Moliere in Denmark, Then And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

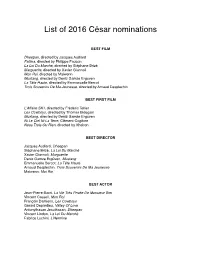

List of Cesar Nominations 2016

List of 2016 César nominations! ! ! ! BEST! FILM! Dheepan, directed by Jacques Audiard! Fatima, directed by Philippe Faucon! La Loi Du Marché, directed by Stéphane Brizé! Marguerite, directed by Xavier Giannoli! Mon Roi, directed by Maiwenn! Mustang, directed by Deniz Gamze Erguven! La Tête Haute, directed by Emmanuelle Bercot! !Trois Souvenirs De Ma Jeunesse, directed by Arnaud Desplechin! ! ! BEST FIRST FILM! L’Affaire SK1, directed by Frédéric Tellier! Les Cowboys, directed by Thomas Bidegain! Mustang, directed by Deniz Gamze Erguven! Ni Le Ciel Ni La Terre, Clément Cogitore! !Nous Trois Ou Rien, directed by Kheiron! ! ! BEST DIRECTOR! Jacques Audiard, Dheepan! Stéphane Brizé, La Loi Du Marché! Xavier Giannoli, Marguerite! Deniz Gamze Ergüven, Mustang! Emmanuelle Bercot, La Tête Haute! Arnaud Desplechin, Trois Souvenirs De Ma Jeunesse! !Maïwenn, Moi Roi! ! ! BEST ACTOR! Jean-Pierre Bacri, La Vie Très Privée De Monsieur Sim! Vincent Cassell, Mon Roi! François Damiens, Les Cowboys! Gérard Depardieu, Valley Of Love! Antonythasan Jesuthasan, Dheepan! Vincent Lindon, La Loi Du Marché! !Fabrice Luchini, L’Hermine! ! ! ! BEST ACTRESS! Loubna Abidar, Much Loved! Emmanuelle Bercot, Mon Roi! Cécile de France, La Belle Saison! Catherine Deneuve, La Tête Haute! Catherine Frot, Marguerite! Isabelle Huppert, Valley Of Love! !Soria Zeroual, Fatima! ! BEST SUPPORTING ACTOR! Michel Fau, Marguerite! Louis Garrel, Mon Roi! Benoit Magimel, La Tête Haute! André Marcon, Marguerite! !Vincent Rottiers, Dheepan! ! ! BEST SUPPORTING ACTRESS! Sara Forestier, -

Le Programme October – November 2017 02 Contents/Highlights

Le Programme October – November 2017 02 Contents/Highlights Ciné Lumière 3–17 Performances & Talks 18–20 Projet Lumière(s) 20 61st BFI London Film Festival Tribute to Jeanne Moreau 25th French Film Festival South Ken Kids Festival 22 5 – 15 Oct 19 Oct – 17 Dec 2 – 9 Nov p.6 pp.16-17 pp.9-13 Kids & Families 23 We Support 24 We Recommend 25 French Courses 27 South Ken Kids Festival Impro! Suzy Storck La Médiathèque / Culturethèque 28 13 – 19 Nov 18 Nov 26 Oct – 18 Nov p.22 p.18 Gate Theatre p.24 General Information 29 front cover image: Redoubtable by Michel Hazanavicius Programme design by dothtm Ciné Lumière New Releases Le Correspondant In Between On Body and Soul FRA/BEL | 2016 | 85 mins | dir. Jean-Michel Ben Soussan, Bar Bahar Teströl és lélekröl with Charles Berling, Sylvie Testud, Jimmy Labeeu, Sophie PSE/ISR/FRA | 2016 | 102 mins | dir. Maysaloun Hamoud, with HUN | 2017 | 116 mins | dir. Ildikó Enyedi, with Géza Mousel | cert. tbc | in French with EN subs Mouna Hawa, Sana Jammelieh, Shaden Kanboura | cert. 15 Morcsányi, Alexandra Borbély, Zoltán Schneider | cert. 18 in Hebrew & Arabic with EN subs in Hungarian with EN subs Malo and Stéphane are two students who are kind of losers and have just started high school. Their genious Winner of the Young Talents Award in the Women in Marking a singular return for Hungarian writer-director plan to become popular: to host a German exchange Motion selection in Cannes this year, In Between follows Ildikó Enyedi after an 18-year gap, On Body and Soul tells student with a lot of style, preferably a hot girl. -

