Kenyatta University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spread in Branch Network and Financial Performance of Commercial Banks in Kenya?

SPREAD IN BRANCH NETWORK AND FINANCIAL PERFORMANCE OF COMMERCIAL BANKS IN KENYA SIMEON NYATIKA A RESEARCH PROJECT SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLEMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF MASTER DEGREE OF BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION, SCHOOL OF BUSINESS, UNIVERSITY OF NAIROBI NOVEMBER 2017 i DECLARATION This research project is my original work and has not been submitted for examination in any other university or institution of higher learning for any academic award of credit. Signed …………………………….. Date……………………… SIMEON NYATIKA This research project has been submitted for examination with my approval as the University Supervisor Signed …………………………….. Date……………………… MR. JOAB OOKO Lecturer Department of Finance and Accounting School of Business, University of Nairobi ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I wish to thank a number of individuals and groups who made this project to come true. My sincere appreciation goes to my supervisors, Dr. Nixon Omoro, Mr. Joab Ooko and Dr. Luther Otieno for their guidance and professional advice throughout the research process. Secondly, I wish to thank the School of Business, University of Nairobi for their support and providing me with a conducive environment to pursue this research project. To my parents, Mr. and Mrs. Isaiah Nyatika, thank you for instilling values of discipline and hard work and your encouragement for me to pursue my studies. Last but not least, I want to thank the almighty God for giving me good health during my study period. iii DEDICATION I dedicate this project to my supportive wife, Roselyne Nyamongo who stood by me towards the completion of the research project, my beloved daughter, Joy Monyangi Rioba who is my source of motivation to accomplish my dream. -

Republic of Kenya in the High Court of Kenya at Nairobi

REPUBLIC OF KENYA IN THE HIGH COURT OF KENYA AT NAIROBI MILIMANI LAW COURTS CIVIL DIVISION MISCELLANEOUS APPLICATION NO. 601 OF 2015 IN THE MATTER OF: AN APPLICATION BY THE ASSETS RECOVERY AGENCY FOR ORDERS UNDER SECTIONS 81, 82 AND 87 OF THE PROCEEDS OF CRIME AND ANTI-MONEY LAUNDERING ACT READ WITH ORDER 51 OF THE CIVIL PROCEDURE RULES TO PROHIBIT THE TRANSFER AND OR DISPOSAL OFF OR OTHER DEALINGS (HOWESOEVER DESCRIBED) WITH THE PROPERTY KNOWN AS MAISONETTE HOUSE AT KASARANI LR NO 20857/190, PLOT NUMBER L.R NO RUIRU JUJA EAST BLOCK 2/360, MOTOR VEHICLE TOYOTA PRADO REGISTRATION NUMBER KCD 536P, REGISTRATION NUMBER KCE 874R STATION WAGON TOYOTA PRADO. BETWEEN THE ASSETS RECOVERY AGENCY…………………………APPLICANT AND SAMWEL WACHENJE alias SAM MWADIME ……1ST RESPONDENT SUSAN MKIWA MNDANYI…………………………….2ND RESPONDENT VANDAMME JOHN…………………………….…………3RD RESPONDENT ANTHONY KIHARA GETHI………………….…………4TH RESPONDENT CHARITY WANGUI GETHI………..………….………..5TH RESPONDENT NDUNGU JOHN…………………………………….……..6TH RESPONDENT GACHOKA PAUL …………………………………………7TH RESPONDENT JAMES KISINGO………………………………………..8TH RESPONDENT AND JANE KABURA ………………………INTENDED INTERESTED PARTY NOTICE OF MOTION (Order1 and order 51 Of the Civil procedure Act cap 21,and all other enabling provisions of the law. ) TAKE NOTICE that this honourable court will be moved on the day of 2015 at 9 O’clock in the forenoon or so soon thereafter as the matter may be reached for hearing of an application on the part of Counsel for JANE KABURA the intended Interested Party /applicant herein for ORDERS THAT 1. THAT Jane Kabura be enjoined in these proceedings as an Interested Party . 2. That Jane Kabura do file pleadingsand responses in this matter 3. -

List of the Main Kenyan Financial Institutions That Provide Loans Tothe Agriculutre Sector

