“Invent and Subvert: Paula Rego's Illustrations for Children's Books”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Making of Paula Rego's 'The Nursery Rhymes'

The making of Paula Rego’s ‘The Nursery Rhymes’ Abstract This article looks at the series of etchings and aquatints entitled The Nursery Rhymes that Paula Rego made in 1989 in collaboration with printer Professor Paul Coldwell. Whilst she had already had some printmaking experience, The Nursery Rhymes constituted her first major engagement with printmaking. The article considers the circumstances under which the prints were made, both in terms of her personal circumstances and her professional standing, and examines their reception and continuing popularity. It also gives personal insights and commentary on the series, looking at both her iconography and her connection to a wide range of graphic work. It does so from the author’s unique perspective as the printer and collaborator in the project and offers insights into the working relationship between artist and printer. The making of Paula Rego’s ‘The Nursery Rhymes’ Paul Coldwell Paula Rego has always identified with the least, not the mighty, taken the child’s eye view, and counted herself among the commonplace and the disregarded, by the side of the beast, not the beauty… Her sympathy with naiveté, her love of its double character, its weakness and its force, has led her to Nursery Rhymes as a new source for her imagery. (Warner 1989) Paula Rego was born in Lisbon in 1935 and attended the Slade School of Art in London between 1952–56 where she met her husband, the painter Victor Willing. In 1957 she returned to live in Portugal with her three children, living between London and Portugal for a few years before finally settling in London in 1976. -

Material Culture, New Corpographies of the Feminine and Narratives of Dissent: Myra, by Maria Velho Da Costa and Paula Rego: An

Material culture, new corpographies of the feminine and narratives of dissent: Myra, by Maria Velho da Costa and Paula Rego: an intersemiotic dialogue Autor(es): Macedo, Ana Gabriela Publicado por: Imprensa da Universidade de Coimbra URL persistente: URI:http://hdl.handle.net/10316.2/42349 DOI: DOI:https://doi.org./10.14195/978-989-26-1308-6_37 Accessed : 13-Nov-2017 15:45:03 A navegação consulta e descarregamento dos títulos inseridos nas Bibliotecas Digitais UC Digitalis, UC Pombalina e UC Impactum, pressupõem a aceitação plena e sem reservas dos Termos e Condições de Uso destas Bibliotecas Digitais, disponíveis em https://digitalis.uc.pt/pt-pt/termos. Conforme exposto nos referidos Termos e Condições de Uso, o descarregamento de títulos de acesso restrito requer uma licença válida de autorização devendo o utilizador aceder ao(s) documento(s) a partir de um endereço de IP da instituição detentora da supramencionada licença. Ao utilizador é apenas permitido o descarregamento para uso pessoal, pelo que o emprego do(s) título(s) descarregado(s) para outro fim, designadamente comercial, carece de autorização do respetivo autor ou editor da obra. Na medida em que todas as obras da UC Digitalis se encontram protegidas pelo Código do Direito de Autor e Direitos Conexos e demais legislação aplicável, toda a cópia, parcial ou total, deste documento, nos casos em que é legalmente admitida, deverá conter ou fazer-se acompanhar por este aviso. pombalina.uc.pt digitalis.uc.pt IMPRENSA DA UNIVERSIDADE DE COIMBRA COIMBRA UNIVERSITY PRESS II HOMENAGEM A IRENE RAMALHO SANTOS THE EDGE OF ONE OF MANY CIRCLES ISABEL CALDEIRA GRAÇA CAPINHA JACINTA MATOS ORGANIZAÇÃO M ateRial CUltURE, neW coRPOGRAPHies of THE feMinine and naRRatives of dissent. -

