A Thesis Submi Tted Ta the Facul Ty of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Degree Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Encyclopedia of Jews in the Islamic World

EJIW Encyclopedia of Jews in the Islamic World 5 volumes including index Executive Editor: Norman A. Stillman Th e goal of the Encyclopedia of Jews in the Islamic World is to cover an area of Jewish history, religion, and culture which until now has lacked its own cohesive/discreet reference work. Th e Encyclopedia aims to fi ll the gap in academic reference literature on the Jews of Muslims lands particularly in the late medieval, early modern and modern periods. Th e Encyclopedia is planned as a four-volume bound edition containing approximately 2,750 entries and 1.5 million words. Entries will be organized alphabetically by lemma title (headword) for general ease of access and cross-referenced where appropriate. Additionally the Encyclopedia of Jews in the Islamic World will contain a special edition of the Index Islamicus with a sole focus on the Jews of Muslim lands. An online edition will follow aft er the publication of the print edition. If you require further information, please send an e-mail to [email protected] EJIW_Preface.indd 1 2/26/2009 5:50:12 PM Australia established separate Sephardi institutions. In Sydney, the New South Wales Association of Sephardim (NAS), created in 1954, opened Despite the restrictive “whites-only” policy, Australia’s fi rst Sephardi synagogue in 1962, a Sephardi/Mizraḥi community has emerged with the aim of preserving Sephardi rituals in Australia through postwar immigration from and cultural identity. Despite ongoing con- Asia and the Middle East. Th e Sephardim have fl icts between religious and secular forces, organized themselves as separate congrega- other Sephardi congregations have been tions, but since they are a minority within the established: the Eastern Jewish Association predominantly Ashkenazi community, main- in 1960, Bet Yosef in 1992, and the Rambam taining a distinctive Sephardi identity may in 1993. -

Research Guide to Holocaust-Related Holdings at Library and Archives Canada

Research guide to Holocaust-related holdings at Library and Archives Canada August 2013 Library and Archives Canada Table of Contents INTRODUCTION...................................................................................................... 4 LAC’S MANDATE ..................................................................................................... 5 CONDUCTING RESEARCH AT LAC ............................................................................ 5 HOW TO USE THIS GUIDE ........................................................................................................................................ 5 HOW TO USE LAC’S ONLINE SEARCH TOOLS ......................................................................................................... 5 LANGUAGE OF MATERIAL.......................................................................................................................................... 6 ACCESS CONDITIONS ............................................................................................................................................... 6 Government of Canada records ................................................................................................................ 7 Private records ................................................................................................................................................ 7 NAZI PERSECUTION OF THE JEWISH BEFORE THE SECOND WORLD WAR............... 7 GOVERNMENT AND PRIME MINISTERIAL RECORDS................................................................................................ -

Knowing When a Higher Education Institution Is in Trouble Pamela S

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar Theses, Dissertations and Capstones 1-1-2005 Knowing When a Higher Education Institution is in Trouble Pamela S. Sturm [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://mds.marshall.edu/etd Part of the Higher Education Administration Commons Recommended Citation Sturm, Pamela S., "Knowing When a Higher Education Institution is in Trouble" (2005). Theses, Dissertations and Capstones. Paper 367. This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses, Dissertations and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. KNOWING WHEN A HIGHER EDUCATION INSTITUTION IS IN TROUBLE by Pamela S. Sturm Dissertation submitted to The Graduate College of Marshall University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Education in Educational Leadership Approved by Powell E. Toth, Ph. D., Chair R. Charles Byers, Ph. D. John L. Drost, Ph. D. Jerry D. Jones, Ed. D. Department of Leadership Studies 2005 Keywords: Institutional Closure, Logistic Regression, Institutional Viability Copyright 2005 Pamela S. Sturm All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT KNOWING WHEN A HIGHER EDUCATION INSTITUTION IS IN TROUBLE by Pamela S. Sturm This study investigates factors that measure the institutional viability of higher education organizations. The purpose of investigating these measures is to provide higher education officials with a means to predict the likelihood of the closure of a higher education institution. In this way, these viability measures can be used by administrators as a warning system for corrective action to ensure the continued viability of their institutions. -

