Rattling Chains and Dreadful Noises: Customs and Arts of Halloween

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

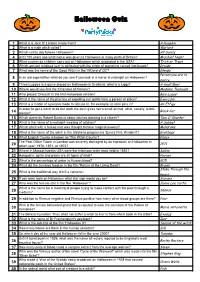

Halloween Quiz

Halloween Quiz 1 What is a Jack O' Lantern made from? A Pumpkin 2 What is a male witch called? Warlock 3 Which saints day follows Halloween? All Saints 4 Until 100 years ago what name was given to Halloween in many parts of Britain? Mischief Night 5 What custom do children carry out on Halloween which originated in the USA? Trick or Treat 6 Which ancient religious sect is attributed with the origin of pumpkins carved into heads? Druids 7 What was the name of the Good Witch in the 'Wizard of Oz'? Glenda Person you are to 8 In an old superstition what do you see if you look in a mirror at midnight on Halloween? marry 9 Three Luggies is a game played on Halloween in Scotland, what is a luggy? A small Bowl 10 Where would you find the 'Chamber of Horrors'? Madame Tussauds 11 Who played 'Dracula' in the first Hollywood version? Bela Lugosi 12 What is the name of the practice of expelling evil spirits from a person or place? Exorcism 13 What is a model of a person made to ridicule or, for example, to stick pins in? An Effigy In order to get a witch to do her work the devil gives her a small animal, what, usually, is this Black Cat 14 animal? 15 Which poem by Robert Burns is about witches dancing in a church? Tam O'Shanter 16 What is the name of a midnight meeting of witches? A Sabbat 17 Which plant with a forked root was thought to have magical powers? Mandrake 18 What is the name of the witch in the childrens programme 'Emu's Pink Windmill'? Grotbags 19 What English County is known as 'The Witch County'? Essex The Post Office Tower in London -

Attractions in Bergen – Opening Hours

OFFICIAL GUIDE FOR BERGEN ENGLISH BERGEN CHRISTMAS & NEW YEAR’S IN BERGEN 2018 2018 © Bergen Reiselivslag / Christer Rønnestad – visitBergen.com PLAN & BOOK: visitBergen.com World Heritage City 2 WELCOME INFORMATION 3 © Bergen Reiselivslag / Robin Strand – visitBergen.com © Bergen Reiselivslag / Robin Strand – visitBergen.com Welcome to Christmas time in Bergen! Calendar Whether you’re spending Christmas or carolling in their neighbourhood. In New Year’s here, we hope you’ll enjoy Bergen this is traditionally done by kids Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Sunday your stay! on New Year’s Eve (nyttårsbukk). There is 17. Dec. 18. Dec. 19. Dec. 20. Dec. 21. Dec. 22. Dec. 23. Dec. Every country has its own set of traditions (or was) an adult version of this tradition and Christmas in Norway might be where people dress up to avoid being different from what you’re familiar with. recognised and visit their neighbours and Norwegian Christmas is all about family friends, asking for drinks. Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Sunday and traditions! To most Norwegians Jul Nyttårsaften (New Year’s Eve) is 24. Dec. 25. Dec. 26. Dec. 27. Dec. 28. Dec. 29. Dec. 30. Dec. means family time – the Scandinavian celebrated with a huge dinner with your concept of hygge is important. On family or friends, and celebrated with Christmas Eve we celebrate with fi reworks, either at home or on the traditional food – usually pinnekjøtt, town. January 1 is a day of relaxation, Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Sunday lutefi sk or ribbe – and opening of restitution and refl ection before heading Christmas presents (not on Christmas back to work on January 2. -

Puck of Pook's Hill

Puck Pook^mU IM: .111 %^ ,,>€ >'!' .(!';: •;;,.* "! #' k4 Cornell HmvetJjsitg ^ibiJ^tg GOLDWiN Smith Hall FROM THE FUND GIVEN BY C$o(&tniit Smtth 1909 Cornell University Library PR4854.P97 1906 Puck of Pook's Hill. 3 1924 014 173 995 Cornell University Library The original of tliis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/cletails/cu31924014173995 Puck of Pook'g Hill Books by Rudyarb mpling Actions and REAcnoNa Light That FAttED, The Brushwood Boy, The Many Inventions Captains Courageous Naulahka, The (With Collected Verse Wolcott Balestier) Day's Work, The Plain Tales From the Departmental Ditties Hills AND Ballads and Bar- Puck of Pook's Hill rack-Room Ballads Rewards and Fairies Diversity of Crea- Rtjdyard Kipling's tures, A Verse: Inclusive Edi- Eyes of Asia, The tion, 1885-1918 Feet of the Young Sea, Warfare Men, The Seven Seas, The Five Nations, The Soldier Stories France at War Fringes ok the Fleet Soldiers Three, The From Sea to Sea Story of the Gadsbys, History op England, A AND In Black and Jungle Book, The White Jungle Book, Second Song of the English^ A Just So Song Book Songs from Books Just So Stories Stalky & Co. Kim They Kipling Stories and trafncs Poems E ery Child and discover- Should Know IES Kipling Birthday Book, Under the Deodars, The The Phantom 'Rick- Letters of Travel shaw, AND Wee Willie Life's Handicap: Being WiNKIE Stories of Mine Own With the Night Mail People Years Between, The CONTENTS PUCK OF POOR'S HILL PUCK'S SONG See you the dimpled track that runs. -

