A STUDY on Child LABOUR and It's GENDER Dimensions in SUGARCANE Growing in UGANDA

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contract Farming, Smallholders and Commercialization of Agriculture in Uganda: the Case of Sorghum, Sunflower, and Rice Contract Farming Schemes

Center of Evaluation for Global Action Working Paper Series Agriculture for Development Paper No. AfD-0907 Issued in July 2009 Contract Farming, Smallholders and Commercialization of Agriculture in Uganda: The Case of Sorghum, Sunflower, and Rice Contract Farming Schemes. Gabriel Elepu Imelda Nalukenge Makerere University This paper is posted at the eScholarship Repository, University of California. http://repositories.cdlib.org/cega/afd Copyright © 2009 by the author(s). Series Description: The CEGA AfD Working Paper series contains papers presented at the May 2009 Conference on “Agriculture for Development in Sub-Saharan Africa,” sponsored jointly by the African Economic Research Consortium (AERC) and CEGA. Recommended Citation: Elepu, Gabriel and Nalukenge, Imelda. (2009) Contract Farming, Smallholders and Commercialization of Agriculture in Uganda: The Case of Sorghum, Sunflower, and Rice Contract Farming Schemes. CEGA Working Paper Series No. AfD-0907. Center of Evaluation for Global Action. University of California, Berkeley. Contract Farming, Smallholders and Commercialization of Agriculture in Uganda: The Case of Sorghum, Sunflower, and Rice Contract Farming Schemes. Gabriel Elepu1∗ and Imelda Nalukenge2 1Lecturer in the Department of Agricultural Economics and Agribusiness, Makerere University, Kampala. 2Lecturer (Deceased) in the Department of Agricultural Economics and Agribusiness, Makerere University, Kampala. ABSTRACT: Contract farming has expanded in Uganda due to the promotional efforts of various actors: private, public, and/or international aid agencies. While motives for promoting contract farming may vary by actor, it is argued in this study that contract farming is crucial in the commercialization of smallholder agriculture and hence, poverty reduction in Uganda. However, smallholder farmers in Uganda have reportedly experienced some contractual problems when dealing with large agribusiness firms, resulting in them giving up contract farming. -

Download PDF (7.2

109 The *efrence l.simr/E íUganda Gazettej| Published 23rd March, 2007 Price: Shs. 1000 General Notice No. 122 of 2007. CONTENTS Page The Mining Act—Notices 109 THE ADVOCATES ACT. 109 The Advocates Act—Notices ... NOTICE. 110 The Companies Act—Notices ... The Electoral Commission Act—Notices 110-133 APPLICATION FOR A CERTIFICATE OF ELIGIBILITY. 134 Sm ila Security Services Ltd— Notice It is hereby notified that an application has been 134-136 The Trademarks Act—Registration of Applications presented to the Law Council by Nakibuule Madinah who is 136-138 Advertisements stated to be a holder of Bachelor of Laws of Makerere University having been awarded a Degree on the 22nd day SUPPLEMENT of October, 2004 and to have been awarded a Diploma in Legal Practice by the Law Development Centre on the 16th Legal Notice day of June, 2006 for the issue of a Certificate of Eligibility No. 2—The Universities and Other Tertiary Institutions Act for entry of her name on the Roll of Advocates for Uganda. (Publication of Particulars of a Private Tertiary Institution issued with Provisional Licence) (No. 2) Kampala. STELLA NYANDRIA, Notice. 2007. 21st March. 2007. for Acting Secretary, Law Council. General Notice No. 120 of 2007. THE MINING ACT. 2003 General Notice No. 123 of 2007. (The Mining Regulations, 2004) THE ADVOCATES ACT. NOTICE OF GRANT OF AN EXPLORATION LICENCE NOTICE. It is hereby notified that an Exploration Licence, number EL 0166 registered as number 0001168 has been APPLICATION FOR A CERTIFICATE OF ELIGIBILITY. granted in accordance with the provisions of Section 27 and It is hereby notified that an application has been Section 29 to Glory Ministries International Community presented to the Law Council by Ntaro Nyeko Joseph who Foundation (U) Ltd of P.O. -

