Sport Corruption Risk Management Strategies”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2018-19 Annual Report

2018-19 ANNUAL REPORT CONTENTS Chairman's Report 2 Remote Projects 16 CEO's Report 3 Michael Long Learning & Leadership Centre 18 Directors 5 Facilities 19 Executive Team & Staff 7 Talent 20 Strategy 9 Commercial & Marketing 22 Community Football 10 Communications & Digital 26 Game Development 14 Financial Report 28 AFLNT 2018-19 Annual Report Ross Coburn CHAIRMAN'S REPORT Welcome to the 2019 AFLNT Annual Report. Thank you to the NT Government for their As Chairman I would like to take this continued belief and support of these opportunity to highlight some of the major games and to the AFL for recognising that items for the year. our game is truly an Australian-wide sport. It has certainly been a mixed year with We continue to grow our game with positive achievements in so many areas with participation growth (up 9%) and have some difficult decisions being made and achieved 100% growth in participants enacted. This in particular relates to the learning and being active in programs discontinuance of the Thunder NEAFL men’s provided through the MLLLC. In times and VFL women’s teams. This has been met when we all understand things are not at with varying opinions on the future their best throughout the Territory it is outcomes and benefits such a decision will pleasing to see that our great game of AFL bring. It is strongly believed that in tune with still ties us altogether with all Territorians the overall AFLNT Strategic Plan pathways, provided with the opportunities to this year's decisions will allow for greater participate in some shape or form. -

ON the TAKE T O N Y J O E L a N D M at H E W T U R N E R

Scandals in sport AN ACCOMPANIMENT TO ON THE TAKE TONY JOEL AND MATHEW TURNER Contemporary Histories Research Group, Deakin University February 2020 he events that enveloped the Victorian Football League (VFL) generally and the Carlton Football Club especially in September 1910 were not unprecedented. Gambling was entrenched in TMelbourne’s sporting landscape and rumours about footballers “playing dead” to fix the results of certain matches had swirled around the city’s ovals, pubs, and back streets for decades. On occasion, firmer allegations had even forced authorities into conducting formal inquiries. The Carlton bribery scandal, then, was not the first or only time when footballers were interrogated by officials from either their club or governing body over corruption charges. It was the most sensational case, however, and not only because of the guilty verdicts and harsh punishments handed down. As our new book On The Take reveals in intricate detail, it was a particularly controversial episode due to such a prominent figure as Carlton’s triple premiership hero Alex “Bongo” Lang being implicated as the scandal’s chief protagonist. Indeed, there is something captivating about scandals involving professional athletes and our fascination is only amplified when champions are embroiled, and long bans are sanctioned. As a by-product of modernity’s cult of celebrity, it is not uncommon for high-profile sportspeople to find themselves exposed by unlawful, immoral, or simply ill-advised behaviour whether it be directly related to their sporting performances or instead concerning their personal lives. Most cases can be categorised as somehow relating to either sex, illegal or criminal activity, violence, various forms of cheating (with drugs/doping so prevalent it can be considered a separate category), prohibited gambling and match-fixing. -

UEFA EURO 2012™ in the Polish Sociopolitical Narration

PHYSICAL CULTURE AND SPORT. STUDIES AND RESEARCH DOI: 10.1515/pcssr-2015-0025 UEFA EURO 2012™ in the Polish Sociopolitical Narration Authors’ contribution: Tomasz Michaluk A-E, Krzysztof Pezdek A-E A) conception and design of the study University School of Physical Education in Wrocław, Poland B) acquisition of data C) analysis and interpretation of data D) manuscript preparation E) obtaining funding ABSTRACT Sport constitutes an increasingly popular language of discourse in modern societies, providing a (formal) system of signs, which is easily used by, among others, businesses, media, public persons, and, particularly willingly, politicians. Thus, sport as a system of meanings can transfer any values, being at the same time a pragmatic way of arguing in the practice of social life. An example we analyze, are the events that took place after Poland (and Ukraine) had been chosen to be host countries of UEFA EURO 2012™, as well as those which took place during the tournament itself. In these analyses, we use the concept of semiotics and, in particular, pragmatism as well as Charles Sanders Peirce’s triadic sign relation. KEYWORDS UEFA EURO 2012, sport, values, semiotics, Peirce Introduction In free and democratic Poland, member of the European Union since 2004, a tournament of the size and importance of the European Championship was organized for the first time in 2012. In April 2007, UEFA 1 chose Poland and Ukraine (non-EU member) as host countries of UEFA EURO 2012™. This measurably influenced a whole body of political, economic, and social processes that took place within the country. After five years of preparation, the tournament took place in June 2012 in sports facilities the majority of which were built or renovated especially for this purpose; and the final match was played in the stadium in Kiev, Ukraine, on 1 July 2012. -

