Climate Change and the South Australia Bushfire Threat

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Nature of Northern Australia

THE NATURE OF NORTHERN AUSTRALIA Natural values, ecological processes and future prospects 1 (Inside cover) Lotus Flowers, Blue Lagoon, Lakefield National Park, Cape York Peninsula. Photo by Kerry Trapnell 2 Northern Quoll. Photo by Lochman Transparencies 3 Sammy Walker, elder of Tirralintji, Kimberley. Photo by Sarah Legge 2 3 4 Recreational fisherman with 4 barramundi, Gulf Country. Photo by Larissa Cordner 5 Tourists in Zebidee Springs, Kimberley. Photo by Barry Traill 5 6 Dr Tommy George, Laura, 6 7 Cape York Peninsula. Photo by Kerry Trapnell 7 Cattle mustering, Mornington Station, Kimberley. Photo by Alex Dudley ii THE NATURE OF NORTHERN AUSTRALIA Natural values, ecological processes and future prospects AUTHORS John Woinarski, Brendan Mackey, Henry Nix & Barry Traill PROJECT COORDINATED BY Larelle McMillan & Barry Traill iii Published by ANU E Press Design by Oblong + Sons Pty Ltd The Australian National University 07 3254 2586 Canberra ACT 0200, Australia www.oblong.net.au Email: [email protected] Web: http://epress.anu.edu.au Printed by Printpoint using an environmentally Online version available at: http://epress. friendly waterless printing process, anu.edu.au/nature_na_citation.html eliminating greenhouse gas emissions and saving precious water supplies. National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry This book has been printed on ecoStar 300gsm and 9Lives 80 Silk 115gsm The nature of Northern Australia: paper using soy-based inks. it’s natural values, ecological processes and future prospects. EcoStar is an environmentally responsible 100% recycled paper made from 100% ISBN 9781921313301 (pbk.) post-consumer waste that is FSC (Forest ISBN 9781921313318 (online) Stewardship Council) CoC (Chain of Custody) certified and bleached chlorine free (PCF). -

Adelaide Coastal Waters Information Sheet No. 3

Adelaide Coastal Waters Information Sheet No. 3 Changes in urban environments Issued August 2009 EPA 769/09: This information sheet is part of a series of Fact Sheets on the Adelaide coastal waters and the findings of the Adelaide Coastal Waters Study (ACWS). Introduction Since European settlement in the 1830s, the Adelaide plains and Adelaide’s coastal environment have been subject to considerable change and pressure from a continually increasing population. In recent years there has been growing community concern about the effects of coastal and catchment development on the marine environment. Increases in stormwater flows and waste from wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) have also been of concern. Nutrients and other pollutants introduced to Adelaide’s nearshore waters from urban and rural runoff, WWTPs and some industrial sources have been found by the Adelaide Coastal Waters Study (ACWS) to have had a negative impact on Adelaide’s nearshore marine environment, including the loss of over 5,000 hectares of seagrass. Historical catchment changes When Adelaide was selected by Colonel William Light for South Australia’s state capital in 1836 there was a wide belt of coastal dunes and wide sandy beaches stretching to the north and south of Glenelg. From Seacliff to Outer Harbor there was a 30 km stretch of sand dunes broken only by the Patawalonga Creek at Glenelg. The Torrens River flowed into a series of swamps lying behind the coastal dunes and drained both north and south to the sea through the Patawalonga Creek and Port River system. The stretch of sand dunes comprised two or more parallel ridges each about 70 to 100 metres wide separated by narrow depressions or swales, consequently very little surface catchment runoff would have reached the coastline. -

