of Gothenburg, Sweden. He published several books and articles on music and Norse mythology, mu- sic and gender and on diverse aspects of heavy metal studies. -

EPMD, Chill Chill

EPMD, Chill Chill... Yeaaaa hahahaha [Erick Sermon] Equip wit the rap microchip Program aptitude one mo return oh My face in the magazines showing my eyes green (Chill...) Chill fresh new dip when I'm seen Yo dig it's the new fig for the E Double I pack a Mac 10 just in case of trouble Hot like the handle on a pot I'm steaming Fame and more glory than Morgan Freeman I'm the original my style's deformed So it can sound crazy ill when I perform Yea, check 1, 2, mic supreme EPMD, the rap American Dream Team The E-Double's definitely no joke You can't see me, even wit the microphone I'm massive dope, funky, who's deffer Yo, when I express myself like Salt 'N Pepa Erick Sermon and Parrish Smith The sickest, the wickest, crazy mad psycho, the slickest Hardcore rhymin, yea, that's the ticket Buckwhylin, ruff enuff for Long Island Chill.... Yeaaaaaa, Hahahaha.... Ruff enuff to rock New York to Long Island [PMD] Back up, boy, move easy wit the hand motion Don't even blink, kid, or I'ma start smoking The glock hammer's cocked wit the speed jock 12 shots, the bust target is the brown fox So call me smooth talk rhyme, jaywalk wit the slang talk B-boy fanatic, straight from New York The foundation, landmark of the rap scene EPMD in effect, I'm clocking mad green Like Kermit the Frog, sloppy like Boss Hog Girls runnin wild, ?paid tho' like a klondar? For mics are ready to flow in slow mo' Know the rap game just like Bo knows hoes (Yeaaaa, hahahaha)Hard, you get scarred, messing wit the Hit Squad Slide easy or catch a bullshucks charge No time to ill, stay mental or puff a pill Get the macadamians, and, oh, yea, kid, chill Chill... -

Libraryonwheels Sparksinterest

EMI Records Aligns with Erick Sermon and Def Squad Label EMI Records (EMI have always wanted for Def /Chrysalis /SBK) today Squad Records. announced a label agreement with 1 look forward to working Def Squad Records, led with Davitt by rap recording artist/producer Sigerson and the Erick whole EMI team and to having Sermon. Under this a arrangement. Sermon will very successful'relationship submit artists together." exclusively to Sermon first made his mark EMI who concentrate on devel¬ in and the rap community as half of oping producing new the classic EPMD combo. Teachers from the Bethlehem Hills ~~HFhas since Released two Happy Child Care Center brouse through the Smart Start Bookmobile. label and will continue produc¬ solo Teachers selected books for students in their class. Keith albums. No Pressure and ing Redman, Murray and Double or other established artists. Nothin' on Def Jam Def In addition to and Squad will have offices and a finding pro¬ y ducing new talent, staff based out of the EMI including On Wheels New Das EFX, Redman and Keith Library Interest York Headquarters. * By MAURICE CROCKER Sparks Murray, Sermon has also chosen for the bookmobile are Commented Davitt pro¬ Community News Reporter The first stop of the book¬ Siger- duced singles for a diverse selected by the library heads at mobile was the son, president and CEO, EMI of each Bethlehem "Erick array artists such as Super- The branch. Happy Hills Child Care Center. Records, is always cat, Blackstreet, Forsyth County Some of the books are focused or His record Shaquille Library has started a new cho¬ "I think this is a good quality. -