Brisbane Magic Futsal Advisory Panel Les Murray AM

Brisbane Magic Futsal Advisory Panel Les Murray AM Brisbane Magic Futsal is extremely pleased to announce Australia's leading football identity, Mr Les Murray AM as a member our Advisory Panel. Mr Murray began work as a journalist in 1971, changing his name from his native Hungarian for commercial reasons. In between, he found time to perform as a singer in the Rubber Band musical group. He moved to Network Ten as a commentator in 1977, before moving to the multi-cultural network where he made a name for himself - SBS - in 1980. Mr Murray began at SBS as a subtitler in the Hungarian language, but soon turned to covering football. He has been the host for the SBS coverage of football including World Cups since 1986, as well as Australia's World Cup Qualifiers, most memorably in 1997 and 2005. He is a member of Football Federation Australia - Football Hall of Fame as recognition for his contributions to the sport. Mr Murray has been host to several sports programs for SBS over the year, which includes On the Ball (1984 - 2000), The World Game (2001 - present) and Toyota World Sports (1990 - 2006). On June 1, 2006, Murray published his autobiography, By the Balls. Murray was made a Member of the Order of Australia for his services to Association football on June 12, 2006 as part of the Queen's Birthday honours list. In 1996, Murray became SBS's Sports Director, and in 2006, stepped down. He has decided to become an editorial supervisor for SBS instead, while his on-air role remains the same. -

28112003 Cap Mpr 17 D C

OID‰†KOID‰†OID‰†MOID‰†C The Times of India, New Delhi, Friday,November 28, 2003 Phelps-Thorpe no face-off Welcome to Beijing! Chouki vows to fight on US swimmer Michael Phelps will take part in The China Open tennis event will be held French middle-distance runner Fouad 5 events in World Cup shortcourse in Mel- in Beijing in, believe it or not, September Chouki has vowed to take his fight to clear bourne but will not meet Ausssie Ian Thorpe 2004. But the Chinese have already begun his name to the courts after seeing his as both have entered different events. showcasing the event. Thai tennis star doping ban reduced from two years to 18 Phelps is on a $1m incentive to match Mark Paradorn Srichaphan and Russian Marat months plus six months suspended. “I Spitz’s record haul of 7 Olympic golds Safin are the chief promoters am convinced of my innocence,’’ he said Manchester United, Chelsea advance in Champions League ties If the Indians treat the Queensland game like a glorified centre-wicket game, then they are S.O.S. to Dalmiya: Give us Reid as bowling coach nowhere Melbourne: With the Indian cricket spoken to Reid and it is learnt the tall The choice of Reid has brought the Khan and Laxmipathy Balaji on — David Hookes, former team getting a taste of things to come in reed-like fast bowler is not averse to the matter on bowling coach to a complete Wednesday morning about the length Decision on Sunday Australian cricketer the gruelling four-Test series ahead, it idea. -

SBS to Farewell Football Analyst, Craig Foster, After 18 Years with the Network

24 June 2020 SBS to farewell football analyst, Craig Foster, after 18 years with the network SBS today announced that multi award-winning sports broadcaster, Craig Foster, will leave his permanent role at SBS as Chief Football Analyst at the end of July to pursue other challenges. SBS plans to continue working with Craig in the future on the network’s marquee football events. Craig will broadcast FIFA’s decision for hosting rights to the 2023 FIFA Women’s World Cup™ on Friday morning at 8am on SBS, alongside Lucy Zelić, as a fitting farewell to an 18-year career. Craig Foster said: “My deepest gratitude to SBS Chairpersons, Directors, management, colleagues and our loyal viewers across football and news for an incredible journey. SBS provided not just an opportunity, but a mission back in 2002 and I instantly knew that we were aligned in our values, love of football and vision for the game. But the organisational spirit of inclusion, acceptance of diversity and promotion of Australia’s multicultural heart struck me most deeply. We brought this to life through football, but the mission was always to create a better Australia and world. My own challenges lie in this field and I will miss the people, above all, though I will never be too far away. I will always be deeply proud of having called SBS home for so long and look forward to walking down memory lane and thanking everyone personally over the next month.” SBS Managing Director, James Taylor, said: “Craig is one of the finest football analysts and commentators, and has made a significant contribution to SBS over almost two decades. -

