Street). a Stern Businessman, Sage Had He Fired the Builder, John

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Buckingham Branch Railroad Adds Intermodal Facility in Charlotte

LOCALLY OWNED & OPERATED 75¢ COVERING CHARLOTTE, LUNENBURG & PRINCE EDWARD COUNTIES THE 5 P.O.Southside Box 849, Keysville Va. 23947 July 30-August 5, 2020Messenger Vol. 17, No.6 INSIDE THIS EDITION BELOW THE FOLD Lunenburg Insider Tri County Sports Charlotte County Solar Project Comes Matthews Honored by Public Schools • Reed Signs Contract to a Halt Dixie Softball with LA Chargers The Southside Messenger The Southside Messenger Announcements Lunenburg Insider B Tri-County Sports Charlotte, Lunenburg and Prince Edward Co. Athletic News • Economic Relief Grants THE SOUTHSIDE MESSENGER • July 30-August 5, 2020 THE SOUTHSIDE MESSENGER • July 30-August 5, 2020 B5 & Bus Routes Lunenburg Gets New Assistant Commonwealth’s Attorney VHSL Announces Sports Plan for 2020-21 LUNENBURG - An expe- Clement. “She has a great rienced prosecutor who was work ethic and a wealth of STATEWIDE - The VHSL Contest Date – December 28) benefits of getting our stu- raised in Lunenburg County knowledge of criminal law Executive Committee meeting basketball, gymnastics, dents back to a level of par- is now the Assistant Com- and procedure.” in special session today vot- indoor track, swim/dive, ticipation. The Condensed • COVID-19 Update monwealth’s Attorney there. Spiers graduated from ed (34-1-0) to move forward wrestling Interscholastic Plan leaves Jordan A. Spiers, a 30-year- Virginia Tech with two de- with Model 3 in its re-open- Season 2 (fall) February 15 open the opportunity to play See Pages A5-A7 old former prosecutor in grees, political science and ing of sports and activities – May 1 (First Contest Date – all sports in all three sea- Mecklenburg County, started sociology, in 2012. -

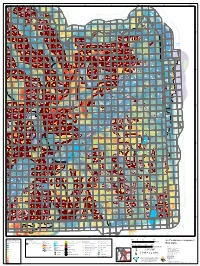

Persistence Component GRSG Persistence Component Towns-Communities ID Roads Hydrology BLM Field Office Admin Boundaries Surface Mgt

114°W 113°30'W 113°W 112°30'W 112°W 111°30'W 111°W 110°30'W R 21 E (ID) R 22 E (ID) R 23 E (ID) R 24 E (ID) R 25 E (ID) R 15 W (MT) R 14 W (MT) R 13 W (MT) R 12 W (MT) R 02 E (MT) R 03 E (MT) 93 Big Dry M Iron/Lime Turner Muleshoe R a Canyon i v d Iron/Lime i e s Creek r o Creek McDevitt n 93 M Creek a ) d H is k o o M L e r M Lee Metcalf n 28 e e s W a a r D e d R m d i i C P e s v i I h Napo Canyon s o e s Poison Creek r r n Earth quake i o n a r t a ( R i n R s r o e i F i e i Lake n v R o v B Wilderness e i e m r 93 C r i l r v k a r r e t e e a e r N v n i S k u t R o 93 s 8 a M E 1 28 Poison Creek 93 LEM HI T Grouse Creek Yearian Creek Cabin Creek r e v Findley i R Basin n o E m l Wade L ake l k R a 93 iv S er k e Cabin e r C Creek 28 Lower Roostercomb n e Reese d y Creek ) 93 a H 29 D Ryegrass/North Hebg en L ake I ( Hayden Freestrip N l n t Cedar Gulch a C ou i g l ar Cr s 7 i t e n e ta k e a k o 93 Roostercomb l i c Cliff Lake r 1 a y l l k ll t M B e o e W v a k re e ra a r s o F o t G e H 29 C F g G N Cabin F r o n u T t e rk a o Little s e M R n Creek e a r D d t n i a 28 Eightmile W so L n i em R n 93 h Snowc i i R rest ve s iv r e r Range 93 Co k ug e H ar e C r e ree C k M n R n r Big Springs e i o y 93 R d s s i a u v e R B n L 29 r o t Hat Creek c a a k i k Wilson C n e re ek s T Hat Creek M e o n ) Mill Creek u d n o R ta y e M d a D Allison i d Mollie Gulch n R i I s o s Creek c o n ( l k tai k 87 R c Little 28 R la B s vi M i v ain e t e Sawmill/South un r e r o d M M N Hayden ic a Walters in Jakes d Leadville e i -