Annual Report 2019/2020 Contents II President’S Foreword

Annual Report 2019/2020 Contents II President’s Foreword IV Secretary and Chief Executive’s Introduction VI Key figures IX pp. 1–63 Annual Report and Consolidated Financial Statements for the year ended 31 August 2020 XI Appendices Royal Academy of Arts Burlington House, Piccadilly, London, W1J 0BD Telephone 020 7300 8000 royalacademy.org.uk The Royal Academy of Arts is a registered charity under Registered Charity Number 1125383 Registered as a company limited by a guarantee in England and Wales under Company Number 6298947 Registered Office: Burlington House, Piccadilly, London, W1J 0BD © Royal Academy of Arts, 2020 Covering the period Portrait of Rebecca Salter PRA. Photo © Jooney Woodward. 1 September 2019 – Portrait of Axel Rüger. Photo © Cat Garcia. 31 August 2020 Contents I President’s I was so honoured to be elected as the Academy’s 27th President by my fellow Foreword Academicians in December 2019. It was a joyous occasion made even more special with the generous support of our wonderful staff, our loyal Friends, Patrons and sponsors. I wanted to take this moment to thank you all once again for your incredibly warm welcome. Of course, this has also been one of the most challenging years that the Royal Academy has ever faced, and none of us could have foreseen the events of the following months on that day in December when all of the Academicians came together for their Election Assembly. I never imagined that within months of being elected, I would be responsible for the temporary closure of the Academy on 17 March 2020 due to the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. -

Modern British and Irish Art Montpelier Street, London | 16 September 2020

Modern British and Irish Art Montpelier Street, London | 16 September 2020 Modern British and Irish Art Montpelier Street, London | Wednesday 16 September 2020, at 1pm BONHAMS BIDS ENQUIRIES IMPORTANT INFORMATION Montpelier Street +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 Janet Hardie The United States Government Knightsbridge +44 (0) 20 7447 7401 fax Specialist has banned the import of ivory into London SW7 1HH [email protected] +44 (0) 20 7393 3949 the USA. Lots containing ivory are www.bonhams.com [email protected] indicated by the symbol Ф printed To bid via the internet please beside the lot number in this visit www.bonhams.com Catherine White catalogue. VIEWING Junior Cataloguer Sunday 13 September Please note that bids should be +44 (0) 20 7393 3884 REGISTRATION 11am -3pm submitted no later than 4pm [email protected] IMPORTANT NOTICE Monday 14 September on the day prior to the auction. Please note that all customers, 9am- 4.30pm New bidders must also provide PRESS ENQUIRIES irrespective of any previous activity Tuesday 15 September proof of identity when submitting [email protected] with Bonhams, are required to 9am-4.30pm bids. Failure to do this may result complete the Bidder Registration Wednesday 16 September in your bids not being processed. Form in advance of the sale. The CUSTOMER SERVICES 9am - 11am form can be found at the back of Bidding by telephone will only be Monday to Friday every catalogue and on our website Viewing is by timed appointment accepted on a lot with the lower 8.30am – 6pm at www.bonhams.com and should only, please contact Catherine estimate in excess of £500. -

Casa Das Histórias Paula Rego: Building and Collection: a Dual Challenge

Casa das Histórias Paula Rego: Building and Collection: a Dual Challenge Catarina Alfaro Chief Curator at Casa das Histórias Paula Rego Abstract An example of synthesis space between art and architecture, Casa das Histórias Paula Rego emerged in Portuguese museological reality in September 2009. Since then this museum has been recognised at national and international level as one of the most significant for understanding the artist's work. The result of an illustrious meeting between two artists, Paula Rego and Eduardo Souto de Moura, the museum presents itself as an interesting case study to analyze the relationships and the challenges posed by a collection and its link to the plasticity of the building-architectural object. Key words: Monographic Museum Collection Exhibition Conservation Museological programming Introduction New contemporary art museums as emblematic aspects of attempts to decentralise cultural policies The Casa das Histórias Paula Rego emerged on the Portuguese museum scene in September 2009, fitting into a process of decentralisation of cultural policy that occurred quite visibly in Portugal. Making use of Nuno Grande’s reflection (2004) on this subject to generically explain the process, in the recent past, and despite the growth of some “decentralisation” networks, the history of cultural policies in Portugal is mirrored in the history of its “architectures of culture.” Recourse to the star-system of Portuguese architecture ensures the iconic status of these cultural projects as “signed” works, desired by various cities. Institutions such as the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation Museum, the Modern Art Centre, the Centro Cultural de Belém and the Serralves Foundation Contemporary Art Museum have marked relevant socio-political changes in Portugal, giving predominance to Portuguese and foreign artistic production, putting our main cities on international cultural circuits. -