LIST OF THE MAIN KENYAN FINANCIAL INSTITUTIONS THAT PROVIDE LOANS TOTHE AGRICULUTRE SECTOR Type of Org Organisation Service for Brief description Website Reference Contact Id Name SHF Zahid Mustafa - Barclays Commercial 1 Barclays is supporting small holder farmers finance. Consumer Banking Limited Bank Director Commercial Julius Ngesa - Head Commercial They have several product to serve farmers. Value Chains supported: dairy, tea and 2 Bank of Africa http://cbagroup.com/ of Business Bank sugar cane (CBA) Development Business Revolving Credit Plan gives you a line of credit which can be paid off over two to five years. Once you have repaid 25% of the loan, you can withdraw funds up to the original limit, without affecting your monthly repayments. The loan can be linked to your business account, so you can transfer funds electronically An Agricultural Production Loan (APL) is a short-term credit that lets you pay for your agricultural input costs. This product is suitable for grain farmers cultivating on either CFC Stanbic Commercial dry land or on an irrigation basis. Loans are provided to individual farmers, groups and http://www.stanbicban Derrick Kimani - 3 Bank Bank legal entities in the agricultural sector, including commercial farmers and agri- k.co.ke/ Digital Channels businesses. Input costs that qualify for production credit include: Seeds and fertilizer; Fuel, oil and lubricants; Herbicides and pesticides; Repairs and maintenance; Crop insurance premiums The vehicle and asset finance packages are designed to support business‚ cash flow and tax requirements. Vehicles and assets we finance include: Tractors; Harvesters; Centre pivots; Solar panels Dairy Asset Finance, value chain finance. -

KDIC Annual Report 2012

Annual Report & Accounts th For Annualthe Year Report ended &3 0Accounts June 20 12 th For the Year ended 30 June 2012 Deposit Protection DepositFund Protection Board i Fund Board i Vision To be a best-practice deposit insurance scheme Mission The Year under Review under Year The Corporate Social Responsibility Social Corporate To promote and contribute to public confidence in the stability of the nation’s 23iii 12 12 financial system by providing a sound safety net for depositors of member institutions. Strategic Objectives • Promote an effective and efficient deposit insurance scheme • Enhance operational efficiency • Promote best practice Strategic Pillars • Strong supervision and regulation • Public confidence • Prompt problem resolutions • Public awareness • Effective coordination Corporate Values • Integrity • Professionalism • Team work • Transparency and accountability • Rule of Law Corporate Information The Year under Review under Year The Corporate Social Responsibility Social Corporate 12iv 23 Deposit Protection Fund Board CBK Pension House Harambee Avenue PO Box 45983 - 00100 Nairobi, Kenya Tel: +254 – 20 - 2861000 , 2863841 Fax: +254 – 20 - 2211122 Email : [email protected] Website: www.centralbank.go.ke Bankers Central Bank of Kenya, Nairobi Haile Selassie Avenue PO Box 60000 - 00200 Nairobi Auditors KPMG Kenya 16th Floor, Lonrho House Standard Street PO Box 40612 - 00100 Nairobi Table of Contents Statement from the Chairman of the Board..................................................................................6 -

