William Young

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Central Division

THE FOLLOWING IS THE PROVISIONAL LIST OF POLLING VENUES AS AT 3IST DECEMBER 2017 CENTRAL DIVISION The following is a Provisional List of Polling Venues released by the Fijian Elections Office FEO[ ] for your information. Members of the public are advised to log on to pvl.feo.org.fj to search for their polling venues by district, area and division. DIVISION: CENTRAL AREA: VUNIDAWA PRE POLL VENUES -AREA VUNIDAWA Voter No Venue Name Venue Address Count Botenaulu Village, Muaira, 1 Botenaulu Community Hall 78 Naitasiri Delailasakau Community Delailasakau Village, Nawaidi- 2 107 Hall na, Naitasiri Korovou Community Hall Korovou Village, Noimalu , 3 147 Naitasiri Naitasiri Laselevu Village, Nagonenicolo 4 Laselevu Community Hall 174 , Naitasiri Lomai Community Hall Lomai Village, Nawaidina, 5 172 Waidina Naitasiri 6 Lutu Village Hall Wainimala Lutu Village, Muaira, Naitasiri 123 Matainasau Village Commu- Matainasau Village, Muaira , 7 133 nity Hall Naitasiri Matawailevu Community Matawailevu Village, Noimalu , 8 74 Hall Naitasiri Naitasiri Nabukaluka Village, Nawaidina ELECTION DAY VENUES -AREA VUNIDAWA 9 Nabukaluka Community Hall 371 , Naitasiri Nadakuni Village, Nawaidina , Voter 10 Nadakuni Community Hall 209 No Venue Name Venue Address Naitasiri Count Nadovu Village, Muaira , Nai- Bureni Settlement, Waibau , 11 Nadovu Community Hall 160 1 Bureni Community Hall 83 tasiri Naitasiri Naitauvoli Village, Nadara- Delaitoga Village, Matailobau , 12 Naitauvoli Community Hall 95 2 Delaitoga Community Hall 70 vakawalu , Naitasiri Naitasiri Nakida -

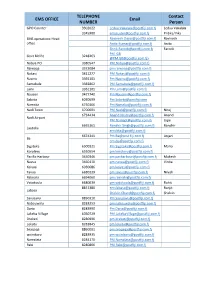

EMS Operations Centre

TELEPHONE Contact EMS OFFICE Email NUMBER Person GPO Counter 3302022 [email protected] Ledua Vakalala 3345900 [email protected] Pritika/Vika EMS operations-Head [email protected] Ravinesh office [email protected] Anita [email protected] Farook PM GB Govt Bld Po 3218263 @[email protected]> Nabua PO 3380547 [email protected] Raiwaqa 3373084 [email protected] Nakasi 3411277 [email protected] Nasinu 3392101 [email protected] Samabula 3382862 [email protected] Lami 3361101 [email protected] Nausori 3477740 [email protected] Sabeto 6030699 [email protected] Namaka 6750166 [email protected] Nadi Town 6700001 [email protected] Niraj 6724434 [email protected] Anand Nadi Airport [email protected] Jope 6665161 [email protected] Randhir Lautoka [email protected] 6674341 [email protected] Anjani Ba [email protected] Sigatoka 6500321 [email protected] Maria Korolevu 6530554 [email protected] Pacific Harbour 3450346 [email protected] Mukesh Navua 3460110 [email protected] Vinita Keiyasi 6030686 [email protected] Tavua 6680239 [email protected] Nilesh Rakiraki 6694060 [email protected] Vatukoula 6680639 [email protected] Rohit 8812380 [email protected] Ranjit Labasa [email protected] Shalvin Savusavu 8850310 [email protected] Nabouwalu 8283253 [email protected] -

Setting Priorities for Marine Conservation in the Fiji Islands Marine Ecoregion Contents

