Potential Use of Telephone-Based Survey for Non-Communicable Disease Surveillance in Sri Lanka H

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RP: Sri Lanka: Hikkaduwa-Baddegama Section Of

Resettlement Plan May 2011 Document Stage: Draft SRI: Additional Financing for National Highway Sector Project Hikkaduwa–Baddegama Section of Hikkaduwa–Baddegama–Nilhena Road (B153) Prepared by Road Development Authority for the Asian Development Bank. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 11 May 2011) Currency unit – Sri Lanka rupee (Rs) Rs1.00 = $0.009113278 $1.00 = Rs109.730000 ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank CEA – Central Environmental Authority CSC – Chief Engineer’s Office CSC – Construction Supervision Consultant CV – Chief Valuer DSD – Divisional Secretariat Division DS – Divisional Secretary ESD – Environment and Social Division GN – Grama Niladhari GND – Grama Niladhari Division GOSL – Government of Sri Lanka GRC – Grievance Redress Committee IOL – inventory of losses LAA – Land Acquisition Act LARC – Land Acquisition and Resettlement Committee LARD – Land Acquisition and Resettlement Division LAO – Land Acquisition Officer LARS – land acquisition and resettlement survey MOLLD – Ministry of Land and Land Development NEA – National Environmental Act NGO – nongovernmental organization NIRP – National Involuntary Resettlement Policy PD – project director PMU – project management unit RP – resettlement plan RDA – Road Development Authority ROW – right-of-way SD – Survey Department SES – socioeconomic survey SEW – Southern Expressway STDP – Southern Transport Development Project TOR – terms of reference WEIGHTS AND MEASURES Ha hectare km – kilometer sq. ft. – square feet sq. m – square meter NOTE In this report, "$" refers to US dollars. This resettlement plan is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. -

Registered Suppliers and Contractors for the Year- 2021 District Secretariat-Galle

Registered Suppliers And Contractors 2021 2 District Secretariat - Galle Content Subject Page No. Stationery and office requisites (Computer Papers, Roneo Papers, CD, Printer Toner, Printer Ribbon, Photocopy 01. 01 Cartridge including Fax Roll) ..…………….............……………………………………………………………….……… Office Equipments (Printers, Photocopy Machines, Roneo Machines, Digital Duplo Machines, Fax Machines) 02. 04 ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..…….………….. 03. Office Furniture (Wooden, Steel and Plastic) …………………………………….......................................................... 06 04. Computers and Computer Accessories and Networking Devices ……………………….……………………….…………… 08 05. Domestic Electrical Equipment (Televisions,Sewing Machines,Refrigerators,Washing Machines etc.) ……..… 10 06. Generators ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..…………… 12 07. Rubber Stamps ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..…………… 13 08. Textile Materials for doors and windows,bed clothes,uniforms ………………………………………………..………….. 14 09. Beauty Culture Equipments ….…...……………………………………………………………………………………………..…………… 15 10. Office Bags ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..…………. 16 11. School Equipments (Bags,Shoes, etc..) ……………………………………………………………………………………….…………… 17 12. Sports Goods and Body Building Equipment ……………………………………………………………………………….……………... 18 13. Musical Instruments …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….………….. 19 14. Tyres,Tubes, and Batteries for vehicles …………………………………………………………………………………………….……….. 20 15. Vehicle Spare Parts ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….………… -