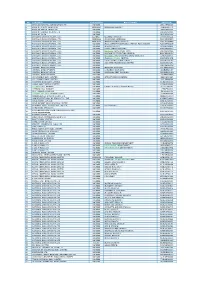

Bank Code Finder

No Institution City Heading Branch Name Swift Code 1 AFRICAN BANKING CORPORATION LTD NAIROBI ABCLKENAXXX 2 BANK OF AFRICA KENYA LTD MOMBASA (MOMBASA BRANCH) AFRIKENX002 3 BANK OF AFRICA KENYA LTD NAIROBI AFRIKENXXXX 4 BANK OF BARODA (KENYA) LTD NAIROBI BARBKENAXXX 5 BANK OF INDIA NAIROBI BKIDKENAXXX 6 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. ELDORET (ELDORET BRANCH) BARCKENXELD 7 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. MOMBASA (DIGO ROAD MOMBASA) BARCKENXMDR 8 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. MOMBASA (NKRUMAH ROAD BRANCH) BARCKENXMNR 9 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. NAIROBI (BACK OFFICE PROCESSING CENTRE, BANK HOUSE) BARCKENXOCB 10 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. NAIROBI (BARCLAYTRUST) BARCKENXBIS 11 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. NAIROBI (CARD CENTRE NAIROBI) BARCKENXNCC 12 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. NAIROBI (DEALERS DEPARTMENT H/O) BARCKENXDLR 13 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. NAIROBI (NAIROBI DISTRIBUTION CENTRE) BARCKENXNDC 14 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. NAIROBI (PAYMENTS AND INTERNATIONAL SERVICES) BARCKENXPIS 15 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. NAIROBI (PLAZA BUSINESS CENTRE) BARCKENXNPB 16 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. NAIROBI (TRADE PROCESSING CENTRE) BARCKENXTPC 17 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. NAIROBI (VOUCHER PROCESSING CENTRE) BARCKENXVPC 18 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. NAIROBI BARCKENXXXX 19 CENTRAL BANK OF KENYA NAIROBI (BANKING DIVISION) CBKEKENXBKG 20 CENTRAL BANK OF KENYA NAIROBI (CURRENCY DIVISION) CBKEKENXCNY 21 CENTRAL BANK OF KENYA NAIROBI (NATIONAL DEBT DIVISION) CBKEKENXNDO 22 CENTRAL BANK OF KENYA NAIROBI CBKEKENXXXX 23 CFC STANBIC BANK LIMITED NAIROBI (STRUCTURED PAYMENTS) SBICKENXSSP 24 CFC STANBIC BANK LIMITED NAIROBI SBICKENXXXX 25 CHARTERHOUSE BANK LIMITED NAIROBI CHBLKENXXXX 26 CHASE BANK (KENYA) LIMITED NAIROBI CKENKENAXXX 27 CITIBANK N.A. NAIROBI NAIROBI (TRADE SERVICES DEPARTMENT) CITIKENATRD 28 CITIBANK N.A. -

Cytonn Report a Product of Cytonn Technologies

Kenya Listed Banks FY'2019 Report, & Cytonn Weekly #16/2020 Focus of the Week Following the release of the FY’2019 results by Kenyan listed banks, the Cytonn Financial Services Research Team undertook an analysis on the financial performance of the listed banks and identified the key factors that shaped the performance of the sector, and our expectations of the banking sector for the rest of the year. The Banking sector witnessed a number of consolidation activities in FY’2019 as players in the sector were either acquired or merged. We still maintain our view that Kenya remains overbanked as the number of banks remains relatively high compared to the population. Increased consolidation will reduce the number of banks in the country which currently stand at 38, thus reducing the commercial banks to population ratio from the current 0.8x. We expect an increase in consolidation activities going forward which will lead to the formation of relatively larger, well-capitalized and possibly more stable entities. As such our report is themed “Increased Consolidation in the Banking Sector” as we assess the key factors that influenced the performance of the banking sector in 2019, the key trends, the challenges banks faced, and areas that will be crucial for growth and stability of the banking sector going forward. As such, we shall address the following: i. Key Themes That Shaped the Banking Sector Performance in FY’2019, ii. Summary of The Performance of the Listed Banking Sector in FY’2019, iii. The Focus Areas of the Banking Sector Players Going Forward, and, iv. -

Commercial Banks Directory As at 30Th April 2006

DIRECTORY OF COMMERCIAL BANKS AND MORTGAGE FINANCE COMPANIES A: COMMERCIAL BANKS African Banking Corporation Ltd. Postal Address: P.O Box 46452-00100, Nairobi Telephone: +254-20- 4263000, 2223922, 22251540/1, 217856/7/8. Fax: +254-20-2222437 Email: [email protected] Website: http://www.abcthebank.com Physical Address: ABC Bank House, Mezzanine Floor, Koinange Street. Date Licensed: 5/1/1984 Peer Group: Small Branches: 10 Bank of Africa Kenya Ltd. Postal Address: P. O. Box 69562-00400 Nairobi Telephone: +254-20- 3275000, 2211175, 3275200 Fax: +254-20-2211477 Email: [email protected] Website: www.boakenya.com Physical Address: Re-Insurance Plaza, Ground Floor, Taifa Rd. Date Licenced: 1980 Peer Group: Medium Branches: 18 Bank of Baroda (K) Ltd. Postal Address: P. O Box 30033 – 00100 Nairobi Telephone: +254-20-2248402/12, 2226416, 2220575, 2227869 Fax: +254-20-316070 Email: [email protected] Website: www.bankofbarodakenya.com Physical Address: Baroda House, Koinange Street Date Licenced: 7/1/1953 Peer Group: Medium Branches: 11 Bank of India Postal Address: P. O. Box 30246 - 00100 Nairobi Telephone: +254-20-2221414 /5 /6 /7, 0734636737, 0720306707 Fax: +254-20-2221417 Email: [email protected] Website: www.bankofindia.com Physical Address: Bank of India Building, Kenyatta Avenue. Date Licenced: 6/5/1953 Peer Group: Medium Branches: 5 1 Barclays Bank of Kenya Ltd. Postal Address: P. O. Box 30120 – 00100, Nairobi Telephone: +254-20- 3267000, 313365/9, 2241264-9, 313405, Fax: +254-20-2213915 Email: [email protected] Website: www.barclayskenya.co.ke Physical Address: Barclays Plaza, Loita Street. Date Licenced: 6/5/1953 Peer Group: Large Branches: 103 , Sales Centers - 12 CFC Stanbic Bank Ltd. -