G B a W H D F J Z by Ay Y

This is the Path Twelve Step in a Jewish Context g b a w h d f j z by ay y Rabbi Rami Shapiro 1 –––––––––––––––– 12 Steps in a Jewish Context This is the Path © 2005 by Rabbi Rami M. Shapiro. All rights reserved. Any part of this manual may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, or any retrieval system, without the written permission of the author as long as credit is given to the author and mention is made of the Gerushin Workshop for which this manual was created. 2 –––––––––––––––– 12 Steps in a Jewish Context 1 INTRODUCTION Then your Guide will no more be ignored, and your eyes will watch your Guide, and whenever you deviate to the right or to the left, your ears will heed the command from behind you: "This is the path, follow it!" - Isaiah 30:20-21 Over the past few years, I have come into contact with ever greater numbers of Jews involved in Twelve Step Programs. I am always eager to listen to the spiritual trials these people undergo and am amazed at and inspired by their courage. Often, as the conversation deepens, a common concern emerges that reveals a sense of uneasiness. For many Twelve Step participants, despite the success of their labors, the Twelve Steps somehow strike them as un-Jewish. For many participants, the spiritual element of the Twelve Steps has a decidedly Christian flavor. There may be a number of reasons for this, not the least of which is the fact that churches often provide the setting for meetings. -

אוסף מרמורשטיין the Marmorstein Collection

אוסף מרמורשטיין The Marmorstein Collection Brad Sabin Hill THE JOHN RYLANDS LIBRARY UNIVERSITY OF MANCHESTER Manchester 2017 1 The Marmorstein Collection CONTENTS Acknowledgements Note on Bibliographic Citations I. Preface: Hebraica and Judaica in the Rylands -Hebrew and Samaritan Manuscripts: Crawford, Gaster -Printed Books: Spencer Incunabula; Abramsky Haskalah Collection; Teltscher Collection; Miscellaneous Collections; Marmorstein Collection II. Dr Arthur Marmorstein and His Library -Life and Writings of a Scholar and Bibliographer -A Rabbinic Literary Family: Antecedents and Relations -Marmorstein’s Library III. Hebraica -Literary Periods and Subjects -History of Hebrew Printing -Hebrew Printed Books in the Marmorstein Collection --16th century --17th century --18th century --19th century --20th century -Art of the Hebrew Book -Jewish Languages (Aramaic, Judeo-Arabic, Yiddish, Others) IV. Non-Hebraica -Greek and Latin -German -Anglo-Judaica -Hungarian -French and Italian -Other Languages 2 V. Genres and Subjects Hebraica and Judaica -Bible, Commentaries, Homiletics -Mishnah, Talmud, Midrash, Rabbinic Literature -Responsa -Law Codes and Custumals -Philosophy and Ethics -Kabbalah and Mysticism -Liturgy and Liturgical Poetry -Sephardic, Oriental, Non-Ashkenazic Literature -Sects, Branches, Movements -Sex, Marital Laws, Women -History and Geography -Belles-Lettres -Sciences, Mathematics, Medicine -Philology and Lexicography -Christian Hebraism -Jewish-Christian and Jewish-Muslim Relations -Jewish and non-Jewish Intercultural Influences -