GN Divisions with Crown Lands DS: Bentota

DISTRICT : Galle GN Divisions with Crown Lands DS: Bentota Area Detail Previous Revised GN Division Code* GN P-Code Akadegoda 10B 3103155 Dedduwa 6 3103055 Delkabalagoda 40E 3103250 Dope 5 3103030 Elakaka 12E 3103105 Etawalawatta East 9A 3103145 Etawalawatta West 9B 3103140 Ethungagoda 14E 3103110 Yasthramulla 3103015 Galthuduwa 11B 3103175 Pahurumulla Haburugala 12 3103085 3103005 Kommala Hipanwatta 40B 3103255 Legend 3103020 KALUTARA DISTRICT Ihala Malawela 40D 3103230 Sinharoopagama Kahawegammedda 10 3103160 Bentota GN Division 3103010 Bodhimaluwa Kaikawala 9 3103130 3103025 Crown Lands Kandemulla 10C 3103170 Huganthota Wadumulla Kolaniya 11E 3103180 DS Boundary Angagoda 3103050 3103035 Dope Kommala 3C 3103020 3103030 Kotuwabendahena 40A 3103235 District Boundary Kahagalla 3103045 Kuda Uragaha 40C 3103240 Maha Uragaha 40 3103245 Thunduwa East 3103095 Mahagoda 14 3103195 Haburugala Thunduwa West Mahavila East 14B 3103210 Warahena Dedduwa 3103085 3103090 3103040 3103055 Mahavila West 14C 3103205 Thotakanatta Malawela 13B 3103225 3103100 Miriswatta 14A 3103185 Title: GN Divisions with Crown Lands Elakaka Olaganduwa 8B 3103120 Sub Title: Bentota DS Division, Galle District 3103105 Pilekumbura 14D 3103200 Sooriyagama Moragoda Sinharoopagama 3B 3103010 Data source(s): Athuruwella 3103080 3103215 3103060 Viyandoowa Sooriyagama 12D 3103080 Divisisional Secretariat, Bentota. 3103190 Thotakanatta 12A 3103100 Ethungagoda Mahagoda Viyandoowa 12F 3103190 Galbada Mullegoda 3103110 3103195 3103065 3103075 Bentota Warakamulla 10A 3103165 Galagama -

Sinhalese Buddhist Nationalist Ideology: Implications for Politics and Conflict Resolution in Sri Lanka

Policy Studies 40 Sinhalese Buddhist Nationalist Ideology: Implications for Politics and Conflict Resolution in Sri Lanka Neil DeVotta East-West Center Washington East-West Center The East-West Center is an internationally recognized education and research organization established by the U.S. Congress in 1960 to strengthen understanding and relations between the United States and the countries of the Asia Pacific. Through its programs of cooperative study, training, seminars, and research, the Center works to promote a stable, peaceful, and prosperous Asia Pacific community in which the United States is a leading and valued partner. Funding for the Center comes from the U.S. government, private foundations, individuals, cor- porations, and a number of Asia Pacific governments. East-West Center Washington Established on September 1, 2001, the primary function of the East- West Center Washington is to further the East-West Center mission and the institutional objective of building a peaceful and prosperous Asia Pacific community through substantive programming activities focused on the themes of conflict reduction, political change in the direction of open, accountable, and participatory politics, and American under- standing of and engagement in Asia Pacific affairs. Sinhalese Buddhist Nationalist Ideology: Implications for Politics and Conflict Resolution in Sri Lanka Policy Studies 40 ___________ Sinhalese Buddhist Nationalist Ideology: Implications for Politics and Conflict Resolution in Sri Lanka ___________________________ Neil DeVotta Copyright © 2007 by the East-West Center Washington Sinhalese Buddhist Nationalist Ideology: Implications for Politics and Conflict Resolution in Sri Lanka By Neil DeVotta ISBN: 978-1-932728-65-1 (online version) ISSN: 1547-1330 (online version) Online at: www.eastwestcenterwashington.org/publications East-West Center Washington 1819 L Street, NW, Suite 200 Washington, D.C. -

