Arxiv:1605.00579V1 [Astro-Ph.EP] 2 May 2016 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dustin M. Schroeder

Dustin M. Schroeder Assistant Professor of Geophysics Department of Geophysics, School of Earth, Energy, and Environmental Sciences 397 Panama Mall, Mitchell Building 361, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 94305 [email protected], 440.567.8343 EDUCATION 2014 Jackson School of Geosciences, University of Texas, Austin, TX Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.) in Geophysics 2007 Bucknell University, Lewisburg, PA Bachelor of Science in Electrical Engineering (B.S.E.E.), departmental honors, magna cum laude Bachelor of Arts (B.A.) in Physics, magna cum laude, minors in Mathematics and Philosophy PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE 2016 – present Assistant Professor of Geophysics, Stanford University 2017 – present Assistant Professor (by courtesy) of Electrical Engineering, Stanford University 2020 – present Center Fellow (by courtesy), Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment 2020 – present Faculty Affiliate, Stanford Institute for Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence 2021 – present Senior Member, Kavli Institute for Particle Astrophysics and Cosmology 2016 – 2020 Faculty Affiliate, Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment 2014 – 2016 Radar Systems Engineer, Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology 2012 Graduate Researcher, Applied Physics Laboratory, Johns Hopkins University 2008 – 2014 Graduate Researcher, University of Texas Institute for Geophysics 2007 – 2008 Platform Hardware Engineer, Freescale Semiconductor SELECTED AWARDS 2021 Symposium Prize Paper Award, IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Society 2020 Excellence in Teaching Award, Stanford School of Earth, Energy, and Environmental Sciences 2019 Senior Member, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers 2018 CAREER Award, National Science Foundation 2018 LInC Fellow, Woods Institute, Stanford University 2016 Frederick E. Terman Fellow, Stanford University 2015 JPL Team Award, Europa Mission Instrument Proposal 2014 Best Graduate Student Paper, Jackson School of Geosciences 2014 National Science Olympiad Heart of Gold Award for Service to Science Education 2013 Best Ph.D. -

2018: Aiaa-Space-Report

AIAA TEAM SPACE TRANSPORTATION DESIGN COMPETITION TEAM PERSEPHONE Submitted By: Chelsea Dalton Ashley Miller Ryan Decker Sahil Pathan Layne Droppers Joshua Prentice Zach Harmon Andrew Townsend Nicholas Malone Nicholas Wijaya Iowa State University Department of Aerospace Engineering May 10, 2018 TEAM PERSEPHONE Page I Iowa State University: Persephone Design Team Chelsea Dalton Ryan Decker Layne Droppers Zachary Harmon Trajectory & Propulsion Communications & Power Team Lead Thermal Systems AIAA ID #908154 AIAA ID #906791 AIAA ID #532184 AIAA ID #921129 Nicholas Malone Ashley Miller Sahil Pathan Joshua Prentice Orbit Design Science Science Science AIAA ID #921128 AIAA ID #922108 AIAA ID #761247 AIAA ID #922104 Andrew Townsend Nicholas Wijaya Structures & CAD Trajectory & Propulsion AIAA ID #820259 AIAA ID #644893 TEAM PERSEPHONE Page II Contents 1 Introduction & Problem Background2 1.1 Motivation & Background......................................2 1.2 Mission Definition..........................................3 2 Mission Overview 5 2.1 Trade Study Tools..........................................5 2.2 Mission Architecture.........................................6 2.3 Planetary Protection.........................................6 3 Science 8 3.1 Observations of Interest.......................................8 3.2 Goals.................................................9 3.3 Instrumentation............................................ 10 3.3.1 Visible and Infrared Imaging|Ralph............................ 11 3.3.2 Radio Science Subsystem................................. -

