Use of Nest Boxes by Barrow's Goldeneyes: Nesting Success and Effect on the Breeding Population Author(S): Jean-Pierre L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MOVEMENTS of MARKED SEA and DIVING DUCKS in EUROPE Hugh Boyd

MOVEMENTS OF MARKED SEA AND DIVING DUCKS IN EUROPE Hugh Boyd R inging of dabbling ducks in Europe has helped considerably in discovering the patterns of their distribution and movement through the year. By comparison our knowledge of the behaviour of British species of the tribes Aythyini and Mergini is meagre, chiefly because they are harder to catch outside the breeding season. The numbers marked in Britain have been small, and seem unlikely to be rapidly increased, but ringers in some countries where these ducks breed more plentifully have marked considerably more. Captures of adults, mostly females taken on the nest, have been particularly informative. This paper reviews the results so far apparent. It is based on published and unpublished British records, and on the published material of foreign ringing schemes. I am indebted to the British Trust for Ornithology for permission to use data relating to ducks not ringed at Wildfowl Trust stations. A card index of recoveries compiled by Dr. W. Rydzewski for the International Wildfowl Research Bureau provides a convenient summary of all but the most recent records published abroad, and I am grateful to Dr. Rydzewski and the officers of the Bureau for access to this index. Table I summarises the amount of information obtainable from recoveries and reveals many of its inadequacies. Clearly samples as small as these cannot provide highly reliable and detailed guides to distribution, especially of species which are treated as sporting birds in some countries but not in others. However, by considering the recoveries against the background provided by published studies on the distribution of each species it is possible to form some ideas on the breeding distribution of the populations visiting Britain in winter. -

Review of Seabird Demographic Rates and Density Dependence

JNCC Report No: 552 Review of Seabird Demographic Rates and Density Dependence Catharine Horswill1 & Robert A. Robinson1 February 2015 © JNCC, Peterborough 2015 1British Trust for Ornithology ISSN 0963 8901 For further information please contact: Joint Nature Conservation Committee Monkstone House City Road Peterborough PE1 1JY http://jncc.defra.gov.uk This report should be cited as: Horswill, C. & Robinson R. A. 2015. Review of seabird demographic rates and density dependence. JNCC Report No. 552. Joint Nature Conservation Committee, Peterborough. Review of Seabird Demographic Rates and Density Dependence Summary Constructing realistic population models is the first step towards reliably assessing how infrastructure developments, such as offshore wind farms, impact the population trends of different species. The construction of these models requires the individual demographic processes that influence the size of a population to be well understood. However, it is currently unclear how many UK seabird species have sufficient data to support the development of species-specific models. Density-dependent regulation of demographic rates has been documented in a number of different seabird species. However, the majority of the population models used to assess the potential impacts of wind farms do not consider it. Models that incorporate such effects are more complex, and there is also a lack of clear expectation as to what form such regulation might take. We surveyed the published literature in order to collate available estimates of seabird and sea duck demographic rates. Where sufficient data could not be gathered using UK examples, data from colonies outside of the UK or proxy species are presented. We assessed each estimate’s quality and representativeness. -

Nest Box Guide for Waterfowl Nest Box Guide for Waterfowl Copyright © 2008 Ducks Unlimited Canada ISBN 978-0-9692943-8-2