Inbound Flights Into Adelaide Sydney to Adelaide

INBOUND FLIGHTS INTO ADELAIDE SYDNEY TO ADELAIDE DATE AIRLINE FLIGHT NUMBER DEPARTURE CITY DEPARTURE TIME ARRIVAL CITY ARRIVAL TIME 11 FEB 2018 JETSTAR JQ762 SYDNEY 0700 ADELAIDE 0835 11 FEB 2018 QANTAS QF1555 SYDNEY 0815 ADELAIDE 0955 11 FEB 2018 VIRGIN VA412 SYDNEY 0840 ADELAIDE 1020 11 FEB 2018 QANTAS QF741 SYDNEY 1045 ADELAIDE 1220 11 FEB 2018 QANTAS QF751 SYDNEY 1235 ADELAIDE 1410 11 FEB 2018 VIRGIN VA418 SYDNEY 1240 ADELAIDE 1420 11 FEB 2018 QANTAS QF759 SYDNEY 1355 ADELAIDE 1530 11 FEB 2018 QANTAS QF761 SYDNEY 1510 ADELAIDE 1645 11 FEB 2018 JETSTAR JQ764 SYDNEY 1530 ADELAIDE 1705 11 FEB 2018 VIRGIN VA428 SYDNEY 1610 ADELAIDE 1750 11 FEB 2018 QANTAS QF765 SYDNEY 1640 ADELAIDE 1815 11 FEB 2018 JETSTAR JQ768 SYDNEY 1725 ADELAIDE 1900 11 FEB 2018 QANTAS QF743 SYDNEY 1815 ADELAIDE 1950 11 FEB 2018 VIRGIN VA436 SYDNEY 1815 ADELAIDE 1955 11 FEB 2018 QANTAS QF783 SYDNEY 1955 ADELAIDE 2130 11 FEB 2018 JETSTAR JQ770 SYDNEY 2015 ADELAIDE 2150 11 FEB 2018 VIRGIN VA444 SYDNEY 2015 ADELAIDE 2155 11 FEB 2018 QANTAS QF785 SYDNEY 2035 ADELAIDE 2210 DATE AIRLINE FLIGHT NUMBER DEPARTURE CITY DEPARTURE TIME ARRIVAL CITY ARRIVAL TIME 12 FEB 2018 VIRGIN VA403 SYDNEY 0645 ADELAIDE 0825 12 FEB 2018 JETSTAR JQ762 SYDNEY 0700 ADELAIDE 0835 12 FEB 2018 QANTAS QF735 SYDNEY 0705 ADELAIDE 0840 12 FEB 2018 QANTAS QF739 SYDNEY 0820 ADELAIDE 0955 12 FEB 2018 VIRGIN VA412 SYDNEY 0840 ADELAIDE 1020 12 FEB 2018 JETSTAR JQ766 SYDNEY 1025 ADELAIDE 1200 12 FEB 2018 QANTAS QF741 SYDNEY 1045 ADELAIDE 1220 12 FEB 2018 QANTAS QF1557 SYDNEY 1130 ADELAIDE 1310 For any queries -

Causes of Bushfire Is Australia – a Response

Causes of bushfire is Australia – A response Colleen Bryant ©2020 Preamble A recent video shared on Facebook (https://www.facebook.com/watch/?v=837989649986602) is symbolic of a broader meme that has emerged in political, media, and social media circles regarding the role of arson in the current bushfire season. The above clip states that: “The popular narrative is that Australia’s fires are caused by climate change but the facts say otherwise”. It goes onto say that “since November 8, 2019 nearly 200 arsonists have been arrested for starting brush fires in Australia”. It then forwards “the arsonists were responsible for about 50% of the brushfires1”, before concluding that it is not climate change but arsonists that are responsible for Australia recent bushfires. The above statistic of 50% reportedly derives from an article published in “The Australian” newspaper (Ross & Reid, 2020) which states “Swinbourne University Professor James Ogloff said about 50 per cent of bushfire were lit by firebugs and impending seasons excited them.” The figure he quoted reportedly came from a study a fire statistics released 12 years ago, which would imply that that the professor was not speaking about the 2019‐20 season specifically. Articles similarly highlighting the role of arson have emerged in the Spectator (Chrenkoff, 2020) and Sydney Morning Herald (Rawsthorne, 2020). However, the above narrative is countered by a recent article published by Nguyen et al. (2020) for the ABC (Australian Broadcasting Commission), which examined the cause of many of the large fires on a state‐by‐state basis. Ultimately they concluded that deliberate fire‐setting did not play a significant role in the recent bushfires in New South Wales, Victoria, South Australia, or even Queensland. -

