<1 August, 1965

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Image of the Cumans in Medieval Chronicles

Caroline Gurevich THE IMAGE OF THE CUMANS IN MEDIEVAL CHRONICLES: OLD RUSSIAN AND GEORGIAN SOURCES IN THE TWELFTH AND THIRTEENTH CENTURIES MA Thesis in Medieval Studies CEU eTD Collection Central European University Budapest May 2017 THE IMAGE OF THE CUMANS IN MEDIEVAL CHRONICLES: OLD RUSSIAN AND GEORGIAN SOURCES IN THE TWELFTH AND THIRTEENTH CENTURIES by Caroline Gurevich (Russia) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Medieval Studies. Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU. ____________________________________________ Chair, Examination Committee ____________________________________________ Thesis Supervisor ____________________________________________ Examiner ____________________________________________ CEU eTD Collection Examiner Budapest May 2017 THE IMAGE OF THE CUMANS IN MEDIEVAL CHRONICLES: OLD RUSSIAN AND GEORGIAN SOURCES IN THE TWELFTH AND THIRTEENTH CENTURIES by Caroline Gurevich (Russia) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Medieval Studies. Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU. ____________________________________________ External Reader CEU eTD Collection Budapest May 2017 THE IMAGE OF THE CUMANS IN MEDIEVAL CHRONICLES: OLD RUSSIAN AND GEORGIAN SOURCES IN THE TWELFTH AND THIRTEENTH CENTURIES by Caroline Gurevich (Russia) Thesis -

Voltaire's Conception of National and International Society

Voltaire's Conception of National and International Society LilIy Lo Manto Faced with the crumbling of their beloved Greek city-states, during the 4th century before our era, the Stoics used reason to explain their uncertain future in the huge global polis of the Macedonian empire. Two thousand years later, the economic, political and social turmoil brewing in France would foster the emergence of the French Enlightenment. Championed by the philosophes, this period would also look to reason to guide national and international security. Indeed, eighteenth century France was a society in ferment. After the death of Louis XIV, in 1715, the succeeding kings, Louis XV and XVI, found themselves periodically confronted, primarily by the pariements, with an increasing rejection of the absolutist claims and ministerial policies of the throne. l Like his Stoic forefathers, Fran~ois Marie Arouet (1694-1778), otherwise known as "Voltaire", extolled the merits of reason and tolerance,2 believing that the world would be a better place if men only behaved rationally.3 His primary focus was peace; how to obtain, preserve and propagate it. In order to comprehend Voltaire's conception of world peace, this essay will analyze what he believed to be its foundations, namely: the rights and roles of individuals based on their social class, and the role of an ideal state which would foster domestic harmony. According to Voltaire, the key to obtaining international peace stemmed from the relationship between the individual and the State. The relationship between the individual and the state, outlined in the Social Contract, could only succeed if man maintained his role and exercised his rights while the state assured him of his fundamental liberties. -

Testing the Elite: Yale College in the Revolutionary Era, 1740-1815

St. John's University St. John's Scholar Theses and Dissertations 2021 TESTING THE ELITE: YALE COLLEGE IN THE REVOLUTIONARY ERA, 1740-1815 David Andrew Wilock Saint John's University, Jamaica New York Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.stjohns.edu/theses_dissertations Recommended Citation Wilock, David Andrew, "TESTING THE ELITE: YALE COLLEGE IN THE REVOLUTIONARY ERA, 1740-1815" (2021). Theses and Dissertations. 255. https://scholar.stjohns.edu/theses_dissertations/255 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by St. John's Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of St. John's Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TESTING THE ELITE: YALE COLLEGE IN THE REVOLUTIONARY ERA, 1740- 1815 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY to the faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY of ST. JOHN’S COLLEGE OF LIBERAL ARTS AND SCIENCES at ST. JOHN’S UNIVERSITY New York by David A. Wilock Date Submitted ____________ Date Approved________ ____________ ________________ David Wilock Timothy Milford, Ph.D. © Copyright by David A. Wilock 2021 All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT TESTING THE ELITE: YALE COLLEGE IN THE REVOLUTIONARY ERA, 1740- 1815 David A. Wilock It is the goal of this dissertation to investigate the institution of Yale College and those who called it home during the Revolutionary Period in America. In so doing, it is hoped that this study will inform a much larger debate about the very nature of the American Revolution itself. The role of various rectors and presidents will be considered, as well as those who worked for the institution and those who studied there. -