Ritual Examples of Conflicts Secret

Ritual Well Trolls can be driven off by draining the well or leave it unused for six months. If the troll can be lured CHARACTERISTICS out of the well, it can be attacked and killed in the same • Might 5 (troll 7) Body Control 6 manner as humans. It is said that soap also works • Magic 6 Manipulation 4 (hag 8) Fear 1 against the Troll in the Well. The man in the well can be banished by having the children of the area to cronfront their fear of the well, COMBAT or by having a person defeat their reflection in the ATTACK DAMAGE RANGE water. The troll’s long 2 0-1 The Hag in the Well can be banished by wagering arms The Well Man’s one’s life and then solve her riddle for three nights in a Hook 2 0-1 row. Alternatively blessing the water in the well by lowering the priest down to the water scares her away. Claws of the Hag 1 0 Examples of Conflicts • Near dalarne, Sweden, is an abandoned village. The neighbors believe all the residents have MAGICAL POWERS emigrated to America, but the truth is that a very • Enchant hungry Troll in the Well has eaten them all – and • Curse now it waits for travelers to stay the night. The • Trollcraft troll has connected all the wells in the village, and • The Man in the Well’s strength grwos as the fear of it begins by eating the horses of the travelers. him grows. Anyone failing a fear test he will gain +2 • Skånevik, Norway, is being plagued by a hook man, bonus against. -

Number Symbolism in Old Norse Literature

Háskóli Íslands Hugvísindasvið Medieval Icelandic Studies Number Symbolism in Old Norse Literature A Brief Study Ritgerð til MA-prófs í íslenskum miðaldafræðum Li Tang Kt.: 270988-5049 Leiðbeinandi: Torfi H. Tulinius September 2015 Acknowledgements I would like to thank firstly my supervisor, Torfi H. Tulinius for his confidence and counsels which have greatly encouraged my writing of this paper. Because of this confidence, I have been able to explore a domain almost unstudied which attracts me the most. Thanks to his counsels (such as his advice on the “Blóð-Egill” Episode in Knýtlinga saga and the reading of important references), my work has been able to find its way through the different numbers. My thanks also go to Haraldur Bernharðsson whose courses on Old Icelandic have been helpful to the translations in this paper and have become an unforgettable memory for me. I‟m indebted to Moritz as well for our interesting discussion about the translation of some paragraphs, and to Capucine and Luis for their meticulous reading. Any fault, however, is my own. Abstract It is generally agreed that some numbers such as three and nine which appear frequently in the two Eddas hold special significances in Norse mythology. Furthermore, numbers appearing in sagas not only denote factual quantity, but also stand for specific symbolic meanings. This tradition of number symbolism could be traced to Pythagorean thought and to St. Augustine‟s writings. But the result in Old Norse literature is its own system influenced both by Nordic beliefs and Christianity. This double influence complicates the intertextuality in the light of which the symbolic meanings of numbers should be interpreted. -