Schreiber QX

AARON M. SCHREIBER The H. atam Sofer’s Nuanced Attitude Towards Secular Learning, Maskilim, and Reformers Introduction abbi Moshe Sofer (1762-1839), commonly referred to as H. atam RSofer (after the title of his famous halakhic work), served as Rabbi of Pressburg, a major city in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, beginning in 1806. Subsequently, he became one of the principal leaders of the Orthodox Jewish community in Central Europe in the first four decades of the 19th century. R. Sofer was at the forefront of the orthodox strug- gles against the Jewish Reform movement.1 A towering halakhic author- ity whose rulings and opinions were sought by many from near and far, he was also known as a z.addik and as a person of unwavering principles to which he adhered regardless of the personal struggle required.2 He was charismatic and was reputed to be graced with the Divine Spirit, AARON M. SCHREIBER has been a tenured Professor of Law at a number of American law schools, and a founder and Professor of Law at Bar-Ilan University Faculty of Law in Israel. His published books include Jewish Law and Decision Making: A Study Through Time, and Jurisprudence: Understanding and Shaping Law (with W. Michael Reisman of Yale Law School). He has authored numerous articles on law, jurisprudence, and Jewish subjects, and was the Principal Investigator for many years of the computerized Jewish Responsa (She’elot u-Teshuvot) Project at Bar-Ilan University. 123 The Torah u-Madda Journal (11/2002-03) 124 The Torah u-Madda Journal even to receive visions of events in the future and in far away places.3 As a result, he had a profound influence on religious Jewry, particularly in Hungary, Poland, and all of Central Europe, both during and after his lifetime. -

Fine Judaica, to Be Held May 2Nd, 2013

F i n e J u d a i C a . printed booKs, manusCripts & autograph Letters including hoLy Land traveL the ColleCtion oF nathan Lewin, esq. K e s t e n b au m & C om pa n y thursday, m ay 2nd, 2013 K est e n bau m & C o m pa ny . Auctioneers of Rare Books, Manuscripts and Fine Art A Lot 318 Catalogue of F i n e J u d a i C a . PRINTED BOOK S, MANUSCRIPTS, & AUTOGRAPH LETTERS INCLUDING HOLY L AND TR AVEL THE COllECTION OF NATHAN LEWIN, ESQ. ——— To be Offered for Sale by Auction, Thursday, May 2nd, 2013 at 3:00 pm precisely ——— Viewing Beforehand: Sunday, April 28th - 12:00 pm - 6:00 pm Monday, April 29th - 12:00 pm - 6:00 pm Tuesday, April 30th - 10:00 am - 6:00 pm Wednesday, May 1st - 10:00 am - 6:00 pm No Viewing on the Day of Sale This Sale may be referred to as: “Pisgah” Sale Number Fifty-Eight Illustrated Catalogues: $38 (US) * $45 (Overseas) KestenbauM & CoMpAny Auctioneers of Rare Books, Manuscripts and Fine Art . 242 West 30th street, 12th Floor, new york, NY 10001 • tel: 212 366-1197 • Fax: 212 366-1368 e-mail: [email protected] • World Wide Web site: www.Kestenbaum.net K est e n bau m & C o m pa ny . Chairman: Daniel E. Kestenbaum Operations Manager: Jackie S. Insel Client Accounts: S. Rivka Morris Client Relations: Sandra E. Rapoport, Esq. (Consultant) Printed Books & Manuscripts: Rabbi Eliezer Katzman Ceremonial & Graphic Art: Abigail H. -

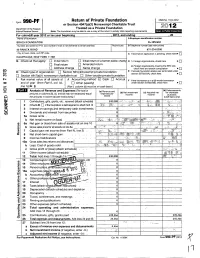

Return of Private Foundation

• t Return of Private Foundation OMB No 1545-0052 Form 990-PF ' or Section 4947(a)(1) Nonexempt Charitable Trust 201 2 Department of the Treasury Treated as a Private Foundation Internal Revenue Service Note . The foundation may be able to use a copy of this return to satisfy state reporting requirements • For calendaf! ,year 2012 or tax year beginning , 2012, and ending , 20 Name of foundation A Employer identification number BRACH FOUNDATION 26-3850684 Number and street (or P 0 box number if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite B Telephone number (see instructions) 40 RANICK ROAD 631-234-5300 City or town, state, and ZIP code q C If exemption application is pending, check here ► HAUPPAUGE, NEW YORK 11788 q q q G Check all that apply: Initial return Initial return of a former public charity D 1. Foreign organizations, check here ► q Final return q Amended return 2. Foreign organizations meeting the 85 % test, q E] Address change [] Name change check here and attach computation ► organization: q Section exempt private foundation E If private foundation status was terminated under H Check type of 501 (c)(3) q section 507(b)(1)(A) , check here ► F1 Section 4947 (a) (1 ) nonexem pt charitable trust q Other taxable private foundation ti Accounting method- i Cash q Accrual Fair market value of all assets at J F If the foundation is in a 60-month termination q end of year (from Part 11, col. (c), q Other (specify) under section 507(b)(1)(B), check here ► line 16) ► $ (Part 1, column (d) must be on cash basis) CD (d) Disbursements -