Leonardo Reviews

LEON4004_pp401-413.ps - 6/21/2007 3:40 PM Leonardo Reviews LEONARDO REVIEWS this book’s ability to convey the world- aid the organizational structure in the Editor-in-Chief: Michael Punt wide connectivity that was emerging in effort to present basic themes. These, Managing Editor: Bryony Dalefield the second half of the 20th century. in turn, allow us more easily to place One of the stronger points of the book the recent art history of Argentina, Associate Editor: Robert Pepperell is the way the research translates the Brazil, Mexico, Uruguay, Venezuela, A full selection of reviews is regional trends of the mid-1940s into Croatia, the Czech Republic, Hungary published monthly on the LR web site: an environment that was setting the and Poland in relation to that of the <www.leonardoreviews.mit.edu>. stage for the international art world of West. the 1960s to take form. In effect, the The range of artists is equally local communities gave way to a global impressive. Included are (among vision, due, in part, to inexpensive air others) Josef Albers, Bernd and Hilla BOOKS travel, the proliferation of copying Becher, Max Bill, Lucio Fontana, Eva technologies and the growing ease Hesse, On Kawara, Sol LeWitt, Bruce of linking with others through long Nauman, Hélio Oiticica, Blinky distance telecommunication devices. Palermo, Bridget Riley, Jesus Rafael BEYOND GEOMETRY: Authored by six writers (Lynn Soto, Frank Stella, Jean Tinguely, and XPERIMENTS IN ORM E F , Zelevansky, Ines Katzenstein, Valerie Victor Vasarely. Among the noteworthy 1940S–1970S Hillings, Miklós Peternák, Peter Frank contributions are the sections integrat- edited by Lynn Zelevansky. -

Copenhagen and Norway by Rail and Ferry with Iceland Option

The Traveling Professor Presents COPENHAGEN AND NORWAY BY RAIL AND FERRY WITH ICELAND OPTION TENTATIVE ITINERARY Day 1: Arrival Copenhagen With perhaps the best location in all of Copenhagen, the 4-star waterfront Admiral Hotel is in the heart of the city. Located in the theater district, steps from the Nyhavn Canal, it is near shopping, best attractions, great dining spots. Stroll just outside the hotel to see the Little Mermaid, the stunning Opera house, and the Royal Danish Playhouse. Once everyone is checked in and settled, a relaxing canal tour is planned, usually in late afternoon or early evening. Day 2: Copenhagen So much to see and do - start the first full day with a professionally guided tour of the city. The remainder of the day is on your own with a personal “key to the city” – 24 hours of free public transportation and VIP admission to nearly every attraction in Copenhagen including Tivoli Gardens. In the evening let’s meet for dinner at a spot right on the Nyhavn canal. Day 3: Copenhagen to Oslo After a free morning in Copenhagen, embark on a scenic overnight Commodore-class ferry cruise to Oslo. Each room has a large comfortable bed with sea-view windows. There is a TV, hair dryer, plush linens and towels. Enjoy a room service breakfast or dining room service as we pull into stunning Oslo the next morning. Day 4: Arrival in Oslo After a spectacular arrival into Oslo harbor at about 9:30 a.m., drop our bags at the hotel and hop on the tram through charming neighborhoods to famous Vigelandsparken Sculpture Park. -

Westworld Opens on Foxtel

Media Release: Friday, August 12, 2016 Westworld opens on Visit the ultimate resort from 12pm AEDST Monday, October 3 - same time as the US - only on showcase Westworld, HBO’s highly anticipated reality bending drama, starring Anthony Hopkins, Rachel Evan Wood and James Marsden will arrive on Foxtel on Monday October 3 at 12pm AEDST, same time as the US, with a prime time encore at 8.30pm, only on showcase. Set at the intersection of the near future and the reimagined past, Westworld, based on the 1973 film, is a dark odyssey that looks at the dawn of artificial consciousness and the evolution of sin and explores a world in which every human appetite, no matter how noble or depraved, can be indulged. The 10 episode season of Westworld is an ambitious and highly imaginative drama that elevates the concept of adventure and thrill-seeking to a new, ultimately dangerous level. In the futuristic fantasy park known as Westworld, a group of android “hosts” deviate from their programmers’ carefully planned scripts in a disturbing pattern of aberrant behaviour. Westworld’s cast is led by Anthony Hopkins (Noah, Oscar® winner for The Silence of the Lambs) as Dr. Robert Ford, the founder of Westworld, who has an uncompromising vision for the park and its evolution; Ed Harris (Snowpiercer, Golden Globe winner for HBO’s Game Change; Oscar® nominee for Pollock and Apollo 13) as The Man in Black, the distillation of pure villainy into one man; Evan Rachel Wood (HBO’s Mildred Pierce and True Blood) as Dolores Abernathy, a provincial rancher’s daughter who starts to discover her idyllic existence is an elaborately constructed lie; James Marsden (The D Train, the X-Men films) as Teddy Flood, a new arrival with a close and recurring bond with Dolores; Thandie Newton (Half of a Yellow Sun, Mission: Impossible II) as Maeve Millay, a madam with a knack for survival; and Jeffrey Wright (The Hunger Games films; HBO’s Confirmation and Boardwalk Empire) as Bernard Lowe, the brilliant and quixotic head of Westworld’s programming division. -