Download PDF (489.5

NATIONAL COUNCIL FOR LAW REPORTING LIBRARY SPECIAL ISSUE THE KENYA GAZETTE Published by Authority of the Republic of Kenya (Registered as a Newspaper at the G.P.O.) Vol. CXXII — No. 76 NAIROBI, 24th April, 2020 Price Sh. 60 GAZETTE NOTICE NO. 3278 51 percent of the issued share capital of Mayfair Bank Limited by Commercial International Bank (Egypt) S.A.E as per the THE BANKING ACT share subscription agreement dated the 7th November, 2019. (Cap. 488) (c) the shareholders of Commercial International Bank (Egypt) S.A.E vide a resolution passed on the 4th November, 2019 ACQUISITION OF MAYFAIR BANK LIMITED BY COMMERCIAL approved the acquisition of 51 percent of the issued share INTERNATIONAL BANK (EGYPT) S.A.E capital of Mayfair Bank Limited by Commercial International Bank (Egypt) S.A.E as per the share subscription agreement IT IS notified for information of the general public that in exercise dated 7th November, 2019; and of the powers conferred by section 9 (1) and (5) of the Banking Act: (d) the acquisition shall take effect on the 1st May, 2020. (a) the Cabinet Secretary for the National Treasury and Planning, on the 8th April, 2020 approved the acquisition by subscription Dated the 23rd April, 2020. of 51 percent of the issued share capital of Mayfair Bank Limited by Commercial International Bank (Egypt) S.A.E. PATRICK NJOROGE, Governor, Central Bank of Kenya. (b) the shareholders of Mayfair Bank Limited vide a resolution passed on the 25th October, 2019, approved the acquisition of GAZETTE NOTICE NO. 3279 THE CONSTITUTION OF KENYA (Under Article 187) THE INTER—GOVERNMENTAL RELATIONS ACT (No. -

ANNUAL REPORT and Financial Statements

2014 ANNUAL REPORT and Financial Statements Contents1 Board members and committees 2 Senior Management and Management Committees 4 Corporate information 6 Corporate governance statement 8 Director’s report 10 Statement of directors’ responsibilities 11 Report of the independent auditors 12 Statement of profit or loss and other comprehensive income 13 Statement of financial position 14 Statement of changes in equity 15 Statement of cash flows 16 Notes to the financial statements 17 Board Members and Committees 2 Directors Mr. Akif H. Butt Ms. Shiru Mwangi Non Executive Director Non Executive Director Christine Sabwa Mr. Robert Shibutse Non Executive Director Executive Director Mr. Martin Ernest Mr. Abdulali Kurji Non Executive Director Non Executive Director Mr. Sammy A. S. Itemere Ms. Jacqueline Hinga Managing Director Head-Governance & Company Secretary Mr. Dan Ameyo, MBS, OGW - Chairman of the Board Mr. Dan Ameyo serves as the Chairman of Equatorial Commercial Bank Limited. He is a practicing advocate and legal consultant on trade and integration law in Kenya and within the East African Community and COMESA region. Mr. Ameyo serves as Director of Mumias Sugar Company Limited. He is an advocate of the High Court of Kenya, a member of the Law Society of Kenya (LSK) and a Fellow of the Chartered Institute of Arbitrators in London. He served as a State Counsel in the Attorney General’s chambers. He also served as the Post Master General and Chief Executive Officer of Postal Corporation of Kenya. Mr. Ameyo holds a Bachelor of Laws (LL.B) (Hons) Degree from the University of Nairobi and a Master of Laws (LL.M) from Queen Mary, University of London. -