Housing for Seniors in Tompkins County

Housing for Seniors in Tompkins County NY Connects/Tompkins County Office for the Aging 214 W. Martin Luther King Jr./State Street Ithaca, New York 14850 (607) 274-5482 www.tompkinscountyny.gov/cofa Table of Contents A. Independent Living Senior Apartments–(income eligibility; below-market rents) Cayuga Meadows . 3 Center Village Court Apartments.…..……………………...4 Conifer Village......…………………………………………6 Ellis Hollow Apartments..……..………………………..... .7 Fountain Manor ..……………………………...…………...9 Juniper Manor I...…………………………………….... ...10 Juniper Manor II...………………………………………...12 Lehigh Crossing Apartments...…………………………....13 McGraw House...………………………………………….15 Newfield Garden Apartments...…………………………...17 Schoolhouse Gardens Apartments...………………………19 Titus Towers I & II....……………………………………..21 Willowbrook Manor...…………………………………….23 Woodsedge...………………………………………………25 Senior Living Communities (market-rate) Horizon Villages Townhomes.………………………….. 27 Longview Patio Homes..………………………………….28 that include meal, house- Senior Living Communities keeping and other services in base rate. Kendal at Ithaca (life care community)*...……………….29 Longview Apartments..……………………………….….31 Other Independent Living Housing Options Affordable Housing, Section 8, Other Housing Options.....33 B. Licensed Adult Care Residences* (See note about “Enhanced Assisted Living,” and Medicaid Assisted Living Programs (ALPS) on page pp 34-35.) Bridges Cornell Heights.…...…………….……………….35 Brookdale Senior Living...……...………………… ………36 Deer Haven.………………....……………………………38 Kitty Lane.. ………………………………………………38 -

Town of Wawarsing, Village of Ellenville

9 0 2 Y Village of Ellenville A T W E D H R E R E IG I P E A H M J S S HIGHRIDGE RD EA T L N N U MOUNTA IN VIEW LN S E T LL Town of Wawarsing, Village of Ellenville - Election District Boundaries EN R I DG N E RA L N M PK NA E Y Y T D B H I A E LN O S W HEATHER RIDGE RD L C L L D K S I T N L ATE D H L HIGH A A E WAY L U Y 52 G D R D S R O E R O Y L STEAM HOLLOW ROAD I2, J2, K2 E W A L C E C W N A L N P D AR E N P N10 K STEPHENS ROAD J11, K11 F A H L I A Y L E V D L AN L E O L E N9 O IS STEVEN STREET K13, L10, P9 D Street Index 52 W N8 D 209 ¤£ R R C £ O I ¤ D V SUNSET AVENUE F8, G8 E NN OR WI R SYNAGOGUE ROAD L3 NT R D ISH IV T R E E ELLEN RIDGE o OA R AV w TAMARACK ROAD M3, M4, N4 D n S D 42ND STREET J13, J14 FAIRWAY DRIVE K7 NATIONAL STREET M10 O o D T O A f TEL YAFFA LANE L5 A12 A13 A14 A15 W L W A A9 A10 A11 W U A1 A2 A3 A4 A5 A6 A7 A8 T O 44 STREET J13 FIRE TOWER ROAD R11 NESBITT LANE R8 S T M a A A I w R E S S N a TEMPALONI ROAD Q7, R6, R7, S6, S7 N H D U r E I I E M s 5TH AVE A L9 FIRST STREET K11 NEVELE ROAD P8, P9, Q8 N W in M A G D g M IT R R TERRACE DRIVE J14 O9 L T T E 52 IN O V 5TH AVE B K9, L9 FOORDMORE RD J14 NEVINS STREET P9 H C S i B T N T lla IJ O TERRACE STREET I13, J14 R g D L A 5 STAR ROAD M4 FORDEMOOR ROAD K11, K12, K13, K14 NISSENBAUM DRIVE T7 B N V e O A I A 3 C S E o N K T f TERRIE STREET N9 N E ABRAMOWITZ ROAD M5, M6, N5 FOREST HILL S8 NORTH MAIN STREET N9, O9 S M T E P A lle R N S IN n TERWILLIGER ROAD C6, D6 D G R v T S A E i ACADEMY STREET I13, J13 FOX HILL ROAD K11 NORTH SHORE ROAD L7 R V l S T E T le THE -

