Value Chain Analysis for the Coffee Sector in Rwanda Report for the CBI – 27 July 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

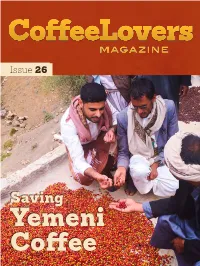

The Journey of One Man Trying to Save Yemeni Coffee (2015)

Issue 26 Saving Yemeni Coffee Coffee at its Origin The journey of one man trying to save Yemeni Coffee Ummah Wide Interviews Mokhtar Alkhanshali of Mocha Mill ummah wide: We are with Mokhtar mokhtar alkhanshali: I was recently talking Alkhanshali, the President and Founder of Mocha to one of my childhood mentors, Nasseam Mill — Yemeni Speciality Coffee, a company with a Elkarra, and he was reminding me that when I powerful social mission that is bridging the worlds was in High School I was always talking about of coffees roots in Yemen with the speciality coffee coffee in Yemen and the history of coffee in industry in the United States. One of the incredible Yemen. In particular he said I was talking things about this project is that you stand at the about the issue of Qat, the locally consumed intersection of two amazing histories, on one side stimulant in Yemen and how it’s taken the place you come from a family who has been growing of coffee in agriculture and someone needs to coffee for hundreds of years in Yemen, the first do something about it. Stephen Ezill, one of place to cultivate and commercialize coffee in the my friends at Boot Coffee said that his brother world. On the other side you are the first Arab/ called me a hero of a thousand faces because Yemeni certified speciality coffee Q grader. What there are so many different ways of looking can you tell us about these two worlds and how at what I am doing and different routes that you came to this moment in your life founding guided me to this point here. -

Roaster Guild Certification Program Handbook

Coffee Taster CERTIFICATE PROGRAM (CT) Ver. 1.0/January 2013 Specialty Coffee Association of America Cupper Guild of America 330 Golden Shore, Suite 50, Long Beach, California 90802 TEL: 562-624-4193 FAX: 562-624-4101 Introduction to the Coffee Taster (CT) Certificate Program Guide Welcome to the CT Certificate Program of Specialty Coffee Association of America. This guide is to provide general information to candidates of the program. It contains background information, definitions, descriptions, and procedures for the program. TABLE OF CONTENTS CT INFORMATION: Background ................................................................................................................... 1 CT CERTIFICATE PROGRAM: Overview, Purpose, Eligibility and Requirements .................................... 2 CT CERTIFICATE PROGRAM: Curriculum Summary .................................................................................. 3 MODULE 1 : Overview ..................................................................................................................................... 4 MODULE 1 : Classes, Rationale and Expectations ...................................................................................... 5 MODULE 2 : Overview ..................................................................................................................................... 6 MODULE 2 : Classes, Rationale and Expectations ...................................................................................... 7 MODULE 3 : Overview .................................................................................................................................... -

Impact of Temperature and Rainfall Variability on Coffee Production in Maraba

IMPACT OF TEMPERATURE AND RAINFALL VARIABILITY ON COFFEE PRODUCTION IN MARABA BUGINGO Samuel College of Science and Technology School of Science Master of Science in Atmospheric and Climate Science 2018 i IMPACT OF TEMPERATURE AND RAINFALL VARIABILITY ON COFFEE PRODUCTION IN MARABA By BUGINGO Samuel Registration Number: 217290795 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE ATMOSPHERIC AND CLIMATE SCIENCE College of Science and Technology Supervisor: Prof. Bonfils SAFARI August, 201 ii DECLARATION I declare that this Dissertation contains my own work except where specifically acknowledged. BUGINGO Samuel Reg. Number: 217290795 Signed……………………………………….. Date………………………………………….. i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The completion of this work has been made possible through the assistance and cooperation of several people. First, gratitude goes to my supervisor Prof. Bonfils SAFARI for his guidance and support throughout my study, I am highly appreciating his initiative for the existence of master's program in atmospheric and climate science in University of Rwanda. My special thanks go to Abahuzamugambi Ba Kawa Cooperative for providing data for the study. I am also highly indebted to others for their assistance and support. I appreciate the sacrifice made by Mr NYIRIMANA Bernard a farmer and one of the pioneers of Abahuzamugambi Ba Kawa cooperative in Maraba for his answers to my questions. I would also like to thank vastly all my colleagues for their assistance, support and for providing a good working environment. To all my classmates: I enjoyed the resourceful and thought provoking discussions we had together on a wide range of issues. And last but not least, I am grateful for my friends and family for their endless support, especially IRATUZI Rachel for her love, advice and encouragement. -

