On Aharon Barak's Activist Image

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Israel: Growing Pains at 60

Viewpoints Special Edition Israel: Growing Pains at 60 The Middle East Institute Washington, DC Middle East Institute The mission of the Middle East Institute is to promote knowledge of the Middle East in Amer- ica and strengthen understanding of the United States by the people and governments of the region. For more than 60 years, MEI has dealt with the momentous events in the Middle East — from the birth of the state of Israel to the invasion of Iraq. Today, MEI is a foremost authority on contemporary Middle East issues. It pro- vides a vital forum for honest and open debate that attracts politicians, scholars, government officials, and policy experts from the US, Asia, Europe, and the Middle East. MEI enjoys wide access to political and business leaders in countries throughout the region. Along with information exchanges, facilities for research, objective analysis, and thoughtful commentary, MEI’s programs and publications help counter simplistic notions about the Middle East and America. We are at the forefront of private sector public diplomacy. Viewpoints are another MEI service to audiences interested in learning more about the complexities of issues affecting the Middle East and US rela- tions with the region. To learn more about the Middle East Institute, visit our website at http://www.mideasti.org The maps on pages 96-103 are copyright The Foundation for Middle East Peace. Our thanks to the Foundation for graciously allowing the inclusion of the maps in this publication. Cover photo in the top row, middle is © Tom Spender/IRIN, as is the photo in the bottom row, extreme left. -

Judicial Review, a Comparative Perspective: Israel, Canada, and the United States

Yeshiva University, Cardozo School of Law LARC @ Cardozo Law Articles Faculty 2010 Judicial Review, a Comparative Perspective: Israel, Canada, and the United States Malvina Halberstam Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://larc.cardozo.yu.edu/faculty-articles Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Malvina Halberstam, Judicial Review, a Comparative Perspective: Israel, Canada, and the United States, 31 Cardozo Law Review 2393 (2010). Available at: https://larc.cardozo.yu.edu/faculty-articles/68 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty at LARC @ Cardozo Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles by an authorized administrator of LARC @ Cardozo Law. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. JUDICIAL REVIEW, A COMPARATIVE PERSPECTIVE: ISRAEL, CANADA, AND THE UNITED STATES INTRODUCTION Malvina Halberstam∗ On April 26, 2009, the Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law hosted a roundtable discussion, Judicial Review, a Comparative Perspective: Israel, Canada, and the United States, with prominent jurists, statesmen, academics, and practicing attorneys.∗∗ The panel was comprised of Justice Morris Fish of the Canadian Supreme Court; Justice Elyakim Rubinstein of the Israeli Supreme Court; Judge Richard Posner of the United States Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit; Hon. Irwin Cotler, a member of the Canadian Parliament and formerly Minister of Justice and Attorney General of Canada; Hon. Michael Eitan, a Minister in the government of Israel, a member of the Knesset (Israeli Parliament), and former chair of the Committee on the Constitution, Law and Justice; Professor Daniel Friedmann, formerly Minister of Justice of Israel, who proposed legislation to remedy what some view as serious problems with judicial review in Israel; Nathan Lewin, one of the most eminent attorneys in the United States, who has argued many cases before the U.S. -