Marion Coutts

Marion Coutts www.marioncoutts.com books 2014 The Iceberg, Winner of the Wellcome Book Prize 2015 Published by Atlantic Books 2014, hardback 294 pp. ISBN 978-1782393504, paperback ISBN 978-17823934528 Shortlisted for the Samuel Johnson Prize for non-fiction 2014; the Costa Biography Award 2015; the Pol Roger Duff Cooper Award 2015. Longlisted for the Guardian First Book Award 2014 Finalist in the National Book Critics Circle Awards of America 2017 Mandarin edition 2015: Spanish edition 2016: US edition 2016: Audible Audiobook 2016: simplified Chinese edition 2017 2012 English Graphic, Tom Lubbock Edited by Marion Coutts with an introduction by Jamie McKendrick. Published by Frances Lincoln, October 2012. Hardback. 208 pp. ISBN 978-0-71123-370-6 Until Further Notice, I am Alive, Tom Lubbock: Introduction by Marion Coutts co-edited by Marion Coutts and Bella Lacey. Published by Granta, April 2012. Hardback. 160pp. ISBN 978-1-84708-531-3 links Andrew Solomon, NY Times: http://www.nytimes.com/2016/02/14/books/review/the-good-death-when-breath-becomes-air-and-more.html?_r=0 Little Atoms podcast: http://littleatoms.com/podcast/wellcome-book-prize-special-henry-marsh-and-marion-coutts 5x15 podcast: http://5x15stories.com/presenter/marion-coutts/ selected solo exhibitions 2017 Tintype, London 2008 Twenty Six Things Wellcome Collection, London 2007 New Art Centre, Roche Court, Wiltshire 2005 Money Tablet, London Mountain Kettle’s Yard, Cambridge 2004 Everglade 2 Princelet Street, London Angel Row Gallery, Nottingham 2003 Kettle’s Yard, Cambridge -

Paula Rego-Printmaker by Professor Paul Coldwell © the Dreams

Paula Rego-Printmaker By Professor Paul Coldwell © The dreams, however could not help me over my feeling of disorientation. On the contrary, I had lived as if under constant inner pressure. At times this became so strong that I suspected there was some psychic disturbance in myself. Therefore I twice went over all the details of my entire life, with particular attention to childhood memories; for I thought there might be something in my past, which I could not see and which might possibly be the cause of the disturbance. But this retrospection led to nothing but a fresh acknowledgement of my own ignorance. Thereupon I said to myself, "Since I know nothing at all, I shall simply do whatever occurs to me." Thus I consciously submitted myself to the impulses of the unconscious. Memories, Dreams, Reflections. C.G.Jung Paula Rego is one of the most celebrated and , I would suggest, problematic artists currently working in Britain. She has continually renewed her practice, which has included the cut, paste and painted collages of the 1950s and 60s, the animal pictures of the 80s which developed into the more grounded grand compositions, the large pastels through to the present obsessive fixation with working directly from the observed experience, in order to delve into her imagination. While many contemporary artists, especially women, have embraced new media and processes to discover a personal visual language, Rego has steadfastly engaged herself within the complexities of traditional practice, seeking to take on the challenge of painting. Parallel to this, she has produced a profound body of work as a printmaker, the subject of this retrospective, in which once again she works within established modes of practice, in her case predominantly intaglio and more recently lithography. -