The Makings of a Ben Torah

The Makings of a Ben Torah Rabbi Dr. Norman Lamm Rabbi Dr. Norman Lamm is Chancellor of Yeshiva University and Rosh HaYeshiva of its affiliated Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary. He was the founding editor of the journal Tradition and, before ascending to the Presidency of Yeshiva University, served for many years as the rabbi of The Jewish Center in New York. Rabbi Lamm recently published The Royal Table: A Passover Haggadah. This essay was originally delivered as a Chag HaSemikhah address in 1983 and reprinted in Moment Magazine, September 1983. To be a rabbi, one must first of all be a ben Torah. What or who is a ben Torah? The translation, “a scholar of the Torah,” does not do the term justice; it is far too restrictive. A better definition would be “a Torah person”—bearing in mind that one cannot truly be a “Torah person” without first being an accomplished Torah scholar. What, then, are the extra ingredients, beyond Talmudic learning, that go to make up a Torah person, a Torah personality? Someone once said that education is what a person has left after he has forgotten all that he has learned. Applying this to a ben Torah, we might then ask what distinguishes a ben Torah from others after you have subtracted all that he has learned of Talmud Bavli and Yerushalmi, of Rashi and Tosafot, of Rishonim and Acharonim, of Rambam and Ramban, of Tur and Shulchan Arukh, of Shakh and Taz, of R. Chaim and R. Akiva Eger. Remove all that and ask: What makes (or should make) us 15 16 Hirhurim Journal different and special? What, in other words, are the attitudinal foundations that inform the mentality of a ben Torah? What, then, are the extra ingredients, beyond Talmudic learning, that go to make up a Torah person, a Torah personality? That is why your overarching commitment is to learn, and then learn more. -

צב | עב January Tevet | Sh’Vat Capricorn Saturn | Aquarius Saturn

צב | עב January Tevet | Sh’vat Capricorn Saturn | Aquarius Saturn Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday 1 | 17th of Tevet* 2 | 18th of Tevet* New Year’s Day Parashat Vayechi Abraham Moshe Hillel Rabbi Tzvi Elimelech of Dinov Rabbi Salman Mutzfi Rabbi Huna bar Mar Zutra & Rabbi Rabbi Yaakov Krantz Mesharshya bar Pakod Rabbi Moshe Kalfon Ha-Cohen of Jerba 3 | 19th of Tevet * 4* | 20th of Tevet 5 | 21st of Tevet * 6 | 22nd of Tevet* 7 | 23rd of Tevet* 8 | 24th of Tevet* 9 | 25th of Tevet* Parashat Shemot Rabbi Menchachem Mendel Yosef Rabbi Moshe ben Maimon Rabbi Leib Mochiach of Polnoi Rabbi Hillel ben Naphtali Zevi Rabbi Shneur Zalman of Liadi Rabbi Yaakov Abuchatzeira Rabbi Yisrael Dov of Vilednik Rabbi Schulem Moshkovitz Rabbi Naphtali Cohen Miriam Mizrachi Rabbi Shmuel Bornsztain Rabbi Eliyahu Eliezer Dessler 10 | 26th of Tevet* 11 | 27th of Tevet* 12 | 28th of Tevet* 13* | 29th of Tevet 14* | 1st of Sh’vat 15* | 2nd of Sh’vat 16 | 3rd of Sh’vat* Rosh Chodesh Sh’vat Parashat Vaera Rabbeinu Avraham bar Dovid mi Rabbi Shimshon Raphael Hirsch HaRav Yitzhak Kaduri Rabbi Meshulam Zusha of Anipoli Posquires Rabbi Yehoshua Yehuda Leib Diskin Rabbi Menahem Mendel ben Rabbi Shlomo Leib Brevda Rabbi Eliyahu Moshe Panigel Abraham Krochmal Rabbi Aryeh Leib Malin 17* | 4th of Sh’vat 18 | 5th of Sh’vat* 19 | 6th of Sh’vat* 20 | 7th of Sh’vat* 21 | 8th of Sh’vat* 22 | 9th of Sh’vat* 23* | 10th of Sh’vat* Parashat Bo Rabbi Yisrael Abuchatzeirah Rabbi Yehudah Aryeh Leib Alter Rabbi Chaim Tzvi Teitelbaum Rabbi Nathan David Rabinowitz -