Township Street Index Meandering Cove

LEGEND Washington Township City of Centerville MONTGOMERY COUNTY OHIO • WASHINGTONTWP.ORG Park District Property A B C D E F G H l. r Surrey Ct. City of T . Stoneybrook Dr. James Hill Rd. Berna Ln. Foxhall Ct. k d Holly Bend e Sandywood Dr. Shambord R Laurelann Dr. e Pl. Locust Dr. Irelan St. Shannon Highgate r Dr. Renwood Dr. Cir. d Shering- Briar Kettering Deerpark Knoll Dr. C Cir. o Far Hills Access Dr. Ct ham Shadyhill Judith Dr. o Ln. Eagleview S Dr. g Pamela u Pepper Hill Dr. Parklawn n w Ct. Foxglen i n Wilmington Pike Walther Rd. n Cir. r Dr. d Walden Way Silverwyck Sue Dr. Mallet Club w a Cir. Ra n n y Foxdale Dr. d i a y Ashwyck Algood Pl. Dr Devonhurst Dr. Presidential Way Pl R Gateway Cir. F Croftshire Dr. W Timberlea Trl. Falling Timber Trl. d NCR . Independence Dr. Cross C . re Ridgeville Ct. Timberwilde Dr Aaron Dr Walnut Walk Bofield Dr. ir e Country Cannonbury Ct C k Hastings Dr. Swigert Rd. n C Cir. e Walden v i Dolley Walther r Club Dr a . City of Rean Meadow Dr. H Georgian Dr. h E Thicket Walk o le Glenheath Dr. r neys ck Ln. i u Hempstead Station Dr. e c Miami Parknoll Rd. Pl. Woodwell Dr. a Bracken Pl. Enid Ave. s Quinn o C Dr Walden Way Marybrook Dr. Kettering Archmore Dr. Valley . t R r Ct . n i L Coker Dr.Marigold r Polen Dr. W School e C Donson Dr. -

