Spark Joy? Compulsory Happiness and the Feminist Politics of Decluttering

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Television Academy Awards

2019 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Comedy Series A.P. Bio Abby's After Life American Housewife American Vandal Arrested Development Atypical Ballers Barry Better Things The Big Bang Theory The Bisexual Black Monday black-ish Bless This Mess Boomerang Broad City Brockmire Brooklyn Nine-Nine Camping Casual Catastrophe Champaign ILL Cobra Kai The Conners The Cool Kids Corporate Crashing Crazy Ex-Girlfriend Dead To Me Detroiters Easy Fam Fleabag Forever Fresh Off The Boat Friends From College Future Man Get Shorty GLOW The Goldbergs The Good Place Grace And Frankie grown-ish The Guest Book Happy! High Maintenance Huge In France I’m Sorry Insatiable Insecure It's Always Sunny in Philadelphia Jane The Virgin Kidding The Kids Are Alright The Kominsky Method Last Man Standing The Last O.G. Life In Pieces Loudermilk Lunatics Man With A Plan The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel Modern Family Mom Mr Inbetween Murphy Brown The Neighborhood No Activity Now Apocalypse On My Block One Day At A Time The Other Two PEN15 Queen America Ramy The Ranch Rel Russian Doll Sally4Ever Santa Clarita Diet Schitt's Creek Schooled Shameless She's Gotta Have It Shrill Sideswiped Single Parents SMILF Speechless Splitting Up Together Stan Against Evil Superstore Tacoma FD The Tick Trial & Error Turn Up Charlie Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt Veep Vida Wayne Weird City What We Do in the Shadows Will & Grace You Me Her You're the Worst Young Sheldon Younger End of Category Outstanding Drama Series The Affair All American American Gods American Horror Story: Apocalypse American Soul Arrow Berlin Station Better Call Saul Billions Black Lightning Black Summer The Blacklist Blindspot Blue Bloods Bodyguard The Bold Type Bosch Bull Chambers Charmed The Chi Chicago Fire Chicago Med Chicago P.D. -

Decluttering Doyenne MARIE KONDO Is Poised To

1. FAST COMPANY FAST b y ELIZABETH SEGRAN may/june 2020 may/june photographs by by photographs 2. CARA ROBBINS 3. 4. Decluttering doyenne MARIE KONDO is poised to build the next lifestyle empire, but will it spark joy? P G. 42 She’s wearing a white bathrobe and standing next to a bouquet of tures any seriousness, making funny faces, constellation of stardom, alongside other goddesses of wellness and pink cherry blossoms. She has asked for soft instrumental music telling jokes, and putting everyone at ease. TWOFER domesticity such as Martha Stewart, Oprah Winfrey, and Gwyneth to be piped into the room. It appears to calm her on this February It’s partly his personality, but it’s also a stra- “We’re two people, Paltrow. By the end of 2019, she had established an e-commerce site, morning in Los Angeles as a dozen production workers mill about, tegic effort to relax his wife. Kondo has been but working as one,” a blog, and a newsletter. She had also increased the size of her con- capturing footage that will show Kondo’s 2.5 million Instagram fol- in the public eye since 2011, when she pub- Kawahara says of sultant network—people whom Kondo personally instructs in her lowers how to dry brush their faces. Kondo closes her eyes, takes a lished The Life-Changing, Pulsing Magic of himself and Kondo. decluttering method—to 40 countries. deep breath, and starts making small circular motions on her fore- Tidying Up in Japan, but she’s still happiest Now, Kondo is bringing her method to the workplace, backed by head. -

For Immediate Release First Night of 2019 Creative Arts

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE FIRST NIGHT OF 2019 CREATIVE ARTS EMMY® WINNERS ANNOUNCED (Los Angeles, Calif. – Sept. 14, 2019) The Television Academy tonight presented the first of its two 2019 Creative Arts Emmy® Awards ceremonies honoring outstanding artistic and technical achievement in television at the Microsoft Theater in Los Angeles. The ceremony, which kicked-off the 71st Emmys, awarded many talented artists and craftspeople in categories including reality, variety special, documentary, animated program and short form animation, choreography for variety or reality program, and interactive program. This year’s first Creative Arts Awards, executive produced by Bob Bain, featured presenters from television’s top shows including Will Arnett (BoJack Horseman), Marsha Stephanie Blake (When They See Us), Roy Choi and Jon Favreau (The Chef Show), Terry Crews (America’s Got Talent), Jeff Goldblum (The World According to Jeff Goldblum), Seth Green (Robot Chicken), Diane Guerrero (Orange Is the New Black), Derek Hough (World of Dance), Marie Kondo (Tidying Up With Marie Kondo), Nick Kroll (Big Mouth) and Wanda Sykes (Wanda Sykes: Not Normal). FXX will broadcast the awards on Saturday, Sept. 21 at 8:00 PM ET/PT. Press Contacts: Stephanie Goodell breakwhitelight (for the Television Academy) [email protected], (818) 462-1150 For more information please visit emmys.com. TELEVISION ACADEMY 71ST CREATIVE ARTS EMMY AWARDS – SATURDAY The awards, as tabulated by the independent accounting firm of Ernst & Young LLP, were distributed as follows: Program Individual Total Netflix 3 12 15 National Geographic 1 7 8 CNN 3 2 5 NBC 1 4 5 FOX 1 3 4 HBO 2 2 4 YouTube 1 3 4 CBS 1 2 3 VH1 0 3 3 ABC 1 0 1 Apple Music 1 0 1 CW 0 1 1 FX Networks 0 1 1 Oculus Store 1 0 1 Twitch 1 0 1 A complete list of all awards presented tonight is attached. -