National Morgan Horse Show July ?6, 27

he ULY 9 8 MORGAN HORSE NATIONAL MORGAN HORSE SHOW JULY ?6, 27 THE MORGAN HORSE Oldest and Most Highly Esteemed of American Horses MORGAN HORSES are owned the nation over and used in every kind of service where good saddle horses are a must. Each year finds many new owners of Morgans — each owner a great booster who won- ders why he didn't get wise to the best all-purpose saddle horse sooner. Keystone, the champion Morgan stallion owned by the Keystone Ranch, Entiat, Washington, was winner of the stock horse class at Wash- ington State Horse Show. Mabel Owen of Merrylegs Farm wanted to breed and raise hunters and jumpers. She planned on thoroughbreds until she discovered the Morgan could do everything the thoroughbred could do and the Morgan is calmer and more manageable. So the Morgan is her choice. The excellent Morgan stallion, Mickey Finn, owned by the Mar-La •antt Farms, Northville, Michigan, is another consistent winner in Western LITTLE FLY classes. A Morgan Horse on Western Range. Spring Hope, the young Morgan mare owned by Caven-Glo Farm Westmont, Illinois, competed and won many western classes throughout the middle-west shows the past couple of years, leaving the popular Quar- ter horse behind in many instances. The several Morgan horses owned by Frances and Wilma Reichow of Lenore, Idaho, usually win the western classes wherever they show. J. C. Jackson & Sons operate Pleasant View Ranch, Harrison, Mon- tana. Their Morgan stallion, Fleetfield, is a many-times champion in western stock horse classes. They raise and sell many fine Morgan horses each year. -

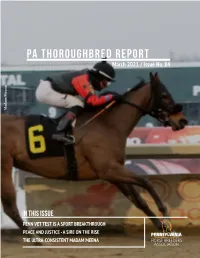

PA THOROUGHBRED REPORT March 2021 / Issue No

PA THOROUGHBRED REPORT March 2021 / Issue No. 84 Madam Meena Madam IN THIS ISSUE PENN VET TEST IS A SPORT BREAKTHROUGH PEACE AND JUSTICE - A SIRE ON THE RISE THE ULTRA-CONSISTENT MADAM MEENA Letter From the Executive Secretary Once again, Governor Wolf has proposed cutting $199 million from the Race Horse Development Trust Fund. Let me begin by saying that this is only a proposal and is very unlikely to gain any traction in the House or the Senate. This same proposal failed to gain any meaningful support last year. This move is illegal and we are confident that the RHDTF will withstand this assault, but we must take every attack on the fund very seriously. I would like to refer you to the following sections of the Trust language: S1405.1 Protection of the Fund – Daily assessments collected or received by the department under section 1405 (relating to the Pennsylvania Race Horse Development Trust Fund) are not funds of the State. S1405.1 – The Commonwealth shall not be rightfully entitled to any money described under this section and sections 1405 and 1406. Our Equine Coalition is made up of Breeder and Horsemen organizations throughout Pennsylvania, both Thoroughbred and Standardbred. We are hard at work with the best lobbying firms in the state to prevent this injustice from happening but we’re going to need your help! If you’re involved in our program and are a resident of PA, please contact your Representative and Senator and tell them your specific story, and if possible, ask others that you may know in our business to share their stories. -