7'Tie;T;E ~;&H ~ T,#T1tmftllsieotog

7'tie;T;e ~;&H ~ t,#t1tMftllSieotOg, UCLA VOLUME 3 1986 EDITORIAL BOARD Mark E. Forry Anne Rasmussen Daniel Atesh Sonneborn Jane Sugarman Elizabeth Tolbert The Pacific Review of Ethnomusicology is an annual publication of the UCLA Ethnomusicology Students Association and is funded in part by the UCLA Graduate Student Association. Single issues are available for $6.00 (individuals) or $8.00 (institutions). Please address correspondence to: Pacific Review of Ethnomusicology Department of Music Schoenberg Hall University of California Los Angeles, CA 90024 USA Standing orders and agencies receive a 20% discount. Subscribers residing outside the U.S.A., Canada, and Mexico, please add $2.00 per order. Orders are payable in US dollars. Copyright © 1986 by the Regents of the University of California VOLUME 3 1986 CONTENTS Articles Ethnomusicologists Vis-a-Vis the Fallacies of Contemporary Musical Life ........................................ Stephen Blum 1 Responses to Blum................. ....................................... 20 The Construction, Technique, and Image of the Central Javanese Rebab in Relation to its Role in the Gamelan ... ................... Colin Quigley 42 Research Models in Ethnomusicology Applied to the RadifPhenomenon in Iranian Classical Music........................ Hafez Modir 63 New Theory for Traditional Music in Banyumas, West Central Java ......... R. Anderson Sutton 79 An Ethnomusicological Index to The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, Part Two ............ Kenneth Culley 102 Review Irene V. Jackson. More Than Drumming: Essays on African and Afro-Latin American Music and Musicians ....................... Norman Weinstein 126 Briefly Noted Echology ..................................................................... 129 Contributors to this Issue From the Editors The third issue of the Pacific Review of Ethnomusicology continues the tradition of representing the diversity inherent in our field. -

Monday, November 13, 2017 WHAT DOES IT MEAN to BE HABITABLE? 8:15 A.M. MHRGC Salons ABCD 8:15 A.M. Jang-Condell H. * Welcome C

Monday, November 13, 2017 WHAT DOES IT MEAN TO BE HABITABLE? 8:15 a.m. MHRGC Salons ABCD 8:15 a.m. Jang-Condell H. * Welcome Chair: Stephen Kane 8:30 a.m. Forget F. * Turbet M. Selsis F. Leconte J. Definition and Characterization of the Habitable Zone [#4057] We review the concept of habitable zone (HZ), why it is useful, and how to characterize it. The HZ could be nicknamed the “Hunting Zone” because its primary objective is now to help astronomers plan observations. This has interesting consequences. 9:00 a.m. Rushby A. J. Johnson M. Mills B. J. W. Watson A. J. Claire M. W. Long Term Planetary Habitability and the Carbonate-Silicate Cycle [#4026] We develop a coupled carbonate-silicate and stellar evolution model to investigate the effect of planet size on the operation of the long-term carbon cycle, and determine that larger planets are generally warmer for a given incident flux. 9:20 a.m. Dong C. F. * Huang Z. G. Jin M. Lingam M. Ma Y. J. Toth G. van der Holst B. Airapetian V. Cohen O. Gombosi T. Are “Habitable” Exoplanets Really Habitable? A Perspective from Atmospheric Loss [#4021] We will discuss the impact of exoplanetary space weather on the climate and habitability, which offers fresh insights concerning the habitability of exoplanets, especially those orbiting M-dwarfs, such as Proxima b and the TRAPPIST-1 system. 9:40 a.m. Fisher T. M. * Walker S. I. Desch S. J. Hartnett H. E. Glaser S. Limitations of Primary Productivity on “Aqua Planets:” Implications for Detectability [#4109] While ocean-covered planets have been considered a strong candidate for the search for life, the lack of surface weathering may lead to phosphorus scarcity and low primary productivity, making aqua planet biospheres difficult to detect. -

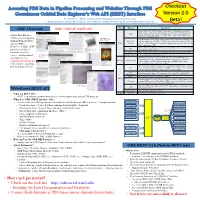

Accessing Pds Data in Pipeline Processing and Web Sites Through Pds Geosciences Orbital Data Explorer’S Web-Based Api (Rest) Interface

45th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference (2014) 1026.pdf ACCESSING PDS DATA IN PIPELINE PROCESSING AND WEB SITES THROUGH PDS GEOSCIENCES ORBITAL DATA EXPLORER’S WEB-BASED API (REST) INTERFACE. K. J. Bennett, J. Wang, D. Scholes, Washington University in St. Louis, 1 Brookings Drive, Campus Box 1169, St. Louis, Missouri, 63130, {bennett, wang, sholes}@wunder.wustl.edu. Introduction: The Orbital Data Explorer (ODE) is tem (RSS). a web-based search tool (http://ode.rsl.wustl.edu) de- High Resolution Stereo Camera (HRSC), Mars Advanced Radar for Subsurface and Iono- veloped at NASA’s Planetary Data System’s (PDS) sphere Sounding (MARSIS), OMEGA Geosciences Node (http://pds-geosciences.wustl.edu/). Mars Express (Observatoire Mineralogie, Eau, Glaces, Through ODE, users can search, browse, and download Activite) Visible and Infrared Mineralogical a wide range of PDS Mars, Moon, Mercury, and Venus Mapping Spectrometer, and Planetary Fourier Spectrometer (PFS). data ([1,2,3,4]). Mars Orbiter Laser Altimeter (MOLA), and Mars Global In the fall of 2012, the Geosciences node intro- MOC Narrow Angle (NA) and Wide Angle Surveyor (MGS) duced a simple web-based API that allows non-PDS (WA) cameras. Gamma Ray Spectrometer (GRS) and Thermal web and processing tools to search for PDS products, Odyssey Emission Imaging System (THEMIS) obtain meta-data about those products, and download Viking Orbiter Visual Imaging Subsystem Camera A/B the products stored in ODE’s meta-data database. The Gamma Ray Spectrometer (GRS), Radio Sci- first version is now used by several teams in periodic MESSENGER ence Subsystem (RSS), Neutron Spectrometer processing and web sites. -