Contact List for District Health O Cers & District Surveillance Focal Persons

THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA MINISTRY OF HEALTH Contact List for District Health Ocers & District Surveillance Focal Persons THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA MINISTRY OF HEALTH FIRST NAME LAST NAME E-MAIL ADDRESS DISTRICT TITLE MOBILEPHONE Adunia Anne [email protected] ADJUMANI DHO 772992437 Olony Paul [email protected] ADJUMANI DSFP 772878005 Emmanuel Otto [email protected] AGAGO DHO 772380481 Odongkara Christopher [email protected] AGAGO DSFP 782556650 Okello Quinto [email protected] AMOLATAR DHO 772586080 Mundo Okello [email protected] AMOLATAR DSFP 772934056 Sagaki Pasacle [email protected] AMUDAT DHO 772316596 Elimu Simon [email protected] AMUDAT DSFP 752728751 Wala Maggie [email protected] AMURIA DHO 784905657 Olupota Ocom [email protected] AMURIA DSFP 771457875 Odong Patrick [email protected] AMURU DHO 772840732 Okello Milton [email protected] AMURU DSFP 772969499 Emer Mathew [email protected] APAC DHO 772406695 Oceng Francis [email protected] APAC DSFP 772356034 Anguyu Patrick [email protected] ARUA DHO 772696200 Aguakua Anthony [email protected] ARUA DSFP 772198864 Immelda Tumuhairwe [email protected] BUDUDA DHO 772539170 Zelesi Wakubona [email protected] BUDUDA DSFP 782573807 Kiirya Stephen [email protected] BUGIRI DHO 772432918 Magoola Peter [email protected] BUGIRI DSFP 772574808 Peter Muwereza [email protected] BUGWERI DHO 782553147 Umar Mabodhe [email protected] BUGWERI DSFP 775581243 Turyasingura Wycliffe [email protected] BUHWEJU DHO 773098296 Bemera Amon [email protected] -

Vote:517 Kamuli District Quarter2

Local Government Quarterly Performance Report FY 2020/21 Vote:517 Kamuli District Quarter2 Terms and Conditions I hereby submit Quarter 2 performance progress report. This is in accordance with Paragraph 8 of the letter appointing me as an Accounting Officer for Vote:517 Kamuli District for FY 2020/21. I confirm that the information provided in this report represents the actual performance achieved by the Local Government for the period under review. Date: 11/02/2021 cc. The LCV Chairperson (District) / The Mayor (Municipality) 1 Local Government Quarterly Performance Report FY 2020/21 Vote:517 Kamuli District Quarter2 Summary: Overview of Revenues and Expenditures Overall Revenue Performance Ushs Thousands Approved Budget Cumulative Receipts % of Budget Received Locally Raised Revenues 545,891 373,486 68% Discretionary Government 4,425,320 2,335,957 53% Transfers Conditional Government Transfers 38,103,649 18,539,523 49% Other Government Transfers 1,995,208 612,466 31% External Financing 1,314,664 604,003 46% Total Revenues shares 46,384,732 22,465,434 48% Overall Expenditure Performance by Workplan Ushs Thousands Approved Cumulative Cumulative % Budget % Budget % Releases Budget Releases Expenditure Released Spent Spent Administration 5,566,664 2,817,313 2,271,323 51% 41% 81% Finance 500,261 242,532 192,277 48% 38% 79% Statutory Bodies 915,404 477,769 413,546 52% 45% 87% Production and Marketing 1,755,678 882,304 663,561 50% 38% 75% Health 9,769,288 4,987,922 4,043,308 51% 41% 81% Education 22,602,810 10,376,662 8,850,508 46% 39% 85% -