Victoria Miro Announces Representation of Paula Rego

Victoria Miro announces representation of Paula Rego Paula Rego in her studio Photo: © Nick Willing 2020 Victoria Miro is delighted to announce the representation of Paula Rego. This new collaboration with the artist will be marked by a major exhibition at the gallery during the latter part of 2021. Works by the artist will feature in the gallery’s presentation for Frieze London 2020 (9–16 October; previews 7–8 October). An artist of uncompromising vision and a peerless storyteller, Paula Rego has since the 1950s brought immense psychological insight and imaginative power to the genre of figurative art. Drawing upon details of her own extraordinary life, on politics and art history, on literature, folk legends, myths and fairytales, Rego’s work at its heart is an exploration of human relationships, her piercing eye trained on the established order and the codes, structures and dynamics of power that embolden or repress the characters she depicts. Often turning hierarchies on their heads, her tableaux, whether tender or tragic, consider the complexities of human experience and the experience of women in particular. She is especially celebrated for works that forcibly address aspects of female agency and resolve, suffering and survival, such as the Dog Women series, begun in 1994, the Abortion series, 1998–99, which is considered to have influenced Portugal’s successful second referendum on the legalisation of abortion in 2007, and the recent series Female Genital Mutilation, 2008–09. Next year, the largest and most comprehensive retrospective of Rego’s work to date will take place at Tate Britain (16 June–24 October 2021). -

Now Representing Paula Rego's Prints Cristea Roberts Gallery Is Delighted

Cristea Roberts Gallery Press Release 43 Pall Mall, London SW1Y 5JG Press Contact: +44 (0)20 7439 1866 Gemma Colgan [email protected] [email protected] www.cristearoberts.com +44 (0)20 7439 1866 Thursday 1 October 2020 Cristea Roberts Gallery is delighted to announce that it is now the representative for Paula Rego’s prints Over the past sixty years Dame Paula Rego RA (b. 1935) has established herself as one of the most important figurative artists of her generation. Rego explores themes of power, rebellion, sexuality and gender, grief and poverty, often through female paragons. Her work ranges from painting, pastel, and prints to sculptural installations. Prints by Paula Rego will be represented by Cristea Roberts Gallery. Original works by Paula Rego will be represented by Victoria Miro. Cristea Roberts Gallery Director David Cleaton-Roberts comments, “Paula Rego is rightly celebrated as one of the most important and influential artists working today. Her intense and ground-breaking works in painting, drawing and printmaking have consistently challenged the status quo, and we are honoured and delighted to have the opportunity to be able to work with Paula.” Paula Rego in her studio, London, 2019. Photo: Nick Willing Over the course of her career, Rego has produced an important body of prints which the gallery will include in a solo exhibition in Autumn 2021 as well as its ongoing programme of art fairs and catalogue publications, bringing reflect the innovative possibilities of the medium through this vital element of her practice to a wider international her experimentation with etching, lithography and aquatint, audience. -

Casa Das Histórias Paula Rego, Cascais, Portugal

COLORED CONCRETE WORKS ® www.colored-concrete-works.com Case Study Project: Casa das Histórias Paula Rego, Cascais, Portugal The white plaster interior walls create an effective contrast to the With its two adjacent pyramid-shaped towers, the Casa das Histórias Paula Regois an unmistakable landmark. red integrally coloured concrete. Art history in three dimensions. Museum, art and landscape as a coherent entity. The pyramidal shapes of the Casa das Histórias Paula Rego in Cascais, Portugal, on the coast of Estoril, are what make the museum unique in its architecture. The museum pro- vides a most appropriate home for the collection of works by the internationally distin- guished artist Paula Rego, who lived in Estoril for many years. The building was designed in keeping with the artist’s own wishes, and it was Paula Rego herself who selected the archi- tect. The Portuguese architect Eduardo Souto de Moura, considered one of the most promi- nent representatives of the Escola do Porto, designed a structure that meets all the techni- cal and architectural requirements of a museum without sacrificing a friendly atmosphere. Two pyramid-shaped buildings of equal size, made of red concrete coloured with Bayferrox® pigments, are harmoniously integrated in the surrounding landscape. Inside, interconnect- ed rooms are grouped around a higher, central exhibition space. The museum provides 750 m2 of total exhibition space, an auditorium with seating for 200 and a café that opens onto a garden. Integrally coloured concrete providing a harmonious contrast. Red integrally coloured concrete and green vegetation in harmoni- ous contrast. The link between architecture and nature. -