Migrant Labor Camps 7-08

Migrant Labor Camp List Ref # 0900 As of Wednesday, July 16, 2008 12:09:46 PM Synopsis Alleghany Roanoke Roanoke County # Occupants Facility Name Address Zip Code # Occupants Valahalla Vineyards 6535 Mt Chestnut Rd Roanoke, Virginia 24018 Total Facility Count For Roanoke County - 1 Total Facility Count For Alleghany Roanoke - 1 Central Campbell County # Occupants Facility Name Address Zip Code # Occupants Barksdale Camp 1185 Mount Calvary Road Brookneal, VA 24528 8 Bass Farms #2 14 Pigeon Run Road Gladys, VA 24554 6 P. M. Fariss-Camp 155 Maddox Road,PO Box 152 Long Island, VA 24569 4 John Mason Farm Camp 2709 Wickcliffe Avenue Brookneal, VA 24528 2 Guthrie Nursery,Inc. Apts.1&3,3 # 66&# 76 Lake Place Lynchburg, VA 24504 12 Winfall Nurseries-Wyatt Elliott Camp 1144 Elliott Rd. Gladys, VA 24554 5 Total Facility Count For Campbell County - 6 37 Appomattox County Facility Name Address Zip Code # Occupants Marston & Son Migrant Labor Camp 8910 Wheelers Spring Road Appomattox, VA 23963 2 Total Facility Count For Appomattox County - 1 2 Amherst County Facility Name Address Zip Code # Occupants Fitzgerald Labor Camp 628 Dillards Hill Road Lowesville, VA 22951 40 Keith Uhl Apples 130 South Amherst Highway Amherst, VA 24521 4 Total Facility Count For Amherst County - 2 44 Total Facility Count For Central - 9 83 Chesterfield Chesterfield # Occupants Facility Name Address Zip Code # Occupants Chesterfield Berry Farm #2 26002 Pear Orchard Road Moseley, Virginia 23120 10 Chesterfield Berry Farm#3 25051 Pear Orchard Road Moseley, Virginia 23120 7 Chesterfield -

Harriman Park Trail

¾¤n Ó Ó NEWYORK Park Office: (845) 947 - 2444 STATE OF Parks, Recreation Mailing Address: OPPORTUNITYTM Regional Office: (845) 786 - 2701 and Historic Preservation HarrimanSeven Lakes Dr / Bear State Mountain Park Circle Palisades Interstate Park Commission Park Police: (845) 786 - 2781 Ramapo, NY 10974 Bear Mountain, NY 10911 In Case of Emergency: 911 e k Legend a L n e Park Office Accessible Parking p lo o p o Parking Cemetery P United State Comfort Station Mine Military Academy Cranberry at West Point Pond Public Campground Scenic View Stillwell NO ENTRY Lake y Group Campground Major Road Bull t [Ç y Pond n t u n o YË Boat Launch Road u Ys C o Lake e C Swimming Area Local Road Frederick g n m a a r n t Shelter Marked Trail (Color Varies) O u ¾¤n )¦ P Gate Unmarked Trail Brooks Lake Trail Brooks AT Zoo Sidewalk Lake Weyants T-T Barnes NO ENTRY Pond Hudson Tower Woods Road !"d$ Lake T-T 77W 79 Highlands LP Twin Train Station Gas Pipeline Lake Forts ¾¤n T-T 1777W 1779 State Park Massawippa Long Path PG Bear Mountain Inn 50' Contour Continues on Turkey Private Property NO ENTRY Hill Pond )¤ Skating Rink Harriman State Park Lake Major Welch Te-Ata LP New York Military PG-TT-1777W-1779 )¤ Major Welch Carousel Other State Park Land Yå Lower Popolopen Gorge Twin Lake Reservation Anthony Wayne Boat Rental Other Public Land Reynolds Road Camp Smith 1779 W PG/ 1779 AT e s NO ENTRY Upper R Queensboro t Summit Twin Lake o c Lake Cornell M ine c h Lake 1777 E k e )¤ s LP la Timp-Torne t n e [ê Yå S-BM d r C C 1777 W 1779 o o !^ u u Cemetery Ski -