Inventing Judicial Review: Israel and America

INAUGUARL URI AND CAROLINE BAUER MEMORIAL LECTURE INVENTING JUDICIAL REVIEW: ISRAEL AND AMERICA Robert A. Burt* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. THE FIRST GENERATION: TOWARD AN INDEPENDENT JUDICIARY .............................................. 2017 A. The Impact of the 1967 War on Israeli Jurisprudence .................................................... 2027 1. Jurisdiction over the Occupied Territories ....... 2029 2. The Knesset Acts ............................... 2034 B. The Court's Initial Response ......................... 2036 1. Shalit v. Minister of the Interior ................. 2036 2. Bergman v. Minister of Finance .................. 2043 3. Bergman and Marbury .......................... 2047 4. Jurisdiction over the Territories and Marbury .... 2049 II. THE SECOND GENERATION: THE AMERICAN WAY ...... 2051 A. The Definitive Emergence of Judicial Review in A m erica ............................................ 2051 B. The Israeli Supreme Court Charts Its Path ........... 2066 1. Israel's Dred Scott ............................... 2067 2. Judicial Injunctions to Tolerate the Intolerant ... 2077 3. The Promise and Problems of Judicial Independence ................................... 2084 C. The Convergence of Israeli and American Doctrine ... 2091 * Southmayd Professor of Law, Yale University. This Article is an expanded version of the Inaugural Uri and Caroline Bauer Memorial Lecture delivered at the Benjamin N. Car- dozo School of Law of Yeshiva University on October 11, 1988. I am especially indebted to Justice Aharon Barak, Professor Kenneth Mann of the Tel Aviv University Faculty of Law, and Dean Stephen Goldstein of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem Faculty of Law. Although none of them is responsible for the substance of this Article, without their generous assistance it would not have been written. I am also particularly grateful to two Yale Law School students, Stephen Sowle who helped me with the American historical sources and Joel Prager who gave me access to material only available in Hebrew. -

The Saban Forum 2005

The Saban Forum 2005 A U.S.–Israel Dialogue Dealing with 21st Century Challenges Jerusalem, Israel November 11–13, 2005 The Saban Forum 2005 A U.S.–Israel Dialogue Dealing with 21st Century Challenges Jerusalem, Israel November 11–13, 2005 Jaffee Center for Strategic Studies Tel Aviv University Speakers and Chairmen Shai Agassi Shimon Peres Stephen Breyer Itamar Rabinovich David Brooks Aviezer Ravitzky William J. Clinton Condoleezza Rice Hillary Rodham Clinton Haim Saban Avi Dicter Ariel Sharon Thomas L. Friedman Zvi Shtauber David Ignatius Strobe Talbott Moshe Katsav Yossi Vardi Tzipi Livni Margaret Warner Shaul Mofaz James Wolfensohn Letter from the Chairman . 5 List of Participants . 6 Executive Summary . 9 Program Schedule . 19 Proceedings . 23 Katsav Keynote Address . 37 Clinton Keynote Address . 43 Sharon Keynote Address . 73 Rice Keynote Address . 83 Participant Biographies . 89 About the Saban Center . 105 About the Jaffee Center . 106 The ongoing tumult in the Middle East makes continued dialogue between the allied democracies of the United States and Israel all the more necessary and relevant. A Letter from the Chairman In November 2005, we held the second annual Saban Forum in Jerusalem. We had inaugurated the Saban Forum in Washington DC in December 2004 to provide a structured, institutional- ized annual dialogue between the United States and Israel. Each time we have gathered the high- est-level political and policy leaders, opinion formers and intellectuals to define and debate the issues that confront two of the world’s most vibrant democracies: the United States and Israel. The timing of the 2005 Forum could not have been more propitious or tragic. -

The Haredim As a Challenge for the Jewish State. the Culture War Over Israel's Identity

SWP Research Paper Peter Lintl The Haredim as a Challenge for the Jewish State The Culture War over Israel’s Identity Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik German Institute for International and Security Affairs SWP Research Paper 14 December 2020, Berlin Abstract ∎ A culture war is being waged in Israel: over the identity of the state, its guiding principles, the relationship between religion and the state, and generally over the question of what it means to be Jewish in the “Jewish State”. ∎ The Ultra-Orthodox community or Haredim are pitted against the rest of the Israeli population. The former has tripled in size from four to 12 per- cent of the total since 1980, and is projected to grow to over 20 percent by 2040. That projection has considerable consequences for the debate. ∎ The worldview of the Haredim is often diametrically opposed to that of the majority of the population. They accept only the Torah and religious laws (halakha) as the basis of Jewish life and Jewish identity, are critical of democratic principles, rely on hierarchical social structures with rabbis at the apex, and are largely a-Zionist. ∎ The Haredim nevertheless depend on the state and its institutions for safeguarding their lifeworld. Their (growing) “community of learners” of Torah students, who are exempt from military service and refrain from paid work, has to be funded; and their education system (a central pillar of ultra-Orthodoxy) has to be protected from external interventions. These can only be achieved by participation in the democratic process. ∎ Haredi parties are therefore caught between withdrawal and influence. -