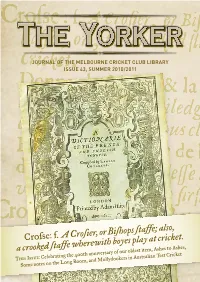

Issue 43: Summer 2010/11

Journal of the Melbourne CriCket Club library issue 43, suMMer 2010/2011 Cro∫se: f. A Cro∫ier, or Bi∫hops ∫taffe; also, a croo~ed ∫taffe wherewith boyes play at cricket. This Issue: Celebrating the 400th anniversary of our oldest item, Ashes to Ashes, Some notes on the Long Room, and Mollydookers in Australian Test Cricket Library News “How do you celebrate a Quadricentennial?” With an exhibition celebrating four centuries of cricket in print The new MCC Library visits MCC Library A range of articles in this edition of The Yorker complement • The famous Ashes obituaries published in Cricket, a weekly cataloguing From December 6, 2010 to February 4, 2010, staff in the MCC the new exhibition commemorating the 400th anniversary of record of the game , and Sporting Times in 1882 and the team has swung Library will be hosting a colleague from our reciprocal club the publication of the oldest book in the MCC Library, Randle verse pasted on to the Darnley Ashes Urn printed in into action. in London, Neil Robinson, research officer at the Marylebone Cotgrave’s Dictionarie of the French and English tongues, published Melbourne Punch in 1883. in London in 1611, the same year as the King James Bible and the This year Cricket Club’s Arts and Library Department. This visit will • The large paper edition of W.G. Grace’s book that he premiere of Shakespeare’s last solo play, The Tempest. has seen a be an important opportunity for both Neil’s professional presented to the Melbourne Cricket Club during his tour in commitment development, as he observes the weekday and event day The Dictionarie is a scarce book, but not especially rare. -

FIFA Council

FIFA Council I. PROCEEDINGS AT THE 68TH FIFA CONGRESS A. INTRODUCTION 1. The 68th FIFA Congress shall review the evaluation report issued by the 2026 Bid Evaluation Task Force in relation to the Bidding Procedure. Based on their best judgement and taking into consideration the defined criteria for the selection decision as set out in the FIFA Regulations for the Selection of the Venue for the Final Competition of the 2026 FIFA World Cup™, the 68th FIFA Congress shall vote on the selection of the host association(s) of the final competition of the 2026 FIFA World Cup™ pursuant to article 69 par. 2 (d) of the FIFA Statutes and based on the decision taken by the 67th FIFA Congress, unless no bid is submitted to the 68th FIFA Congress. In the event that the 68th FIFA Congress decides not to select the host association(s) for the final competition of the 2026 FIFA World Cup™, the second phase of the Bidding Procedure shall be conducted. 2. Proceedings with regard to the relevant agenda item of the 68th FIFA Congress shall be opened by the chair of the Congress. In accordance with art. 5 of the Standing Orders of the Congress, the chair, or a member of the 2026 Bid Evaluation Task Force designated by the FIFA Council, shall give a short report. Such report shall include, in particular, a summary of the results of the evaluation of the bids by the 2026 Bid Evaluation Task Force and an official notification of the FIFA Congress of the bid(s) the FIFA Council has designated for selection. -

Milestones 2008 Milestones

009 2 / Milestones 2008 Milestones Milestones 2008 / 2009 www.lagardere.com Document prepared by the Corporate Communications Department This document is printed on paper from environmentally certified sustainably PEFC/10-31-1222 managed forests. (PEFC/10-31-1222) Grasset 817_MIL09_covHD_c03_T2_UK.indd 2 15/06/09 11:06 à écout res er liv s e 859_MIL09_corpo_T2.indd 1 d 15/06/09 12:03 P r o fi l e Lagardère, a world-class pure-play media group led by Arnaud Lagardère, operates in more than 40 countries and is structured according to four distinct, complementary business lines: • Lagardère Publishing, its book-publishing business segment. • Lagardère Active, which specializes in magazine publishing, audiovisual (radio, television, audiovisual production) and digital activities, and advertising sales. • Lagardère Services, its travel retail and press-distribution business segment. • Lagardère Sports, which specializes in the sports economy and sporting rights. Lagardère holds a 7.5% stake in EADS, over which it exercises joint control. 2 Milestones 2008 / 2009 859_MIL09_corpo_T2.indd 2 15/06/09 12:03 Grasset Pr o fi l e 3 859_MIL09_corpo_T2.indd 3 15/06/09 12:04 GOVERNANCE Arnaud Lagardère editorial I am convinced that we must continually cultivate and strengthen our company fundamentals, which are both straightforward and sound. By giving concrete expression to our strategic perspective as a pure-play media company focusing on content creation, we have achieved unquestioned legitimacy and are now striving for leadership at global level. With the diversifi cation of our activities, both geographically and by business line, we have assembled a well-balanced portfolio of complementary assets. -

CFA Institute Research Challenge Hosted in Local Challenge CFA Society France Report L