Ulk Scientific Journal Vol. 36

KIGALI INDEPENDENT UNIVERSITY ULK P.O BOX: 2280 KIGALI Tel: 0788304081/0788304084 Website: http://www.ulk.ac.rw E-mail:[email protected] ULK SCIENTIFIC JOURNAL VOL. 36 ISSN 2308-5843 EDITIONS OF THE KIGALI INDEPENDENT UNIVERSITY ULK May, 2017 -1- ULK SCIENTIFIC JOURNAL VOL. 32, 2015 DISCLAIMER Views expressed in this publication are personal views of the article authors and do not necessarily reflect views of ULK. -2- 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Fair Trade Certified Coffee Cooperatives and Socio - Economic Development of Farmers in Rwanda: A case study of Maraba Coffee Cooperative By: Dr MBERA R Zenon NTIHINYURWA Arcade Interdisciplinary Approach between Law and Science Technology for Sustainable Development of Justice in Rwanda: A new Legal Perspective By: Dr. Murangira B. Thierry Effects of Customer Satisfaction on Financial Performance of Financial Institutions: Case of BPR, Nyamagabe Branch(2013-2015) By: Dr. RUTUNGWA Eugène HABAKUBANA Egide The role of Monitoring and Evaluation to Construction Projects Success in Rwanda A Case of Genocide Survivors’ Settlement Project in Gasabo District By: Dr MBERA R Zenon MUTIGANDA Onesphore -3- -4- FAIR TRADE CERTIFIED COFFEE COOPERATIVES AND SOCIO - ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT OF FARMERS IN RWANDA A CASE STUDY OF MARABA COFFEE COOPERATIVE Authors: Dr MBERA R Zenon1 NTIHINYURWA Arcade2 1 Researcher & Academician, ULK – Republic of Rwanda 2 Researcher & Consultant -5- ABSTRACT Coffee is the most valuable and widely traded tropical agricultural product, but many of farmers fail to earn a reliable living from coffee. Farmers are frequently reported to be trapped in the vicious cycle of lack of profitability and lack of access to finance. -

ACDI/VOCA Rwanda PL 480, Title II Monetization Development Program

Final Evaluation of ACDI/VOCA Rwanda P.L 480, Title II Monetization Development Program (2000-2005) Transfer Authorization FFP-A-00-00-00037-00 Development Assistance Grant No. 623-G-00-00-00119-00 Prepared by: Dr. Richard Swanson Prepared for: ACDI/VOCA 50 F Street, NW, Suite 1100 Washington, DC 20001 Phone: 202/638-4661 Fax: 202/626-8726 October 2004 2 3 List of Acronyms ACDI/VOCA or A/V Agricultural Cooperative Development International/Volunteer Overseas Cooperative Assistance ADAR Assistance à la Dynamisation de l’Agriculture au Rwanda (Chemonics Int. USAID project) ADP Area Development Program ADRI Association de Développement Rurale Integrée AJENI Association Association des Jeunes Pour des Nouvelles Initiatives Communautaires APROJUFUGI Association des Producteurs de Jus de Fruits de Gishoma APREKA Association pour la Promotion de l’Education dans le District de Kayove ATDT Agricultural Technology Development & Transfer Project (USAID funded project – International Center for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT)) BRD Banque Rwandaise de Développement (Rwandan Development Bank) CDC Community Development Council COOPAC Coopérative pour la Promotion des Activités - Café COVEPAR Coopérative de Va lorisation et d’Exportations des Produits Agricoles Rwandais (Manioc flour) in Butare (PEARL leadership) COPIBAL-KIVU Coopérative pour la Promotion de la Pisciculture Integrée dans les Baies du Lac Kivu COPROVAB Coopérative pour la Promotion et la Valoris ation de la Culture de Blé CPCRB Coopérative pour la Promotion de la Culture du Riz dans le District -