THE COMMITTEE a NORDIC COLLABORATION Is Taking Place

PROGRAMME THE COMMITTEE A NORDIC COLLABORATION is taking place. Three delegates from Sweden, Norway and Finland are gathered in Lapland to decide on an art piece, which is to be placed where the three borders meet geographically. But the committee is in for a surprise. Instead of a sculpture, the commissioned artist presents his idea of a “Nordic Dance”. The delegates are faced with the true challenges of a democratic decision-making process. Is there something they can agree to be a Nordic movement? GUNHILD ENGER is known for her award- winning short films Subtotal , A Simpler Life and Premature . She studied at Edinburgh College of Art, Lillehammer College and the University of Gothenburg. Her graduation film Bargain was nominated for a BAFTA. JENNI TOIVONIEMI ‘s first film, The Date , was screened at multiple festivals, nominated for several awards and won the Short Film Jury Prize in Sundance and the Crystal Bear, Special Mention in Generation 14plus, Berlinale in 2013. KOMMITTÉN SWEDEN/NORWAY/FINLAND 2016 DIRECTORS Gunhild Enger and Jenni Toivoniemi PRODUCER Marie Kjellson CO-PRODUCERS Isak Eymundsson and Elli Toivoniemi SCREENPLAY Gunhild Enger and Jenni Toivoniemi CINEMATOGRAPHY Jarmo Kiuru, Annika Summerson CAST Cecilia Milocco, Tapio Liinoja, Kristin Groven Holmboe, Martin Slaatto, Teemu Aromaa. DURATION 14 min PRODUCED AND SUPPORTED BY Kjellson & Wik, Tuffi Films and Ape&Bjørn in co- production with Film Väst and SVT with financial support by Swedish Film Institute, Norwegian Film Institute, Finnish Film Foundation, AVEK, YLE and NRK. Commissioned by CPH:LAB INT. SALES TBA AVAILABLE WORLDWIDE EXCLUDING Sweden, Norway, Finland FESTIVAL CONTACT Norwegian Film Institute (in Haugesund, Toril Simonsen) 12 PROGRAMME THE DAY WILL COME THE DAY WILL COME IS A “David versus Goliat” story inspired by actual events. -

C:NTACT – Et Integrationsprojekt

Et teatershowroom En analyse af de personlige historier i C:NTACTs forestilling Maveplasker Af Helle Bach Riis Integreret speciale i Dansk og Kultur- og sprogmødestudier, 2008 Institut for Kultur og Identitet, Roskilde Universitetscenter Vejledere: Erik Svendsen og Birgitta Frello Abstract This dissertation comprises an analysis of the play Maveplasker. Maveplasker is a production of the Department of Integration and Education, C:NTACT, at the Betty Nansen Theatre in Copenhagen. C:NTACT’s intention is to use theatre to portray the diversity of the so called “others” in the Danish society. They do so by creating plays with young people from the age 15 to 25 who get on stage and tell their own, personal stories in the form of a coherent play to a live audience. The young people are not professional actors, and partly for this reason C:NTACT uses the term “reality theatre” to describe these productions. This dissertation argues that the Department, C:NTACT, plays an important role in the shaping of these personal stories – from the beginning the department defined what genres the young participants could express their personal stories through – while acknowledging that genres such as hip-hop an street-dance can lead to a somewhat stereotypical and impersonal portrayal of the young participants. With Maveplasker as its focus, this dissertation investigates what representation of “the others” C:NTACT actually ends up producing. The dissertation presents theories of performativity in order to see how identity categories such as “the others” are produced, reproduced but also possibly transformed. It presents theories of performative aesthetics in order to try and place Maveplasker somewhere in between the representative theatre and the performance in order to investigate the play’s potential to transform a generalised conception of “the others”. -

ABOVE the STREET BELOW the WATER ATS Leporello:Druck 02.02.2010 10:38 Uhr Seite 5

ATS_Leporello:Druck 02.02.2010 10:38 Uhr Seite 1 THE MATCH FACTORY presents a NIMBUS FILM production a film by CHARLOTTE SIELING SIDSE BABETT KNUDSEN NICOLAS BRO ANDERS W. BERTHELSEN ELLEN HILLINGSØ ELLEN NYMAN NILS OLE OFTEBRO WORLD SALES The Match Factory GmbH Balthasarstr. 79 – 81 · 50670 Cologne · Germany phone: +49 – (0)221 – 539 709 – 0 · fax: +49 – (0)221 – 539 709 –10 · e-mail: [email protected] www.the–match–factory.com CHARLOTTE SIELING CAST CREW DIRECTOR Anne Sidse Babett Knudsen Director Charlotte Sieling Born 1960. After securing a firm position From 1994 to 1996 Charlotte studied script Ask Nicolas Bro Screenwriters Yaba Holst, Charlotte Sieling as one of Denmark’s finest TV directors writing at the National Film School of Den- Bente Ellen Hillingsø Producer Lars Bredo Rahbek, Bo Ehrhardt Charlotte Sieling’s debut feature Above The mark. Here she met and struck up a colla - Bjørn Anders W. Berthelsen Associate Producer Søren Green Street Below The Water became a box office bo ration with producer student Lars Bredo Charlotte Ellen Nyman Executive Producer Birgitte Hald success during late 2009 and one of the year’s Rahbek resulting in her 1998 debut short film Carl Niels Ole Oftebro Co-Producers Aagot Skjeldal, Helena Danielsson most widely seen Danish language titles in its Tut & Tone as well as her 2009 debut feature. Irina Lea Maria Høyer Stensnæs Director of Photography Jørgen Johansson, DFF home market. Fadi Mohamed-Ali Bakier Editor Mikkel E. G. Nielsen Starting in the late 1990’s, Charlotte esta b li - Gustav Mads Duelund Hansen Sound Designer Mick Raaschou Charlotte graduated as an actress from The shed herself as the most sought-after Danish Composer Thomas Hass Danish National School of Theatre back in TV director. -