Table 1.Xlsx

Census of Population and Housing of Sri Lanka, 2012 Table 1: Population by divisional secretariat division,sex and sector All sectors Urban Sector Rural Sector Estate Sector Divisional secretariat division Both Both Both Both sexes Male Female Male Female Male Female Male Female sexes sexes sexes Galle District 1,063,334 509,902 553,432 133,398 63,778 69,620 911,159 437,019 474,140 18,777 9,105 9,672 Benthota 49,975 24,084 25,891 ‐ ‐ ‐ 49,975 24,084 25,891 ‐ ‐ ‐ Balapitiya 67,432 31,977 35,455 ‐ ‐ ‐ 67,432 31,977 35,455 ‐ ‐ ‐ Karandeniya 62,498 30,175 32,323 ‐ ‐ ‐ 62,498 30,175 32,323 ‐ ‐ ‐ Elpitiya 64,726 31,068 33,658 ‐ ‐ ‐ 62,840 30,194 32,646 1,886 874 1,012 Niyagama 35,574 17,279 18,295 ‐ ‐ ‐ 35,574 17,279 18,295 ‐ ‐ ‐ Thawalama 32,609 15,957 16,652 ‐ ‐ ‐ 31,917 15,614 16,303 692 343 349 Neluwa 28,640 14,394 14,246 ‐ ‐ ‐ 27,834 13,974 13,860 806 420 386 Nagoda 53,829 25,936 27,893 ‐ ‐ ‐ 47,746 22,979 24,767 6,083 2,957 3,126 Baddegama 75,008 35,757 39,251 ‐ ‐ ‐ 72,788 34,656 38,132 2,220 1,101 1,119 Welivitiya‐Ddivithura 29,347 13,988 15,359 ‐ ‐ ‐ 27,903 13,287 14,616 1,444 701 743 Ambalangoda 56,961 27,302 29,659 19,990 9,434 10,556 36,971 17,868 19,103 ‐ ‐ ‐ Gonapeenuwala 21,755 10,261 11,494 ‐ ‐ ‐ 21,755 10,261 11,494 ‐ ‐ ‐ Hikkaduwa 101,909 49,104 52,805 27,075 12,920 14,155 74,834 36,184 38,650 ‐ ‐ ‐ Galle Four Gravets 101,749 48,796 52,953 86,333 41,424 44,909 15,416 7,372 8,044 ‐ ‐ ‐ Bope‐Poddala 50,331 23,863 26,468 ‐ ‐ ‐ 50,052 23,730 26,322 279 133 146 Akmeemana 77,776 36,906 40,870 ‐ ‐ ‐ 75,777 35,940 39,837 1,999 966 -

1 Imaduwa Pradeshiya Sabha

P.S.No. 2014/289 Sixth Instalment – Part -XXI Local Authorities - Galle District Report of the Auditor General 2011 Imaduwa Pradeshiya Sabha ------------------------------------------- Galle District --------------------- 1. Financial Statements -------------------------- 1.1 Presentation of Financial Statements -------------------------------------------- The financial statements for the year under review had been presented to audit on 30 March 2012 and the financial statements for the preceding year had been presented on 30 March 2011. The report of the Auditor general for the year under review was issued to the Chairman of the Sabha on 30 October 2012. 1:2 Opinion ---------- So far as appears from my examination and to the best of information and according to the explanations given to me, I am of opinion that the Imaduwa Pradeshiya Sabha had maintained proper accounting records for the year ended 31 December 2011 and except for the effects on the financial statements of the matters referred to in my report, the financial statements have been prepared in accordance with the Generally Accepted Accounting Principles and give a true and fair view of the state of affairs of the Imaduwa Pradeshiya Sabha as at 31 December 2011 and the financial results of its operations and cash flows for the year then ended. 1.3 Comments on Financial Statements --------------------------------------------- 1.3.1 Accounting Deficiencies ---------------------------------- The Assets and Liabilities Distribution committee had recommended that the Habarduwa Pradeshiya Sabha should vest assets amounting to Rs.9,794,393 and liabilities amounting to Rs. 2,051,704 with the Imaduwa Pradeshiya Sabha. Although the accounts had been prepared based on the above assets and liabilities, they had not been legally acquired by the Pradeshiya Sabha even by 27 June 2012. -