Martin Luther—Translations of Two Prefaces on Islam

Word & World Volume XVI, Number 2 Spring 1996 Martin Luther—Translations of Two Prefaces on Islam: Preface to the Libellus de ritu et moribus Turcorum (1530), and Preface to Bibliander’s Edition of the Qur’an (1543) SARAH HENRICH and JAMES L. BOYCE Luther Seminary St. Paul, Minnesota I. INTRODUCTION:LUTHER ON “THE TURKS” N THE FIRST OF HIS WELL-KNOWN 95 THESES OF 1517, MARTIN LUTHER WROTE, I“When our Lord and Master, Jesus Christ, said ‘Repent,’ He called for the en- tire life of believers to be one of penitence.”1 Luther’s call for the centrality of re- pentance in the life of the Christian signals a key perspective in the theology of the reformer. To judge from his writings on the subject, that same key theological concern for Christian repentance shaped and characterized his attitude toward and understanding of the religion of Islam expressed throughout his career. For the encouragement of Christian repentance and prayer was Luther’s primary rationale for his actions to support and secure the publication of the 1543 edition 1Martin Luther: Selections From His Writings, ed. John Dillenberger (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1961) 490. Unless otherwise noted, all translations from the German and Latin in this article are by the authors. Citations from the works of Martin Luther are: WA = German Weimar Edition of Luthers works; LW = American Edition of Luthers works. JAMES BOYCE and SARAH HENRICH are professors of New Testament. Professor Boyce, a former editor of Word & World, has had varied service in the church and maintains an interest in philology and archaeology. -

Coversheet for Thesis in Sussex Research Online

A University of Sussex PhD thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details ‘Providence and Political Economy’: Josiah Tucker’s Providential Argument for Free Trade Peter Xavier Price PhD Thesis in Intellectual History University of Sussex April 2016 2 University of Sussex Peter Xavier Price Submitted for the award of a PhD in Intellectual History ‘Providence and Political Economy’: Josiah Tucker’s Providential Argument for Free Trade Thesis Summary Josiah Tucker, who was the Anglican Dean of Gloucester from 1758 until his death in 1799, is best known as a political pamphleteer, controversialist and political economist. Regularly called upon by Britain’s leading statesmen, and most significantly the Younger Pitt, to advise them on the best course of British economic development, in a large variety of writings he speculated on the consequences of North American independence for the global economy and for international relations; upon the complicated relations between small and large states; and on the related issue of whether low wage costs in poor countries might always erode the competitive advantage of richer nations, thereby establishing perpetual cycles of rise and decline. -

An Histokical Study of the Powers and Duties of the Peesidency in Yale College

1897.] The Prendency at Tale College. 27 AN HISTOKICAL STUDY OF THE POWERS AND DUTIES OF THE PEESIDENCY IN YALE COLLEGE. BY FRANKLIN B. DEXTER. Mr OBJECT in the present paper is to offer a Ijrief histori- cal vieAV of the development of the powers and functions of the presidential office in Yale College, and I desire at the outset to emphasize the statement that I limit myself strictl}' to the domain of historical fact, with no l)earing on current controA'ersies or on theoretical conditions. The corporate existence of the institution now known as Yale University dates from the month of October, 1701, when "A Collegiate School" Avas chartered b}^ the General Assembly of Connecticut. This action was in response to a petition then received, emanating primarily frojn certain Congregational pastors of the Colon}', who had been in frequent consnltation and had b\' a more or less formal act of giving books already taken the precaution to constitute themselves founders of the embiyo institution. Under this Act of Incorporation or Charter, seA'en of the ten Trustees named met a month later, determined on a location for tlie enterprise (at Sa3'brook), and among otlier necessary steps invited one of the eldest of their numl)er, the Reverend Abraham Pierson, a Harvard graduate, " under the title and cliaracter of Kector," to take the care of instrncting and ordering the Collegiate School. The title of "Collegiate School" was avowedly adopted from policy, as less pretentious than that to Avhich the usage at Harvard for sixty years had accustomed them, and tliere- 28 American Antiquarian Society. -

Journal of Family History

Journal of Family History http://jfh.sagepub.com "Tender Plants:" Quaker Farmers and Children in the Delaware Valley, 1681-1735 Barry Levy Journal of Family History 1978; 3; 116 DOI: 10.1177/036319907800300202 The online version of this article can be found at: http://jfh.sagepub.com Published by: http://www.sagepublications.com Additional services and information for Journal of Family History can be found at: Email Alerts: http://jfh.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://jfh.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Citations http://jfh.sagepub.com/cgi/content/refs/3/2/116 Downloaded from http://jfh.sagepub.com at MINNESOTA STATE UNIV MOORHEAD on February 17, 2010 116 "TENDER PLANTS:" QUAKER FARMERS AND CHILDREN IN THE DELAWARE VALLEY, 1681-1735 Barry Levy* &dquo;And whoso shall receive one such little child in my name, receiveth me. But whoso shall offend one of these little ones which believe in me, it were better for him that a millstone were hanged about his neck, and that he were drowned in the depth of the sea&dquo; (Matthew 18:5-6). I They directed intense attention to mar- In the late seventeenth and early eigh- riage and the conjugal household and in teenth centuries, the settlers of Chester spoke endlessly their Meetings about and the Welsh Tract, bordering Philadel- &dquo;tenderness&dquo; and &dquo;love.&dquo; These families, however, were not affectionate, phia, devoted themselves to their children, religious, or isolated. It was their and the results were economically impres- sentimental, relig- sive but socially ambiguous. -