Climate Change Exemplarity Edited by Kyrre

Culture Unbound: Journal of Current Cultural Research Thematic Sections: Climate Change Exemplarity Edited by Kyrre Kverndokk and Marit Ruge Bjærke Thrift, Dwelling and TV Edited by Aneta Podkalicka and Alexa Färber Volume 11, Issue 3–4 2019 Linköping University Electronic Press Culture Unbound: ISSN 2000-1525 (online) URL: http://www.cultureunbound.ep.liu.se/ © 2019 The Authors. Culture Unbound, Volume 11, Issue 3–4 2019 Thematic Section: Climate Change Exemplarity Introduction: Exemplifying Climate Change Kyrre Kverndokk and Marit Ruge Bjærke .......................................................................... 298 Risk Perception through Exemplarity: Hurricanes as Climate Change Examples and Counterexamples in Norwegian News Media Kyrre Kverndokk ................................................................................................................. 307 The Past as a Mirror: Deep Time Climate Change Exemplarity in the Anthropocene Henrik Svensen, Marit Ruge Bjærke and Kyrre Kverndokk .............................................. 330 History, Exemplarity and Improvements: 18th Century Ideas about Man-Made Climate Change Anne Eriksen ....................................................................................................................... 353 Touchstones for Sustainable Development: Indigenous Peoples and the Anthropology of Sustainability in Our Common Future John Ødemark ..................................................................................................................... 369 Making Invisible -

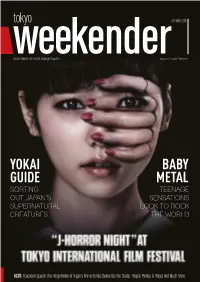

Yokai Guide Baby Metal

OCTOBER 2015 Japan’s number one English language magazine Image © 2015 “Gekijorei” Film Partners YOKAI BABY GUIDE METAL SORTING TEENAGE OUT JAPAN’S SENSATIONS SUPERNATURAL LOOK TO ROCK CREATURES THE WORLD ALSO: Education Special, the Hoop Nation of Nippon, Marie Kondo Cleans Out the Clutter, People, Parties, & Placeswww.tokyoweekender.com and Much MoreOCTOBER 2015 OCTOBER 2015 www.tokyoweekender.com OCTOBER 2015 CONTENTS 15 MASTERS OF J-HORROR The Tokyo International Film Festival brings plenty of screams to the screen © 2015 “Gekijorei” Film Partners 14 16 20 BABYMETAL YOKAI GUIDE EDUCATION SPECIAL Awww...These teenagers are on a rock- Don’t know your kappa from your kirin? Autumn is filled with new developments fueled musical rampage Turn to page 16, dear friends at Tokyo’s international schools 6 The Guide 13 Akita-Style Teppanyaki 34 Previews Our recommendations for hot fall looks, Get ready for some of Japan’s finest The back story of Peter Pan, Keanu takes plus a snack that’s worth a train ride ingredients, artfully prepared at Gomei revenge, and the Not-So-Fantastic Four 8 Gallery Guide 28 Marie Kondo 36 Agenda Edo period adult art, the College Women’s Reclaiming joy by getting rid of clutter? Shimokita Curry Festival, Tokyo Design Association of Japan Print Show, and more Sounds like a win-win Week, and other October happenings 10 Japan Hoops It Up 30 People, Parties, Places 38 Back in the Day Lace ‘em up and get fired up for the A very French soirée, a tasty evening for Looking back at a look ahead to the CWAJ coming season of NBA action Peru, and Bill back in the Studio 54 days Print Show, circa 1974 www.tokyoweekender.com OCTOBER 2015 THIS MONTH IN THE WEEKENDER and domestic for decades, and this year the Tokyo International Film Festival OCTOBER 2015 has decided to take a walk on the spooky side, celebrating the work of three masters of “J-Horror,” including Hideo Nakata, whose upcoming release “Ghost Theater” gets the cover this month. -