Effects of Coffee Roasting Technologies on Bioactive Compounds and Cup Quality of Specialty Coffee Beans Grown in Ethiopia

ADDIS ABABA UNIVERSITY ADDIS ABABA INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY SCHOOL OF CHEMICAL AND BIO-ENGINEERING FOOD ENGINEERING PROGRAMME Effects of Coffee Roasting Technologies on Bioactive Compounds and Cup Quality of Specialty Coffee Beans Grown in Ethiopia A Thesis Submitted to the School of Chemical & Bio-Engineering in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science (M.Sc.) in Chemical Engineering (Food Engineering) By Muluken Zenebe Bolka November 7, 2019 Addis Ababa, Ethiopia Effects of Coffee Roasting Technologies on Bioactive Compounds and Cup Quality of Specialty Coffee Beans Grown in Ethiopia By Muluken Zenebe Bolka A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science (M.Sc.) in Chemical Engineering (Food Engineering) School of Chemical and Bio-Engineering Addis Ababa Institute of Technology Addis Ababa University Advisor: Dr. Eng. Shimelis Admassu (Associate Professor) Title Page Copyright © Muluken Z. Bolka, 2019 i Declaration I, the undersigned, declare that this thesis presented for the attainment of the degree of Master of Science in Chemical Engineering (Food Engineering) has been composed solely by myself and has not been presented or submitted, in part or as a whole, for a degree in any other institution or university. The thesis presented is my original work and all sources of information or materials used for the thesis have been duly acknowledged. Mr. Muluken Zenebe Bolka Signature: _______________ Date: ___________________ M.Sc. Candidate This thesis has been submitted for examination with my approval and done under my supervision as University advisor. Dr. Eng. Shimelis Admassu Emire Signature: ______________ Date: ____________________ Advisor The undersigned members of the thesis examining board appointed to examine the thesis of Mr. -

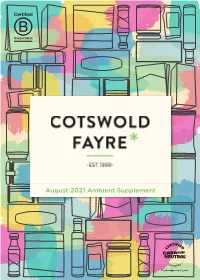

Ambient Supplement

August 2021 Ambient Supplement We are all becoming more aware of the devastating impact UNPACKAGED FULL RANGE of plastic pollution on our environment - the equivalent of GRAVITY OR AMBIENT OR Bulk Loose Products PRICE UNIT a truckload of plastic enters our seas every single minute. DISPENSER SEASONAL Most plastic packaging is single-use and not recyclable. WWF10 Cereals Z Bulk - Apricot & Cranberry Granola 3 x 2.5kg £29.40 £0.39 Either Ambient Your customers are crying out for a different way to shop and WWF11 Cereals Z Bulk - Nutty Crunch Granola 3 x 2.5kg £29.40 £0.39 Either Ambient HOD112 Cereals Z Hodmedod's - Organic Muesli Base, Four Grain 1 x 3kg £12.20 £0.41 Either Ambient no doubt, sustainability is high on your list of priorities as a HOD113 Cereals Z Hodmedod's - Organic Rye Flakes 1 x 3kg £7.60 £0.25 Gravity Ambient business, too. HOD114 Cereals Z Hodmedod's - Organic Rolled Oats 1 x 3kg £8.00 £0.27 Gravity Ambient HOD115 Cereals Z Hodmedod's - Organic Jumbo Oats 1 x 3kg £8.00 £0.27 Gravity Ambient WWF01 Dried Fruit Z Bulk - Selected Dried Apricots 3 x 3kg £48.15 £0.54 Scoop Ambient WWF02 Dried Fruit Z Bulk - Lerida Figs 8 x 1kg £56.00 £0.70 Scoop Ambient This year, Cotswold Fayre and Unpackaged have launched WWF03 Dried Fruit Z Bulk - Dried Apple 4 x 2.5kg £78.20 £0.78 Scoop Ambient UnpackagedAT, a one-stop shop solution to help independent WWF12 Dried Fruit Z Bulk - Sundried Mango 4 x 1kg £61.60 £1.54 Scoop Ambient WWF20 Dried Fruit Z Bulk - Dates 1 x 5kg £21.65 £0.43 Scoop Ambient retailers reduce single-use plastic packaging in store. -