Seventeenth-Century Scribal Culture and “A Dialogue Between King James and King William”

76 THE JOURNAL OF THE RUTGERS UNIVERSITY LIBRARIES SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY SCRIBAL CULTURE AND “A DIALOGUE BETWEEN KING JAMES AND KING WILLIAM” BY ERIN KELLY The latter portion of the seventeenth century saw the emergence of a number of institutions and practices whose existence we may take for granted in the modern era: the two-party parliamentary system pitted Whigs against Tories, the Royal Society formalized many aspects of empirical science, and the Stationers’ Company lost their monopoly over publication rights, effectively paving the way for modern copyright law. These changes emerged out of a tumultuous political context: England had been plunged into civil war in the middle of the century, and even the restoration of the monarchy did not entirely stifle those in parliament who opposed the monarch’s absolute power. The power struggle between the king and Parliament had a direct impact on England’s book industry: the first Cavalier Parliament of 1662 – only two years after the Restoration – revived the Licensing Act in an attempt to exercise power over what material was allowed to be printed. Through the act, the king could appoint a licenser to oversee the publication of books who could deny a license to any books thought to be objectionable.1 Roger L’Estrange, an arch-royalist, became Surveyor of the Presses, and later Licenser of the Press, and zealously exercised the power of these positions by hunting out unauthorized printing presses, suppressing seditious works, and censoring anti-monarchical texts.2 This was a dramatic change from the state of affairs prior to the Restoration, which had seen an explosion in the printing trade, when Parliament ostensibly exercised control over licensing, but did so through inconsistent laws and lax enforcement.3 The struggle between Parliament and the monarchy thus played itself out in part through a struggle for control over the censorship of the press. -

Extensions of Remarks E1521 EXTENSIONS of REMARKS

September 8, 2004 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks E1521 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS CITY OF SOUTHLAKE RANKED IN mother fell unconscious while on a shopping percent and helped save 1,026 lives. Blood TOP TEN trip. Bobby freed himself from the car seat and donors like Beth Groff truly give the gift of life. tried to help her. The young hero stayed calm, She has graciously donated 18 gallons of HON. MICHAEL C. BURGESS showed an employee where his grandmother blood. OF TEXAS was, and gave valuable information to the po- John D. Amos II and Luis A. Perez were lice. While on his way to school, Mike two residents of Northwest Indiana who sac- IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Spurlock came upon an accident scene. As- rificed their lives during Operation Iraqi Free- Tuesday, September 7, 2004 sisted by other heroic citizens, Mike broke out dom, and their deaths come as a difficult set- Mr. BURGESS. Mr. Speaker, it is my great one of the automobile’s windows and removed back to a community already shaken by the honor to recognize five communities within my the badly injured victim from the car. After the realities of war. These fallen soldiers will for- district for being acknowledged as among the incident, he continued on to school as usual to ever remain heroes in the eyes of this commu- ‘‘Top Ten Suburbs of the Dallas-Fort Worth take his final exam. nity, and this country. Area,’’ by D Magazine, a regional monthly The Red Cross is also recognizing the fol- I would like to also honor Trooper Scott A. -