'Goblinlike, Fantastic: Little People and Deep Time at the Fin De Siècle

ORBIT-OnlineRepository ofBirkbeckInstitutionalTheses Enabling Open Access to Birkbeck’s Research Degree output ’Goblinlike, fantastic: little people and deep time at the fin de siècle https://eprints.bbk.ac.uk/id/eprint/40443/ Version: Full Version Citation: Fergus, Emily (2019) ’Goblinlike, fantastic: little people and deep time at the fin de siècle. [Thesis] (Unpublished) c 2020 The Author(s) All material available through ORBIT is protected by intellectual property law, including copy- right law. Any use made of the contents should comply with the relevant law. Deposit Guide Contact: email ‘Goblinlike, Fantastic’: Little People and Deep Time at the Fin De Siècle Emily Fergus Submitted for MPhil Degree 2019 Birkbeck, University of London 2 I, Emily Fergus, confirm that all the work contained within this thesis is entirely my own. ___________________________________________________ 3 Abstract This thesis offers a new reading of how little people were presented in both fiction and non-fiction in the latter half of the nineteenth century. After the ‘discovery’ of African pygmies in the 1860s, little people became a powerful way of imaginatively connecting to an inconceivably distant past, and the place of humans within it. Little people in fin de siècle narratives have been commonly interpreted as atavistic, stunted warnings of biological reversion. I suggest that there are other readings available: by deploying two nineteenth-century anthropological theories – E. B. Tylor’s doctrine of ‘survivals’, and euhemerism, a model proposing that the mythology surrounding fairies was based on the existence of real ‘little people’ – they can also be read as positive symbols of the tenacity of the human spirit, and as offering access to a sacred, spiritual, or magic, world. -

Trolls, Elves and Fairies Coloring Book Ebook

TROLLS, ELVES AND FAIRIES COLORING BOOK PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Jan Sovak | 32 pages | 24 Oct 2002 | Dover Publications Inc. | 9780486423821 | English | New York, United States Trolls, Elves and Fairies Coloring Book PDF Book Chibi Doodle Whimsy Characters coloring book Volume 2Experience creative relaxation and fun with coloring! Average Rating: 2. It is typically described as being the offspring of a fairy , troll , elf or other legendary creature that has been secretly left in the place Thank you! Showing Reviewed by lizave lizave. Description A wonderland of wee folk, this imaginative coloring book is populated by gremlins, pixies, giants, and other fantasy characters. Write a review See all reviews Write a review. Paperback , 32 pages. The spell was placed on imagery that balances the two factions, and restores magic to Terraflippia. Want to Read Currently Reading Read. Email address. Be the first to ask a question about Trolls, Elves and Fairies. This is another beautiful hand drawn coloring book from Ena Beleno. This exciting new series includes tons of whimsical illustrations that are designed to spark creativity in growing young minds and to provide hours of fun at the same time! You know the saying: There's no time like the present Return to Book Page. There are traditional " little people " from European folklore : elves , gnomes , goblins , brownies , trolls and leprechauns. Lists with This Book. From the manufacturer No information loaded. This book is not yet featured on Listopia. All Languages. Same Day Delivery. Your feedback helps us make Walmart shopping better for millions of customers. Escape the Present with These 24 Historical Romances. -

La Revista De Taos and the Taps Cresset, 04-15-1905 Jose ́ Montaner

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Revista de Taos, 1905-1922 New Mexico Historical Newspapers 4-15-1905 La Revista de Taos and the Taps Cresset, 04-15-1905 Jose ́ Montaner Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/revista_taos_news Recommended Citation Montaner, Jose.́ "La Revista de Taos and the Taps Cresset, 04-15-1905." (1905). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/ revista_taos_news/607 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the New Mexico Historical Newspapers at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Revista de Taos, 1905-1922 by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AÑO IX (I TAOS, N EVO MÉXICO, $ AHA DO 13 DE ABKÍL DE 100- NO 15 vnV" r Organo Oficial tí 1 üíiipül Organ ilk H' - sai ti i i il Of f Condado deTao--- . r.-- í m v i Taos ÍNüjofy. Mb 8 14 M i' J 1 U AND TLTU TAOS CRESSET, ENGLISIH AND SPANISH. Periódico Liberal e Independiente, Del Pueblo, Para el Pueblo, y por . el Pueblo. Homero, 200. (Id .iiicstead entry No. 5617 ) " (Homestead entry No. 5672.) llamón EL PROFESOR La Muerte de Jesús. Martínez, Precinto no. 4, NOTICE FOR FUBLtf ION. NOTICE FOR PUBLICATION. fiadores Alex Adaniscn, A. Clothier y Donaciano Department rf the lnlerior, Department of the Interior, Cordova, 200 pesos. Land Offie at Santa Fe, N. M. Land Office at Santa Fe, N. M este reflnchlo'grnpo condenado por lesiones determvna-- ' Pedro A. Apartede Tafoya, Prec. no. -