Civic Identity in the Jewish State and the Changing Landscape of Israeli Constitutionalism

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont CMC Senior Theses CMC Student Scholarship 2018 Shifting Priorities? Civic Identity in the Jewish State and the Changing Landscape of Israeli Constitutionalism Mohamad Batal Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, and the Law and Politics Commons Recommended Citation Batal, Mohamad, "Shifting Priorities? Civic Identity in the Jewish State and the Changing Landscape of Israeli Constitutionalism" (2018). CMC Senior Theses. 1826. https://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses/1826 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you by Scholarship@Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in this collection by an authorized administrator. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Claremont McKenna College Shifting Priorities? Civic Identity in the Jewish State and the Changing Landscape of Israeli Constitutionalism Submitted To Professor George Thomas by Mohamad Batal for Senior Thesis Spring 2018 April 23, 2018 ii iii iv Abstract: This thesis begins with an explanation of Israel’s foundational constitutional tension—namely, that its identity as a Jewish State often conflicts with liberal- democratic principles to which it is also committed. From here, I attempt to sketch the evolution of the state’s constitutional principles, pointing to Chief Justice Barak’s “constitutional revolution” as a critical juncture where the aforementioned theoretical tension manifested in practice, resulting in what I call illiberal or undemocratic “moments.” More profoundly, by introducing Israel’s constitutional tension into the public sphere, the Barak Court’s jurisprudence forced all of the Israeli polity to confront it. My next chapter utilizes the framework of a bill currently making its way through the Knesset—Basic Law: Israel as the Nation-State of the Jewish People—in order to draw out the past and future of Israeli civic identity. -

Zionism & Israel As the Nation-State of the Jewish People

Zionism & Israel as the Nation-State of the Jewish People CUTTING THROUGH THE CONFUSION BY GOING BACK TO BASICS A Resource for the Global Jewish World Zionism & Israel as the Nation-State of the Jewish People CUTTING THROUGH THE CONFUSION BY GOING BACK TO BASICS A Resource by The Israel Forever Foundation THE PROBLEM The debates surrounding Zionism, Israel, and the legitimacy of a Nation State for the Jewish People seem never ending. The foundations on which the Jewish State was founded are constantly being questioned – both by the anti-Israel movement as well as within the Jewish world. Is Zionism racism? Is the word “Zionist” an insult? More and more people seem to think so. Social media’s magnification of individual voices has blurred the lines between what were until very recently extremist views one would not publicly express and narrative that is being expressed on college campuses, political pulpits and even mainstream media. Are we equipped to answer these accusations? Do we want to? How can we prepare the next generations to handle what is coming? In a time of pluralism and globalism, is the Jewish State legitimate? The legitimacy of the Jewish State has been questioned since (before) her establishment. The recent passing of Israel’s Nation State Law has been the impetus for renewed questioning. Many in the Jewish world have felt uneasy about the law, fearing it undermines the inherent pluralism of the Jewish State. What is the balance between Jewish Nationalism, Israel as a homeland for the Jewish People and Israel as a modern, liberal and pluralist country? What are the concerns? How should they be addressed? Confusion within the Jewish world We know that antisemitism is on the rise. -

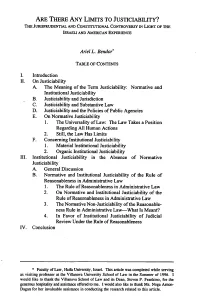

Are There Any Limits to Justiciability? the Jurisprudential and Constitutional Controversy in Light of the Israeli and American Experience