Environment Testing Visitor Information for Wollongong Office

Eurofins | Environment Testing Visitor Information for Wollongong Office Address - Eurofins | Environment Testing, Unit 16, 7 Investigator Drive, Unanderra, NSW 2526 Directions - Our Wollongong office is conveniently located in Unanderra’s Commercial precinct, at number Unit 16/7 Investigator Drive. - If approaching from M1 Princes Motorway/Princes Highway, take the Five Islands Rd exit towards Unanderra/Port Kembla. Turn left onto Five Islands Rd and at the roundabout, take the 2nd exit onto Glastonbury Ave. In about 900m turn right onto Berkley Rd. At the end of Berkley Rd turn left onto Investigator Dr. - Our office is roughly 200m on the left from the turn. = Eurofins | Environment Testing Eurofins Environment Testing Laboratories Wollongong Office Offices : Melbourne Unit 16, 7 Investigator Drive Adelaide Sydney Unanderra, NSW 2526 Darwin Brisbane Australia Newcastle Perth ABN: 50 005 085 521 Wollongong QS1081_R0 +61 2 9900 8492 Parking - There are 3 car spaces directly in front of the building, if the spaces are all occupied there is also on street parking out the front of the complex. General Information - The Wollongong office site includes a client services room available 24 hours / 7 days a week for clients to drop off samples and / or pick up bottles and stock. This facility available for Eurofins | Environment Testing clients, is accessed via a coded lock. For information on the code and how to utilize this access service, please contact Elvis Dsouza on 0447 584 487. - Standard office opening hours are between 8.30am to 5.00pm, Monday to Friday (excluding public holidays). We look forward to your visit. Eurofins | Environment Testing Management & Staff Eurofins Environment Testing Laboratories Wollongong Office Offices : Melbourne Unit 16, 7 Investigator Drive Adelaide Sydney Unanderra, NSW 2526 Darwin Brisbane Australia Newcastle Perth ABN: 50 005 085 521 Wollongong QS1081_R0 +61 2 9900 8492 . -

Submission To: Victorian Bushfire Inquiry

Submission to: Victorian Bushfire Inquiry Addressed to: Tony Pearce; Inspector-General Emergency Management, Victoria Submission from: Emergency Leaders for Climate Action https://emergencyleadersforclimateaction.org.au/ Prepared on behalf of ELCA by: Greg Mullins AO, AFSM; Former Commissioner, Fire & Rescue NSW May 2020 1 About Emergency Leaders for Climate Action Climate change is escalating Australia’s bushfire threat placing life, property, the economy and environment at increasing risk. Emergency Leaders for Climate Action (ELCA) was formed in April 2019 due to deep shared concerns about the potential of the 2019/20 bushfire season, unequivocal scientific evidence that climate change is the driver of longer, more frequent, more intense and overlapping bushfire seasons, and the failure of successive governments, at all levels, to take credible, urgent action on the basic causal factor: greenhouse gas emissions from the burning of coal, oil and gas. Greenhouse emissions are causing significant warming, in turn worsening the frequency and severity of extreme weather events that exacerbate and drive natural disasters such as bushfires. ELCA originally comprised of 23 former fire and emergency service leaders from every state and territory and every fire service in Australia, from several State Emergency Service agencies, and from several forestry and national parks agencies. At the time of submission, ELCA continues to grow and now comprises 33 members, including two former Directors General of Emergency Management Australia. Cumulatively, ELCA represents about 1,000 years of experience. Key members from Victoria include: • Craig Lapsley PSM: Former Emergency Management Commissioner; Former Fire Services Commissioner; Former Deputy Chief Officer, Country Fire Authority. • Russell Rees AFSM: Former Chief Fire Officer, Country Fire Authority Victoria. -