Nest Box Guide for Waterfowl Nest Box Guide For Waterfowl Copyright © 2008 Ducks Unlimited Canada ISBN 978-0-9692943-8-2 Any reproduction of this present document in any form is illegal without the written authorization of Ducks Unlimited Canada. For additional copies please contact the Edmonton DUC office at (780)489-2002. Published by: Ducks Unlimited Canada www.ducks.ca Acknowledgements Photography provided by : Ducks Unlimited Canada (DUC), Jim Potter (Alberta Conservation Association (ACA)), Darwin Chambers (DUC), Jonathan Thompson (DUC), Lesley Peterson (DUC contractor), Sherry Feser (ACA), Gordon Court ( p 16 photo of Pygmy Owl), Myrna Pearman ,(Ellis Bird Farm), Bryan Shantz and Glen Rowan. Portions of this booklet are based on a Nest Box Factsheet prepared by Jim Potter (ACA) and Lesley Peterson (DUC contractor). Myrna Pearman provided editorial comment. Table of Contents Table of Contents Why Nest Boxes? ......................................................................................................1 Natural Cavities ......................................................................................................................................2 Identifying Wildlife Species That Use Your Nest Boxes .....................................3 Waterfowl ..................................................................................................................4 Common Goldeneye .........................................................................................................................5 Barrow’s Goldeneye -

Alpha Codes for 2168 Bird Species (And 113 Non-Species Taxa) in Accordance with the 62Nd AOU Supplement (2021), Sorted Taxonomically

Four-letter (English Name) and Six-letter (Scientific Name) Alpha Codes for 2168 Bird Species (and 113 Non-Species Taxa) in accordance with the 62nd AOU Supplement (2021), sorted taxonomically Prepared by Peter Pyle and David F. DeSante The Institute for Bird Populations www.birdpop.org ENGLISH NAME 4-LETTER CODE SCIENTIFIC NAME 6-LETTER CODE Highland Tinamou HITI Nothocercus bonapartei NOTBON Great Tinamou GRTI Tinamus major TINMAJ Little Tinamou LITI Crypturellus soui CRYSOU Thicket Tinamou THTI Crypturellus cinnamomeus CRYCIN Slaty-breasted Tinamou SBTI Crypturellus boucardi CRYBOU Choco Tinamou CHTI Crypturellus kerriae CRYKER White-faced Whistling-Duck WFWD Dendrocygna viduata DENVID Black-bellied Whistling-Duck BBWD Dendrocygna autumnalis DENAUT West Indian Whistling-Duck WIWD Dendrocygna arborea DENARB Fulvous Whistling-Duck FUWD Dendrocygna bicolor DENBIC Emperor Goose EMGO Anser canagicus ANSCAN Snow Goose SNGO Anser caerulescens ANSCAE + Lesser Snow Goose White-morph LSGW Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Lesser Snow Goose Intermediate-morph LSGI Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Lesser Snow Goose Blue-morph LSGB Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Greater Snow Goose White-morph GSGW Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Greater Snow Goose Intermediate-morph GSGI Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Greater Snow Goose Blue-morph GSGB Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Snow X Ross's Goose Hybrid SRGH Anser caerulescens x rossii ANSCAR + Snow/Ross's Goose SRGO Anser caerulescens/rossii ANSCRO Ross's Goose -

And Bufflehead (Bucephala Albeola) in Alberta, Canada

Copyright © 2011 by the author(s). Published here under license by the Resilience Alliance. Corrigan, R. M., G. J. Scrimgeour, and C. Paszkowski. 2011. Nest boxes facilitate local-scale conservation of common goldeneye (Bucephala clangula) and bufflehead (Bucephala albeola) in Alberta, Canada. Avian Conservation and Ecology 6(1): 1. http://dx.doi.org/10.5751/ACE-00435-060101 Research Papers Nest Boxes Facilitate Local-Scale Conservation of Common Goldeneye (Bucephala clangula) and Bufflehead (Bucephala albeola) in Alberta, Canada Les nichoirs favorisent la conservation à l’échelle locale du Garrot à œil d’or (Bucephala clangula) et du Petit Garrot (Bucephala albeola) en Alberta, Canada Robert M. Corrigan 1,2, Garry J. Scrimgeour 3, and Cynthia Paszkowski 1 ABSTRACT. We tested the general predictions of increased use of nest boxes and positive trends in local populations of Common Goldeneye (Bucephala clangula) and Bufflehead (Bucephala albeola) following the large-scale provision of nest boxes in a study area of central Alberta over a 16-year period. Nest boxes were rapidly occupied, primarily by Common Goldeneye and Bufflehead, but also by European Starling (Sturnus vulgaris). After 5 years of deployment, occupancy of large boxes by Common Goldeneye was 82% to 90% and occupancy of small boxes by Bufflehead was 37% to 58%. Based on a single-stage cluster design, experimental closure of nest boxes resulted in significant reductions in numbers of broods and brood sizes produced by Common Goldeneye and Bufflehead. Occurrence and densities of Common Goldeneye and Bufflehead increased significantly across years following nest box deployment at the local scale, but not at the larger regional scale. -