ARE THERE ANY LIMITS TO JUSTICIABILITY? THE JURISPRUDENTIAL AND CONSTITUTIONAL CONTROVERSY IN LIGHT OF THE ISRAELI AND AMERICAN EXPERIENCE Ariel L. Bendor" TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction II. On Justiciability A. The Meaning of the Term Justiciability: Normative and Institutional Justiciability B. Justiciability and Jurisdiction C. Justiciability and Substantive Law D. Justiciability and the Policies of Public Agencies E. On Normative Justiciability 1. The Universality of Law: The Law Takes a Position Regarding All Human Actions 2. Still, the Law Has Limits F. Concerning Institutional Justiciability I. Material Institutional Justiciability 2. Organic Institutional Justiciability III. Institutional Justiciability in the Absence of Normative Justiciability A. General Discussion B. Normative and Institutional Justiciability of the Rule of Reasonableness in Administrative Law 1. The Rule of Reasonableness in Administrative Law 2. On Normative and Institutional Justiciability of the Rule of Reasonableness in Administrative Law 3. The Normative Non-Justiciability of the Reasonable- ness Rule in Administrative Law-What Is Meant? 4. In Favor of Institutional Justiciability of Judicial Review Under the Rule of Reasonableness IV. Conclusion * Faculty of Law, Haifa University, Israel. This article was completed while serving as visiting professor at the Villanova University School of Law in the Summer of 1996. I would like to thank the Villanova School of Law and its Dean, Steven P. Frankino, for the generous hospitality and assistance offered to me. I would also like to thank Ms. Noga Arnon- Dagan for her invaluable assistance in conducting the research related to this article. IND. INT'L & COMP. L. REV. [Vol. 7:2 I. INTRODUCTION Justiciability deals with the boundaries of law and adjudication. -

The Judicial Discretion of Justice Aharon Barak

Tulsa Law Review Volume 47 Issue 2 Symposium: Justice Aharon Barak Fall 2011 The Judicial Discretion of Justice Aharon Barak Ariel L. Bendor Zeev Segal Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.utulsa.edu/tlr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Ariel L. Bendor, & Zeev Segal, The Judicial Discretion of Justice Aharon Barak, 47 Tulsa L. Rev. 465 (2013). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.utulsa.edu/tlr/vol47/iss2/10 This Legal Scholarship Symposia Articles is brought to you for free and open access by TU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Tulsa Law Review by an authorized editor of TU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Bendor and Segal: The Judicial Discretion of Justice Aharon Barak THE JUDICIAL DISCRETION OF JUSTICE AHARON BARAK Ariel L. Bendor* & Zeev Segal" Aharon Barak has fervent admirers as well as harsh critics. An extraordinarily large percentage of Israelis claim to be knowledgeable about Barak and his pursuits. Many Israelis seem to have an opinion about him. No other judge in Israel approaches this level of public renown. This may seem surprising, given that Barak is not a politician, nor is he in the habit of granting interviews. On the rare occasions he appears in public, he reads from prepared notes. Most significantly, he enjoys this status in the wake of professional achievements that, by and large, the public knows nothing about. A clear, accessible presentation of Barak's views, as they emerged from our talks, will not only provide a better understanding of his opinions, but will allow a serious critical accounting of their breadth, flaws, and weaknesses. -

A View on Law, Adjudication and Judicial Activism

ON SOCIETY, LAW AND JUDGING Montesquieu Lecture 2010 Aharon Barak A. On Society Law is everywhere - though law is not everything. Law is everywhere in the sense that all human conduct is the subject of a legal norm. Even when an activity – such as friendship– is controlled by the autonomy of individual will, that autonomy exists within the law. Without it, everyone would have the freedom to invade that area. However, law is not everything. There is religion, and morals. Even the universality of law is not for the law's sake. The law is a means to organize life between the members of a given society at a given time. The universality of law is thus intended to maintain life in society. The law is a tool that allows society to function. Each society’s members must determine the appropriate character of relationships in that society. Naturally, the different members of society have different views regarding what are appropriate societal relations. There are those who would like to see human rights as the focus of and the foundation of these relationships. Others see belief in God and the observing of his commandments as the necessary guide. There are those who would emphasize the good of the state as a whole, and there are those who concentrate on the good of the individual. Moreover, in most cases, society wishes to attain most of its objectives while they remain uninterested in taking a clear stand on the spectrum. It is necessary to reach a national compromise when choosing between values and principles. -

Professor Aharon Barak President of the Israeli Supreme Court (Ret.), Idc Herzliya