Nineteenth-Century Lunatic Asylums in South Australia and Tasmania (1830-1883)

AUSTRALASIAN HISTORICAL ARCHAEOLOGY, 19,2001 Convicts and the Free: Nineteenth-century lunatic asylums in South Australia and Tasmania (1830-1883) SUSAN PIDDOCK While most ofus are familiar with the idea ofthe lunatic asylum, few people realise that lunatic asylums were intended to be curative places where the insane were return to sanity. In the early nineteenth century a new treatment regime that emphasised the moral management of the insane person in the appropriate environment became popular. This environment was to be provided in the new lunatic asylums being built. This article looks at what this moral environment was and then considers it in the context ofthe provisions made for the insane in two colonies: South Australia and Tasmania. These colonies had totally different backgrounds, one as a colony offree settlers and the other as a convict colony. The continuing use ofnineteenth-century lunatic asylums as modern mental hospitals means that alternative approaches to the traditional approaches ofarchaeology have to be considered, and this article discusses documentary archaeology as one possibility. INTRODUCTION and Australia. In this paper a part of this study is highlighted, that being the provision of lunatic asylums in two colonies of While lunacy and the lunatic asylum are often the subject of Australia: South Australia and Tasmania. The first a colony academic research, little attention has been focused on the that prided itself on the lack of convicts within its society, and asylums themselves, as built environments in which the insane the second a colony which received convicts through the were to be bought back to sanity and returned to society. -

Number of Living Species in Australia and the World

Numbers of Living Species in Australia and the World 2nd edition Arthur D. Chapman Australian Biodiversity Information Services australia’s nature Toowoomba, Australia there is more still to be discovered… Report for the Australian Biological Resources Study Canberra, Australia September 2009 CONTENTS Foreword 1 Insecta (insects) 23 Plants 43 Viruses 59 Arachnida Magnoliophyta (flowering plants) 43 Protoctista (mainly Introduction 2 (spiders, scorpions, etc) 26 Gymnosperms (Coniferophyta, Protozoa—others included Executive Summary 6 Pycnogonida (sea spiders) 28 Cycadophyta, Gnetophyta under fungi, algae, Myriapoda and Ginkgophyta) 45 Chromista, etc) 60 Detailed discussion by Group 12 (millipedes, centipedes) 29 Ferns and Allies 46 Chordates 13 Acknowledgements 63 Crustacea (crabs, lobsters, etc) 31 Bryophyta Mammalia (mammals) 13 Onychophora (velvet worms) 32 (mosses, liverworts, hornworts) 47 References 66 Aves (birds) 14 Hexapoda (proturans, springtails) 33 Plant Algae (including green Reptilia (reptiles) 15 Mollusca (molluscs, shellfish) 34 algae, red algae, glaucophytes) 49 Amphibia (frogs, etc) 16 Annelida (segmented worms) 35 Fungi 51 Pisces (fishes including Nematoda Fungi (excluding taxa Chondrichthyes and (nematodes, roundworms) 36 treated under Chromista Osteichthyes) 17 and Protoctista) 51 Acanthocephala Agnatha (hagfish, (thorny-headed worms) 37 Lichen-forming fungi 53 lampreys, slime eels) 18 Platyhelminthes (flat worms) 38 Others 54 Cephalochordata (lancelets) 19 Cnidaria (jellyfish, Prokaryota (Bacteria Tunicata or Urochordata sea anenomes, corals) 39 [Monera] of previous report) 54 (sea squirts, doliolids, salps) 20 Porifera (sponges) 40 Cyanophyta (Cyanobacteria) 55 Invertebrates 21 Other Invertebrates 41 Chromista (including some Hemichordata (hemichordates) 21 species previously included Echinodermata (starfish, under either algae or fungi) 56 sea cucumbers, etc) 22 FOREWORD In Australia and around the world, biodiversity is under huge Harnessing core science and knowledge bases, like and growing pressure. -