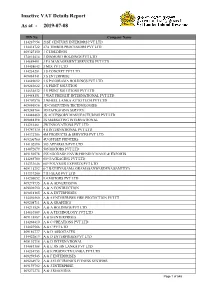

Inactive VAT Details Report As at - 2019-07-08

Inactive VAT Details Report As at - 2019-07-08 TIN No Company Name 114287954 21ST CENTURY INTERIORS PVT LTD 114418722 27A TIMBER PROCESSORS PVT LTD 409327150 3 C HOLDINGS 174814414 3 DIAMOND HOLDINGS PVT LTD 114689491 3 FA MANAGEMENT SERVICES PVT LTD 114458643 3 MIX PVT LTD 114234281 3 S CONCEPT PVT LTD 409084141 3 S ENTERPRISE 114689092 3 S PANORAMA HOLDINGS PVT LTD 409243622 3 S PRINT SOLUTION 114634832 3 S PRINT SOLUTIONS PVT LTD 114488151 3 WAY FREIGHT INTERNATIONAL PVT LTD 114707570 3 WHEEL LANKA AUTO TECH PVT LTD 409086896 3D COMPUTING TECHNOLOGIES 409248764 3D PACKAGING SERVICE 114448460 3S ACCESSORY MANUFACTURING PVT LTD 409088198 3S MARKETING INTERNATIONAL 114251461 3W INNOVATIONS PVT LTD 114747130 4 S INTERNATIONAL PVT LTD 114372706 4M PRODUCTS & SERVICES PVT LTD 409206760 4U OFFSET PRINTERS 114102890 505 APPAREL'S PVT LTD 114072079 505 MOTORS PVT LTD 409150578 555 EGODAGE ENVIR;FRENDLY MANU;& EXPORTS 114265780 609 PACKAGING PVT LTD 114333646 609 POLYMER EXPORTS PVT LTD 409115292 6-7 BATHIYAGAMA GRAMASANWARDENA SAMITIYA 114337200 7TH GEAR PVT LTD 114205052 9.4.MOTORS PVT LTD 409274935 A & A ADVERTISING 409096590 A & A CONTRUCTION 409018165 A & A ENTERPRISES 114456560 A & A ENTERPRISES FIRE PROTECTION PVT LT 409208711 A & A GRAPHICS 114211524 A & A HOLDINGS PVT LTD 114610569 A & A TECHNOLOGY PVT LTD 409118887 A & B ENTERPRISES 114268410 A & C CREATIONS PVT LTD 114023566 A & C PVT LTD 409186777 A & D ASSOCIATES 114422819 A & D ENTERPRISES PVT LTD 409192718 A & D INTERNATIONAL 114081388 A & E JIN JIN LANKA PVT LTD 114234753 A & -

Tourist Accommodation

Tourist Accommodation Number of SLTDA Registered Accommodation Establishments as at end March 2019 Classified Tourist Hotels Number of Number of Categorization 6% Establishments Rooms Unclassified Classified Tourist Others 41% Hotels Hotels 147 13,544 10% Five star 23 5,150 Four Star 23 2,438 Three Star 24 2,416 Boutique Guest Hotel and Houses Two Star 39 1,878 Villa 40% One Star 38 1,662 3% Tourist Hotel [Cite your source here.] (Unclassified) 242 10,446 Boutique Hotel 32 638 Tourist… 10,446 Boutique Villa 40 265 Rented Home 19 Rented Apartment 223 Guest House 969 10,594 Hostels 16 Bungalow 412 1,701 Home Stay Unit 1,434 Heritage Bungalow 4 19 Heritage Home 9 Heritage Home 3 9 Heritage Bungalow 19 Guest House 10,594 Home Stay Unit 476 1,434 Classified Tourist… 13,544 Hostels 2 16 Bungalow 1,701 Rented Apartment 70 223 Boutique Villa 265 Rented Home 6 19 Boutique Hotel 638 0 5,000 10,000 15,000 Number of Rooms Total 2,403 38,908 [Cite your source here.] The total number of SLTDA registered accommodation establishments as at 31st March 2019 was 2,403. The number of classified tourist Hotels was 147 and among them 23 were five-star hotels. The presence of small and medium enterprises is strong with guest houses, homestays and bungalows recording the highest number of registered establishments with 969, 476 and 412 respectively. The total room inventory was 38, 908. Classified tourist hotels (1-5 star) had the highest inventory of 13, 544 rooms. Geographical Distribution of Rooms of SLTDA Registered Tourist Establishments Number of Rooms Distribution (NRD) NRD > 7,000 7,000 > NRD > 5,000 5,000 > NRD > 3,000 3,000 > NRD > 1000 1,000 > NRD > 500 500 > NRD > 0 [Cite your source here.] [Cite your source here.] The map depicts the distribution of rooms in SLTDA registered tourist establishments within each district. -