Abstracts of the 50Th DDA Meeting (Boulder, CO)

Abstracts of the 50th DDA Meeting (Boulder, CO) American Astronomical Society June, 2019 100 — Dynamics on Asteroids break-up event around a Lagrange point. 100.01 — Simulations of a Synthetic Eurybates 100.02 — High-Fidelity Testing of Binary Asteroid Collisional Family Formation with Applications to 1999 KW4 Timothy Holt1; David Nesvorny2; Jonathan Horner1; Alex B. Davis1; Daniel Scheeres1 Rachel King1; Brad Carter1; Leigh Brookshaw1 1 Aerospace Engineering Sciences, University of Colorado Boulder 1 Centre for Astrophysics, University of Southern Queensland (Boulder, Colorado, United States) (Longmont, Colorado, United States) 2 Southwest Research Institute (Boulder, Connecticut, United The commonly accepted formation process for asym- States) metric binary asteroids is the spin up and eventual fission of rubble pile asteroids as proposed by Walsh, Of the six recognized collisional families in the Jo- Richardson and Michel (Walsh et al., Nature 2008) vian Trojan swarms, the Eurybates family is the and Scheeres (Scheeres, Icarus 2007). In this theory largest, with over 200 recognized members. Located a rubble pile asteroid is spun up by YORP until it around the Jovian L4 Lagrange point, librations of reaches a critical spin rate and experiences a mass the members make this family an interesting study shedding event forming a close, low-eccentricity in orbital dynamics. The Jovian Trojans are thought satellite. Further work by Jacobson and Scheeres to have been captured during an early period of in- used a planar, two-ellipsoid model to analyze the stability in the Solar system. The parent body of the evolutionary pathways of such a formation event family, 3548 Eurybates is one of the targets for the from the moment the bodies initially fission (Jacob- LUCY spacecraft, and our work will provide a dy- son and Scheeres, Icarus 2011). -

Enceladus Life Finder: the Search for Life in a Habitable Moon

Geophysical Research Abstracts Vol. 17, EGU2015-14923, 2015 EGU General Assembly 2015 © Author(s) 2015. CC Attribution 3.0 License. Enceladus life finder: the search for life in a habitable moon. Jonathan Lunine (1), Hunter Waite (2), Frank Postberg (3), Linda Spilker (4), and Karla Clark (4) (1) Center for Radiophysics and Space Research, Cornell University, Ithaca ([email protected]), (2) Southwest Research Institute,San Antonio, ( [email protected]), (3) U. Stuttgart, Stuttgart, ([email protected]), (4) Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena CA 91125, ( [email protected]) Is there life elsewhere in the solar system? Guided by the principle that we can most easily recognize life as we know it—life that requires liquid water—Enceladus is particularly attractive because liquid water from its deep interior is actively erupting into space, making sampling of the interior straightforward. The Cassini Saturn Orbiter has provided the motivation. In particular, at high resolution, spatial coincidences between individual geysers and small-scale hot spots revealed the liquid reservoir supplying the eruptions to be not in the near-surface but deeper within the moon [1], putting on a firm foundation the principle that sampling the plume allows us to know the composition of the ocean. Sensitive gravity and topography measurements established the location and dimensions of that reservoir: ∼ 35 km beneath the SPT ice shell and extending out to at least 50 degrees latitude, implying an interior ocean large enough to have been stable over geologic time [2]. The Cassini ion neutral mass spectrometer (INMS) discovered organic and nitrogen-bearing molecules in the plume vapour, and the Cosmic Dust Analyser (CDA) detected salts in the plume icy grains, arguing strongly for ocean water being in con-tact with a rocky core [3], [4]. -