Japan Week 2019

Welcome to Japan Week 2019 Light Up Your World with Japan JAPAN WEEK 2019 Japan Week 2019 aims to give students and communities the opportunity to obtain a better understanding of Japa- nese culture and demonstrate the Uni- Light Up Your World with Japan versity's ongoing commitment to build- ing bridges between cultures and bring- April 3 (Wednesday) ing together people of different customs, April 1 (Monday) 2:00 p.m. - 3:10 p.m. Beck Room religions and ethnic backgrounds. Japan 3:30 p.m. - 4:30 p.m. Beck Room Week 2019 seeks to continue to promote Does this Spark Joy? Karuta: Traditional Card Game from Portugal Marie Kondo effect in Historical Perspective diversity and unity and hopes that par- ticipants will become leaders in a flour- Karuta is a card game that has been The Netflix show, Tidying Up with ishing dialogue between Japan and the popular with the Japanese since the 16th Marie Kondo, has become an overnight United States and will work towards century. Come get hands on experience sensation garnering media coverage building a more peaceful global commu- with this traditional game! Following a from news organizations like the New York Times, the Atlantic, and the nity. The goal of Japan Week 2019 is to short presentation on the history of Karu- ta, attendees will be invited to compete Guardian. This talk goes beyond the support an inclusive environment for hype to investigate the history behind students and community members of all with each other. Winners will be able to keep their Karuta cards. -

Events Held Ahead of 2020 Tokyo Olympic Games

"One Year to Go!" Events Held Ahead of 2020 Tokyo Olympic Games On July 24, Prime Minister Shinzo Abe attended the "One Year to Go" celebration and other events held in Tokyo in preparation for the Tokyo 2020 Olympic Games. Foreign Minister Kono's Overseas Travels: ASEAN- Related Meetings, Bangladesh, Myanmar and Pacific Islands Foreign Minister Taro Kono's latest overseas travels from July 29 to Aug. 9 have taken him to Bangladesh, Myanmar as well as Thailand for ASEAN-related meetings. He also visited Fiji, Palau, Micronesia and the Marshall Islands. 1 Introducing the Official Mascots of the Olympic and Paralympic Games Tokyo 2020: Miraitowa and Someity Meet Tokyo 2020 mascots Miraitowa and Someity on the second and fifth floors at JAPAN HOUSE Los Angeles, located at Hollywood & Highland. These official mascots will be available for selfies! Spring 2019 Decoration Conferred on Ms. Yasuko Sakamoto On May 21, 2019, the Government of Japan announced the recipients of its Spring 2019 Decorations and within this consulate general's jurisdiction, Ms. Yasuko Sakamoto received the Order of the Rising Sun, Silver Rays. The conferment ceremony for Ms. Sakamoto was held on July 12, at the Official Residence of the Consul General of Japan and was attended by approximately 45 guests, including Ms. Sakamoto's family and friends. Japan Night at Dodger Stadium! 2 With Consul General Chiba and rising tennis star Naomi Osaka starting the evening with Ceremonial First Pitches, Japan Night in Dodger Stadium saw a celebration of Japanese players and heritage; and in addition a wide variety of Japanese delicacies from the Trade Association of Confectionary Manufacturers (TACOM), providing samples to appreciative baseball fans in attendance. -

Joy at Work: Organizing Your Professional Life

Copyright Copyright © 2020 by KonMari Media Inc. and Scott Sonenshein English translation for Marie Kondo’s chapters by Cathy Hirano Cover design by Lauren Harms Cover art by Souun Takeda Cover copyright © 2020 by Hachette Book Group, Inc. Author photographs by KonMari Media, Inc. (Marie Kondo) and Chris Gillett Studios (Scott Sonenshein) Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture. The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the author’s intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact [email protected]. Thank you for your support of the author’s rights. Little, Brown Spark Hachette Book Group 1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104 littlebrownspark.com twitter.com/lbsparkbooks facebook.com/littlebrownspark Instagram.com/littlebrownspark First ebook edition: April 2020 Little, Brown Spark is an imprint of Little, Brown and Company, a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Little, Brown Spark name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher. The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591. The KonMari Method™ is a registered trademark -