Coffee Flavor and Flavor Attributes That Drive Consumer Liking for These Novel Products

beverages Review Coffee Flavor: A Review Denis Richard Seninde and Edgar Chambers IV * Center for Sensory Analysis and Consumer Behavior, Kansas State University, Manhattan, KS 66502, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 1 June 2020; Accepted: 3 July 2020; Published: 8 July 2020 Abstract: Flavor continues to be a driving force for coffee’s continued growth in the beverage market today. Studies have identified the sensory aspects and volatile and non-volatile compounds that characterize the flavor of different coffees. This review discusses aspects that influence coffee drinking and aspects such as environment, processing, and preparation that influence flavor. This summary of research studies employed sensory analysis (either descriptive and discrimination testing and or consumer testing) and chemical analysis to determine the impact aspects on coffee flavor. Keywords: coffee flavor; processing; preparation; emotion; environment; consumer acceptance 1. Introduction The coffee market is currently worth USD 15.1 billion and growing. This market is mainly comprised of roasted, instant, and ready-to-drink (RTD) coffee [1]. The flavor of a roasted coffee brew is influenced by factors such as the geographical location of origin, variety, climatic factors, processing methods, roasting process, and preparation methods [2–10]. The differences in sensory properties can, in turn, affect consumers’ preferences for and emotions or attitudes toward coffee drinking [11]. 1.1. Motivations for Drinking Coffee As indicated by Phan [12], the motivations for drinking coffee can be grouped under 17 constructs: liking, habits, need and hunger, health, convenience, pleasure, traditional eating, natural concerns, sociability, price, visual appeal, weight control, affect regulation, social norms, social image [13], choice and variety seeking [12,14,15]. -

Extract Series TEMPLATE: COFFEE & MILK

Extract Series TEMPLATE: COFFEE & MILK THaveaste andyou evercompa tastedre 3 d2i fmilksferent side sugars by sideat 3 anddiffe wonderedrent levels howof refinement, they could t henbe seeso different? how each sugar impacts the flavor of two or more coffees with different flavor profiles. Or had the same coffee at 2 different shops that use different milks and Materials:wondered whyRefined the cappuccinossugar, Turbinado highlighted sugar, Sucanat/Deme totally differentrera/Muscavado flavors? sugar, small tasting cups or spoons for sugars, small tasting cups for coffees, scales,In this exercise,grinders, you’llbrewing compare and service the taste for coof fmilksfees. from 3 different dairies. Prepare like a coffee cupping and have attendees taste with cupping spoons. PEachrovide of thea brief 3 milks introduc shouldtion be of prepared the exercise, cold briefly and steamed. describing Optional: the following: Also prepare each of the 3 milks as a cappuccino with the same coffee/recipe for each. • Why are we doing the exercise • What items will be tasted This exercise• What toworks reflect best upon if you as canyou’ includere tasting at least(sensory 1 totally sensa differenttions, intensity milk. vs. Non-homogonized,flavor) UHT Pasteurization, All Jersey Cows, or something attendees• Best might prac tnotices have for exe accessrcise to (tas att ingtheir o rcafé.der, tasting multiple times, tasting at different dosages) Materials: 3 different milks from 3 different dairies, cupping spoons, glasses Pforrocedu all milkres: samples, buckets for dumping, rinse water, towels, espresso machine equipment for steaming the milk and/or preparing coffee. 1. Taste the sugars. Provide a brief introduction of the exercise, briefly describing the following:• Refined Sugar - Full refinement, only sucrose is left. -