Courtship Activities of the Anatidae in Eastern Washington

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Papers in Ornithology Papers in the Biological Sciences 1955 Courtship Activities of the Anatidae in Eastern Washington Paul A. Johnsgard University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciornithology Part of the Ornithology Commons Johnsgard, Paul A., "Courtship Activities of the Anatidae in Eastern Washington" (1955). Papers in Ornithology. 66. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciornithology/66 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Papers in the Biological Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Papers in Ornithology by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Johnsgard in CONDOR (January-February 1955) 57(1). Copyright 1955, University of California and the Cooper Ornithological Society. Used by permission. Jan., 1955 19 COURTSHIP ACTIVITIES OF THE ANATIDAE IN EASTERN WASHINGTON By PAUL A. JOHNSGARD The many interesting and sometimes spectacular aspects of waterfowl courtship have been observed and recordedby several writers. Among the best and most complete descriptionsare those of Bent (1923, 1925), Townsend (1910, 1916), Wetmore (1920), and Hochbaum (1944). However, for the most part these are unillustrated, deal with only a few species, or are based on limited observations. In the summerof 1953 and the spring and summer of 1954 the writer did extensive field work in the Potholes Region of Grant County, Washington, gathering data for an ecological study of the birds and vegetation of that section. In the spring of 1954 he had occasion to observe epigamic activities of most species of waterfowl that are found in that region and was able roughly to delimit the periods of courtship and mating for several species. -

RSPB RESERVES 2009 Black Park Ramna Stacks & Gruney Fetlar Lumbister

RSPB RESERVES 2009 Black Park Ramna Stacks & Gruney Fetlar Lumbister Mousa Loch of Spiggie Sumburgh Head Noup Cliffs North Hill Birsay Moors Trumland The Loons and Loch of Banks Onziebust Mill Dam Marwick Head Brodgar Cottasgarth & Rendall Moss Copinsay Hoy Hobbister Eilean Hoan Loch na Muilne Blar Nam Faoileag Forsinard Flows Priest Island Troup Head Edderton Sands Nigg and Udale Bays Balranald Culbin Sands Loch of Strathbeg Fairy Glen Drimore Farm Loch Ruthven Eileanan Dubha Corrimony Ballinglaggan Abernethy Insh Marshes Fowlsheugh Glenborrodale The Reef Coll Loch of Kinnordy Isle of Tiree Skinflats Tay reedbeds Inversnaid Balnahard and Garrison Farm Vane Farm Oronsay Inner Clyde Fidra Fannyside Smaull Farm Lochwinnoch Inchmickery Loch Gruinart/Ardnave Baron’s Haugh The Oa Horse Island Aird’s Moss Rathlin Ailsa Craig Coquet Island Lough Foyle Ken-Dee Marshes Kirkconnell Merse Wood of Cree Campfield Marsh Larne Lough Islands Mersehead Geltsdale Belfast Lough Lower Lough Erne Islands Portmore Lough Mull of Galloway & Scar Rocks Saltholme Haweswater St Bees Head Aghatirourke Strangford Bay & Sandy Island Hodbarrow Leighton Moss & Morecambe Bay Bempton Cliffs Carlingford Lough Islands Hesketh Out Marsh Fairburn Ings Marshside Read’s Island Blacktoft Sands The Skerries Tetney Marshes Valley Wetlands Dearne Valley – Old Moor and Bolton Ings South Stack Cliffs Conwy Dee Estuary EA/RSPB Beckingham Project Malltraeth Marsh Morfa Dinlle Coombes & Churnet Valleys Migneint Freiston Shore Titchwell Marsh Lake Vyrnwy Frampton Marsh Snettisham Sutton -