Welcome to South Hill Elementary School! We're Glad You're Here

Welcome to South Hill Elementary School! We’re glad you’re here. This booklet will give you some information about our school and our local Ithaca community. Student Support Team Afterschool Programs PTA The Ithaca Community Housing Food Pantries Transportation Learning Resources I’m the South Hill mascot! I’m a hawk. Hi! Go Hawks! Hello! My name is Ms. Jones, SouthI am your Teacher-Librarian.Hill Library The SH library allows families of SH students to check out books. So, not only can your student check out books during the school day, but you can visit the library and select books as well. Call 607-272-3651 for more information. Once a month, the entireSouth school Hillcomes Shinestogether in Assemblyour Gym from 8:00am-8:30am for South Hill Shines. Families are welcome, too! South Hill Shines is a time when students and classrooms put on presentations about what they’ve been learning. Through singing, skits, poems, and other creative ways, the whole school can see what students are working on. Sometimes professional entertainers come, too. For more information, please call 607-274-2129. Southrd th Hill Band & Orchestra Orchestra is available to 3 -5 graders. They can learn viola, violin, cello, and bass. rd th Band is available to 3 -5 graders. They can learn percussion and wind instruments like flute and clarinet. For more information about instruments offered and scholarship opportunities please call Hickey Music at 607-272-8262. Science Olympiad rd th Available to 3 -5 graders, Science Olympiad is a great program. It gives students a challenge and a set of materials to use so they can address the challenge. -

Management Areasberlin Starksboro Buels Gore Fayston Ferrisburg North Half

Duxbury Montpelier CHITTENDEN COUNTY Huntington Moretown 62 Barre City Monkton Management AreasBerlin Starksboro Buels Gore Fayston Ferrisburg North Half Waitsfield Miles Barre Town Pond Brook 0 1.5 3 6 22A Kilometers 0 1.5 3 6 63 Mt. Ellen B e a n Creek 4083' Vergennes ve ldwi Forest Headquarters r a Forest Roads B B r Lincoln Mtn.Cutts Peak o WASHINGTON o Ranger District Office k 3975' 4022' Paved Road Mt. Pleasant COUNTY Town Center 2002' Northfield Gravel Road Little Otter Creek Bald Hill Dirt or Unimproved Road Rice Brook Summit (feet) 1580' 116 ok ro C lay B Ski Area Nancy Hanks Peak FS Summer Trails 291 Panton Bristol 3812' Double Top Mtn. New Haven River 1833' Campground Standard/Terra Trail Lincoln Peak ook Fols m Br 3975' o Burnt Mtn. adow 2733' Waltham e B rook Shelter M r B er o ley FS Winter Trails av o Mt. Abraham Brad New e k H B 4006' Bristol av en Picnic Site Cross-country Ski Trail 17 R Williamstown ive Alder Hill r 1523' Sugarloaf Mtn. Warren 2115' Snowmobile Trail Roxbury Gap Fishing Site Fr 350 Warren ee ma n Lincoln B Interpretive Site New Haven ro ok k South Mtn. Lincoln Broo Observation Site 2325' Lincoln Lincoln Gap M a 349 d Swimming Site R i v e BRISTOL CLIFFS r 66 Trailhead rook ta B Co WILDERNESS Ski Lift s Brook ll 202 i 17 17 Prospect Rock M 402 2016' Electric Transmission Line Mad River k roo etson B Roxbury Addison St State Boundary Chelsea County Boundary 81 25 The Cobble Town Boundary ok 899' o Mt. -

Status of Elementary & Middle Schools

School Accountability Status For The 2007-08 School Year Based On Elementary and Middle School Assessment Results For The 2006-07 School Year Rest of State Schools With Elementary -Middle Grades County/District/School 2007-08 School Year Status Subject County: ALBANY Albany City School District Albany School Of Humanities In Good Standing Arbor Hill Elementary School In Good Standing Delaware Community School In Good Standing Eagle Point Elementary School In Good Standing Giffen Memorial Elementary School In Good Standing Montessori Magnet School In Good Standing North Albany Academy In Good Standing Philip J Schuyler Achievement Academy In Good Standing Philip Livingston Magnet Academy Restructuring - Year 2 Elementary-Middle Level English Language Arts Pine Hills Elementary School In Good Standing School 19 In Good Standing Sheridan Preparatory Academy In Good Standing Stephen And Harriet Myers Middle School In Good Standing Thomas S O'Brien Academy Of Science & T In Good Standing William S Hackett Middle School Restructuring - Year 2 Elementary-Middle Level English Language Arts Berne-Knox-Westerlo Central School District Berne-Knox-Westerlo Elementary School In Good Standing * Berne-Knox-Westerlo Junior-Senior High Sc In Good Standing Bethlehem Central School District Bethlehem Central Middle School In Good Standing Clarksville Elementary School In Good Standing Elsmere Elementary School In Good Standing Glenmont Elementary School In Good Standing Hamagrael Elementary School In Good Standing Slingerlands Elementary School In Good Standing Charter Schools Brighter Choice Charter School For Boys Has No Status - No Title I Funding Brighter Choice School For Girls Has No Status - No Title I Funding Kipp Tech Valley Charter School Has No Status - No Title I Funding *Schools marked with an asterisk (*) serve students in elementary and/or middle as well as high school grades. -