The Uk's Top 200 Most Requested Songs in 1980'S

The Uk’s top 200 most requested songs in 1980’s 1. Billie Jean - Michael Jackson 2. Into the Groove - Madonna 3. Super Freak Part I - Rick James 4. Beat It - Michael Jackson 5. Funkytown - Lipps Inc. 6. Sweet Dreams (Are Made of This) - Eurythmics 7. Don't You Want Me? - Human League 8. Tainted Love - Soft Cell 9. Like a Virgin - Madonna 10. Blue Monday - New Order 11. When Doves Cry - Prince 12. What I Like About You - The Romantics 13. Push It - Salt N Pepa 14. Celebration - Kool and The Gang 15. Flashdance...What a Feeling - Irene Cara 16. It's Raining Men - The Weather Girls 17. Holiday - Madonna 18. Thriller - Michael Jackson 19. Bad - Michael Jackson 20. 1999 - Prince 21. The Way You Make Me Feel - Michael Jackson 22. I'm So Excited - The Pointer Sisters 23. Electric Slide - Marcia Griffiths 24. Mony Mony - Billy Idol 25. I'm Coming Out - Diana Ross 26. Girls Just Wanna Have Fun - Cyndi Lauper 27. Take Your Time (Do It Right) - The S.O.S. Band 28. Let the Music Play - Shannon 29. Pump Up the Jam - Technotronic feat. Felly 30. Planet Rock - Afrika Bambaataa and The Soul Sonic Force 31. Jump (For My Love) - The Pointer Sisters 32. Fame (I Want To Live Forever) - Irene Cara 33. Let's Groove - Earth, Wind, and Fire 34. It Takes Two (To Make a Thing Go Right) - Rob Base and DJ EZ Rock 35. Pump Up the Volume - M/A/R/R/S 36. I Wanna Dance With Somebody (Who Loves Me) - Whitney Houston 37. -

Traditional Funk: an Ethnographic, Historical, and Practical Study of Funk Music in Dayton, Ohio

University of Dayton eCommons Honors Theses University Honors Program 4-26-2020 Traditional Funk: An Ethnographic, Historical, and Practical Study of Funk Music in Dayton, Ohio Caleb G. Vanden Eynden University of Dayton Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.udayton.edu/uhp_theses eCommons Citation Vanden Eynden, Caleb G., "Traditional Funk: An Ethnographic, Historical, and Practical Study of Funk Music in Dayton, Ohio" (2020). Honors Theses. 289. https://ecommons.udayton.edu/uhp_theses/289 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the University Honors Program at eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Traditional Funk: An Ethnographic, Historical, and Practical Study of Funk Music in Dayton, Ohio Honors Thesis Caleb G. Vanden Eynden Department: Music Advisor: Samuel N. Dorf, Ph.D. April 2020 Traditional Funk: An Ethnographic, Historical, and Practical Study of Funk Music in Dayton, Ohio Honors Thesis Caleb G. Vanden Eynden Department: Music Advisor: Samuel N. Dorf, Ph.D. April 2020 Abstract Recognized nationally as the funk capital of the world, Dayton, Ohio takes credit for birthing important funk groups (i.e. Ohio Players, Zapp, Heatwave, and Lakeside) during the 1970s and 80s. Through a combination of ethnographic and archival research, this paper offers a pedagogical approach to Dayton funk, rooted in the styles and works of the city’s funk legacy. Drawing from fieldwork with Dayton funk musicians completed over the summer of 2019 and pedagogical theories of including black music in the school curriculum, this paper presents a pedagogical model for funk instruction that introduces the ingredients of funk (instrumentation, form, groove, and vocals) in order to enable secondary school music programs to create their own funk rooted in local history. -

Funk Is Its Own Reward": an Analysis of Selected Lyrics In

ABSTRACT AFRICAN-AMERICAN STUDIES LACY, TRAVIS K. B.A. CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY DOMINGUEZ HILLS, 2000 "FUNK IS ITS OWN REWARD": AN ANALYSIS OF SELECTED LYRICS IN POPULAR FUNK MUSIC OF THE 1970s Advisor: Professor Daniel 0. Black Thesis dated July 2008 This research examined popular funk music as the social and political voice of African Americans during the era of the seventies. The objective of this research was to reveal the messages found in the lyrics as they commented on the climate of the times for African Americans of that era. A content analysis method was used to study the lyrics of popular funk music. This method allowed the researcher to scrutinize the lyrics in the context of their creation. When theories on the black vernacular and its historical roles found in African-American literature and music respectively were used in tandem with content analysis, it brought to light the voice of popular funk music of the seventies. This research will be useful in terms of using popular funk music as a tool to research the history of African Americans from the seventies to the present. The research herein concludes that popular funk music lyrics espoused the sentiments of the African-American community as it utilized a culturally familiar vernacular and prose to express the evolving sociopolitical themes amid the changing conditions of the seventies era. "FUNK IS ITS OWN REWARD": AN ANALYSIS OF SELECTED LYRICS IN POPULAR FUNK MUSIC OF THE 1970s A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF CLARK ATLANTA UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THEDEGREEOFMASTEROFARTS BY TRAVIS K. -