SA Climate Ready Climate Projections for South Australia

South East SA Climate Ready Climate projections for South Australia This document provides a summary of rainfall The region and temperature (maximum and minimum) information for the South East (SE) Natural Resources The SE NRM region (from the Management (NRM) region generated using the northern Coorong and Tatiara districts latest group of international global climate models. to the coast in the south and west, Information in this document is based on a more and Victoria to the east) has wet, cool detailed regional projections report available winters and dry, mild-hot summers; at www.goyderinstitute.org. with increasing rainfall from north to south; coastal zones are dominated by Climate projections at a glance winter rainfall, whilst more summer rain is experienced in inland areas. The future climate of the SE NRM region will be drier and hotter, though the amount of global action on decreasing greenhouse The SA Climate Ready project gas emissions will influence the speed and severity of change. The Goyder Institute is a partnership between the South Decreases in rainfall are projected for all seasons, Australian Government through the Department of Environment, with the greatest decreases in spring. Water and Natural Resources, CSIRO, Flinders University, Average temperatures (maximum and minimum) are University of Adelaide, and the University of South Australia. projected to increase for all seasons. Slightly larger increases In 2011, the Goyder Institute commenced SA Climate Ready, in maximum temperature occur for the spring season. a project to develop climate projections for South Australia. The resulting information provides a common platform on which Government, business and the community can By the end of the 21st century develop solutions to climate change adaptation challenges. -

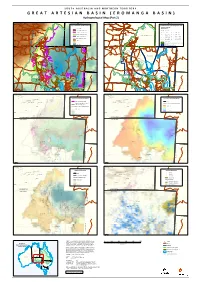

GREAT ARTESIAN BASIN Responsibility to Any Person Using the Information Or Advice Contained Herein

S O U T H A U S T R A L I A A N D N O R T H E R N T E R R I T O R Y G R E A T A R T E S I A N B A S I N ( E RNturiyNaturiyaO M A N G A B A S I N ) Pmara JutPumntaara Jutunta YuenduYmuuendumuYuelamu " " Y"uelamu Hydrogeological Map (Part " 2) Nyirri"pi " " Papunya Papunya ! Mount Liebig " Mount Liebig " " " Haasts Bluff Haasts Bluff ! " Ground Elevation & Aquifer Conditions " Groundwater Salinity & Management Zones ! ! !! GAB Wells and Springs Amoonguna ! Amoonguna " GAB Spring " ! ! ! Salinity (μ S/cm) Hermannsburg Hermannsburg ! " " ! Areyonga GAB Spring Exclusion Zone Areyonga ! Well D Spring " Wallace Rockhole Santa Teresa " Wallace Rockhole Santa Teresa " " " " Extent of Saturated Aquifer ! D 1 - 500 ! D 5001 - 7000 Extent of Confined Aquifer ! D 501 - 1000 ! D 7001 - 10000 Titjikala Titjikala " " NT GAB Management Zone ! D ! Extent of Artesian Water 1001 - 1500 D 10001 - 25000 ! D ! Land Surface Elevation (m AHD) 1501 - 2000 D 25001 - 50000 Imanpa Imanpa ! " " ! ! D 2001 - 3000 ! ! 50001 - 100000 High : 1515 ! Mutitjulu Mutitjulu ! ! D " " ! 3001 - 5000 ! ! ! Finke Finke ! ! ! " !"!!! ! Northern Territory GAB Water Control District ! ! ! Low : -15 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! FNWAP Management Zone NORTHERN TERRITORY Birdsville NORTHERN TERRITORY ! ! ! Birdsville " ! ! ! " ! ! SOUTH AUSTRALIA SOUTH AUSTRALIA ! ! ! ! ! ! !!!!!!! !!!! D !! D !!! DD ! DD ! !D ! ! DD !! D !! !D !! D !! D ! D ! D ! D ! D ! !! D ! D ! D ! D ! DDDD ! Western D !! ! ! ! ! Recharge Zone ! ! ! ! ! ! D D ! ! ! ! ! ! N N ! ! A A ! L L ! ! ! ! S S ! ! N N ! ! Western Zone E -