Harbin Ve Kopenhag Opera Binalarının İç Ve Dış Mekan Kullanımı Açısından Değerlendirilmesi

Mimarlık ve Yaşam Dergisi Journal of Architecture and Life 4(2), 2019, (257-281) ISSN: 2564-6109 DOI: 10.26835/my.619944 Derleme Makale Harbin ve Kopenhag Opera Binalarının İç ve Dış Mekan Kullanımı Açısından Değerlendirilmesi Evşen YETİM1*, Mustafa KAVRAZ2 Öz Antik Yunan döneminde başlayan tiyatro sanatının Rönesans’ta müzikli oyunlara dönüşmesi ile ortaya çıkan opera sanatı, tarihi süreç boyunca icra edildikleri yapılar açısından kentler ve ülkeler için gücün ve ihtişamın sembolü olmuş, mimari bir imgeye dönüşmüşlerdir. Opera binaları, dünyanın çeşitli ülkelerinden gelen ziyaretçileri ağırlamakta ve bu ziyaretçiler tarafından da mekanın ve sanatın deneyimlendiği simgesel yapılar olarak karşımıza çıkmaktadırlar. Çalışmada, Henning Larsen tarafından tasarlanan ve Danimarka’nın başkenti Kopenhag’ın zengin kültürünü temsil eden Kopenhag Opera Binası ile MAD3 Mimarlık tarafından Çin’in Harbin kentinde tasarlanan Harbin Opera Binası’nın iç ve dış mekan kullanımı açısından değerlendirmesi yapılmıştır. İç mekanlardaki fuaye, opera salonu, sahne alanı, prova odaları, sahne arkası birimleri, ıslak hacimler ve sosyal alanlar; tasarım, yapım tekniği ve malzeme açısından değerlendirilmiştir. Bununla birlikte, çalışmaya konu olan opera binalarının kent ve yakın çevresi ile kurdukları ilişki açısından da değerlendirilmesi yapılmıştır. Anahtar Kelimeler: Opera Binaları, Harbin Opera Binası, Kopenhag Opera Binası Evaluation of Harbin and Copenhagen Opera Buildings in terms of Indoor and Outdoor Use ABSTRACT The art of the opera, which started with the transformation of the art of theater, which began in the ancient Greek period into musical plays in the Renaissance, became a symbol of power and splendor for cities and countries in terms of the structures they were performed during the historical period and turned into an architectural image. -

Linda O' Carroll Memorial Adult Amateur Clinic

CALIFORNIA DRESSAGE SOCIETY AUGUST 2017 V. 23, I 8 PHOTOS BY CHRISTOPHER FRANKE Linda O’ Carroll Memorial Adult Amateur Clinic - North - June 9-11 Having the opportunity to ride with Hilda Gurney Thank you CDS for the 2017 Linda O’Carroll Memorial in the Adult Amateur Clinic series this year was really great! A big CDS Adult Amateur Clinic Series – North with Hilda Gurney. I was thank-you to CDS for sponsoring this educational series for AA’s lucky enough to be chosen from the wait list. and to my East Bay Chapter for selecting me to attend. The first day of the clinic, Hilda worked on basic things with us. I took my Trakehner gelding Tanzartig Ps whom I competed at Keep the reins short, ride with my legs not from my seat, don’t lean I-1 last year. As Hilda did with each horse and rider pair, she honed back. She said I was a very powerful and strong rider, but Ugo didn’t right in with specific instruction to improve our performance. The need that from me. Hilda liked all of my warm-up exercises, and specific exercises she had different pairs use are too numerous to said we had great rhythm and cadence, and our flying changes were outline here, but I particularly liked her comments about warming pretty good. She said that we needed help in learning how to count up our horses as she drew the parallel to the training pyramid and for the threes. Hilda said that I have great feel, and understood what using it as a guide when suppling the horse in warm-up.