Common Goldeneye Bucephala Clangula ILLINOIS RANGE

common goldeneye Bucephala clangula Kingdom: Animalia FEATURES Phylum: Chordata The common goldeneye averages 20 inches in length Class: Aves (tail tip to bill tip in preserved specimen). The male Order: Anseriformes has black feathers on the back and white feathers on the lower body with green head feathers and a Family: Anatidae white facial spot. The female and immature ILLINOIS STATUS goldeneyes have brown head feathers and gray body feathers with a white ring on the neck. Three of the common, native toes are webbed to help with swimming. The bill is flattened and has a toothlike fringe on its edge to ILLINOIS RANGE help strain food from the water. BEHAVIORS The common goldeneye is a common migrant and winter resident in Illinois. This bird is a good diver and may be seen around ponds, sewage lagoons, large rivers and lakes. Its wings produce a whistling sound in flight. The male makes a “pee-ik” sound while the female makes a “quack” sound. Spring migration begins in April. The goldeneye breeds in Canada and the northern United States. Courtship displays may begin as early as January. In the display the male throws his head back and swiftly brings it forward while giving a nasal call. The nest is built in a tree cavity. The female deposits five to 15, green eggs that she alone incubates over the 28-day incubation period. Fall migrants begin arriving in September and do not go much further south than Illinois. The common goldeneye eats small plants and animals found in the water. © Illinois Department of Natural Resources. -

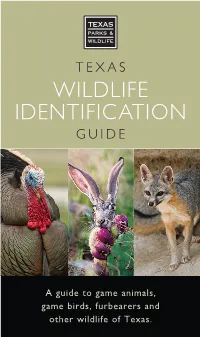

Texas Wildlife Identification Guide

TEXAS WILDLIFE IDENTIFICATION GUIDE A guide to game animals, game birds, furbearers and other wildlife of Texas. INTRODUCTION Texas game animals, game birds, furbearers and other wildlife are important for many reasons. They provide countless hours of viewing and recreational opportunities. They benefit the Texas economy through hunting and “nature tourism” such as birdwatching. Commercial businesses that provide birdseed, dry corn and native landscaping may be devoted solely to attracting many of the animals found in this book. Local hunting and trapping economies, guiding operations and hunting leases have prospered because of the abun- dance of these animals in Texas. The Texas Parks and Wildlife Department benefits because of hunting license sales, but it uses these funds to research, manage and protect all wildlife populations – not just game animals. Game animals provide humans with cultural, social, aesthetic and spiritual pleasures found in wildlife art, taxidermy and historical artifacts. Conservation organiza- tions dedicated to individual species such as quail, turkey and deer, have funded thousands of wildlife projects throughout North America, demonstrating the mystique game animals have on people. Animals referenced in this pocket guide exist because their habitat exists in Texas. Habitat is food, cover, water and space, all suitably arranged. They are part of a vast food chain or web that includes thousands more species of wildlife such as the insects, non-game animals, fish and i rare/endangered species. Active management of wild landscapes is the primary means to continue having abundant populations of wildlife in Texas. Preservation of rare and endangered habitat is one way of saving some species of wildlife such as the migratory whooping crane that makes Texas its home in the winter. -

Barrow's Goldeneyes Feed Mostly on Aquatic Insects and Crustaceans in Inland Waters During