Setting Priorities for Marine Conservation in the Fiji Islands Marine Ecoregion Contents Acknowledgements 1 Minister of Fisheries Opening Speech 2 Acronyms and Abbreviations 4 Executive Summary 5 1.0 Introduction 7 2.0 Background 9 2.1 The Fiji Islands Marine Ecoregion 9 2.2 The biological diversity of the Fiji Islands Marine Ecoregion 11 3.0 Objectives of the FIME Biodiversity Visioning Workshop 13 3.1 Overall biodiversity conservation goals 13 3.2 Specifi c goals of the FIME biodiversity visioning workshop 13 4.0 Methodology 14 4.1 Setting taxonomic priorities 14 4.2 Setting overall biodiversity priorities 14 4.3 Understanding the Conservation Context 16 4.4 Drafting a Conservation Vision 16 5.0 Results 17 5.1 Taxonomic Priorities 17 5.1.1 Coastal terrestrial vegetation and small offshore islands 17 5.1.2 Coral reefs and associated fauna 24 5.1.3 Coral reef fi sh 28 5.1.4 Inshore ecosystems 36 5.1.5 Open ocean and pelagic ecosystems 38 5.1.6 Species of special concern 40 5.1.7 Community knowledge about habitats and species 41 5.2 Priority Conservation Areas 47 5.3 Agreeing a vision statement for FIME 57 6.0 Conclusions and recommendations 58 6.1 Information gaps to assessing marine biodiversity 58 6.2 Collective recommendations of the workshop participants 59 6.3 Towards an Ecoregional Action Plan 60 7.0 References 62 8.0 Appendices 67 Annex 1: List of participants 67 Annex 2: Preliminary list of marine species found in Fiji. 71 Annex 3 : Workshop Photos 74 List of Figures: Figure 1 The Ecoregion Conservation Proccess 8 Figure 2 Approximate -

Ministry of Lands and Mineral Resources

i List of Tables & Figures LIST OF FIGURES Figure 1 Mineral Investigation Project at Rakiraki ........................................ 47 Figure 2 Mineral Investigation Project at Ovalau ......................................... 47 LIST OF TABLES Table 1 Land Use Division Achievements 2013 .............................................. 45 Table 2 Land Management Division Achievements 2013 ............................. 46 Table 3 Land Valuation Division Achievement .............................................. 46 Table 4 List of Community Boreholes drilled & status ................................. 48 Table 5 Geotech drill holes and locations ..................................................... 48 Table 6 Number of project assessments conducted ................................... 49 Table 7 Production of Gold (Au) and Silver (Ag) for 2012/2013 .................... 49 Table 8 Production of Bauxite for 2012/2013 ................................................ 49 Table 9 Revenue collected for the year 2013 (Mines Division) .................... 50 Table 10 Overseas Training Attended ............................................................ 51 Table 11 Local Courses Attended ................................................................... 53 ii Letter to the Honourable Prime Minister & 1 Minister for Lands & Mineral Resources 1 2 Permanent Secretary’s Overview ‘ Through basic steps, and team efforts, the ideals of working smart are taking root in the ministry. ’ PSLMR Tevita Boseiwaqa With the vision to pursue growth through smart -

Domestic Air Services Domestic Airstrips and Airports Are Located In

Domestic Air Services Domestic airstrips and airports are located in Nadi, Nausori, Mana Island, Labasa, Savusavu, Taveuni, Cicia, Vanua Balavu, Kadavu, Lakeba and Moala. Most resorts have their own helicopter landing pads and can also be accessed by seaplanes. OPERATION OF LOCAL AIRLINES Passenger per Million Kilometers Performed 3,000 45 40 2,500 35 2,000 30 25 1,500 International Flights 20 1,000 15 Domestic Flights 10 500 5 0 0 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 Revenue Tonne – Million KM Performed 400,000 4000 3500 300,000 3000 2500 200,000 2000 International Flights 1500 100,000 1000 Domestic Flights 500 0 0 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 Principal Operators Pacific Island Air 2 x 8 passenger Britton Norman Islander Twin Engine Aircraft 1 x 6 passenger Aero Commander 500B Shrike Twin Engine Aircraft Pacific Island Seaplanes 1 x 7 place Canadian Dehavilland 1 x 10 place Single Otter Turtle Airways A fleet of seaplanes departing from New Town Beach or Denarau, As well as joyflights, it provides transfer services to the Mamanucas, Yasawas, the Fijian Resort (on the Queens Road), Pacific Harbour, Suva, Toberua Island Resort and other islands as required. Turtle Airways also charters a five-seater Cessna and a seven-seater de Havilland Canadian Beaver. Northern Air Fleet of six planes that connects the whole of Fiji to the Northern Division. 1 x Britten Norman Islander 1 x Britten Norman Trilander BN2 4 x Embraer Banderaintes Island Hoppers Helicopters Fleet comprises of 14 aircraft which are configured for utility operations. -