Map of Sri Lanka

MINISTRY OF HEALTH, NUTRITION & WELFARE, THE DEMOCRATIC SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF SRI LANKA (MOH) JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY (JICA) MASTER PLAN STUDY FOR STRENGTHENING HEALTH SYSTEM IN THE DEMOCRATIC SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF SRI LANKA SUPPORTING DOCUMENT III MAPS HEALTHY & SHINING ISLAND IN THE 21ST CENTURY FINAL REPORT NOVEMBER 2003 PACIFIC CONSULTANTS INTERNATIONAL The following foreign exchange rate is applied in the study: US$ 1.00 = 95 Sri Lanka Rupees (as of November 2003) November 2003 Mr. Kazuhisa MATSUOKA Vice President Japan International Cooperation Agency Tokyo, Japan Message from Vice President, Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) Letter of Transmittal Dear Sir, We are pleased to formally submit herewith the Final Report of “The Master Plan Study In response to a request from the Government of the Democratic Socialist Republic of for Strengthening Health System in the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka.” Sri Lanka, the Government of Japan decided to provide technical cooperation for This report compiles the results of the Study which was conducted from March 2002 establishing of a health master plan which will be effective for the next decade for the through November 2003 by the Study Team organized by Pacific Consultants improvement of the health system in Sri Lanka. JICA selected and dispatched the International under the contract with JICA. study team headed by Dr. Katsuhide Nagayama of Pacific Consultants International to The report compiles the Sri Lanka Health Master Plan covering both reform and Sri Lanka between March 2002 and November 2003. development of the health sector in Sri Lanka. The plan consists of 1) vision, goals and objectives; 2) overall basic strategies; 3) frameworks for health sector reform and I am pleased that the Health Master Plan, presented herewith by Ministry of Health, development; and 4) priority programmes. -

Details of Designated Officer and Information Officers

Details of Designated Officer and Information Officers Name of the Designated Telephone institution/Departme Officer/Informa Name of the Officer Office Address Fax / E-mail Number nt/ Office tion Officer Commissioner General of Elections/ Mr.M.K. Saman Sri Election Commission Designated Officer Director General of Elections, Election 0112885207 0112885208 Rathnayake Commission, Sarana Mawatha, Rajagiriya. Additional Commissioner of Elections Election Commission Information Officer Mr. H.R.P. Pieris (Legal and Investigation), Election 0112868448 0112868448 Commission, Sarana Mawatha, Rajagiriya. Galle District Election Deputy Commissioner of Elections, Information Officer Mr. K.U. Chandralal 0912234028 0912234028 Office District Election Office, Galle. Matara District Election Assistant Commissioner of Elections, Information Officer Miss. T.W.P Kaumadi 0412222305 0412222305 Office District Election Office, Matara Kalutara District Election Mr. W.W.K. Jayaweera Deputy Commissioner of Elections, Information Officer 0342222266 0342222266 Office Fernando District Election Office, Kalutara. Kandy District Election Deputy Commissioner of Elections, Information Officer Mr. T.A.C.N. Thalangama 0812233187 0812233190 Office District Election Office, Kandy. Deputy Commissioner of Elections, Colombo City Election Colombo City Election Office, 05th Information Officer Mr. P.A.S. Senaratne 0112369437 0112369279 Office Floor, Nila Medura, Elvitigala Mawatha, Narahenpita, Colombo 05. Assistant Commissioner of Elections, Colombo District Colombo City Election Office, 05th Information Officer Mr. S.D.S.A. Rupasinghe 0112369438 0112369481 Election Office Floor, Nila Medura, Elvitigala Mawatha, Narahenpita, Colombo 05. Gampaha District Deputy Commissioner of Elections, Information Officer Mr. K.J.S. Madhawa 0332222047 0332222047 Election Office District Election Office, Gampaha. Gampaha (North) Assistant Commissioner of Elections, Information Officer Mr. B.M.I.S.I. Bandara 0332222743 0332222743 Election Office District Election Office, Gampaha. -