Copy of New 71St-Nominations-Press-Brv1

71st Emmy® Awards Nominations Announcements July 16, 2019 (A complete list of nominations, supplemental facts and figures may be found at Emmys.com) Emmy Nominations Previous Wins 71st Emmy Nominee Program Network to date to date Nominations Total (across all categories) (across all categories) DRAMA SERIES Better Call Saul AMC 9 32 0 Bodyguard Netflix 2 2 NA Game Of Thrones HBO 32 161 47 Killing Eve BBC America 9 11 0 Ozark Netflix 9 14 0 Pose FX Networks 6 6 NA Succession HBO 5 5 NA This Is Us NBC 9 27 3 COMEDY SERIES Barry HBO 17 30 3 Fleabag Prime Video 11 11 NA The Good Place NBC 5 7 0 The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel Prime Video 20 34 8 Russian Doll Netflix 13 13 NA Schitt's Creek Pop TV 4 4 NA Veep HBO 9 68 17 LIMITED SERIES Chernobyl HBO 19 NA NA Escape At Dannemora Showtime 12 NA NA Fosse/Verdon FX Networks 17 NA NA Sharp Objects HBO 8 NA NA When They See Us Netflix 16 NA NA TELEVISION MOVIE Bandersnatch (Black Mirror) Netflix 2 NA NA Brexit HBO 1 NA NA Deadwood: The Movie HBO 8 NA NA King Lear Prime Video 1 NA NA My Dinner With Hervé HBO 1 NA NA LEAD ACTRESS IN A DRAMA SERIES Emilia Clarke Game Of Thrones HBO 1 4 0 Jodie Comer Killing Eve BBC America 1 1 NA Viola Davis How To Get Away With Murder ABC 1 5 1 Laura Linney Ozark Netflix 1 6 4 Mandy Moore This Is Us NBC 1 1 NA Sandra Oh* Killing Eve BBC America 2 8 0 Robin Wright House Of Cards Netflix 1 8 0 *Sandra Oh is also nominated for Guest Actress in a Comedy Series for Saturday Night Live LEAD ACTOR IN A DRAMA SERIES Jason Bateman* Ozark Netflix 2 6 0 Sterling K. -

The Way of Shinto Through Modern Japan

Háskóli Íslands. Hugvísindasvið. Japanskt mál og menning. The Way of Shinto Through Modern Japan. Ritgerð til B.A.-prófs í Japönsku máli og menningu Helena Konráðsdóttir Kt.: 300995-2419 Leiðbeinandi: Gunnella Þorgeirsdóttir Maí 2020 2 Abstract This essay examines the Japanese religious environment, how Shinto is connected to other religions as well as exploring how modern-day Japan is almost always influenced by Shinto one way or another. Firstly, the religious environment of Japan is explained as well as how Japan works as a syncretic religious system, as well as the difference between the terms of religion and belief and their definition. The origin of Shinto, as well as the different sects and the often referred to eight million gods, will be looked at and explained thoroughly. In the end Shinto as it appears in Miyazaki's movies, modern-day movies, video games, and Marie Kondo will be inspected thoroughly and described in more detail. The question presented in this essay is if Shinto should be classified as a belief or as a religion and also if modern influencers such as Marie Kondo have been influencing people by bringing Shinto into their lives with her tidying methods, without people being fully aware of it. 3 Table of Contents Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 4 1. The Japanese Religious Environment ............................................................................ 6 Religion vs Belief and a Religious Syncretistic -

Spark Joy? Compulsory Happiness and the Feminist Politics of Decluttering

Spark Joy? Compulsory Happiness and the Feminist Politics of Decluttering By Laurie Ouellette Abstract This essay analyzes the Marie Kondo brand as a set of neoliberal techniques for managing cultural anxieties around over-consumption, clutter and the family. Drawing from critical discussions of consumer culture and waste, as well as fe- minist scholarship on compulsory happiness and women’s labor in the home, it argues that Marie Kondo’s “joyful” approach to “tidying up” presents pared-down, curated consumption as a lifestyle choice that depends on women’s work, even as it promises to mitigate the stresses of daily life and facilitate greater well-being. Keywords: Marie Kondo, happiness, clutter, over-consumption, neoliberalism, post-feminism, housework, danshari Ouellette, Laurie: “Spark Joy? Compulsory Happiness and the Feminist Politics of Decluttering”, Culture Unbound, Volume 11, issue 3–4, 2019: 534–550. Published by Linköping University Electronic Press: http://www.cultureunbound.ep.liu.se Culture Unbound Journal of Current Cultural Research “The ideal of happiness has always taken material form in the house . .” --Simone de Beauvoir In the debut episode of the Netflix series Tidying Up With Marie Kondo, we meet the Friend family in their suburban, one-story bungalow on the outskirts of Los Angeles. Kevin is a sales manager for a restaurant supply company who works 50-60 hours per week and “then some on the weekends.” Rachel works part-time from home three days a week, while also caring for their two toddlers, Jaxon and Ryan, who is still nursing. The parents confess to fighting constantly about money and housework.