South Hill Rotary Club 1928 - 2011

HISTORY South Hill Rotary Club 1928 - 2011 History of the South Hill Rotary Club 1928 - 2011 The following is a compilation of the history of the South Hill Rotary Club, initially researched and written by Rotarian Frank L. Nanney, Jr. It is not an “all inclusive” history but, rather, a representation of some of the events and programs through the club’s many years of existence. This South Hill Rotary Club His- tory was started in Rotary year 1999 – 2000 under Club President Warren Matthews and continued through 2000 – 2001 under Club President David Frazer. The project, covering the South Hill Clubs History from 1928- 2001, was considered complete at that time. In Rotary Year 2010 – 2011 Club President Randy Cash approached Frank Nanney, the author of the original History, and asked if he would complete the His- tory through July 2011 and the change of leadership to the incoming Club President Judy Jacquelin. Rotarian Frank agreed and began to work on the project. Upon completion the pages were presented to the club and Rotarian Frank indicated that it was almost more work to complete these 10 years than it was to complete the original History to the 73 year mark due to the drastically increased activity by the club. Club President Randy Cash awarded Rotarian Frank the “Above And Beyond Award” for this undertaking. Copies of the finished History were printed by Dogwood Graphics of South Hill and given to the active members of the Club. George D. Radcliffe • CHARTER PRESIDENT — 1928 • South Hill Rotary Club Mr. Radcliffe, a native of England, owned Radcliffe Motor Co. -

South Hill Recreation

SOUTH HILL RECREATION WAY Extension Feasibility Study Written and Edited by Sarah Fiorello and Hector Chang, URS ‘15 with help from aerial imagery and GIS data provided by Chris Hayes, MRP ‘12 New York State GIS Clearinghouse Jeanne Lecesse Tompkins County GIS Division DesignConnect Web Version (Updated 2012-08-22) 2 — THE SOUTH HILL RECREATION WAY — TABLE OF Contents 5 | Executive Summary 6 | Project Scope 8 | Project Support 10 | Anticipated Benefits 11 | Project Challenges 12 | Next Steps 13 | Appendix A: Map of Project Area 16 | Appendix B: 2010 ITCTC Map of Planned and Existing Multi-Use Trails in Tompkins County 19 | Appendix C: 2008 Town Resolutions for the South Hill Recreation Way Extension Project 24 | Appendix D: Preliminary Cost Estimates for the Proposed Town of Caroline Bicycle-Pedestrian Path 27 | Appendix E: 2010 DesignConnect Phone Survey — Extension Feasibility Study | Spring 2012 — 3 LEGEND South Hill Recreation Way (proposed extension) Other multi-use trails (proposed multi-use trails) 4 — THE SOUTH HILL RECREATION WAY — EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Community interest exists to extend the South Hill Recreation Way two miles east from its current termi- nus on Burns Road in the Town of Ithaca to Banks Road in the Town of Caroline. An integral part of the trail network in Tompkins County, the South Hill Recreation Way is a non-motorized, multi-use trail that follows the route of a former railway. The extension would greatly improve the accessibility of the existing trail corridor to residents of the towns of Caroline, Ithaca, Dryden, and Danby. The current scope of this proposed trail project is to extend the South Hill Recreation Way two miles east from its eastern terminus to the intersection of Banks Road in the Town of Caroline.