The Cassini Ion and Neutral Mass Spectrometer (Inms) Investigation

THE CASSINI ION AND NEUTRAL MASS SPECTROMETER (INMS) INVESTIGATION 1, 2 3 4 J. H. WAITE ∗, JR., W. S. LEWIS ,W.T. KASPRZAK ,V.G. ANICICH , B. P. BLOCK1,T.E. CRAVENS5,G.G. FLETCHER1,W.-H. IP6,J.G. LUHMANN7, R. L. MCNUTT8,H.B. NIEMANN3,J.K.PAREJKO1,J.E. RICHARDS3, R. L. THORPE2, E. M. WALTER1 and R. V. YELLE9 1University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, U.S.A. 2Southwest Research Institute, San Antonio, TX, U.S.A. 3NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, MD, U.S.A. 4NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, CA, U.S.A. 5University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS, U.S.A. 6National Central University, Chung-Li, Taiwan 7University of California, Berkeley, CA, U.S.A. 8Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, Laurel, MD, U.S.A. 9University of Arizona, Flagstaff, AZ, U.S.A. (∗Author for correspondence, E-mail: [email protected]) (Received 13 August 1998; Accepted in final form 17 February 2004) Abstract. The Cassini Ion and Neutral Mass Spectrometer (INMS) investigation will determine the mass composition and number densities of neutral species and low-energy ions in key regions of the Saturn system. The primary focus of the INMS investigation is on the composition and structure of Titan’s upper atmosphere and its interaction with Saturn’s magnetospheric plasma. Of particular interest is the high-altitude region, between 900 and 1000 km, where the methane and nitrogen photochemistry is initiated that leads to the creation of complex hydrocarbons and nitriles that may eventually precipitate onto the moon’s surface to form hydrocarbon–nitrile lakes or oceans. -

Valuing Life Detection Missions Edwin S

Valuing life detection missions Edwin S. Kite* (University of Chicago), Eric Gaidos (University of Hawaii), Tullis C. Onstott (Princeton University). * [email protected] Recent discoveries imply that Early Mars was habitable for life-as-we-know-it (Grotzinger et al. 2014); that Enceladus might be habitable (Waite et al. 2017); and that many stars have Earth- sized exoplanets whose insolation favors surface liquid water (Dressing & Charbonneau 2013, Gaidos 2013). These exciting discoveries make it more likely that spacecraft now under construction – Mars 2020, ExoMars rover, JWST, Europa Clipper – will find habitable, or formerly habitable, environments. Did these environments see life? Given finite resources ($10bn/decade for the US1), how could we best test the hypothesis of a second origin of life? Here, we first state the case for and against flying life detection missions soon. Next, we assume that life detection missions will happen soon, and propose a framework (Fig. 1) for comparing the value of different life detection missions: Scientific value = (Reach × grasp × certainty × payoff) / $ (1) After discussing each term in this framework, we conclude that scientific value is maximized if life detection missions are flown as hypothesis tests. With hypothesis testing, even a nondetection is scientifically valuable. Should the US fly more life detection missions? Once a habitable environment has been found and characterized, life detection missions are a logical next step. Are we ready to do this? The case for emphasizing habitable environments, not life detection: Our one attempt to detect life, Viking, is viewed in hindsight as premature or at best uncertain. In-space life detection experiments are expensive. -

2015 October

TTSIQ #13 page 1 OCTOBER 2015 www.nasa.gov/press-release/nasa-confirms-evidence-that-liquid-water-flows-on-today-s-mars Flash! Sept. 28, 2015: www.space.com/30674-flowing-water-on-mars-discovery-pictures.html www.space.com/30673-water-flows-on-mars-discovery.html - “boosting odds for life!” These dark, narrow, 100 meter~yards long streaks called “recurring slope lineae” flowing downhill on Mars are inferred to have been formed by contemporary flowing water www.space.com/30683-mars-liquid-water-astronaut-exploration.html INDEX 2 Co-sponsoring Organizations NEWS SECTION pp. 3-56 3-13 Earth Orbit and Mission to Planet Earth 13-14 Space Tourism 15-20 Cislunar Space and the Moon 20-28 Mars 29-33 Asteroids & Comets 34-47 Other Planets & their moons 48-56 Starbound ARTICLES & ESSAY SECTION pp 56-84 56 Replace "Pluto the Dwarf Planet" with "Pluto-Charon Binary Planet" 61 Kepler Shipyards: an Innovative force that could reshape the future 64 Moon Fans + Mars Fans => Collaboration on Joint Project Areas 65 Editor’s List of Needed Science Missions 66 Skyfields 68 Alan Bean: from “Moonwalker” to Artist 69 Economic Assessment and Systems Analysis of an Evolvable Lunar Architecture that Leverages Commercial Space Capabilities and Public-Private-Partnerships 71 An Evolved Commercialized International Space Station 74 Remembrance of Dr. APJ Abdul Kalam 75 The Problem of Rational Investment of Capital in Sustainable Futures on Earth and in Space 75 Recommendations to Overcome Non-Technical Challenges to Cleaning Up Orbital Debris STUDENTS & TEACHERS pp 85-96 Past TTSIQ issues are online at: www.moonsociety.org/international/ttsiq/ and at: www.nss.org/tothestarsOO TTSIQ #13 page 2 OCTOBER 2015 TTSIQ Sponsor Organizations 1. -