Soul/ Rap/ Funk/ R & B/ Disco

SOUL/ RAP/ FUNK/ R & B/ DISCO Beautiful- Christina Aguilera Night Fever- The Bee Gees Poison- Bel Biv DeVoe If I Could- Regina Belle Crazy In Love- Beyonce I Gotta Feeling- Black Eyed Peas No Diggity- Blackstreet Get Up (I Feel Like Being A) Sex Machine- James Brown I Will Survive- Cake/ Gloria Gaynor Word Up- Cameo Strokin’- Clarence Carter I Got A Woman- Ray Charles What I’d Say- Ray Charles I Like To Move, Move It- Sacha Baron Cohen Brickhouse- The Commodores Nightshift- The Commodores Hooch- Everything Dancing In The Street- Martha & The Vandellas How Sweet It Is (To Be Loved By You)- Marvin Gaye Let’s Get It On- Marvin Gaye Mercy Mercy Me (The Ecology)-Marvin Gaye Sexual Healing- Marvin Gaye What’s Going On- Marvin Gaye Crazy- Gnarls Barkley Let’s Stay Together- Al Green Feel So Close- Calvin Harris Shout- The Isley Brothers This Old Heart Of Mine- The Isley Brothers Billie Jean- Michael Jackson Don’t Stop (Till You Get Enough)- Michael Jackson Human Nature- Michael Jackson The Way You Make Me Feel- Michael Jackson Super Freak- Rick James Boogie Shoes- KC & The Sunshine Band Get Down Tonight- KC & The Sunshine Band Stand By Me- Ben E. King All Of Me- John Legend Stay With You- John Legend Good Golly Miss Molly- Little Richard SOUL/ RAP/ FUNK/ R & B/ DISCO Moves Like Jagger- Maroon 5 Sugar- Maroon 5 24K Magic- Bruno Mars Just The Way You Are- Bruno Mars Locked Out Of Heaven- Bruno Mars Uptown Funk- Bruno Mars & Mark Ronson Hey Ya!- Outkast In The Midnight Hour- Wilson Pickett Mustang Sally- Wilson Pickett That’s How Strong My Love -

In the Studio: the Role of Recording Techniques in Rock Music (2006)

21 In the Studio: The Role of Recording Techniques in Rock Music (2006) John Covach I want this record to be perfect. Meticulously perfect. Steely Dan-perfect. -Dave Grohl, commencing work on the Foo Fighters 2002 record One by One When we speak of popular music, we should speak not of songs but rather; of recordings, which are created in the studio by musicians, engineers and producers who aim not only to capture good performances, but more, to create aesthetic objects. (Zak 200 I, xvi-xvii) In this "interlude" Jon Covach, Professor of Music at the Eastman School of Music, provides a clear introduction to the basic elements of recorded sound: ambience, which includes reverb and echo; equalization; and stereo placement He also describes a particularly useful means of visualizing and analyzing recordings. The student might begin by becoming sensitive to the three dimensions of height (frequency range), width (stereo placement) and depth (ambience), and from there go on to con sider other special effects. One way to analyze the music, then, is to work backward from the final product, to listen carefully and imagine how it was created by the engineer and producer. To illustrate this process, Covach provides analyses .of two songs created by famous producers in different eras: Steely Dan's "Josie" and Phil Spector's "Da Doo Ron Ron:' Records, tapes, and CDs are central to the history of rock music, and since the mid 1990s, digital downloading and file sharing have also become significant factors in how music gets from the artists to listeners. Live performance is also important, and some groups-such as the Grateful Dead, the Allman Brothers Band, and more recently Phish and Widespread Panic-have been more oriented toward performances that change from night to night than with authoritative versions of tunes that are produced in a recording studio.