The World of Paladium: a Players Guide

The World of Palladium: Players guide. The world of Paladium: A players guide. This guide and all of it's content is made according to the PALLADIUM BOOKS® INTERNET POLICY which can be found at http://www.palladiumbooks.com/policies.html. Palladium Fantasy RPG® is a registered trademark owned and licensed by Kevin Siembieda and Palladium Books, Inc © 1983, 1987, 1988, 1990 Kevin Siembieda; © 1995 Palladium Books, All rights reserved world wide. No part of this work may be reproduced in part or whole, in any form or by any means, without permission from the publisher. All incidents, situations, institutions, governments and people are fictional and any similarity to characters or persons living or dead is strictly coincidental." The staff of The World of Palladium can in no way be held responsible for anything in this guide, nor anything that happens at The World of Palladium server. Page 1 of 92 The World of Palladium: Players guide. Table of Contents The Server Rules:................................................................................................................................. 5 Starting tips:........................................................................................................................................11 The haks needed:................................................................................................................................ 12 Class Rules:....................................................................................................................................... -

Day of the Dead Traditions in Rural Mexican Villages

IN RURAL MEXICAN VILLAGES by Ann Murdy , writer and photographer ay of the Dead, or Día de los Muertos as it is known in México, is a celebration of life. It is a time we honor and celebrate the lives of those who are no longer with us by constructing home altars, or ofrendas, in their memory and visiting their graves. An altar brings a Dloved one back to life, and relatives place on it all the things the person once enjoyed eating or drinking. Additionally, ofrendas include mementos, photos of the relative, and a glass of water and bread. The altars are adorned with marigold flowers which represent the fragility of life. A pathway of vibrant marigold petals is sprinkled from the outside of the home to the foot of the altar. This pathway, adorned with lit candles, guides the souls back to the home. Sweet- smelling copal, an incense-like resin, is burned to aid in communication with the spirits. The Spanish friars brought All Saints’ Day (November 1) and All Souls’ Day (November 2) to México in the sixteenth century. In order to convert the indigenous people to Christianity, the friars allowed the people of México to continue their death rituals in November of each year. The earliest festival was the Aztec Festival of the Little Dead, which took place in Tlaxochimaco, the ninth month of their calendar, July 24–August 12. This festival honored children who had died. The second festival, the Great Festival of the Dead, took place during Huey Miccailhuitontli, the tenth month, August 13–September 1. -

A History of Halloween

A HISTORY OF HALLOWEEN Its pagan origin, sancti cation by Catholicism and return to paganism in modern times. The story of Halloween is very old, going back to the days of the Druids1 in England, where in fact, most of the secular customs that are now performed during Halloween were rst practiced. The Druids practiced many superstitious customs depending on their beliefs. They had two big feast days and one of these was their New Year’s Eve which was celebrated around the 31st of October. On this day they believed that all those who had died during the past year would rise from their graves and come to spend a last evening by the hearth where they had spent their days of the past. The Druids believed that at midnight all these souls would walk out of the town to be taken by the Lord of Death to the afterlife from where the souls would be able to tranmigrate.2 They also feared that if these souls were able to recognize them, that they would drag them down into the afterlife with them. The townspeople therefore wore costumes so as not to be recognizable. They wore these costumes as they e s c o r t e d the souls of the dead out to meet the Lord of Death. It is easy to see how the custom of wearing costumes (i.e., of demons, witches, etc.) on Halloween has never had anything to do with those customs of Christianity! When Catholicism came to England and Ireland, it encountered this very popular pagan custom. -

This Newspaper Was Created by the Students of the 5Th, 6Th, 7Th, 8Th and 9Th Forms and Their English Teachers

This newspaper was created by the Students of the 5th, 6th, 7th, 8th and 9th forms and their English teachers. We hope you get really scared when you read it! 5th A and B students 5th A and B students Hi! My name is Mike and I’m going to show you the routine of my favour- ite day: Halloween. First, I get up at 10:30am. Then I eat a huge bowl with crunchy eyes with milk for breakfast. That’s so good! After that, I give some chocolate to the children on my door. At 1:00 o’clock I have lunch. On a special day like this I usually eat brain with some blood above. After lunch, I watch horror movies and prepare the Halloween decoration for the night! In the evening, at 8:00 pm, I have dinner and I eat bones and drink blood again. At 9:30 PM I go out to scare people. After getting everyone scared, I come back home, normally at midnight, and watch kids with their little Hallow- een costumes. Finally, at 1:15 AM I go to sleep. This is my Halloween routine! I love this day so much! Halloween jokes and riddles What does a Panda ghost eat? Bam-Boo! How do vampire get around on Halloween? On blood vessels. Where does a ghost go on vacation? Hali-Boo. What kind of music do mummies like listening to on Halloween? Wrap music. Why was the ghost crying? He wanted his mummy. Eat, drink and be scary! What’s the skeletons favourite instrument? A tron-bone.