CFA Institute Research Challenge Hosted in Local Challenge CFA Society France Report L This report is published for educational purpose only LAGARDÈRE SCA by students competing in the CFA Research Challenge 2016 Euronext Paris 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015E 2016E 2017E 2018E Bloomberg Ticker MMB:FP NET SALES 7657 7370 7216 7170 7017 7429 7721 8015 Type of company: EBITDA 577 541 614 570 538 566 586 613 EBITDA 7.54% 7.34% 8.51% 7.95% 7.66% 7.62% 7.59% 7.65% Conglomerate MARGIN Sector: EBIT 320 302 309 324 324 343 356 370 EBIT MARGIN 4.18% 4.10% 4.28% 4.52% 4.61% 4.61% 4.61% 4.61% Publishing, Media, Travel Retail, NET INCOME -689 106 1319 49 98 121 132 143 Sports & Entertainment Recommendation: HOLD SHARE PRICE: €25.16 Investment Summary TARGET PRICE: €26.97 UPSIDE: +7.19% Recommendation We initiate our coverage of Lagardere SCA with a BUY rating and a target price of € 26.97 which implies a 7.19% potential upside from its current stock price (€25.16). We reckon that, at present, the Market and Stock Data stock is undervalued given its fundamentals. Market Cap 3,299.3 Four Distinct Division, Distinct growth potential The company was created as an SCA (Limited Partnership with Shares) with Jean-Luc Lagardère as Shares 131,133,286 Outstanding Managing Partner. Since 1992 the ecosystem of different companies within Lagardère group (then named Lagardère SCA) changed significantly. As of today, Arnaud Lagardère is the general and 52 weeks price 21.9 - 30.2 managing partner. -

Social Media Events

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2018 Social Media Events Katerina Girginova University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Girginova, Katerina, "Social Media Events" (2018). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 3446. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3446 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3446 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Social Media Events Abstract Audiences are at the heart of every media event. They provide legitimation, revenue and content and yet, very few studies systematically engage with their roles from a communication perspective. This dissertation strives to fill precisely this gap in knowledge by asking how do social media audiences participate in global events? What factors motivate and shape their participation? What cultural differences emerge in content creation and how can we use the perspectives of global audiences to better understand media events and vice versa? To answer these questions, this dissertation takes a social-constructivist perspective and a multiple-method case study approach rooted in discourse analysis. It explores the ways in which global audiences are imagined and invited to participate in media events. Furthermore, it investigates how and why audiences actually make use of that invitation via an analytical framework I elaborate called architectures of participation (O’Reilly, 2004). This dissertation inverts the predominant top-down scholarly gaze upon media events – a genre of perpetual social importance – to present a much needed bottom-up intervention in media events literature. It also provides a more nuanced understanding of what it means to be a member of ‘the audience’ in a social media age, and further advances Dayan and Katz’ (1992) foundational media events theory. -

Fox Sports Presents Live Coverage of Wednesday's

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Claudia Martinez Tuesday, June 12, 2018 [email protected] FOX SPORTS PRESENTS LIVE COVERAGE OF WEDNESDAY’S 2026 FIFA WORLD CUP™ VOTE FIFA Congress Decision Could Return Tournament to the United States for the First Time Since 1994 Moscow – On Wednesday, June 13, FOX Sports, the official English-language broadcaster of the 2018, 2022 and 2026 FIFA World Cups,™ presents coverage of the 68th FIFA Congress on FS1 and the FOX Sports App. FOXSports.com and the FOX Sports App live stream the congress, as voting takes place to determine the host for the 2026 FIFA World Cup™. The Congress begins at 2:00 AM ET, and the vote is expected to take place no earlier than 4:00 AM ET. Beginning at 6:30 AM ET, FS1 offers additional coverage throughout regularly scheduled programming, as the two candidates – Morocco and the United Bid of the United States, Mexico and Canada – await the decision. The special programming is anchored by Rob Stone and features exclusive interviews with the day’s top newsmakers, originating from two locations in Moscow – Expocentre, the location of the FIFA Congress, and FOX Sports’ Red Square studio. Stone is joined by Alexi Lalas in-studio with reports from Grant Wahl from the Expocentre. Coverage continues Wednesday on FS1 at 7:30 PM ET with an hour-long 2018 FIFA WORLD CUP PREVIEW SHOW, with host Stone and studio analysts Lalas, Ian Wright, Guus Hiddink, Lothar Matthäus, Fernando Fiore, Moises Muñoz and Dr. Joe Machnik. On Thursday, June 14, FOX Sports’ kicks off 2018 FIFA World Cup Russia™ coverage at 10:00 AM ET on the FOX broadcast network with WORLD CUP LIVE, followed by the opening match featuring host Russia against Saudi Arabia, and concludes with WORLD CUP TONIGHT at 11:00 PM ET on FOX and FS1.