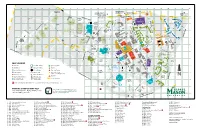

GMU-Fairfax-Campus-Map-2021.Pdf

A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z NO ENTRY NO EXIT EXIT NO Rapidan River Rd UNIVERSITY DRIVE TO: University Park Intramural Fields Mason Enterprise Center Commerce Building OX ROAD/ROUTE 123 TO: 4301 University Dr. 4087 University Dr. University Townhouse Complex 9 ROBERTS ROAD TO: 4260 Chain Bridge Rd. Tallwood 4210 Roberts Road R E V I KR C O N N A H A P P A 1 Student Townhouses 47 UNIVERSITY DRIVE UNIVERSITY DRIVE VE Reserved Parking GEORGE MASON BLVD S DR I PU M Field #1 LOT P A 35 C General Permit A Q 42 Parking U CO T S W OL I I D Rappahannock River A A S R H Parking Deck C C I 96 N L Spuhler Field L L LOT O R 38 L L D E 45 A A General Permit E 2 N O Mesocosm K R EVESHAM LANE E Parking Research BREDEN HILL LANE R L P ATRIOT CIRCLE Area A E PATRIOT CIRCLE N 39 V CHESAPEAKE RIVER LANE PERSHORE LANE I E R LOT M N Tennis CAMPUS DRIVE 23 97 Pilot A Softball General 63 62 Courts D House I Stadium Field House P Stadium Permit 98 D A Parking WEST CAMPUS WAY R LOT I Finley 61 3 Reserved Lot 69 OA Parking 34 S R 24 T Field #3 16 R Wotring 60 Courtyard 70 E OX ROAD/ROUTE 123 E B C A M P U S D R I V E L 56 C 65 STAFFORDSHIRE LANE R 20 I 71 51 49 RO C 21 BUFFALO CREEK CT T 58 72 4 O 33 Field #4 I 77 R 19 Maintenance T 64 WES T RAC A Storage Yard 6 Throwing CAMPUS DRIVE P 78 CA MPU S Fields Field 2 76 68 AY PA R K I N G 73 W LO T D 22 ROCKFISH CREEK LANE R 75 E Faculty/Staff Parking IV 74 R 53 66 8 57 SUB I NA Lot T N 5 5 31 E VA RIV 28 I CA US D AQUIA CREEK LANE R M P 67 Field #5 59 Y Kelly II A W NNA RI V E R 32 CAMPUS DRIVE A IV BRADDOCK ROAD/RT 620 PV LO T 10 R 27 KELLEY DRIVE General Parking 55 SHENANDOAH RIVER LANE 48 13 The Hub MASON POND DRVE 41 6 GLOBAL LANE RAC Mason Pond 25 Parking Deck BANISTER CREEK CT. -

Guide for International Students Why Choose George Mason University?

Guide for International Students Why Choose George Mason University? Make World-Changing Discoveries Tier 1 #14 1st Research Institute 1 of 81 Public Universities with Washington, DC, ranks #1 Carnegie Foundation's Tier 1 for the most STEM jobs in Highest Research Activity Most Innovative School a major US metro region (Carnegie Classification of Institutions of Higher Education) (U.S. News & World Report 2017) (AIER College Destinations Index 2016) #22 #12 Safest Campus Most Diverse University in the US in the United States (U.S. News & World Report 2018) (National Council for Home Safety and Security 2017) Ranked #22 45 minutes Nationwide for Top Internship Opportunities Outside of Washington, DC (The Princeton Review 2016) Employability at George Mason University Mason graduates are employed by many top companies, including: 84% 76% Boeing Lockheed Martin of employed students of Mason students are Volkswagen Accenture are in positions related employed within six Freddie Mac Marriott International to their career goals months of graduation Ernst & Young IBM (Mason Career Plans Survey 2016) (Mason Career Plans Survey 2016) 2 | INTO George Mason University 2018–2019 Top Programs GRADUATE #7 #17 #20 #27 Cybersecurity Special Education Criminology Systems Engineering (Ponemon Institute 2014) (U.S. News & World Report 2016) (U.S. News & World Report 2016) (U.S. News & World Report 2018) #33 #33 #64 #67 Economics Healthcare Public Policy Analysis Computer Science (U.S. News & World Report 2016) Management (U.S. News & World Report 2018) (U.S. News & World Report 2018) (U.S. News & World Report 2018) UNIVERSITY* #68 #78 #110 #140 Top Public Best Undergraduate Best Undergraduate in National Schools Business Programs Engineering Programs Universities *U.S. -

Natural Rights, Natural Religion, and the Origins of the Free Exercise Clause

ARTICLES REASON AND CONVICTION: NATURAL RIGHTS, NATURAL RELIGION, AND THE ORIGINS OF THE FREE EXERCISE CLAUSE Steven J. Heyman* ABSTRACT One of the most intense debates in contemporary America involves conflicts between religious liberty and other key values like civil rights. To shed light on such problems, courts and scholars often look to the historical background of the Free Exercise Clause of the First Amendment. But that inquiry turns out to be no less controversial. In recent years, a growing number of scholars have challenged the traditional account that focuses on the roles of Thomas Jefferson and James Madison in the movement to protect religious liberty in late eighteenth-century America. These scholars emphasize that most of the political energy behind the movement came from Evangelical Christians. On this revisionist account, we should not understand the Free Exercise Clause and corresponding state provisions in terms of the Enlightenment views of Jefferson and Madison, which these scholars characterize as secular, rationalist, and skeptical—if not hostile—toward religion. Instead, those protections were adopted for essentially religious reasons: to protect the liberty of individuals to respond to God’s will and to allow the church to carry out its mission to spread the Gospel. This Article offers a different understanding of the intellectual foundations of the Free Exercise Clause. The most basic view that supported religious liberty was neither secular rationalism nor Christian Evangelicalism but what contemporaries called natural religion. This view held that human beings were capable of using reason to discern the basic principles of religion, including the duties they owed to God and one another.