Mgm-Jun08.Pdf

Contents THE FEEDBACK FOR THE MADHVANI FOUNDATION Editor’s Note 2 A dedicated website was part of the launch for the 2008 / 2009 Madhvani Foundation scholarship program. The Pan Floor at Kakira Sugar Works 4 www.madhvanifoundation.com Kakira the Responsible Employer 5 The site registered 137,315 hits in its first three weeks and 3,951 Application ormsF were downloaded. The site also enables graduates who have been sponsored by the Madhvani Foundation to have their CV’s hosted so that potential Recognising the Contribution of Kakira’s Cane Cutters 6 employers can have a look; underpinning the belief of the Foundation that our responsibility doesn’t just end at Mweya & Paraa Attend the SKAL Gala Evening 8 educating less fortunate Ugandans but also to try and give them a helping hand so that they may embark on the journey of life by obtaining employment. Chobe Safari Lodge A Landmark Destination Being Created 9 Below are a selection of some of the feedback received by visitors to the site : Madhvani Foundation 2008/09 Scholarship Scheme 10 Kakira Hospital - Providing a Service to the Community 12 BAGABO RASHID JOSEPH OKELLO EADL New Brand Identity, New Horizons 13 I am glad that you gave us this chance as this is good for us who cannot afford all the tuition at campus and really do not want The Madhvani Foundation is extremely commendable in terms Madhvani Group Exploring Opportunities in India 14 to miss this opportunity. Thank you Madhvani Foundation of its activities and the quantum of contribution to Uganda. I hope others can emulate this most noble act Madhvani Group Invests in Uganda’s Future 15 NSUBUGA BRIAN Group News Pictorial 16 SAM in London Anybody who promotes education is the only person causing Mweya & Paraa Safari Lodges Invests in Human Assets 20 development from the left ventricle of the heart where the force Well done Muljibhai Madhvani Foundation. -

Vote:511 Jinja District Quarter1

Local Government Quarterly Performance Report FY 2018/19 Vote:511 Jinja District Quarter1 Terms and Conditions I hereby submit Quarter 1 performance progress report. This is in accordance with Paragraph 8 of the letter appointing me as an Accounting Officer for Vote:511 Jinja District for FY 2018/19. I confirm that the information provided in this report represents the actual performance achieved by the Local Government for the period under review. Name and Signature: Accounting Officer, Jinja District Date: 30/10/2018 cc. The LCV Chairperson (District) / The Mayor (Municipality) 1 Local Government Quarterly Performance Report FY 2018/19 Vote:511 Jinja District Quarter1 Summary: Overview of Revenues and Expenditures Overall Revenue Performance Ushs Thousands Approved Budget Cumulative Receipts % of Budget Received Locally Raised Revenues 5,039,582 2,983,815 59% Discretionary Government Transfers 4,063,070 1,063,611 26% Conditional Government Transfers 35,757,925 9,198,562 26% Other Government Transfers 2,554,377 432,806 17% Donor Funding 564,000 0 0% Total Revenues shares 47,978,954 13,678,794 29% Overall Expenditure Performance by Workplan Ushs Thousands Approved Cumulative Cumulative % Budget % Budget % Releases Budget Releases Expenditure Released Spent Spent Planning 183,102 22,472 21,722 12% 12% 97% Internal Audit 132,830 32,942 27,502 25% 21% 83% Administration 6,994,221 1,589,106 1,385,807 23% 20% 87% Finance 1,399,200 320,632 310,572 23% 22% 97% Statutory Bodies 995,388 234,790 160,795 24% 16% 68% Production and Marketing 1,435,191 -