Download Catalogue

F i n e J u d a i C a . printed booKs, manusCripts, Ceremonial obJeCts & GraphiC art K e s t e n b au m & C om pa n y thursday, nov ember 19th, 2015 K est e n bau m & C o m pa ny . Auctioneers of Rare Books, Manuscripts and Fine Art A Lot 61 Catalogue of F i n e J u d a i C a . BOOK S, MANUSCRIPTS, GR APHIC & CEREMONIAL A RT INCLUDING A SINGULAR COLLECTION OF EARLY PRINTED HEBREW BOOK S, BIBLICAL & R AbbINIC M ANUSCRIPTS (PART II) Sold by order of the Execution Office, District High Court, Tel Aviv ——— To be Offered for Sale by Auction, Thursday, 19th November, 2015 at 3:00 pm precisely ——— Viewing Beforehand: Sunday, 15th November - 12:00 pm - 6:00 pm Monday, 16th November - 10:00 am - 6:00 pm Tuesday, 17th November - 10:00 am - 6:00 pm Wednesday, 18th November - 10:00 am - 6:00 pm No Viewing on the Day of Sale This Sale may be referred to as: “Sempo” Sale Number Sixty Six Illustrated Catalogues: $38 (US) * $45 (Overseas) KestenbauM & CoMpAny Auctioneers of Rare Books, Manuscripts and Fine Art . 242 West 30th street, 12th Floor, new york, NY 10001 • tel: 212 366-1197 • Fax: 212 366-1368 e-mail: [email protected] • World Wide Web site: www.Kestenbaum.net K est e n bau m & C o m pa ny . Chairman: Daniel E. Kestenbaum Operations Manager: Jackie S. Insel Client Relations: Sandra E. Rapoport, Esq. Printed Books & Manuscripts: Rabbi Eliezer Katzman Rabbi Dovid Kamenetsky (Consultant) Ceremonial & Graphic Art: Abigail H. -

Tzadik Righteous One", Pl

Tzadik righteous one", pl. tzadikim [tsadi" , צדיק :Tzadik/Zadik/Sadiq [tsaˈdik] (Hebrew ,ṣadiqim) is a title in Judaism given to people considered righteous צדיקים [kimˈ such as Biblical figures and later spiritual masters. The root of the word ṣadiq, is ṣ-d- tzedek), which means "justice" or "righteousness". The feminine term for a צדק) q righteous person is tzadeikes/tzaddeket. Tzadik is also the root of the word tzedakah ('charity', literally 'righteousness'). The term tzadik "righteous", and its associated meanings, developed in Rabbinic thought from its Talmudic contrast with hasid ("pious" honorific), to its exploration in Ethical literature, and its esoteric spiritualisation in Kabbalah. Since the late 17th century, in Hasidic Judaism, the institution of the mystical tzadik as a divine channel assumed central importance, combining popularization of (hands- on) Jewish mysticism with social movement for the first time.[1] Adapting former Kabbalistic theosophical terminology, Hasidic thought internalised mystical Joseph interprets Pharaoh's Dream experience, emphasising deveikut attachment to its Rebbe leadership, who embody (Genesis 41:15–41). Of the Biblical and channel the Divine flow of blessing to the world.[2] figures in Judaism, Yosef is customarily called the Tzadik. Where the Patriarchs lived supernally as shepherds, the quality of righteousness contrasts most in Contents Joseph's holiness amidst foreign worldliness. In Kabbalah, Joseph Etymology embodies the Sephirah of Yesod, The nature of the Tzadik the lower descending