Guide to Fiji – Living & Investing

FIJI AT A GLANCE SIZE : 332 islands (approx.one - third are inhabited) TOTAL AREA : 18,333 sq.km. (Viti Levu - 10,429sq.km Vanua Levu - 5,556sq.km) LAND : 82.9% Native Land, 8.41% State Land 8.06% Freehold Land, 0.24% Rotuman Community Owned CLIMATE : Southsea Maritime Climate SEASONS : May - October (cooler months) November - April (dry months) CAPITAL : Suva INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT : Nadi, Nausori POPULATION : 772,655 (Census August 25, 1996) This included 394,999 Fijians(51.1%), 336,579 Indians (43.6%) and 41,077 (5.3%) others. LABOUR FORCE : 301,500 ( as at December 1996) LANGUAGES : English, Fijian, Hindi and Rotuman CURRENCY : Fiji Dollar TIME : 12 hours ahead of Greenwich Mean Time. FIJI TODAY 2004 / 2005 Ministry of Information, Communications and Media Relations CONTENTS 1 GEOGRAPHY 22 Diplomatic Mission Population 2 Climate 23 ECONOMY Flora/fauna 23 Overview 2004 3 Land Administration 24 Natural Resource Sector Native Land Trust Land Sugar Industry Mineral Resources 5 HISTORY/PEOPLE 25 Manufacturing Culture Transport, Storage & Communication 6 Great Council of Chiefs Tourism Europeans 26 Investment 7 20th Century Labour Market Citizenship 27 Inflation 8 Immigration Monetary Policy Religion Trade Race Relations Balance of Payments Language 28 Foreign Reserves Women Government’s 2004 Budget 9 Youths 29 Government’s Medium Term Strategies Investment Packages 11 GOVERNMENT, EXTERNAL Taxation RELATIONS AND CONSTITUTION 30 Indigenous Fijian Affirmative Action 12 Constitution 13 Parliament 31 TRADE AND INVESTMENT Cabinet 32 Increased -

4348 Fiji Planning Map 1008

177° 00’ 178° 00’ 178° 30’ 179° 00’ 179° 30’ 180° 00’ Cikobia 179° 00’ 178° 30’ Eastern Division Natovutovu 0 10 20 30 Km 16° 00’ Ahau Vetauua 16° 00’ Rotuma 0 25 50 75 100 125 150 175 200 km 16°00’ 12° 30’ 180°00’ Qele Levu Nambouono FIJI 0 25 50 75 100 mi 180°30’ 20 Km Tavewa Drua Drua 0 10 National capital 177°00’ Kia Vitina Nukubasaga Mali Wainingandru Towns and villages Sasa Coral reefs Nasea l Cobia e n Pacific Ocean n Airports and airfields Navidamu Labasa Nailou Rabi a ve y h 16° 30’ o a C Natua r B Yanuc Division boundaries d Yaqaga u a ld Nabiti ka o Macuata Ca ew Kioa g at g Provincial boundaries Votua N in Yakewa Kalou Naravuca Vunindongoloa Loa R p Naselesele Roads u o Nasau Wailevu Drekeniwai Laucala r Yasawairara Datum: WGS 84; Projection: Alber equal area G Bua Bua Savusavu Laucala Denimanu conic: standard meridan, 179°15’ east; standard a Teci Nakawakawa Wailagi Lala w Tamusua parallels, 16°45’ and 18°30’ south. a Yandua Nadivakarua s Ngathaavulu a Nacula Dama Data: VMap0 and Fiji Islands, FMS 16, Lands & Y Wainunu Vanua Levu Korovou CakaudroveTaveuni Survey Dept., Fiji 3rd Edition, 1998. Bay 17° 00’ Nabouwalu 17° 00’ Matayalevu Solevu Northern Division Navakawau Naitaba Ngunu Viwa Nanuku Passage Bligh Water Malima Nanuya Kese Lau Group Balavu Western Division V Nathamaki Kanacea Mualevu a Koro Yacata Wayalevu tu Vanua Balavu Cikobia-i-lau Waya Malake - Nasau N I- r O Tongan Passage Waya Lailai Vita Levu Rakiraki a Kade R Susui T Muna Vaileka C H Kuata Tavua h E Navadra a Makogai Vatu Vara R Sorokoba Ra n Lomaiviti Mago -