Redefining Southern Australia´S Climatic Regions and Seasons

CSIRO PUBLISHING Journal of Southern Hemisphere Earth Systems Science, 2021, 71, 92–109 https://doi.org/10.1071/ES20003 Redefining southern Australia’s climatic regions and seasons Sonya Fiddes A,B,D, Acacia Pepler A, Kate Saunders C and Pandora Hope A ABureau of Meteorology, Melbourne, Australia. BPresent Address. Australian Antarctic Program Partnership, Institute of Marine and Antarctic Studies, University of Tasmania, Hobart, Australia. CDelft Institute of Applied Mathematics, Delft University of Technology, Delft, Netherlands. DCorresponding author. Email: [email protected] Abstract. Climate scientists routinely rely on averaging over time or space to simplify complex information and to concisely communicate findings. Currently, no consistent definitions of ‘warm’ or ‘cool’ seasons for southern Australia exist, making comparisons across studies difficult. Similarly, numerous climate studies in Australia use either arbitrarily defined areas or the Natural Resource Management (NRM) clusters to perform spatial averaging. While the NRM regions were informed by temperature and rainfall information, they remain somewhat arbitrary. Here we use weather type influence on rainfall and clustering methods to quantitatively define climatic regions and seasons over southern Australia. Three methods are explored: k-means clustering and two agglomerative clustering methods, Ward linkage and average linkage. K-means was found to be preferred in temporal clustering, while the average linkage method was preferred for spatial clustering. For southern Australia as a whole, we define the cool season as April–September and warm season as October–March, though we note that a three-season split may provide more nuanced climate analysis. We also show that different regions across southern Australia experience different seasons and demonstrate the changing spatial influence of weather types with the seasons, which may aid regionally or seasonally specific climate analysis. -

Eubalaena Australis) in SouthEastern Australia

IWC | J. Cetacean. Res. Manage. 22, 2021 | 17 Calving intervals, longrange movements and site fidelity of southern right whales (Eubalaena australis) in southeastern Australia M. WATSON1*, K. STAMATION2, C. CHARLTON3 AND J. BANNISTER Contact e‐mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT Southern right whales in south‐eastern Australia are endangered and vulnerable to impacts from human disturbance. Information on population demographics and movement data is needed to inform ongoing species management. While the number of whales observed using the south‐eastern Australian coastline is increasing, there has been no change over three decades in the annual abundance of cow‐calf pairs at Logans Beach in Warrnambool, Victoria, the only established calving ground in south‐east Australia. Knowledge of life history parameters of the south‐eastern Australian subpopulation is lacking. Here, we examine sightings and photo‐identification data from southern Australia to investigate calving intervals, long range movements and fidelity to the Logans Beach calving ground. Sightings data revealed at least 93 calves were born at Logans Beach between 1980 and 2018 (an average of 2.6 per year) with a mean calving interval of 3.5 ± 0.2 years (± SE, n = 34). Comparison between photo‐identification catalogues compiled for south‐eastern and south‐western Australia shows that southern right whales are wide ranging within southern Australian waters. Females can be sighted at locations as far apart as 3,800km across seasons with at least 7% of whales using both regions. We also provide the first report of an Australian southern right whale female belonging to one subpopulation relocating long‐term to a calving area in another.