How Business Strategy Is Transforming Rwanda

How Business Strategy is Transforming Rwanda NEAL DONAHUE "Hope is definitely not the same thing as optimism. 'It is not the conviction that something will turn out well, but the certainty that something makes sense, regardless of how it turns out. -VACLAV HAVEL In July 1994, forces of the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) entered Kigali and ended a genocide that took the lives of 800,000 Tutsis and moderate Hutus. The military actions of the RPF, the creation of the government of national unity, and the assistance of international donors restored hope to Rwanda. Millions of displaced people returned to Rwanda and began the effort to rebuild their lives. Over the past decade, Rwanda has used this hope to build a new society and create the foundation of a stable economy. Rwanda's economy grew steadily during the last decade, and the standard of living is slowly improving. The Government of Rwanda has set the target of achieving middle income status by 2020. To achieve this ambitious goal, Rwanda must have a GDP per capita of US$900/year. Assuming the population continues to grow at recent historic rates, Rwanda will have 16 million citizens in 2020. Taken together, that means that the economy of Rwanda must grow from its US$2 billion in 2000 to almost US$14.5 billion in 2020. What can Rwanda do to sustain a required growth rate of 8 percent per year? A nation's standard of living is determined by its productivity-that is, how well its citizens work together to create value for foreign customers and for one another. -

Quantitative Analysis of Caffeine Content from Coffee Growing in Different Regions of Rwanda

© IJARW | ISSN (O) - 2582-1008 July 2021 | Vol. 3 Issue. 1 www.ijarw.com QUANTITATIVE ANALYSIS OF CAFFEINE CONTENT FROM COFFEE GROWING IN DIFFERENT REGIONS OF RWANDA. 1 2 3 Barasikina Jean d’Amour , Kagiraneza Olivier Placide , NSHOGOZ Gilbert 1University of Rwanda /College of Science and Technology, Department of Chemistry, POBX: 3900 Kigali-Rwanda 2Eduardo Mondlane University, Department of Chemical Engineering, postal 257 Maputo- Mozambique 3lecturer at University of Rwanda-College of Science and Technology. ABSTRACT Coffea is considered as a large genus (with more than 90 species) of flowering plants belongs in the family Rubiaceae. However, coffee ranks as one of the major commodity crops in the world and is the essential export product of some countries. Moreover, coffee beans found on the market are produced from two different species of the Coffea genus such as Coffea arabica and Coffea canephora syn. Coffea robusta . Nowadays, due to its pleasant taste, aroma, stimulant effect, and health benefits, coffee is one among the most widely consumed beverages throughout the world includes Rwanda country. Both species of coffee present a rich source of biologically active compounds such as caffeine. Caffeine is defined as a xanthine alkaloid compound that acts as a stimulant in humans. It is normally found in the leaves and beans of the coffee plant. In addition to that, caffeine is widely used to enhance alertness and improve performance as it acts as psychostimulant. Consequently, the strong pharmacological effects of caffeine have led to consumer demand for caffeine- free coffee beverages. Due to the high consumption rate of caffeine and its potential physiological effects, both health professionals and consumers need to know the exact caffeine content in food. -

Charlotte's Coffee House

DUBUQUE365.com CHARLOTTE’S COFFEE HOUSE BY RICH BelMONT With new coffee shops popping up all over Dubuque you might Obviously there is a list of coffee beverages to choose from. them to throw in mushrooms not have noticed Charlotte’s Coffee House at the corner of 11th Of course brewed coffee is always available but the real fun and tomatoes too. At lunch and White Streets. It has been in operation for six months and is in trying the specialties. Here are some you might not be time I prefer the Turkey & already has a devoted following of coffee aficionados. familiar with: Dressing Panini. This one has roasted turkey, Monterey Don Rusk and his wife, Espresso (ehss-press-oh) – a strong, thick, syrupy coffee Jack or Swiss cheese, sage Cheryl, are Dubuque natives made by forcing nearly boiling water under pressure through dressing, cranberry sauce and the owners of Charlotte’s tightly packed finely ground coffee beans. and pesto. It was supposed to Coffee House. Don also owns be a seasonal special for Thanksgiving but so many customers and operates Rusk Metal Cappuccino (cap-poo-chee-no) – prepared with espresso, hot kept asking for it they had to add it to the regular menu. Company in Epworth, IA. milk and steamed milk foam. (Fun Fact: the foam on top acts He has been in the metal as an insulator and helps retain the heat of the espresso By the way do you know how we got to enjoy a Panini? Panini business for over 20 years. allowing it to stay hotter longer.) (pah-nee-nee) is the plural of the Italian word Panino or bread Cheryl recently retired from John Deere Dubuque Works where roll.