COSEWIC Assessment and Status Report on the Barrow’s Goldeneye Bucephala islandica Eastern Population in Canada SPECIAL CONCERN 2000 COSEWIC status reports are working documents used in assigning the status of wildlife species suspected of being at risk. This report may be cited as follows: Please note: Persons wishing to cite data in the report should refer to the report (and cite the author(s)); persons wishing to cite the COSEWIC status will refer to the assessment (and cite COSEWIC). A production note will be provided if additional information on the status report history is required. COSEWIC. 2000. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Barrow’s Goldeneye Bucephala islandica, Eastern population, in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vii + 65 pp. (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/status/status_e.cfm). Robert, M., R. Benoit and J.-P.L Savard. 2000. COSEWIC status report on the Barrow’s Goldeneye Bucephala islandica in Canada, in COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Barrow’s Goldeneye Bucephala islandica in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. 1-65 pp. For additional copies contact: COSEWIC Secretariat c/o Canadian Wildlife Service Environment Canada Ottawa, ON K1A 0H3 Tel.: (819) 997-4991 / (819) 953-3215 Fax: (819) 994-3684 E-mail: COSEWIC/[email protected] http://www.cosewic.gc.ca Également disponible en français sous le titre Ếvaluation et Rapport de situation du COSEPAC sur le Garrot d’Islande (Bucephala islandica) au Canada. Cover illustration/photo: Barrow’s Goldeneye — photo by Denis Faucher. ©Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, 2011. -

Bucephala Clangula

Bucephala clangula -- (Linnaeus, 1758) ANIMALIA -- CHORDATA -- AVES -- ANSERIFORMES -- ANATIDAE Common names: Common Goldeneye; Goldeneye European Red List Assessment European Red List Status LC -- Least Concern, (IUCN version 3.1) Assessment Information Year published: 2015 Date assessed: 2015-03-31 Assessor(s): BirdLife International Reviewer(s): Symes, A. Compiler(s): Ashpole, J., Burfield, I., Ieronymidou, C., Pople, R., Wheatley, H. & Wright, L. Assessment Rationale European regional assessment: Least Concern (LC) EU27 regional assessment: Least Concern (LC) In Europe this species has an extremely large range, and hence does not approach the thresholds for Vulnerable under the range size criterion (Extent of Occurrence 10% in ten years or three generations, or with a specified population structure). The population trend appears to be stable, and hence the species does not approach the thresholds for Vulnerable under the population trend criterion (30% decline over ten years or three generations). For these reasons the species is evaluated as Least Concern in Europe. Within the EU27 this species has a very large range, and hence does not approach the thresholds for Vulnerable under the range size criterion (Extent of Occurrence 10% in ten years or three generations, or with a specified population structure). Despite the fact that the population trend appears to be decreasing, the decline is not believed to be sufficiently rapid to approach the thresholds for Vulnerable under the population trend criterion (30% decline over ten years or three generations). For these reasons the species is evaluated as Least Concern in the EU27. Occurrence Countries/Territories of Occurrence Native: Albania; Austria; Azerbaijan; Belarus; Belgium; Bosnia and Herzegovina; Bulgaria; Croatia; Czech Republic; Denmark; Faroe Islands (to DK); Estonia; Finland; France; Georgia; Germany; Greece; Hungary; Iceland; Ireland, Rep. -

Barrow's Goldeneye Species Assessment

BARROW’S GOLDENEYE ASSESSMENT February 5, 2002 Amy Meehan Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife Wildlife Division Resource Assessment Section 650 State Street Bangor, Maine 04401 BARROW’S GOLDENEYE ASSESSMENT TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION...........................................................................................................3 NATURAL HISTORY.....................................................................................................4 Description..........................................................................................................4 Distribution..........................................................................................................4 Taxonomy...........................................................................................................5 Habitat and Diet..................................................................................................6 Breeding Biology ................................................................................................7 Territoriality.........................................................................................................8 Survival and Longevity .......................................................................................9 MANAGEMENT ..........................................................................................................10 Regulatory Authority .........................................................................................10 Past and Current Management.........................................................................10