Sustaining the Bee Keeping Program at Namasagali College in Kamuli

Sustaining the Bee Keeping Program at Namasagali College in Kamuli, Uganda Brooklyn Snyder1, Blake Lineweaver2, Mika Rugaramna3, and Grace Nabulo4, 1, 2Iowa State University, Ames, Iowa, USA 3, 4Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda Introduction Results Beekeeping, in the Kamuli district of Uganda, is used . Reestablished original hives according to cultural as an agricultural practice so that the people of and educational influencers Kamuli can be supported by not only the monetary . Established a log book for pupils to ensure value that honey as an entrepreneurial product gives productivity but also the sustainable practice in which consuming . Trained pupils to ensure effective habitat honey provides great nutritional and medicinal maintenance benefits. Manipulated surrounding habitat to be more attractive for colonies . The apiary is located within the secondary school Photo 2). Supported top bar hive Photo 3). Supported log hive . Relocated hives to cover a wider range of space at of Namasagali College where the entrepreneurship Namasagali College near plant species conducive club has direct access to be able to practice hands- Methods for colonization on learning skills concerning agriculture, the . Bated unoccupied hives with cow dung ecosystem, and business management . Created a pulley system for the hives . Encourages a diverse, functional habitat for native . Contacted local farmers Conclusions organisms . Trained members of the entrepreneurial club for . Beekeeping provides essential ecosystem benefits effective habitat maintenance for other organisms and the community . Implemented sunflower plots . Honey is an agricultural product that provides . Identified surrounding plant species reliable income . Cleared invasive and unwanted brush . Education is necessary for innovation . Created a log book for pupils . -

UGANDA Report on Workshop Held September 11-13, 2017

Integrating Gender and Nutrition within Agricultural Extension Services UGANDA Report on Workshop held September 11-13, 2017 Report prepared by Siya Aggrey, Amber E. Martin, Fatmata Binta Jalloh and Dr. Kathleen E. Colverson © INGENAES. Workshop Participants, Nile Hotel, Jinja, Uganda This report was produced as part of the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and US Government Feed the Future project “Integrating Gender and Nutrition within Extension and Advisory Services” (INGENAES). Leader with Associates Cooperative Agreement No. AID-OAA-LA-14-00008. www.ingenaes.illinois.edu The report was made possible by the generous support of the American people through USAID. The contents are the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States government. Introduction Integrating Gender within Agricultural Extension and Advisory Services (INGENAES) is funded by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign is the prime awardee, and partners with the University of California, Davis, the University of Florida, and Cultural Practice, LLC. INGENAES is designed to assist partners in Feed the Future countries (www.feedthefuture.gov) to: • Build more robust, gender-responsive, and nutrition-sensitive institutions, projects and programs capable of assessing and responding to the needs of both men and women farmers through extension and advisory services. • Disseminate gender-appropriate and nutrition-enhancing technologies and access to inputs to improve women’s agricultural productivity and enhance household nutrition. • Identify, test efficacy, and scale proven mechanisms for delivering improved extension to women farmers. • Apply effective, nutrition-sensitive, extension approaches and tools for engaging both men and women. -

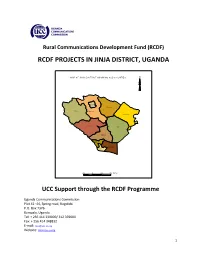

Rcdf Projects in Jinja District, Uganda

Rural Communications Development Fund (RCDF) RCDF PROJECTS IN JINJA DISTRICT, UGANDA MAP O F JINJA DIS TR ICT S HO W ING S UB CO U NTIES N B uw enge T C B uy engo B uta gaya B uw enge Bus ed de B udon do K ak ira Mafubira Mpum udd e/ K im ak a Masese/ Ce ntral wa lukub a Div ision 20 0 20 40 Kms UCC Support through the RCDF Programme Uganda Communications Commission Plot 42 -44, Spring road, Bugolobi P.O. Box 7376 Kampala, Uganda Tel: + 256 414 339000/ 312 339000 Fax: + 256 414 348832 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.ucc.co.ug 1 Table of Contents 1- Foreword……………………………………………………………….……….………..…..…....………3 2- Background…………………………………….………………………..…………..….….……..………4 3- Introduction………………….……………………………………..…….…………….….……….…...4 4- Project profiles……………………………………………………………………….…..…….……....5 5- Stakeholders’ responsibilities………………………………………………….….…........…12 6- Contacts………………..…………………………………………….…………………..…….……….13 List of tables and maps 1- Table showing number of RCDF projects in Jinja district………………l….…….….5 2- Map of Uganda showing Jinja district………..………………….………………....…….14 10- Map of Jinja district showing sub counties………..…………………………………..15 11- Table showing the population of Jinja district by sub counties……………….15 12- List of RCDF Projects in Jinja District…………………………………….………..…..…16 Abbreviations/Acronyms UCC Uganda Communications Commission RCDF Rural Communications Development Fund USF Universal Service Fund MCT Multipurpose Community Tele-centre PPDA Public Procurement and Disposal Act of 2003 POP Internet Points of Presence ICT Information and Communications Technology UA Universal Access MoES Ministry of Education and Sports MoH Ministry of Health DHO District Health Officer CAO Chief Administrative Officer RDC Resident District Commissioner 2 1. Foreword ICTs are a key factor for socio-economic development. -