Development Plan for Greater Galle Area 2019 - 2030

DEVELOPMENT PLAN FOR GREATER GALLE AREA 2019 - 2030 Part I Urban Development Authority District office - Galle I Minister’s forward ii Local Authority Chairman’s Foreword iii Preface Cities are changing; therefore, the emerging trends of development requires to find innovative solutions to meet the changes well. The Urban Development itself also means responsibility for future generations through innovations. Galle as one of the rapidly growing cities in the region as well as in Sri Lanka, the spatial structure of the city also being subjected to changes over the time by expanding the growth towards outer city. This scenario has made significant changes in the city structure and the development. Therefore, in this context, Greater Galle Development Plan will be an instrument that offers visionary, intelligent solutions for the future-oriented development of Greater Galle to the questions arise today and that will arise in the future. The plan was developed as a part of broad discussion process among policymakers, administrators, the scientific and business communities, residents and special interest groups. Since the aim of the development plan was to create a city for the people and where they want to live, not where they live because they have to. iv Acknowledgement Its’s a great privilege to express the feeling of our gratitude for the people who were backing the success in preparing the Greater Galle Development Plan 2019-2030. First and foremost, we would like to thank the Mayor and the commissioner of Galle Municipal Council and chairmen and the secretaries of Bope-Poddala, Akmeemana and Habaraduwa Pradeshiya Sabhas along with the members of the staff for extending their extreme support to successfully complete the Greater Galle Development Plan 2030. -

Galle District 25 – 31 July 2005

No.4 WEEKLY HUMANITARIAN OVERVIEW – GALLE DISTRICT 25 – 31 JULY 2005 HIGHLIGHTS On Thursday, July 28 the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) co-chaired the first Fisheries, Agriculture and Livestock meeting with the Department of Fisheries, Department of Agriculture and Livestock in Galle District. Following the coordination meeting FAO distributed fishing gear and nets kindly donated by the Japanese Government as official development assistance. The National Housing Development Authority (NHDA) is building a prototype of a house made out of clay planned as part of a housing scheme for the poor population, some of who are tsunami affected families. A return of foreign and domestic tourists in Galle District has seen beach coastline areas such as Unawatuna and Hikkaduwa filled with holidaymakers bringing in business for local hoteliers, restaurants and cafes owners, and handicraft and beachwear vendors. HOUSING AND SHELTER alternative solution for good quality cheap housing. NHDA plan to implement this housing scheme in The National Housing Development Authority (NHDA) several electorates, and was particularly interested in is developing a new method to construct housing finding methods to be more friendly and conscious of units at minimum cost using clay as the primary environmental aspects. building material. A prototype is being built in the village of Katuruduwa, Akmeemana, about 5km inland from Galle Town, as a sample unit to show to beneficiaries and other potential homeowners its worthy and efficient methods. These houses are targeted to accommodate for the population below the poverty line, in particular those who were affected by the tsunami but have no eligibility to the provision of a permanent house.