THE 23RD HUGO L. BLACK LECTURE ON FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION HUMAN DIGNITY AND FREE SPEECH Delivered by PROFESSOR AHARON BARAK PRESIDENT OF THE ISRAELI SUPREME COURT (RET.), IDC HERZLIYA October 8, 2013 8 p.m. Memorial Chapel Wesleyan University Middletown, Connecticut Commentary by Eric Stephen ’13 THE HONORABLE AHARON BARAK, FORMER PRESIDENT OF THE SUPREME COURT OF ISRAEL The honorable Aharon Barak is the former President of the Supreme Court of Israel, credited as “the most influential Justice Israel has ever known”. 1 Born in 1936 in Kaunas, Lithuania, President Barak and his family survived the Holocaust for three years in the Kovno ghetto before immigrating to Israel in 1947, eventually settling in Jerusalem. Barak received his Bachelor of Laws in 1958 from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem before being drafted into the Israeli Defense Forces from 1958 to 1960. After his discharge, Barak went on to receive his doctorate in 1963 and was appointed a professor at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem in 1968. He then served as the Attorney General of Israel from 1975 until hiss appointment to the Supreme Court in 1978. There, he served as a Justice between 1978 and 1995 when he began his service as the Court’s President until his retirement in 2006. Currently, President Barak is a Visiting Professor of Law and the Gruber Global Constitutionalism Fellow at Yale Law School. As an honored speaker for the Hugo L. Black Lecture on Freedom of Expression, President Barak will explore the interrelationship between the freedom of speech and human dignity in a democratic society. -

Camp David 25Th Anniversary Forum

SPECIAL CONFERENCE SERIES CAMP DAVID 25TH ANNIVERSARY FORUM WOODROW WILSON INTERNATIONAL CENTER FOR SCHOLARS WASHINGTON, D.C. SEPTEMBER 17, 2003 Waging Peace. Fighting Disease. Building Hope. THE CARTER CENTER STRIVES TO RELIEVE SUFFERING BY ADVANCING PEACE AND HEALTH WORLDWIDE; IT SEEKS TO PREVENT AND RESOLVE CONFLICTS, ENHANCE FREEDOM AND DEMOCRACY, AND PROTECT AND PROMOTE HUMAN RIGHTS WORLDWIDE. CAMP DAVID 25TH ANNIVERSARY FORUM WOODROW WILSON INTERNATIONAL CENTER FOR SCHOLARS WASHINGTON, D.C. SEPTEMBER 17, 2003 ONE COPENHILL 453 FREEDOM PARKWAY ATLANTA, GA 30307 (404) 420-5185 FAX (404) 420-3862 WWW.CARTERCENTER.ORG JANUARY 2004 THE CARTER CENTER CAMP DAVID 25TH ANNIVERSARY FORUM TABLE OF CONTENTS Participants . .3 Morning Session . .4 Luncheon Address . .43 Question-and-Answer Session . .48 Afternoon Session . .51 All photos by William Fitz-Patrick 2 THE CARTER CENTER CAMP DAVID 25TH ANNIVERSARY FORUM THE CARTER CENTER CAMP DAVID 25TH ANNIVERSARY FORUM WOODROW WILSON INTERNATIONAL CENTER FOR SCHOLARS WASHINGTON, D.C. SEPTEMBER 17, 2003 Participants Title at the time of negotiations Jimmy Carter U.S. President Walter Mondale U.S. Vice President William Quandt U.S. National Security Council Elyakim Rubinstein Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Israel Zbigniew Brzezinski U.S. National Security Adviser to the President Aharon Barak Attorney General and Supreme Court Member-Designate, Israel Harold Saunders U.S. Assistant Secretary of State for Near East Affairs Hamilton Jordan U.S. Chief of Staff to the President Jody Powell U.S. Press Secretary to the President Samuel Lewis U.S. Ambassador to Israel Hermann Eilts U.S. Ambassador to Egypt Osama el-Baz Foreign Policy Adviser to the President of Egypt (by videoconference from Cairo) Boutros Boutros-Ghali Minister of State for Foreign Affairs, Egypt (by recorded message from Paris via CNN) Master of Ceremonies Lee Hamilton Director, Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars (former Member of Congress) 3 THE CARTER CENTER CAMP DAVID 25TH ANNIVERSARY FORUM MORNING SESSION Lee Hamilton: Good morning to all of you.