Participating Outlets and Shops in the Movit Back to School

PARTICIPATING OUTLETS AND SHOPS IN THE MOVIT BACK TO SCHOOL Region Outlets Name Location Urban S/M Buganda Road Future Land Kikuubo Mega Standard SM Aponye Mall Mega Standard S/M Garden City Shoprite S/M Lugogo Best Buy S/M Mengo Save Land S/M Nakulabye Costco S/M Old Kampala Carrefour S/M Oasis Mall Maria & Jesus S/M Kabalagala Shoprite S/M Entebbe Quality S/M Lubowa Pearl S/M Kitooro- Entebbe Divine S/M Kitebi S & S S/M Nkumba Coins Worth S/M Kitala Benco S/M Nyanama Outlet S/M Freedom City Kampala/Entebbe & Mukono C & S S/M Natete Kenjoy S/M Najjankumbi Star S/M Nyanama Gods Plan S/M Makindye Malaika S/M Kasangati Kiseera S/M Kawempe Fraine SM Ntinda Quality S/M Namugongo Zhang Hua S/M Kasangati Cheap Price SM Kamwokya Best Buy S/M Bukoto Jactor 1 S/M Seeta Moon S/M Seeta Sombe S/M Mukono City Shoppers S/M Mukono Siina S/M Mukono One Price Mukono Mid Way Mukono American S/M Clive rd Tata Owen Market st Wall Mart S/M Nizam Kyosiga S/M Kakira New Welcome S/M Main St Jinja Busoga shoppers S/M Aldina D Mart S/M Clive rd Kiira Shoppers S/M Walukuba Jinja Kristian SM Bugembe Nile SM Lubas st A One SM Market st Muzuri S/M Busia Meera Enterprise Busia Busia Shivah S/M Busia Dip Holdings SM Busia Gorasia Kamuli SNG 1 Kamuli SNG 2 Kamuli Kamuli - Buwenge Salon 3 Kamuli Memory shoppers Kamuli Joy sokotor Buwenge Laxi Buwenge Alishbah /London Shoppers Chemungwe Rd Patel SM Kapchorwa Kapchorwa stores Chemungwe Rd Kapchorwa Kapchegwen Mbale rd Jambo Kapchorwa Soti Mbale rd Abrah 1 Bishop Wasikee rd Abrah 2 Bishop Wasike rd Bam Shoppers Naboa rd -