Effect of Electronic Banking on the Operating Costs of Commercial Banks in Kenya

EFFECT OF ELECTRONIC BANKING ON THE OPERATING COSTS OF COMMERCIAL BANKS IN KENYA CATHERINE WANJERI MACHARIA A RESEARCH PROJECT SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF MASTERS OF SCIENCE IN FINANCE, SCHOOL OF BUSINESS, UNIVERSITY OF NAIROBI 2019 DECLARATION This research project is my original work and has not been presented for examination in any other university. Signature……………………………………. Date………………………………… This Research project has been submitted for examination with my approval as university supervisor Signature…………………………………………. Date………………………………… Dr. Mwangi Cyrus Iraya Chairman, Department of Finance and Accounting School of Business ii ACKNOWLEDGMENT I thank the Almighty God for providing the resources required for my project and seeing me through the period. I appreciate the encouragement and moral support given to me by my husband and two children. Many thanks to my Supervisor, Dr. Mwangi Cyrus Iraya for the guidance offered. iii DEDICATION This research is dedicated to my parents for their support and constant push throughout my journey in pursuit of knowledge. They have been a pillar and this would not have been possible without them. iv THE TABLE OF CONTENTS DECLARATION............................................................................................................... ii ACKNOWLEDGMENT ................................................................................................. iii DEDICATION................................................................................................................. -

KDIC Annual Report 2018

ANNUAL REPORT 2017 - 2018 ANNUAL REPORT AND FINANCIAL STATEMENTS FOR THE FINANCIAL YEAR ENDED JUNE 30, 2018 Prepared in accordance with the Accrual Basis of Accounting Method under the International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) CONTENTS Key Entity Information..........................................................................................................1 Directors and statutory information......................................................................................3 Statement from the Board of Directors.................................................................................11 Report of the Chief Executive Officer...................................................................................12 Corporate Governance statement........................................................................................15 Management Discussion and Analysis..................................................................................19 Corporate Social Responsibility...........................................................................................27 Report of the Directors.......................................................................................................29 Statement of Directors' Responsibilities................................................................................30 Independent Auditors' Report.............................................................................................31 Financial Statements: Statement of Profit or Loss and other Comprehensive Income...................................35 -

THE KENYA GAZETTE Published by Authority of the Republic of Kenya (Registered As a Newspaper at the G.P.O.) � Vol

NATIONAL COUNCIL FOR LAW REPORTING LIBRARY THE KENYA GAZETTE Published by Authority of the Republic of Kenya (Registered as a Newspaper at the G.P.O.) Vol. CXXII —No. 78 NAIROBI, 30th April, 2020 Price Sh. 60 CONTENTS GAZETTE NOTICES PAGE PAGE The Land Registration Act—Issue of New Title Deeds 1810,1818 66—The Registered Land (Amendment) Rules, 2020.... 747 The Land Act—Construction of Thwake Multipurpose 67—The Government Lands (Fees) (Amendment) Dam 1810 Rules, 2020 748 The Legal Education Act—Passing of Examinations and 68—The Land Titles (Registration Fees) (Amendment) Pupilage 1811 Rules, 2020 ' 748 The Capital Markets Act 1811-1815 69—The Public APrneurement and Asset Disposal County Governments Notices 1816-1817 Regulations, 2020 749 The Crops Act—Proposed Grant of Tea Licences 1817 70 — The Public Order (State Curfew) (Extension) The Co-operatives Societies Act—Appointment of Order, 2020 869 Liquidator 1817 75—The Kenya Defence Forces (South Africa Visiting Disposal of Uncollected Goods 1818 Forces) Order, 2020 877 Change of Names 1818 SUPPLEMENT No. 55 SUPPLEMENT Nos. 44 and 45 Senate Bills, 2020 National Assembly Bills , 2020 PAGE PAGE The Pandemic Response and Management Bill, 2020 71 The Supplementary Appropriation Bill, 2020 211 The County Allocation of Revenue Bill, 2020 89 SUPPLEMENT Nos. 56 and 57 SUPPLEMENT Nos. 52,53,54,55,56 and 59 Acts, 2020 Legislative Supplements, 2020 PAGE LEGAL NOTICE No. PAGE The Tax Laws (Amendment) Act, 2020 13 65 — The Registration of Titles (Fees) (Amendment) Rules, 2020 747 The Division of Revenue Act, 2020 31 [1809 1810 THE KENYA GAZETTE 30th April, 2020 CORRIGENDA GAZETTE NOTICE NO.