CAROL PATY [email protected] 1 Associate Professor Robert D. Clark

CAROL PATY [email protected] Associate Professor Robert D. Clark Honors College & Department of Earth Sciences 1293 University of Oregon Eugene, OR 97403-1293 Educational Background: B.A. Physics & Astronomy 2001 Bryn Mawr College Ph.D. Earth & Space Sciences 2006 University of Washington (Advisor: R. Winglee) Employment History: Undergraduate Teaching Assistant, Bryn Mawr College, Physics 1998-2001 Graduate Teaching Assistant, University of Washington, Earth & Space Sciences 2002-2005 Graduate Research Assistant, University of Washington, Earth & Space Sciences 2001-2006 Instructor, Chautauqua Course on Space Weather & Planetary Magnetospheres 2006 (Summer) Postdoctoral Researcher, Southwest Research Institute, Space Science & Engineering 2006-2008 Assistant Professor, Georgia Institute of Technology, Earth & Atmospheric Science 2008-2014 Associate Professor, Georgia Institute of Technology, Earth & Atmospheric Science 2014-2018 Associate Professor, University of Oregon, Clark Honors College & Earth Sciences 2018-present Current Research Interests: Space Plasma Physics, Planetary Magnetospheres, Planetary Upper Atmospheres/Ionospheres, Icy Satellites, Dusty Plasmas, Mars Atmospheric Evolution, Astrobiology, Mission Planning Activities (Cassini, Jupiter Icy Moon Explorer: JUICE, Europa Clipper Mission, Trident, Odyssey PMCS) Synergistic Activities: National Academy of Sciences – Ocean Worlds and Dwarf Planets Panel for the ‘Planetary Science and Astrobiology Decadal Survey 2023-2032’ October 2020 – present Icarus Editor 2017-present Outer -

ODE Overview Web-Based

Checkout Version 2.0 K. J. Bennett, J. Wang, and D. Scholes, Washington University in St. Louis, 1 Brookings Drive, Campus Box 1169, St. Louis, Missouri, 63130, {bennett, wang , scholes}@wunder.wustl.edu Beta! ODE Overview http://ode.rsl.wustl.edu/ Planet Mission Instrument Shallow Radar (SHARAD), Compact Reconnaissance Imaging Spectrometer for Mars (CRISM), High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE), Context MRO Orbital Data Explorer Imager (CTX), Mars Color Imager (MARCI), Mars Climate Sounder (MCS), and Radio Science Subsystem (RSS). (ODE) was developed by RETRIEVE and High Resolution Stereo Camera (HRSC), Mars Advanced Radar for Subsurface and NASA’s Planetary Data View Products ESA’s Mars Ionosphere Sounding (MARSIS), OMEGA (Observatoire Mineralogie, Eau, Glaces, System (PDS)’s Mars Express Activite) Visible and Infrared Mineralogical Mapping Spectrometer, and Planetary Fourier Spectrometer (PFS). Geosciences Node. ODE Mars Orbiter Laser Altimeter (MOLA), and Mars Orbiter Camera (MOC) Narrow MGS provides web-based Angle and Wide Angle cameras. functions to search, Odyssey Thermal Emission Imaging System (THEMIS), Gamma Ray Spectrometer (GRS). retrieve, and download SEARCH for Viking Orbiter 1/2 Visual Imaging Subsystem Camera A/B Products data from multiple GRS, RSS, Neutron Spectrometer (NS), X-Ray Spectrometer (XRS), Mercury Atmospheric and Surface Composition Spectrometer (MASCS), Mercury Laser Mercury MESSENGER missions and instruments Altimeter (MLA), and Mercury Dual Imaging System (MDIS) Narrow Angle in the rapidly