AFRICA - Uganda and East DRC - Basemap ) !( E Nzara Il ILEMI TRIANGLE N N

!( !( !( )"" !( ! Omo AFRICA - Uganda and East DRC - Basemap ) !( e Nzara il ILEMI TRIANGLE N n Banzali Asa Yambio i ! ! !( a t n u ETHIOPIA o !( !( SNNP M Camp 15 WESTERN ( l !( EQUATORIA e !( b e Torit Keyala Lobira Digba J !( !( Nadapal ! l !( ± e r Lainya h a ! !Yakuluku !( Diagbe B Malingindu Bangoie ! !( ! Duru EASTERN ! Chukudum Lokitaung EQUATORIA !( Napopo Ukwa Lokichokio ! ! !( Banda ! Kpelememe SOUTH SUDAN ! Bili Bangadi ! ! Magwi Yei !( Tikadzi ! CENTRAL Ikotos EQUATORIA !( Ango !( Bwendi !( Moli Dakwa ! ! ! Nambili Epi ! ! ! Kumbo Longo !( !Mangombo !Ngilima ! Kajo Keji Magombo !( Kurukwata ! Manzi ! ! Aba Lake Roa !( ! Wando Turkana Uda ! ! Bendele Manziga ! ! ! Djabir Kakuma Apoka !( !( Uele !( MARSABIT Faradje Niangara Gangara Morobo Kapedo !( ! !( !( Dikumba Dramba ! Dingila Bambili Guma ! Moyo !( !( ! Ali !( Dungu ! Wando ! Mokombo Gata Okondo ! ! ! !( Nimule !( Madi-Opel Bandia Amadi !( ! ! Makilimbo Denge Karenga ! ! Laropi !( !( !( LEGEND Mbuma Malengoya Ndoa !( Kalokol ! ! Angodia Mangada ! Duku ile Nimule Kaabong !( ! ! ! ! Kaya N Dembia ert !( Po Kumuka Alb Padibe ! Gubeli ! Tadu Yumbe !( Bambesa ! Wauwa Bumva !( !( Locations Bima !( ! Tapili ! Monietu ! !( ! Dili Lodonga " ! Koboko " Capital city Dingba Bibi Adi !( !( Orom ) ! Midi-midi ! ! !( Bima Ganga Likandi Digili ! Adjumani ! ! ! ! Gabu Todro Namokora Loyoro TURKANA Major city ! Tora Nzoro ! !( !( ! ! !( Lagbo Oleba Kitgum Other city Mabangana Tibo Wamba-moke Okodongwe ! Oria !( !( ! ! ! ! ! Omugo Kitgum-Matidi Kana Omiya Anyima !( ! !( Atiak Agameto Makongo -

Jinja City Constituency: 043 Jinja South Division East

Printed on: Monday, January 18, 2021 19:10:34 PM PRESIDENTIAL ELECTIONS, (Presidential Elections Act, 2005, Section 48) RESULTS TALLY SHEET DISTRICT: 138 JINJA CITY CONSTITUENCY: 043 JINJA SOUTH DIVISION EAST Parish Station Reg. AMURIAT KABULETA KALEMBE KATUMBA KYAGULA MAO MAYAMBA MUGISHA MWESIGYE TUMUKUN YOWERI Valid Invalid Total Voters OBOI KIIZA NANCY JOHN NYI NORBERT LA WILLY MUNTU FRED DE HENRY MUSEVENI Votes Votes Votes PATRICK JOSEPH LINDA SSENTAMU GREGG KAKURUG TIBUHABU ROBERT U RWA KAGUTA Sub-county: 001 JINJA SOUTH DIVISION 001 CENTRAL JINJA 01 ALLIDINA (A-KIR) - GOKHALE 782 14 0 2 1 253 2 0 2 0 0 80 354 10 364 EAST WARD ROAD MAINSTREET PRI.SCH 3.95% 0.00% 0.56% 0.28% 71.47% 0.56% 0.00% 0.56% 0.00% 0.00% 22.60% 2.75% 46.55% COMP. 02 ALLIDINA (KIS-NAKY) - 879 15 1 5 1 279 0 0 1 0 0 92 394 7 401 KUTCH ROAD MAINSTREET 3.81% 0.25% 1.27% 0.25% 70.81% 0.00% 0.00% 0.25% 0.00% 0.00% 23.35% 1.75% 45.62% PRI.SCH COMP. 03 ALLIDINA (NAL-Z) - NIZAM 722 10 0 3 3 250 2 0 1 0 0 99 368 5 373 ROAD MAINSTREET 2.72% 0.00% 0.82% 0.82% 67.93% 0.54% 0.00% 0.27% 0.00% 0.00% 26.90% 1.34% 51.66% PRI.SCH.COMP 04 MAIN STREET EAST PRI. 560 10 0 1 0 182 1 0 0 0 0 59 253 1 254 SCH.