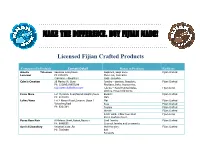

Make the Difference. Buy Fijian Made! ……………………………………………………….…

…….…………………………………………………....…. MAKE THE DIFFERENCE. BUY FIJIAN MADE! ……………………………………………………….…. Licensed Fijian Crafted Products Companies/Individuals Contact Detail Range of Products Emblems Amelia Yalosavu Sawarua Lokia,Rewa Saqamoli, Saqa Vonu Fijian Crafted Lesumai Ph:8332375 Mua i rua, Ramrama (Sainiana – daughter) Saqa -gusudua Cabe’s Creation 20 Marino St, Suva Jewelry - earrings, Bracelets, Fijian Crafted Ph: 3318953/9955299 Necklace, Belts, Accessories. [email protected] Fabrics – Hand Painted Sulus, Fijian Sewn Clothes, Household Items Finau Mara Lot 15,Salato Road,Namdi Heights,Suva Baskets Fijian Crafted Ph: 9232830 Mats Lolive Vana Lot 2 Navani Road,Suvavou Stage 1 Mat Fijian Crafted Votualevu,Nadi Kuta Fijian Crafted Ph: 9267384 Topiary Fijian Crafted Wreath Fijian Crafted Patch work- Pillow Case Bed Fijian Sewn Sheet Cushion Cover. Paras Ram Nair 6 Matana Street,Nakasi,Nausori Shell Jewelry Fijian Crafted Ph: 9049555 Coconut Jewelry and ornaments Seniloli Jewellery Veiseisei,Vuda ,Ba Wall Hanging Fijian Crafted Ph: 7103989 Belt Pendants Makrava Luise Lot 4,Korovuba Street,Nakasi Hand Bags Fijian Crafted Ph: 3411410/7850809 Fans [email protected] Flowers Selai Buasala Karova Settlement,Laucala bay Masi Fijian Crafted Ph:9213561 Senijiuri Tagi c/-Box 882, Nausori Iri-Buli Fijian Crafted Vai’ala Teruka Veisari Baskets, Place Mats Fijian Crafted Ph:9262668/3391058 Laundary Baskets Trays and Fruit baskets Jonaji Cama Vishnu Deo Road, Nakasi Carving – War clubs, Tanoa, Fijian Crafted PH: 8699986 Oil dish, Fruit Bowl Unik -

Lami Town Cities and Climate Change Initiative Vulnerability and Adaptation Assessment

CITIES AND CLIMATE CHANGE INITIATIVE: Lami Town Climate Change Vulnerability and Adaptation Assessment 2011 Lami Town Climate Change Vulnerability and Adaptation Assessment Document history and status Revision Date issued Reviewed by Approved by Date approved Revision type Draft 11th July 2011 J Hughes J Hughes 12th Aug 2011 Internal Review Final Draft 11th Sept 2011 J Hughes J Hughes 26th Sept 2011 Internal Review 26th Sept 2011 S Mecartney S Mecartney 9th Oct 2011 Client Review UNH UNH - Suva 26th Sept 2011 P Ieli - Lami P Ieli - Lami 20th Oct 2011 CCCI Partner Review Town Council Town Council 26th Sept 2011 C Radford – C Radford – 23rd Oct 2011 Client Review UNH Fukuoka UNH Fukuoka 26th Sept 2011 B Bathe – UNH B Bathe – UNH 24th Oct 2011 Client Review Nairobi Nairobi Final 9th Nov 2011 J Hughes J Hughes 17th Nov 2011 Final Internal Review 20th Nov 2011 S Mecartney S Mecartney UNH UNH - Suva 20th Nov 2011 P Ieli - Lami P Ieli - Lami Town Council Town Council 20th Nov 2011 C Radford – C Radford – UNH Fukuoka UNH Fukuoka Distribution of copies Revision Copy no Quantity Issued to Final Draft Soft Copy 1 Client (for review) 1 Partner (for review) Printed: 27 January 2012 Last saved: 27 January 2012 09:53 AM C:\Users\jhughes\Desktop\V&A\Lami Town VA Assessment_Report_Final Issue to UNH File name: 20Nov2011.docx Project Manager Jacqueline Hughes Author SCOPE Pacific Ltd Name of organisation: UN-Habitat Name of project: Cities & Climate Change Initiatives Name of document: Lami Town Vulnerability & Adaptation Assessment Document version: Final 2 Lami Town Climate Change Vulnerability and Adaptation Assessment Table of Contents 1. -