Tate Report 2002–2004

TATE REPORT 2002–2004 Tate Report 2002–2004 Introduction 1 Collection 6 Galleries & Online 227 Exhibitions 245 Learning 291 Business & Funding 295 Publishing & Research 309 People 359 TATE REPORT 2002–2004 1 Introduction Trustees’ Foreword 2 Director’s Introduction 4 TATE REPORT 2002–2004 2 Trustees’ Foreword • Following the opening of Tate Modern and Tate Britain in 2000, Tate has consolidated and built on this unique achieve- ment, presenting the Collection and exhibitions to large and new audiences. As well as adjusting to unprecedented change, we continue to develop and innovate, as a group of four gal- leries linked together within a single organisation. • One exciting area of growth has been Tate Online – tate.org.uk. Now the UK’s most popular art website, it has won two BAFTAs for online content and for innovation over the last two years. In a move that reflects this development, the full Tate Biennial Report is this year published online at tate.org.uk/tatereport. This printed publication presents a summary of a remarkable two years. • A highlight of the last biennium was the launch of the new Tate Boat in May 2003. Shuttling visitors along the Thames between Tate Britain and Tate Modern, it is a reminder of how important connections have been in defining Tate’s success. • Tate is a British institution with an international outlook, and two appointments from Europe – of Vicente Todolí as Director of Tate Modern in April 2003 and of Jan Debbaut as Director of Collection in September 2003 – are enabling us to develop our links abroad, bringing fresh perspectives to our programme. -

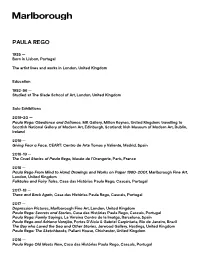

Rego, Paula CV 10 10 19

Marlborough PAULA REGO 1935 — Born in Lisbon, Portugal The artist lives and works in London, United Kingdom Education 1952-56 — Studied at The Slade School of Art, London, United Kingdom Solo Exhibitions 2019-20 — Paula Rego: Obedience and Defiance, MK Gallery, Milton Keynes, United Kingdom; travelling to Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh, Scotland; Irish Museum of Modern Art, Dublin, Ireland 2019 — Giving Fear a Face, CEART: Centro de Arte Tomas y Valiente, Madrid, Spain 2018-19 — The Cruel Stories of Paula Rego, Musée de l’Orangerie, Paris, France 2018 — Paula Rego From Mind to Hand: Drawings and Works on Paper 1980-2001, Marlborough Fine Art, London, United Kingdom Folktales and Fairy Tales, Casa das Histórias Paula Rego, Cascais, Portugal 2017-18 — There and Back Again, Casa das Histórias Paula Rego, Cascais, Portugal 2017 — Depression Pictures, Marlborough Fine Art, London, United Kingdom Paula Rego: Secrets and Stories, Casa das Histórias Paula Rego, Cascais, Portugal Paula Rego: Family Sayings, La Virreina Centre de la Imatge, Barcelona, Spain Paula Rego and Adriana Varejão, Fortes D’Aloia & Gabriel Carpintaria, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil The Boy who Loved the Sea and Other Stories, Jerwood Gallery, Hastings, United Kingdom Paula Rego: The Sketchbooks, Pallant House, Chichester, United Kingdom 2016 — Paula Rego Old Meets New, Casa das Histórias Paula Rego, Cascais, Portugal Marlborough Dancing Ostriches, Marlborough Fine Art, London, United Kingdom Paula Rego Paintings and Etchings from the 1980s, Frieze Masters, United