(OCOF) No. 163 Country: Fiji TABLE 1: Monthly Rainfall

Pacific Islands - Online Climate Outlook Forum (OCOF) No. 163 Country: Fiji TABLE 1: Monthly Rainfall Mar-2021 Jan-2021 Feb-2021 Station (include data period) Total 33%tile 67%tile Median (mm) Rank Total Total Rainfall (mm) (mm) (mm) Western Division Penang Mill (1910-2021) 1008.0 471.7 392.3 285.8 456.6 381.3 65/112 Lautoka Mill (1900-2021) 676.3 305.2 308.3 229.3 418.2 301.8 66/121 Nadi Airport (1942-2021) 538.8 332.8 308.9 249.8 415.6 321.2 38/78 Central Division Laucala Bay (Suva) (1942-2021) 578.4 143.9 545.8 298.0 429.0 343.3 70/80 Nausori Airport (1957-2021) 553.7 211.7 466.9 312.8 439.9 362.6 52/65 Tokotoko (Navua) (1945-2021) 432.5 M 322.6 314.5 440.3 378.8 27/77 Eastern Division Lakeba (1950-2021) 487.7 346.2 245.2 212.6 330.8 260.2 33/71 Vunisea (Kadavu) (1931-2021) 446.9 177.8 135.6 229.4 309.1 285.3 10/85 Ono-i-Lau (1943-2021) 295.4 97.8 273.3 163.1 295.7 226.6 48/74 Northern Division Labasa Airport (1946-2021) M 346.2 259.5 264.5 430.6 329.4 21/65 Savusavu Airfield (1956-2021) M M M 179.9 272.9 228.2 M Udu Point (1946-2021) 582.4 320.2 344.7 255.7 363.7 300.7 45/74 Rotuma (1912-2021) 671.9 559.6 157.0 275.9 409.3 326.5 7/108 TABLE 2: Three-month Rainfall for January to March 2021 SCOPIC forecast probabilities Verification: Three-month Total 33%tile 67%tile Median Consistent, Station Rank based on NINO3.4 October-November 2020 Near-consistent, Inconsistent? Rainfall (mm) B-N N A-N LEPS Western Division Penang Mill (1910-2021) 1872.0 Above normal 1035.8 1250.0 1124.2 106/112 7 34 59 27 Consistent Lautoka Mill (1900-2021) 1289.8 -

Fiji Islands Weather Summary September 2003 Rainfall Outlook

Fiji Islands Weather Summary Volume 3: Issue: 9 September 2003 September 2003 Rainfall Outlook till December 2003 FIJI METEOROLOGICAL SERVICE In Brief Inside this issue: Rainfall in September was well below average the El Niño on Fiji’s rainfall which can (<40% of normal) across the country except continue for a number of months after the for Rotuma (52%). Greatest suppression was El Niño has phased out. In Brief and Weather 1 in the Western Division, Northern Vanua Patterns Levu and parts of the Eastern Division where Night-time air temperatures were generally rainfall received was less than 10% of normal. below average and Day-time above average Rainfall in the last three 2 months across the country. Relative Humidity was With rainfall being well below average in the generally below average. Temp. and RR Graphs for 3 last month, Drought conditions have been en- Suva, Nadi & Labasa hanced and the area affected has expanded Total sunshine hours ranged from average from the previous month. For six of the nine- to above average for the month of Septem- Other Climatic variables 4 teen stations that reported in time for this ber. summary, rainfall in the last three months was within the lowest ten-percent and in a couple Rainfall in the next three months is ex- SOI & Prospects for Up- 5 coming Three Months of cases within the lowest five-percent on re- pected to be vary around average. The cord. amount of rainfall received in the coming Figures and Preliminary 6 months should increase as we progress into Climatological Summary Ocean and Atmosphere conditions are cur- the Wet season especially with the official rently ‘Neutral’ and have been ‘Neutral’ for Tropical Cyclone Season beginning in No- FMS Rainfall forecast 7 some time. -

Status of Coral Reefs in the Fiji Islands 2007

COMPONENT 2A - Project 2A2 Knowledge, monitoring, management and beneficial use of coral reef ecosystems January 2009 REEF MONITORING SOUTH-WEST PACIFIC STATUS OF CORAL REEFS REPORT 2007 Edited by Cherrie WHIPPY-MORRIS Institute of Marine Resources With the support of: Photo: E. CLUA The CRISP programme is implemented as part of the Regional Environment Programme for a contribution to conservation and sustainable development of coral T (CRISP), sponsored by France and prepared by the French Development Agency (AFD) as part of an inter-ministerial project from 2002 onwards, aims to develop a vi- sion for the future of these unique eco-systems and the communities that depend on them and to introduce strategies and projects to conserve their biodiversity, while developing the economic and environmental services that they provide both locally and globally. Also, it is designed as a factor for integration between developed coun- - land developing countries. The CRISP Programme comprises three major components, which are: Component 1A: Integrated Coastal Management and watershed management - 1A1: Marine biodiversity conservation planning - 1A2: Marine Protected Areas - 1A3: Institutional strengthening and networking - 1A4: Integrated coastal reef zone and watershed management CRISP Coordinating Unit (CCU) Component 2: Development of Coral Ecosystems Programme manager : Eric CLUA - 2A: Knowledge, monitoring and management of coral reef ecosytems SPC - PoBox D5 - 2B: Reef rehabilitation 98848 Noumea Cedex - 2C: Development of active marine substances